People power

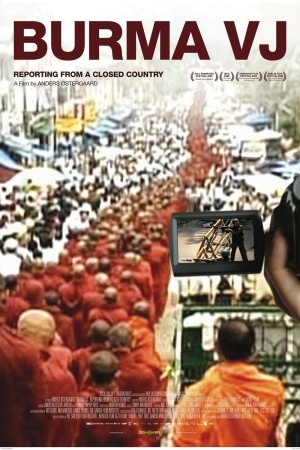

Given an invisible theatrical release in the summer of 2009, and then seemingly disappeared into whatever ether awaits HBO Documentary Films acquisitions before they get around to airing on HBO, the Danish documentary Burma VJ: Reporting from a Closed Country absolutely deserves better than its fate. Not that a film about Burmese monks organising a protest against the military junta controlling their country, as filmed by a small clutch of underground guerrilla videographers would ever be a blockbuster film in these United States, even given the exaggeratedly lowered expectations of documentary box office returns, but it would be nice to think that there was at least some hint of an effort to get this film in a place where people could see it (it has been screened and will continue to be screened at a huge number of documentary festivals in countries across the world, but I mean: who the hell goes to documentary festivals? Apologies in advance to those readers who regularly attend documentary festivals; I would probably be a much happier and smarter man if I joined you). If the film maybe suffers a bit from being too aware of its own significance, and if it is rather more interesting as a social and political document than a cinematic one, well, politics and society can be important, too.

The facts in the case are these: since 1962, Burma has been ruled by a socialist totalitarian military regime. Only once has there been a serious possibility that this regime might be unseated: in 1988, a series of protests and demonstrations that catapulted 43-year-old Aung San Suu Kyi and her opposition party, the National League for Democracy, to national prominence. Her popularity in those days led to the government putting her under house arrest in 1989 - a sentence that remains in place to this day - and to the NLD winning huge majorities in the 1990 election, although virtually all of these results (including Suu Kyi's election to Prime Minister) were simply ignored.

And so for years and years, life in Burma remained as it had always been: one of the most miserably despotic place on Earth, and one of the poorest. The story of Burma VJ begins on 15 August, 2007, when the government lifted fuel subsidies and sent oil and gas prices in the country skyrocketing - in some places, costs doubled in the span of one day. That in turn led to an almost immediate increase in the cost of basic survival, and this triggered a wave of bitter anti-government demonstrations throughout the end of the month, demonstrations that were cracked down upon hard.

In mid-September, the country's large population of Buddhist monks got in on the protest game, marching in the cities and towns of Burma as one. This gesture emboldened many laymen to join in, resulting in a wave of tens of thousands of protesters in Rangoon that was the largest single anti-government demonstration in Burma since 1988; and it was enough to bring the official fist down, despite fears at the start of the monks' protests that it would be politically dangerous for the government to quash their activities. By the end of September, the demonstrations had been all but snuffed out, and so we are, once again, with a Burma that is wretchedly dictatorial and wretchedly poor.

There is but one other fact to consider, and that is the Democratic Voice of Burma, a radio and satellite television organisation based in Norway and made up of Burmese expatriates; the mission of the DVB is to provide information to the citizens of Burma that is free of government control. The junta, naturally, has no love for the DVB, and even before the September, 2007 protests, it had become something of a free ticket to jail to be seen wandering about on the streets pointing a video camera at anything resembling government brutality.

Having puked out all of that context, it becomes a simple matter for me to explain what Burma VJ actually is: Danish filmmaker Anders Østergaard oversaw the assembly of some 80 minutes of footage shot by undercover DVB reporters in August and September of 2007, filmed some dramatic re-enactments of the DVB headquarters in that period with the full input and co-operation of those present at the time, and had the whole thing narrated by "Joshua", a Burmese man in his late 20s who was at the time the head of a team of some 30 Handicam-wielding undercover reporters. The result is an inelegant but forceful and tremendously informative look at a great many different subjects: the revolution, its causes, and its aftermath, naturally; but also the way that the DVB functions, and the sickening danger faced every moment by the undercover reporters who could end up in jail at any moment for doing a good day's work - and indeed, by the end of the protests, that is exactly what happened to most of them, and that is why the content Burma VJ does not actually extend to the end of the events it depicts. The content providers had been imprisoned. That's a weird feeling when it occurs to you, late in the movie.

As a political object, then, there's a whole lot to love about Burma VJ, not least the fiery-eyed tribute it pays to individuals of exceptional bravery and fortitude who literally risk their freedom and their lives to make sure that the rest of the world could see what was going on behind the total blackout imposed by the Burmese government: if you saw anything about the protests on television or the internet back in 2007, it's a dead certainty that you saw footage captured by DVB operatives.

Now, we can probably point out some flaws in the film as a work of art, if that is our aim: obviously it's one-sided, although I hope that it doesn't need my explaining why dictatorial military regimes don't really need fair and balanced documentaries. More to the point, Burma VJ certainly lacks for context; while Østergaard and his editors have assembled the footage into a smooth, quick-moving feature, they leave a great deal of information to be picked up on the fly, and plenty of context simply isn't found within the limits of the film whatsoever. What we see is not elegantly captured nor assembled with the thematic grace of a found-footage documentary in the vein of Grizzly Man, for example: it presents footage of an event, and explains how that footage came to be, and Joshua's level, calm narration provides the rudiments of a story around it. There are no histrionics on display, but there is a great deal of urgency, for even as Joshua clearly places events in the past tense, so does he also leave no doubt that his mission is an ongoing one.

Aesthetic considerations be damned, and thematic, messagey ones too, because Burma VJ isn't a summing-up, but an introduction to a discussion. Its chief function is to explain that the DVB exists, show that organisation's work, and rile up the viewer to follow-up on his or her own initiative. For myself, I have read more about the country's contemporary history in the 24 hours since I saw the film than I had in all my life previously. If that's not testament to its importance and power, then so be it.

9/10

The facts in the case are these: since 1962, Burma has been ruled by a socialist totalitarian military regime. Only once has there been a serious possibility that this regime might be unseated: in 1988, a series of protests and demonstrations that catapulted 43-year-old Aung San Suu Kyi and her opposition party, the National League for Democracy, to national prominence. Her popularity in those days led to the government putting her under house arrest in 1989 - a sentence that remains in place to this day - and to the NLD winning huge majorities in the 1990 election, although virtually all of these results (including Suu Kyi's election to Prime Minister) were simply ignored.

And so for years and years, life in Burma remained as it had always been: one of the most miserably despotic place on Earth, and one of the poorest. The story of Burma VJ begins on 15 August, 2007, when the government lifted fuel subsidies and sent oil and gas prices in the country skyrocketing - in some places, costs doubled in the span of one day. That in turn led to an almost immediate increase in the cost of basic survival, and this triggered a wave of bitter anti-government demonstrations throughout the end of the month, demonstrations that were cracked down upon hard.

In mid-September, the country's large population of Buddhist monks got in on the protest game, marching in the cities and towns of Burma as one. This gesture emboldened many laymen to join in, resulting in a wave of tens of thousands of protesters in Rangoon that was the largest single anti-government demonstration in Burma since 1988; and it was enough to bring the official fist down, despite fears at the start of the monks' protests that it would be politically dangerous for the government to quash their activities. By the end of September, the demonstrations had been all but snuffed out, and so we are, once again, with a Burma that is wretchedly dictatorial and wretchedly poor.

There is but one other fact to consider, and that is the Democratic Voice of Burma, a radio and satellite television organisation based in Norway and made up of Burmese expatriates; the mission of the DVB is to provide information to the citizens of Burma that is free of government control. The junta, naturally, has no love for the DVB, and even before the September, 2007 protests, it had become something of a free ticket to jail to be seen wandering about on the streets pointing a video camera at anything resembling government brutality.

Having puked out all of that context, it becomes a simple matter for me to explain what Burma VJ actually is: Danish filmmaker Anders Østergaard oversaw the assembly of some 80 minutes of footage shot by undercover DVB reporters in August and September of 2007, filmed some dramatic re-enactments of the DVB headquarters in that period with the full input and co-operation of those present at the time, and had the whole thing narrated by "Joshua", a Burmese man in his late 20s who was at the time the head of a team of some 30 Handicam-wielding undercover reporters. The result is an inelegant but forceful and tremendously informative look at a great many different subjects: the revolution, its causes, and its aftermath, naturally; but also the way that the DVB functions, and the sickening danger faced every moment by the undercover reporters who could end up in jail at any moment for doing a good day's work - and indeed, by the end of the protests, that is exactly what happened to most of them, and that is why the content Burma VJ does not actually extend to the end of the events it depicts. The content providers had been imprisoned. That's a weird feeling when it occurs to you, late in the movie.

As a political object, then, there's a whole lot to love about Burma VJ, not least the fiery-eyed tribute it pays to individuals of exceptional bravery and fortitude who literally risk their freedom and their lives to make sure that the rest of the world could see what was going on behind the total blackout imposed by the Burmese government: if you saw anything about the protests on television or the internet back in 2007, it's a dead certainty that you saw footage captured by DVB operatives.

Now, we can probably point out some flaws in the film as a work of art, if that is our aim: obviously it's one-sided, although I hope that it doesn't need my explaining why dictatorial military regimes don't really need fair and balanced documentaries. More to the point, Burma VJ certainly lacks for context; while Østergaard and his editors have assembled the footage into a smooth, quick-moving feature, they leave a great deal of information to be picked up on the fly, and plenty of context simply isn't found within the limits of the film whatsoever. What we see is not elegantly captured nor assembled with the thematic grace of a found-footage documentary in the vein of Grizzly Man, for example: it presents footage of an event, and explains how that footage came to be, and Joshua's level, calm narration provides the rudiments of a story around it. There are no histrionics on display, but there is a great deal of urgency, for even as Joshua clearly places events in the past tense, so does he also leave no doubt that his mission is an ongoing one.

Aesthetic considerations be damned, and thematic, messagey ones too, because Burma VJ isn't a summing-up, but an introduction to a discussion. Its chief function is to explain that the DVB exists, show that organisation's work, and rile up the viewer to follow-up on his or her own initiative. For myself, I have read more about the country's contemporary history in the 24 hours since I saw the film than I had in all my life previously. If that's not testament to its importance and power, then so be it.

9/10