Disney Animation: Family means nobody gets left behind, or forgotten

Of all the stories of Disney Feature Animation in the '00s, one of the saddest to me is the fate of Chris Sanders - all the sadder because it is lacks drama or operatic tragedy, but is just a little example of the meanness and pettiness of corporate filmmaking.

Sanders was a character designer on a number of 1980s cartoon series, when he was first hired by the Walt Disney Company to work on The Rescuers Down Under. From here he was quickly moved to the story department, helping to develop a handful of projects from Beauty and the Beast to Mulan, and in the process establishing himself as one of the great talents at Disney, if one whose contributions went unsung (for even among animation buffs, storymen are only very rarely accorded any degree of fame or fandom.

It was after the completion of Mulan that he was given his big break in the company. Many, many years earlier, even before he'd joined up with Disney, Sanders had created a little alien with a big mouthful of teeth and a propensity for causing massive amounts of destruction wherever he want, named "Stitch". He'd never been able to sell anyone on the character, though, and his sketches lay in the dark for many years, waiting for the right moment. That moment came when Michael Eisner concluded that, after the middling box-office returns of the highly prestigious and costly Pocahontas and The Hunchback of Notre Dame, the studio needed to make something on the cheap, something simple and straightforward and absolutely family-friendly: a little kid's cartoon, essentially, reminiscent of how after the the massive expenses of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, and Fantasia, the company had followed with its all-time cheapest feature, the delicate little fable Dumbo (there are other reasons why that feature is an important touchstone at this point, and I will get to them soon enough). Sanders's Stitch project, which at the time involved the character as an intergalactic con-man in flight from justice ending up befriending a little girl in Kansas, got the green-light, I suppose in recognition of that man's significant contributions to the company over the years; it was going to be the second feature produced entirely at the Florida arm of the studios, following Mulan.

While the executives fussed and bothered over the extraordinarily costly Tarzan and Treasure Planet, the game-changing adventure film Atlantis: The Lost Empire, and the nightmare happening with Kingdom of the Sun/The Emperor's New Groove, Chris Sanders and his co-creator Dean DeBlois (the two had previously led the writing of Mulan, after DeBlois arrived at Disney from the disintegration of Don Bluth Productions in the mid-1990s) were able to work with a stunning lack of corporate oversight, being permitted to make their movie essentially as they thought best. Along the way, the action was switched to the Hawai'ian island of Kaua'i, which the directors have since credited as the defining choice made in the entire development of the feature, for it not only directed the film's very distinctive appearance but also introduced the concept of 'ohana, a concept of extended family that would end up driving the whole emotional arc of the piece, which was eventually titled Lilo & Stitch.

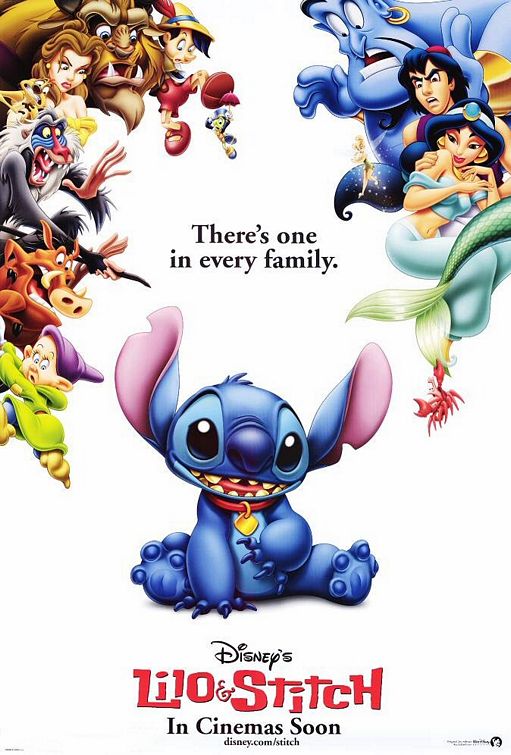

Upon its release in the summer of 2002, Lilo & Stitch managed to do something that no other 2-D Disney film of the '00s had or would do: it turned a profit during its theatrical release (at almost $146 million domestically, it was by more than $50 million the highest-grossing film released after Tarzan, while also being the cheapest). Thanks to the buoyant, cartoony style of the characters, it also boasted the most successful tie-in marketing of any film in that period; it inspired two direct-to-video sequels and a TV series, a Walt Disney World attraction, and is quite the only post-Renaissance Disney project with any kind of noteworthy presence in Disney's corporate branding (by which I mean, Disney Store artwork, and theme park advertisements and character-meets). And this was perhaps the most conspicuously auteurist film ever produced by Disney Animation Studios; not that there is much competition for that title, but even in an alternate universe where Walt and his successors permitted individual filmmakers to run away with a project, like, ever, the totality of Sanders's contributions to the film would still mark it as, above all else, the work of one man's imagination.

His reward for giving this gift to the Walt Disney Company was a new project to direct and develop: American Dog, about a canine TV star and the motley crew of vagabonds he meets when he is stranded in the desert, miles from anything familiar or safe. As is customary for scrapped ideas and controversies, Disney has little other record of what exactly happened during the development of American Dog, but it is known that, following the company's acquisition of Pixar in April, 2006, and the subsequent placement of John Lasseter at the head of all animation production for both studios, he took a good long look at what Sanders had been working on, and found it lacking. He made certain suggestions for how Sanders might be able to improve the material; Sanders resisted; and in December, Sanders was either removed or quit the project, and severed all ties with Disney. He has since found a comfortable position at DreamWorks, with his first project there, How to Train Your Dragon, ready for a spring, 2010 release. American Dog was retitled Bolt, released in November, 2008, and was the best film released under the Walt Disney Feature Animation banner in six years; so perhaps Lasseter's instincts were right. Maybe Sanders's film was going wrong, too quirky or too dark or just too hung up on plot. But I cannot help but be bitter than a man who'd earned as much trust from Disney as Chris Sanders should have would be repaid with second-guessing and orders for improvement by a new executive looking to make his mark - even if that executive was a proven artistic genius like Lasseter. Maybe American Dog would have been a train wreck, and maybe it would have made Bolt look like the tawdriest, trashiest waste of time; we'll never know, and I feel tremendously sad for Sanders that we won't.

As for Lilo & Stitch, well, I guess it's pretty obvious from all that, that I think Sanders's one great shining moment at Disney is a decent thing - a better than decent thing, really. It is flawed in ways that the best Disney features could never imagine, and even among the post-Renaissance films it lacks the cohesiveness and creativity of The Emperor's New Groove; but it is anyways a movie for which I have some pronounced affection, and I would call it the last Disney animated feature of any truly lasting merit, here on the cusp of what we all hope is a return to form with The Princess and the Frog. It is one of the most juvenile Disney films since the '70s - despite the presence of Elvis songs on the soundtrack, this one is pitched squarely at children. As a direct result of that fact, it is to me one of the most appealing and pleasant to watch: it won't put you through any artistic loop-de-loops or demand attention to its intricacies of plot, character or music, but it makes up for that by being warm and inviting, with easy, open sentiment and an eye-popping array of colors.

Besides its similarities to Dumbo in conception (a cheap kiddie movie after some ambitious, grown-up failures) and tone (after the discordant opening 10 minutes, it's as gentle and sweet as any other Disney movie since the elephant picture), Lilo & Stitch has a much more obvious, practical, and objective point of comparison: both films use watercolor backgrounds exclusively, a distinction that is shared by none of the 37 films produced between the two, and is found prior to Dumbo only in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. I understand why Disney stayed away from watercolors so assiduously: at first it was partially a means of distinguishing their high-cost, high-prestige features from their '30s and '40s shorts, which also primarily used watercolors, a cheaper and faster means of producing background paintings than oils. Similarly, watercolors simply don't permit as much detail and depth, and with realism the key concern for so much Disney animation, the soft, flat style of watercolor paintings was absolutely not preferable.

I understand; but I do not have to like. There's something about the very fact that watercolors are so much simpler that is immensely satisfying; they possess a warmth and innocence that oil paintings do not (I think part of my affection for the post-war package films has to do with their occasional use of watercolor; it makes them more agreeably cartoony). It is a softer aesthetic that is soothing on the eye and reminds one of picture books and nostalgic landscape paintings; not appropriate for every context, certainly - imagine a watercolored Sleeping Beauty! the mind revolts - but for the right project, it works so very well. Lilo & Stitch was absolutely the right project.

It was, by design, a much simpler-looking film than the great animation triumphs of the CAPS age, like The Lion King and Beauty and the Beast: there are no shading and lighting effects, few transparent overlays, nothing that aggressively announces itself as computer-animation at all except for spaceships. The character design follows suit: breaking a chain of increasingly graphic, angular shapes and lines that had taken hold at the studio in the mid-1990s, there are virtually no straight lines or right angles on anyone in Lilo & Stitch at all. Everyone is rounded, pudgy, soft - at the time of the film's release, I recall some small measure of praise given to it for depicting the female form as it is seen in life, a bit fuller than the model-thin women in the princess films, but I have no doubt that Sanders and his fellow character designers Byron Howard and Buck Lewis weren't consciously trying to avoid the unfortunate & damaging stereotype of alarmingly fit, physically idealised girls. It just fit in better with the overall aesthetic to give the teenage Nani a little bit of pudge on her thighs, and the mere fact that she thus becomes one of the first reasonably-shaped women in Disney is at most a happy accident.

When I call Lilo & Stitch obviously a movie for kids, I am first and foremost thinking of this rounded, soft aesthetic. With its preponderance of flowing shapes and circle-based character design, it couldn't be a farther cry from the angular Atlantis: The Lost Empire, with its comics-derived style. What Lilo & Stitch rather feels like is one of those television shows aimed for young children, where all of the characters are plushy and rotund, and where the colors are plentiful and imaginative but also washed-out and placid. It is the animation design equivalent of a baby blanket. And since every word I write regresses the age of the movie's ideal viewer, I should stop lest I ultimately argue that Lilo & Stitch is the visual equivalent of those classical music CDs that pregnant women are encouraged to play right into their womb.

My point anyway isn't that the movie is profoundly juvenile or immature, but that it is simple, innocent, and soothing - visually, at least. I suppose if some adult viewer wanted that to be a problem, then a problem it would be; for me, I find the limpid color scheme to be incredibly comforting and lovely to look at. The mere fact that something has a childish appeal to it doesn't mean that it must necessarily therefore be beneath the attention of grown-ups; some of the realest pleasures are the ones that remind us of youth and childhood. For me, the visuals in Lilo & Stitch fall securely in this camp, and the film proves one of the key rules about family entertainment that has been largely in these benighted days of cynical CGI trash-fests: art aimed at children can still be artistically fulfilling, and anything that is artistically fulfilling can be satisfying for any parent or other older viewer. Thus the best "family" entertainment is that which doesn't set itself to dividing parents and children into two intractable camps who must each have their own level of appreciation: you can make kid-friendly material well enough that the kid's parent won't require any innuendos or esoteric references.

Lilo & Stitch absolutely functions this way visually: it also comes very close to working on the same level as a story, although there are some major narrative flaws in the story that aren't really the result of pandering to any age group, but simply an awkward fact of following exposition and plot where they naturally lead, despite the rather gaping tonal conflicts that result. I specifically refer to the film's opening ten minutes, set on the capitol planet of the Galactic Federation, where the rogue scientist Dr. Jumba (David Ogden Stiers, in the last of his five Disney animated features; he'd continue to play the character in the spin-off media) is on trial for illegally creating an abnormal genetic experiment, code-named 626: a little blue thing with four arms, floppy oval ears, graceful feathery spines on its back, and a program for wanton, total destruction and invulnerability coded right into its DNA (the little dude is voiced by Chris Sanders, as a matter of fact, and he's still at it, when necessary; maybe indicating that his falling out with Disney wasn't as bad as that, or maybe just that he likes a fat paycheck, or that he has too much love for the character to see another damage it).

For his crimes, Jumba is sentenced to prison, and 626 to extermination; but he's a tricky bugger and quickly escapes, jacking an escape pod and fleeing to a distant water planet full of uncivilised animals (as is usually the case in sci-fi comedies when a water planet is full of uncivilised animals, they're talking about Earth). There's very little way that the "destructive alien meets, befriends lonely human girl" plot could work without this or similar set-up; yet the opening sequence of Lilo & Stitch exists on a much different plane than the rest of the film. It is like nothing so much as a little tykes version of the Star Wars universe, enlivened by customarily excellent Disney animation; and though it is successfully comic, it jars so badly with the Hawai'i scenes that I'd just as soon think of it as a castaway bit from an entirely different movie - one that is genuinely juvenile and childish, and not in the good way that I was just talking about.

Luckily, that other, much better movie gets going quickly enough: on Kaua'i, there is a little girl named Lilo (Daveigh Chase, who's rather tumbled from the face of the world while her then-friend Dakota Fanning has become an unstoppable force of pure evil), living with her older sister Nani (Tia Carrere, a native Hawai'ian) after their parents died in a car accident. As you'd expect, Lilo is not a tremendously stable, happy girl; her behavior is best described as "difficult", involving strange flights of fancy (feeding peanut butter sandwiches to fish) and morbid obsessions, and this leads to disaster when she locks Nani out of the house on the same day that a ridiculously tough social worker named Cobra Bubbles (Ving Rhames) comes to town to investigate the sisters' rather sub-standard living conditions. In an attempt to keep Lilo happy and well-behaved during the social worker's investigations, Nani takes her to the pound to adopt a dog; and of course the slightly demented Lilo latches onto the most effed-up animal in the facility, which just so happens to be 626, captured after his ship crashed and he was hit by a series of semi-trucks. Lilo renames her "puppy" Stitch, and is completely oblivious to the fact that he wants to destroy everything he can touch - but luckily, Kaua'i is isolated enough (Stitch can't swim) that he cannot unleash the full, city-leveling powers at his disposal.

Anyway, while he's living with the sisters, Stitch begins to observe things that aren't in his programming; he experiences love; and he is touched by the very spirit of 'ohana. And as we are told, and told, and told, and told, "'Ohana means family. Family means nobody gets left behind, or forgotten." I would say that one's tolerance for Lilo & Stitch depends on their tolerance for that phrase, except that I really like the movie a lot, and if I just read that sentence out of context, I'd find it the sickliest Hallmark sentiment imaginable.

The great triumph of this film is the way it blends inordinately gooey levels of sentiment with really bent humor and sci-fi action (enough to get the film a PG-rating; questionable at best, absurd in the face of Disney's numerous G-rated violence parades in the 1990s). The humor keeps the sentiment from getting too disgusting, while the humanism grounds the jokes in characters and situations, and keeps it from turning into the kind of soulless conveyor belt of stupid gags that so many animated films have been in the last decade. It's more or less the one Disney Animation feature that taps into the same great strength of Pixar's films, especially the ones directed by Pete Docter (Monsters, Inc. and the much later Up): real emotion and real comedy, not sequestered in separate boxes, each one for the appropriate moment in the plot, but all tangled up and messed together in a way that is infinitely more effective and meaningful - it's funnier and more touching than anything put together by committee checklist, at any rate.

It is the first Disney animated feature in a while to return to Walt Disney's one true mission: the creation of fully-realised and appealing characters. Fittingly for a film of its professed innocence and visual simplicity, it is a movie without villains, though a number of characters might at one point or another seem pretty nasty, and Stitch himself is right at the top of the list. But the most prominent "bad" characters (including Jumba, sent to Earth to retrieve his creation) are still made likable and cuddly through the judicious application of strong, funny personality, and that aforementioned rounded design. Stitch himself is a magnificent piece of character creation, from Sanders's gargling line deliveries to his physical comedy, to the fact that, yes indeed, he is impossibly cute with his big black eyes and naughty little facial expressions. Even his violent outbursts are cute.

He makes a perfect pair with Lilo, who is also tremendously cute, and wildly unrealistic with her giant Muppet-like head, and who behaves with the intense stoicism of a real human child of similar precocious morbidity, and not some ideal perfect angel. She also has quite a strong personality on her that shades into blissed-out innocent imagination too often to call her preternaturally cynical, although I don't know a better word for her worldview than cynicism. This could be a contradiction; but even little people are contradictory sometimes. She is at any rate one of the better-developed child characters in animated cinema, or in '00s cinema, period. At a time when most children in movies are little wisecracking adults, Lilo, despite her weird level of age-inappropriate knowledge and Elvis obsession, never seems to be anything other than a curiously deranged ten-year-old.

As long as Lilo & Stitch focuses on the relationship between the two title characters, or the deeply amusing and engaging personalities of each individually, it is the best, sweetest Disney movie of its generation; but the lengthy beginning and somewhat shorter climax drag it down at the worst possible points. Making Stitch an alien meant that there had to be a pronounced science fiction element, and at times this works: the subplot involving Jumba's Stitch-hunt alongside the neurotic one-eyed alien Pleakley (Kevin McDonald) is as amusing as anything else in the film. But when the narrative enters a more "dramatic" sci-fi phase, it stops dead in its tracks to let the universe-building occur, and to toss around plot developments that are too serious and political to fit into the defiantly gentle main body of the narrative. This conflict between tones is alone enough to keep Lilo & Stitch from attaining greatness, although it is awfully good nevertheless.

No amount of plot mishap can, after all, take away its marvelous design mentality; nor the sometimes breathtaking beauty of its animation, which though limited in its ambition still reaches some lovely heights (a shot of Stitch looking into the clear water and seeing Lilo swimming underneath him is one of the film's most elegant moments. The characters are animated with a great deal of respect for their soft edges, but also their physicality, especially Lilo (supervised by Andreas Deja, who ended up here after abandoning the doomed Kingdom of the Sun project along with director Roger Allers) and Stitch (supervised by Alex Kupershmidt, whose work on the hyenas in The Lion King and some minor characters in Mulan indicated none of his great gift for physical comedy and transformation, given full room to explode with this outstandingly expressive character). And it's always a good thing when the title characters are exceedingly well-animated, non?

Best of all, though, is that the film is genuinely sweet and funny and totally entertaining. Sanders and DeBlois had a real gift for making something pitched so young work so outstandingly that you'd never really stop to think that, as a grown-up, you're not meant to like it. This is the last and most important of the film's similarities to Dumbo, another cartoon for little ones that still manages to be a masterpiece of 1940s American cinema. Lilo & Stitch isn't as good as that, of course, but it's far more sincere and delightful than seems possible given the state of the company and 2-D animation in 2002. It is completely and without reservation a wonderful family movie, arguably the hardest of all genres to get right - whatever happened to Sanders or Disney in the years to follow doesn't so much as put a nick in that gleaming achievement.

Sanders was a character designer on a number of 1980s cartoon series, when he was first hired by the Walt Disney Company to work on The Rescuers Down Under. From here he was quickly moved to the story department, helping to develop a handful of projects from Beauty and the Beast to Mulan, and in the process establishing himself as one of the great talents at Disney, if one whose contributions went unsung (for even among animation buffs, storymen are only very rarely accorded any degree of fame or fandom.

It was after the completion of Mulan that he was given his big break in the company. Many, many years earlier, even before he'd joined up with Disney, Sanders had created a little alien with a big mouthful of teeth and a propensity for causing massive amounts of destruction wherever he want, named "Stitch". He'd never been able to sell anyone on the character, though, and his sketches lay in the dark for many years, waiting for the right moment. That moment came when Michael Eisner concluded that, after the middling box-office returns of the highly prestigious and costly Pocahontas and The Hunchback of Notre Dame, the studio needed to make something on the cheap, something simple and straightforward and absolutely family-friendly: a little kid's cartoon, essentially, reminiscent of how after the the massive expenses of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, and Fantasia, the company had followed with its all-time cheapest feature, the delicate little fable Dumbo (there are other reasons why that feature is an important touchstone at this point, and I will get to them soon enough). Sanders's Stitch project, which at the time involved the character as an intergalactic con-man in flight from justice ending up befriending a little girl in Kansas, got the green-light, I suppose in recognition of that man's significant contributions to the company over the years; it was going to be the second feature produced entirely at the Florida arm of the studios, following Mulan.

While the executives fussed and bothered over the extraordinarily costly Tarzan and Treasure Planet, the game-changing adventure film Atlantis: The Lost Empire, and the nightmare happening with Kingdom of the Sun/The Emperor's New Groove, Chris Sanders and his co-creator Dean DeBlois (the two had previously led the writing of Mulan, after DeBlois arrived at Disney from the disintegration of Don Bluth Productions in the mid-1990s) were able to work with a stunning lack of corporate oversight, being permitted to make their movie essentially as they thought best. Along the way, the action was switched to the Hawai'ian island of Kaua'i, which the directors have since credited as the defining choice made in the entire development of the feature, for it not only directed the film's very distinctive appearance but also introduced the concept of 'ohana, a concept of extended family that would end up driving the whole emotional arc of the piece, which was eventually titled Lilo & Stitch.

Upon its release in the summer of 2002, Lilo & Stitch managed to do something that no other 2-D Disney film of the '00s had or would do: it turned a profit during its theatrical release (at almost $146 million domestically, it was by more than $50 million the highest-grossing film released after Tarzan, while also being the cheapest). Thanks to the buoyant, cartoony style of the characters, it also boasted the most successful tie-in marketing of any film in that period; it inspired two direct-to-video sequels and a TV series, a Walt Disney World attraction, and is quite the only post-Renaissance Disney project with any kind of noteworthy presence in Disney's corporate branding (by which I mean, Disney Store artwork, and theme park advertisements and character-meets). And this was perhaps the most conspicuously auteurist film ever produced by Disney Animation Studios; not that there is much competition for that title, but even in an alternate universe where Walt and his successors permitted individual filmmakers to run away with a project, like, ever, the totality of Sanders's contributions to the film would still mark it as, above all else, the work of one man's imagination.

His reward for giving this gift to the Walt Disney Company was a new project to direct and develop: American Dog, about a canine TV star and the motley crew of vagabonds he meets when he is stranded in the desert, miles from anything familiar or safe. As is customary for scrapped ideas and controversies, Disney has little other record of what exactly happened during the development of American Dog, but it is known that, following the company's acquisition of Pixar in April, 2006, and the subsequent placement of John Lasseter at the head of all animation production for both studios, he took a good long look at what Sanders had been working on, and found it lacking. He made certain suggestions for how Sanders might be able to improve the material; Sanders resisted; and in December, Sanders was either removed or quit the project, and severed all ties with Disney. He has since found a comfortable position at DreamWorks, with his first project there, How to Train Your Dragon, ready for a spring, 2010 release. American Dog was retitled Bolt, released in November, 2008, and was the best film released under the Walt Disney Feature Animation banner in six years; so perhaps Lasseter's instincts were right. Maybe Sanders's film was going wrong, too quirky or too dark or just too hung up on plot. But I cannot help but be bitter than a man who'd earned as much trust from Disney as Chris Sanders should have would be repaid with second-guessing and orders for improvement by a new executive looking to make his mark - even if that executive was a proven artistic genius like Lasseter. Maybe American Dog would have been a train wreck, and maybe it would have made Bolt look like the tawdriest, trashiest waste of time; we'll never know, and I feel tremendously sad for Sanders that we won't.

As for Lilo & Stitch, well, I guess it's pretty obvious from all that, that I think Sanders's one great shining moment at Disney is a decent thing - a better than decent thing, really. It is flawed in ways that the best Disney features could never imagine, and even among the post-Renaissance films it lacks the cohesiveness and creativity of The Emperor's New Groove; but it is anyways a movie for which I have some pronounced affection, and I would call it the last Disney animated feature of any truly lasting merit, here on the cusp of what we all hope is a return to form with The Princess and the Frog. It is one of the most juvenile Disney films since the '70s - despite the presence of Elvis songs on the soundtrack, this one is pitched squarely at children. As a direct result of that fact, it is to me one of the most appealing and pleasant to watch: it won't put you through any artistic loop-de-loops or demand attention to its intricacies of plot, character or music, but it makes up for that by being warm and inviting, with easy, open sentiment and an eye-popping array of colors.

Besides its similarities to Dumbo in conception (a cheap kiddie movie after some ambitious, grown-up failures) and tone (after the discordant opening 10 minutes, it's as gentle and sweet as any other Disney movie since the elephant picture), Lilo & Stitch has a much more obvious, practical, and objective point of comparison: both films use watercolor backgrounds exclusively, a distinction that is shared by none of the 37 films produced between the two, and is found prior to Dumbo only in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. I understand why Disney stayed away from watercolors so assiduously: at first it was partially a means of distinguishing their high-cost, high-prestige features from their '30s and '40s shorts, which also primarily used watercolors, a cheaper and faster means of producing background paintings than oils. Similarly, watercolors simply don't permit as much detail and depth, and with realism the key concern for so much Disney animation, the soft, flat style of watercolor paintings was absolutely not preferable.

I understand; but I do not have to like. There's something about the very fact that watercolors are so much simpler that is immensely satisfying; they possess a warmth and innocence that oil paintings do not (I think part of my affection for the post-war package films has to do with their occasional use of watercolor; it makes them more agreeably cartoony). It is a softer aesthetic that is soothing on the eye and reminds one of picture books and nostalgic landscape paintings; not appropriate for every context, certainly - imagine a watercolored Sleeping Beauty! the mind revolts - but for the right project, it works so very well. Lilo & Stitch was absolutely the right project.

It was, by design, a much simpler-looking film than the great animation triumphs of the CAPS age, like The Lion King and Beauty and the Beast: there are no shading and lighting effects, few transparent overlays, nothing that aggressively announces itself as computer-animation at all except for spaceships. The character design follows suit: breaking a chain of increasingly graphic, angular shapes and lines that had taken hold at the studio in the mid-1990s, there are virtually no straight lines or right angles on anyone in Lilo & Stitch at all. Everyone is rounded, pudgy, soft - at the time of the film's release, I recall some small measure of praise given to it for depicting the female form as it is seen in life, a bit fuller than the model-thin women in the princess films, but I have no doubt that Sanders and his fellow character designers Byron Howard and Buck Lewis weren't consciously trying to avoid the unfortunate & damaging stereotype of alarmingly fit, physically idealised girls. It just fit in better with the overall aesthetic to give the teenage Nani a little bit of pudge on her thighs, and the mere fact that she thus becomes one of the first reasonably-shaped women in Disney is at most a happy accident.

When I call Lilo & Stitch obviously a movie for kids, I am first and foremost thinking of this rounded, soft aesthetic. With its preponderance of flowing shapes and circle-based character design, it couldn't be a farther cry from the angular Atlantis: The Lost Empire, with its comics-derived style. What Lilo & Stitch rather feels like is one of those television shows aimed for young children, where all of the characters are plushy and rotund, and where the colors are plentiful and imaginative but also washed-out and placid. It is the animation design equivalent of a baby blanket. And since every word I write regresses the age of the movie's ideal viewer, I should stop lest I ultimately argue that Lilo & Stitch is the visual equivalent of those classical music CDs that pregnant women are encouraged to play right into their womb.

My point anyway isn't that the movie is profoundly juvenile or immature, but that it is simple, innocent, and soothing - visually, at least. I suppose if some adult viewer wanted that to be a problem, then a problem it would be; for me, I find the limpid color scheme to be incredibly comforting and lovely to look at. The mere fact that something has a childish appeal to it doesn't mean that it must necessarily therefore be beneath the attention of grown-ups; some of the realest pleasures are the ones that remind us of youth and childhood. For me, the visuals in Lilo & Stitch fall securely in this camp, and the film proves one of the key rules about family entertainment that has been largely in these benighted days of cynical CGI trash-fests: art aimed at children can still be artistically fulfilling, and anything that is artistically fulfilling can be satisfying for any parent or other older viewer. Thus the best "family" entertainment is that which doesn't set itself to dividing parents and children into two intractable camps who must each have their own level of appreciation: you can make kid-friendly material well enough that the kid's parent won't require any innuendos or esoteric references.

Lilo & Stitch absolutely functions this way visually: it also comes very close to working on the same level as a story, although there are some major narrative flaws in the story that aren't really the result of pandering to any age group, but simply an awkward fact of following exposition and plot where they naturally lead, despite the rather gaping tonal conflicts that result. I specifically refer to the film's opening ten minutes, set on the capitol planet of the Galactic Federation, where the rogue scientist Dr. Jumba (David Ogden Stiers, in the last of his five Disney animated features; he'd continue to play the character in the spin-off media) is on trial for illegally creating an abnormal genetic experiment, code-named 626: a little blue thing with four arms, floppy oval ears, graceful feathery spines on its back, and a program for wanton, total destruction and invulnerability coded right into its DNA (the little dude is voiced by Chris Sanders, as a matter of fact, and he's still at it, when necessary; maybe indicating that his falling out with Disney wasn't as bad as that, or maybe just that he likes a fat paycheck, or that he has too much love for the character to see another damage it).

For his crimes, Jumba is sentenced to prison, and 626 to extermination; but he's a tricky bugger and quickly escapes, jacking an escape pod and fleeing to a distant water planet full of uncivilised animals (as is usually the case in sci-fi comedies when a water planet is full of uncivilised animals, they're talking about Earth). There's very little way that the "destructive alien meets, befriends lonely human girl" plot could work without this or similar set-up; yet the opening sequence of Lilo & Stitch exists on a much different plane than the rest of the film. It is like nothing so much as a little tykes version of the Star Wars universe, enlivened by customarily excellent Disney animation; and though it is successfully comic, it jars so badly with the Hawai'i scenes that I'd just as soon think of it as a castaway bit from an entirely different movie - one that is genuinely juvenile and childish, and not in the good way that I was just talking about.

Luckily, that other, much better movie gets going quickly enough: on Kaua'i, there is a little girl named Lilo (Daveigh Chase, who's rather tumbled from the face of the world while her then-friend Dakota Fanning has become an unstoppable force of pure evil), living with her older sister Nani (Tia Carrere, a native Hawai'ian) after their parents died in a car accident. As you'd expect, Lilo is not a tremendously stable, happy girl; her behavior is best described as "difficult", involving strange flights of fancy (feeding peanut butter sandwiches to fish) and morbid obsessions, and this leads to disaster when she locks Nani out of the house on the same day that a ridiculously tough social worker named Cobra Bubbles (Ving Rhames) comes to town to investigate the sisters' rather sub-standard living conditions. In an attempt to keep Lilo happy and well-behaved during the social worker's investigations, Nani takes her to the pound to adopt a dog; and of course the slightly demented Lilo latches onto the most effed-up animal in the facility, which just so happens to be 626, captured after his ship crashed and he was hit by a series of semi-trucks. Lilo renames her "puppy" Stitch, and is completely oblivious to the fact that he wants to destroy everything he can touch - but luckily, Kaua'i is isolated enough (Stitch can't swim) that he cannot unleash the full, city-leveling powers at his disposal.

Anyway, while he's living with the sisters, Stitch begins to observe things that aren't in his programming; he experiences love; and he is touched by the very spirit of 'ohana. And as we are told, and told, and told, and told, "'Ohana means family. Family means nobody gets left behind, or forgotten." I would say that one's tolerance for Lilo & Stitch depends on their tolerance for that phrase, except that I really like the movie a lot, and if I just read that sentence out of context, I'd find it the sickliest Hallmark sentiment imaginable.

The great triumph of this film is the way it blends inordinately gooey levels of sentiment with really bent humor and sci-fi action (enough to get the film a PG-rating; questionable at best, absurd in the face of Disney's numerous G-rated violence parades in the 1990s). The humor keeps the sentiment from getting too disgusting, while the humanism grounds the jokes in characters and situations, and keeps it from turning into the kind of soulless conveyor belt of stupid gags that so many animated films have been in the last decade. It's more or less the one Disney Animation feature that taps into the same great strength of Pixar's films, especially the ones directed by Pete Docter (Monsters, Inc. and the much later Up): real emotion and real comedy, not sequestered in separate boxes, each one for the appropriate moment in the plot, but all tangled up and messed together in a way that is infinitely more effective and meaningful - it's funnier and more touching than anything put together by committee checklist, at any rate.

It is the first Disney animated feature in a while to return to Walt Disney's one true mission: the creation of fully-realised and appealing characters. Fittingly for a film of its professed innocence and visual simplicity, it is a movie without villains, though a number of characters might at one point or another seem pretty nasty, and Stitch himself is right at the top of the list. But the most prominent "bad" characters (including Jumba, sent to Earth to retrieve his creation) are still made likable and cuddly through the judicious application of strong, funny personality, and that aforementioned rounded design. Stitch himself is a magnificent piece of character creation, from Sanders's gargling line deliveries to his physical comedy, to the fact that, yes indeed, he is impossibly cute with his big black eyes and naughty little facial expressions. Even his violent outbursts are cute.

He makes a perfect pair with Lilo, who is also tremendously cute, and wildly unrealistic with her giant Muppet-like head, and who behaves with the intense stoicism of a real human child of similar precocious morbidity, and not some ideal perfect angel. She also has quite a strong personality on her that shades into blissed-out innocent imagination too often to call her preternaturally cynical, although I don't know a better word for her worldview than cynicism. This could be a contradiction; but even little people are contradictory sometimes. She is at any rate one of the better-developed child characters in animated cinema, or in '00s cinema, period. At a time when most children in movies are little wisecracking adults, Lilo, despite her weird level of age-inappropriate knowledge and Elvis obsession, never seems to be anything other than a curiously deranged ten-year-old.

As long as Lilo & Stitch focuses on the relationship between the two title characters, or the deeply amusing and engaging personalities of each individually, it is the best, sweetest Disney movie of its generation; but the lengthy beginning and somewhat shorter climax drag it down at the worst possible points. Making Stitch an alien meant that there had to be a pronounced science fiction element, and at times this works: the subplot involving Jumba's Stitch-hunt alongside the neurotic one-eyed alien Pleakley (Kevin McDonald) is as amusing as anything else in the film. But when the narrative enters a more "dramatic" sci-fi phase, it stops dead in its tracks to let the universe-building occur, and to toss around plot developments that are too serious and political to fit into the defiantly gentle main body of the narrative. This conflict between tones is alone enough to keep Lilo & Stitch from attaining greatness, although it is awfully good nevertheless.

No amount of plot mishap can, after all, take away its marvelous design mentality; nor the sometimes breathtaking beauty of its animation, which though limited in its ambition still reaches some lovely heights (a shot of Stitch looking into the clear water and seeing Lilo swimming underneath him is one of the film's most elegant moments. The characters are animated with a great deal of respect for their soft edges, but also their physicality, especially Lilo (supervised by Andreas Deja, who ended up here after abandoning the doomed Kingdom of the Sun project along with director Roger Allers) and Stitch (supervised by Alex Kupershmidt, whose work on the hyenas in The Lion King and some minor characters in Mulan indicated none of his great gift for physical comedy and transformation, given full room to explode with this outstandingly expressive character). And it's always a good thing when the title characters are exceedingly well-animated, non?

Best of all, though, is that the film is genuinely sweet and funny and totally entertaining. Sanders and DeBlois had a real gift for making something pitched so young work so outstandingly that you'd never really stop to think that, as a grown-up, you're not meant to like it. This is the last and most important of the film's similarities to Dumbo, another cartoon for little ones that still manages to be a masterpiece of 1940s American cinema. Lilo & Stitch isn't as good as that, of course, but it's far more sincere and delightful than seems possible given the state of the company and 2-D animation in 2002. It is completely and without reservation a wonderful family movie, arguably the hardest of all genres to get right - whatever happened to Sanders or Disney in the years to follow doesn't so much as put a nick in that gleaming achievement.

Categories: animation, comedies, disney, movies allegedly for children, science fiction