Disney Animation: One Simple Theme, Repeating

The first five animated features produced by the Disney Studios between 1937 and 1942 represent a level of sustained artistic achievement virtually unheard of elsewhere in cinema history. Pixar Animation Studios has a good shot at replicating the feat if they keep up their current level for just a couple more years, but outside of that I can think of no director or creative team that made so many stone-cold masterpieces in such a brief span of time, and Disney's achievement is all the more impressive considering what they were facing in those years: crippling budgetary problems, the loss of staff due to the outbreak of World War II, and perhaps most damningly, an increasingly overworked, under-payed animation staff that finally went on strike in the summer of 1941, during the production of Dumbo. In addition to costing Walt Disney some of his finest animators, such as Art Babbitt (whose firing was the trigger for the strike) and Bill Tytla, this event marked the end of the spirit of family and comradeship that had been part of the studio's fabric ever since it inception. Hereafter, it was Boss Walt and his employees, although it is a strange coincidence that rise of what we might call "personality-based" animation at Disney dates to around this same time; I refer to the sequences and characters that can be clearly identified as the work of a specific supervising animator (invariably, one of Walt's favorites, often the ones who'd sided with him during the strike). This trend began with Fantasia, with Walt's uncharacteristically hands-off approach to the animation, and started to become truly prominent with Norm Ferguson's "Pink Elephants on Parade" sequence in Dumbo; during the 1940s it would continue to become the case until finally, in the 1950s, we reach the point where even a casual fan can readily identify a character by the identity of the its lead animator.

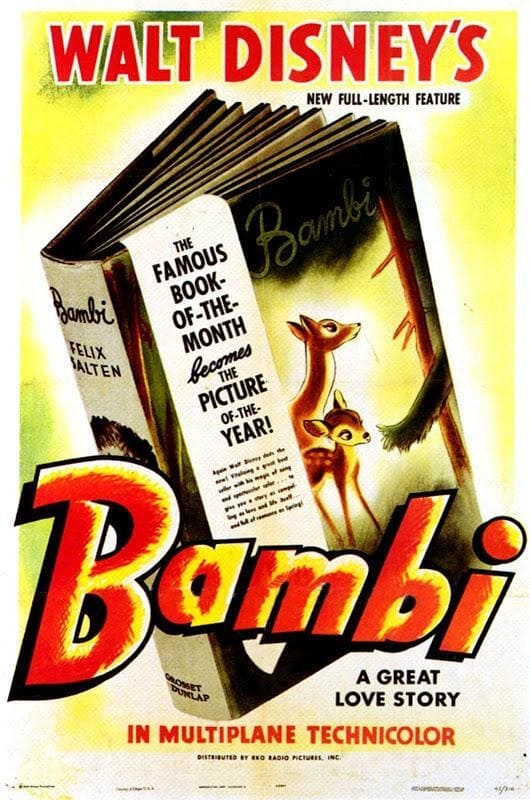

But none of this internal intrigue can be spotted in Bambi, released in August 1942 as a determined, defiant look back at the nature of Disney animation when money was readily available and the only thing that mattered was that Walt's visionary idea would be captured no matter the time or cost. A project, based upon Felix Salten's much-praised novel, that had been kicking around for years as one of the many possible successors to Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs but set aside when the storymen couldn't figure out how to soften its grim edges, the film is first and above all an illustration of Walt Disney's well-known fascination with nature and the animal kingdom. It is the most plotless of all the studio's animated features, containing nothing that could be named "drama" according to its classical sense: there is no conflict that is not resolved essentially at the moment that is raised, and except for the repeated threat of hunters in the forest, nothing that could be considered a narrative throughline. It is the story of two years in the life of a deer, beginning with his birth and ending with the birth of his two fawns, and what happens in between is nothing but a series of vignettes, like snapshots of particularly fond or traumatic moments. Of all the other movies in Disney's history, it is closest to the later True Life Adventures, in which the camera is turned towards animals behaving as animals, just for the sake of it.

The guiding principal behind this film was realism above all; Walt desired that it look as much like real animals in real woods as could possibly be achieved, and this provided the greatest challenge that his animators had yet experienced. It was a far cry indeed from the extremely simple Dumbo, the film that defined much of what Disney animation was to look like in the years to follow; this is largely because the production of Bambi was started nearly a year and half earlier - around the same time as animation began on Fantasia, in fact - and only the diabolically complex animation kept Bambi from reaching theatres until well after the studio had effectively abandoned the incredible detail and crazy ambition that defined its visuals. We might even suppose that the difficulties of creating Bambi had as much to do with the studio's abandonment of that ambition as the wild success of Dumbo did.

Whatever the case, the money and time were well spent indeed on Bambi, which remains the most realistic of all the studios' films. The cast is made up entirely of animals, virtually all of which are drawn to look as close to their physical counterparts as possible (the single exception: some of the rabbits, in some of the scenes, move in distinctly anthropomorphic ways). A host of living animals were brought into the studio for this reason, leading some of the animators to complain that it was becoming a bit zoo-like, but the effect is breathtaking: the subtleties of movement and musculature are as close to perfection as imaginable (Disney wouldn't even attempt to create animals this realistic again until The Lion King, more than 50 years later), and the film vies only with Pinocchio as the most technically accomplished work of animation to come from the studio's Golden Age.

To accompany this wonderful animation, the film also boasts absurdly detailed backgrounds: in some scenes, approaching photorealism more than any other animated feature that I have ever seen; in others, suggesting the rich landscape paintings of the 19th Century Hudson River School. No other animated movie has represented living nature to the same wild success as Bambi. Even the transition from unnervingly realistic representations of some locations to the more painterly style of others is achieved so delicately that it hardly registers; the most impressionistic scenes are the ones that are the most emotionally potent, for good or bad (thus the meadow, site of the most infamous death in movie history, is sketched out in looser strokes than the interior of the woods, which is an essentially peaceful and familiar space). This reaches its furthest expression in what is to me the most visually impressive scene in the film, the fight between grown-up Bambi and another buck for the doe Faline, a scene lit like the edgiest and most brutal film noir, reducing the two male deer to nearly abstract shapes clashing against violent red backgrounds.

We've already seen what an excess of artistry did to Pinocchio and Fantasia financially; but Bambi manages to avoid being so arch as they are, even while it is nowhere near so easy and family-friendly as Dumbo. For a start, the character design, while realistic, is also just about as wholly appealing as anything else in the studio's history; Bambi himself is as instantly sympathetic a character as anyone else in animation, equaling the impossibly charming Dumbo. In the by-now standard role as the comic side character who gets to have all the spunk while the protagonist remains heroic, we have the truly outstanding Thumper the rabbit, a character as easily cited as the first in a long, long line of insipid Disney comic figures as he is called one of the studio's great achievements in the 1940s; but I will leave others to make the negative argument. For me, Thumper as a child is one of the great triumphs of the Golden Age; not only the first Disney character with a great vocal performance (that of four-year old Peter Behn), but one of the warmest and best-realised in his design and animation, the first great success of animator Ollie Johnston, one of the most legendary of all Disney artists and the individual who had the most to say about physical contact between characters, and how that could be used to develop story and emotion (in Bambi, that mentality can be best observed in the classic "skating" scene, with Thumper trying to help the wobbly Bambi find his feet on the ice).

Even though there is no "story", even though the film is about a deer, Bambi is also one of the easiest Disney films to appreciate on a personal level. Everything that Bambi experiences is more or less common to all human people: he is born, finds new places and is amazed by them (and it helps immensely that the viewer is also amazed, given the richness of the visuals), makes friends, loses loved ones, falls in love, learns to be responsible. It is not a coming-of-age story, but a going-through-life story, captured in fine detail but without emotional badgering to make sure we get there. Take, for instance, the death of his mother. For all that this is the most well-remembered part of the movie, it is achieved swiftly and without brutal lingering. Gunshot, running, Bambi calls for her, "Your mother can't be with you anymore". From the moment that Man makes his presence felt to the beginning of the next sequence, in which Bambi is all grown up and absolutely free from trauma, takes less than five minutes; not because the sequence doesn't matter, but because the filmmakers don't need to beat us up with it. By presenting the sequence so simply, that one line of dialogue explaining the whole situation, the film lets us remember that feeling, or imagine that feeling (oh, the poor generations and generations of children who imagined Mommy dying for the first time when they heard that sentence!), and read our own feeling into Bambi's confused look and downturned eyes, and the expressionistic snowstorm that follows. We don't need an hour of "what is it like to be loss a mother" claptrap, because it would be redundant to the impact of those few seconds (which didn't keep Disney from exploring that very topic in Bambi II, one of the most pointless of its many pointless direct-to-video sequels, 64 years later). And that is the progression of just about every sequence in the movie: here is a moment, feel it, move on. It's a storytelling mode that a family-oriented studio could never get away with today - I don't really know how they got away with it in 1942, but maybe that's part of the reason it took a 1947 re-release for Bambi to make its money back.

Still, it's impressive how much of life the film packs into a very fleet 70 minutes: innocence, grief, hope, adulthood, sex - yes, sex! Of course, sex is something that is supposed to be totally absent from Disney films, and for the most part it is kept very safely away. Do you think that Snow White and Prince Charming really went off to that castle in the clouds and fucked like bunnies? Of course not. It is virtually unimaginable, and despite the preponderance of Disney character porn, the studio did an awfully good job of making sure their characters are totally sexless. When I try to visualise the bedroom activities of Snow White, I see a Barbie and Ken doll getting rubbed together. But in Bambi, the intimations of sexuality are shockingly clear and right on the surface, in the "twitterpated" scene. In a small way: Flower the skunk gets kissed and goes really rigid. In a huge way: Thumber gets kissed and starts vibrating uncontrollably, ramrod straight; when the girl rabbit presses his nose and calms him down, he sprawls out limply on the ground. It's only barely subtext at that point, and while it's coded enough that no child would ever think of it, I'm more than a little surprised that Walt Disney - to say nothing of the Hayes Office- was okay with letting it go out like that. But I'm glad it was there; it adds another degree of fullness to a film that, despite featuring not a single human being onscreen, speaks to everything about the human condition, arguably the last of the Disney features that was meant to speak not just to children, and not, to indulge in Disney-sanctified cliché, the child in an adult's heart, but to actual adults, though by no means is this a film that a kid couldn't love - many generations of kids have. But even though it is much sweeter and funnier than the book, this is still an unexpectedly serious movie (it's not even a musical to speak of; three songs, and all non-diegetic), the last gasp of a maturity and gravity that would immediately disappear from Disney's features, and only reappear in starts and fits over the years to come.

But none of this internal intrigue can be spotted in Bambi, released in August 1942 as a determined, defiant look back at the nature of Disney animation when money was readily available and the only thing that mattered was that Walt's visionary idea would be captured no matter the time or cost. A project, based upon Felix Salten's much-praised novel, that had been kicking around for years as one of the many possible successors to Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs but set aside when the storymen couldn't figure out how to soften its grim edges, the film is first and above all an illustration of Walt Disney's well-known fascination with nature and the animal kingdom. It is the most plotless of all the studio's animated features, containing nothing that could be named "drama" according to its classical sense: there is no conflict that is not resolved essentially at the moment that is raised, and except for the repeated threat of hunters in the forest, nothing that could be considered a narrative throughline. It is the story of two years in the life of a deer, beginning with his birth and ending with the birth of his two fawns, and what happens in between is nothing but a series of vignettes, like snapshots of particularly fond or traumatic moments. Of all the other movies in Disney's history, it is closest to the later True Life Adventures, in which the camera is turned towards animals behaving as animals, just for the sake of it.

The guiding principal behind this film was realism above all; Walt desired that it look as much like real animals in real woods as could possibly be achieved, and this provided the greatest challenge that his animators had yet experienced. It was a far cry indeed from the extremely simple Dumbo, the film that defined much of what Disney animation was to look like in the years to follow; this is largely because the production of Bambi was started nearly a year and half earlier - around the same time as animation began on Fantasia, in fact - and only the diabolically complex animation kept Bambi from reaching theatres until well after the studio had effectively abandoned the incredible detail and crazy ambition that defined its visuals. We might even suppose that the difficulties of creating Bambi had as much to do with the studio's abandonment of that ambition as the wild success of Dumbo did.

Whatever the case, the money and time were well spent indeed on Bambi, which remains the most realistic of all the studios' films. The cast is made up entirely of animals, virtually all of which are drawn to look as close to their physical counterparts as possible (the single exception: some of the rabbits, in some of the scenes, move in distinctly anthropomorphic ways). A host of living animals were brought into the studio for this reason, leading some of the animators to complain that it was becoming a bit zoo-like, but the effect is breathtaking: the subtleties of movement and musculature are as close to perfection as imaginable (Disney wouldn't even attempt to create animals this realistic again until The Lion King, more than 50 years later), and the film vies only with Pinocchio as the most technically accomplished work of animation to come from the studio's Golden Age.

To accompany this wonderful animation, the film also boasts absurdly detailed backgrounds: in some scenes, approaching photorealism more than any other animated feature that I have ever seen; in others, suggesting the rich landscape paintings of the 19th Century Hudson River School. No other animated movie has represented living nature to the same wild success as Bambi. Even the transition from unnervingly realistic representations of some locations to the more painterly style of others is achieved so delicately that it hardly registers; the most impressionistic scenes are the ones that are the most emotionally potent, for good or bad (thus the meadow, site of the most infamous death in movie history, is sketched out in looser strokes than the interior of the woods, which is an essentially peaceful and familiar space). This reaches its furthest expression in what is to me the most visually impressive scene in the film, the fight between grown-up Bambi and another buck for the doe Faline, a scene lit like the edgiest and most brutal film noir, reducing the two male deer to nearly abstract shapes clashing against violent red backgrounds.

We've already seen what an excess of artistry did to Pinocchio and Fantasia financially; but Bambi manages to avoid being so arch as they are, even while it is nowhere near so easy and family-friendly as Dumbo. For a start, the character design, while realistic, is also just about as wholly appealing as anything else in the studio's history; Bambi himself is as instantly sympathetic a character as anyone else in animation, equaling the impossibly charming Dumbo. In the by-now standard role as the comic side character who gets to have all the spunk while the protagonist remains heroic, we have the truly outstanding Thumper the rabbit, a character as easily cited as the first in a long, long line of insipid Disney comic figures as he is called one of the studio's great achievements in the 1940s; but I will leave others to make the negative argument. For me, Thumper as a child is one of the great triumphs of the Golden Age; not only the first Disney character with a great vocal performance (that of four-year old Peter Behn), but one of the warmest and best-realised in his design and animation, the first great success of animator Ollie Johnston, one of the most legendary of all Disney artists and the individual who had the most to say about physical contact between characters, and how that could be used to develop story and emotion (in Bambi, that mentality can be best observed in the classic "skating" scene, with Thumper trying to help the wobbly Bambi find his feet on the ice).

Even though there is no "story", even though the film is about a deer, Bambi is also one of the easiest Disney films to appreciate on a personal level. Everything that Bambi experiences is more or less common to all human people: he is born, finds new places and is amazed by them (and it helps immensely that the viewer is also amazed, given the richness of the visuals), makes friends, loses loved ones, falls in love, learns to be responsible. It is not a coming-of-age story, but a going-through-life story, captured in fine detail but without emotional badgering to make sure we get there. Take, for instance, the death of his mother. For all that this is the most well-remembered part of the movie, it is achieved swiftly and without brutal lingering. Gunshot, running, Bambi calls for her, "Your mother can't be with you anymore". From the moment that Man makes his presence felt to the beginning of the next sequence, in which Bambi is all grown up and absolutely free from trauma, takes less than five minutes; not because the sequence doesn't matter, but because the filmmakers don't need to beat us up with it. By presenting the sequence so simply, that one line of dialogue explaining the whole situation, the film lets us remember that feeling, or imagine that feeling (oh, the poor generations and generations of children who imagined Mommy dying for the first time when they heard that sentence!), and read our own feeling into Bambi's confused look and downturned eyes, and the expressionistic snowstorm that follows. We don't need an hour of "what is it like to be loss a mother" claptrap, because it would be redundant to the impact of those few seconds (which didn't keep Disney from exploring that very topic in Bambi II, one of the most pointless of its many pointless direct-to-video sequels, 64 years later). And that is the progression of just about every sequence in the movie: here is a moment, feel it, move on. It's a storytelling mode that a family-oriented studio could never get away with today - I don't really know how they got away with it in 1942, but maybe that's part of the reason it took a 1947 re-release for Bambi to make its money back.

Still, it's impressive how much of life the film packs into a very fleet 70 minutes: innocence, grief, hope, adulthood, sex - yes, sex! Of course, sex is something that is supposed to be totally absent from Disney films, and for the most part it is kept very safely away. Do you think that Snow White and Prince Charming really went off to that castle in the clouds and fucked like bunnies? Of course not. It is virtually unimaginable, and despite the preponderance of Disney character porn, the studio did an awfully good job of making sure their characters are totally sexless. When I try to visualise the bedroom activities of Snow White, I see a Barbie and Ken doll getting rubbed together. But in Bambi, the intimations of sexuality are shockingly clear and right on the surface, in the "twitterpated" scene. In a small way: Flower the skunk gets kissed and goes really rigid. In a huge way: Thumber gets kissed and starts vibrating uncontrollably, ramrod straight; when the girl rabbit presses his nose and calms him down, he sprawls out limply on the ground. It's only barely subtext at that point, and while it's coded enough that no child would ever think of it, I'm more than a little surprised that Walt Disney - to say nothing of the Hayes Office- was okay with letting it go out like that. But I'm glad it was there; it adds another degree of fullness to a film that, despite featuring not a single human being onscreen, speaks to everything about the human condition, arguably the last of the Disney features that was meant to speak not just to children, and not, to indulge in Disney-sanctified cliché, the child in an adult's heart, but to actual adults, though by no means is this a film that a kid couldn't love - many generations of kids have. But even though it is much sweeter and funnier than the book, this is still an unexpectedly serious movie (it's not even a musical to speak of; three songs, and all non-diegetic), the last gasp of a maturity and gravity that would immediately disappear from Disney's features, and only reappear in starts and fits over the years to come.