Disney Animation: Merrily on our way to nowhere in particular

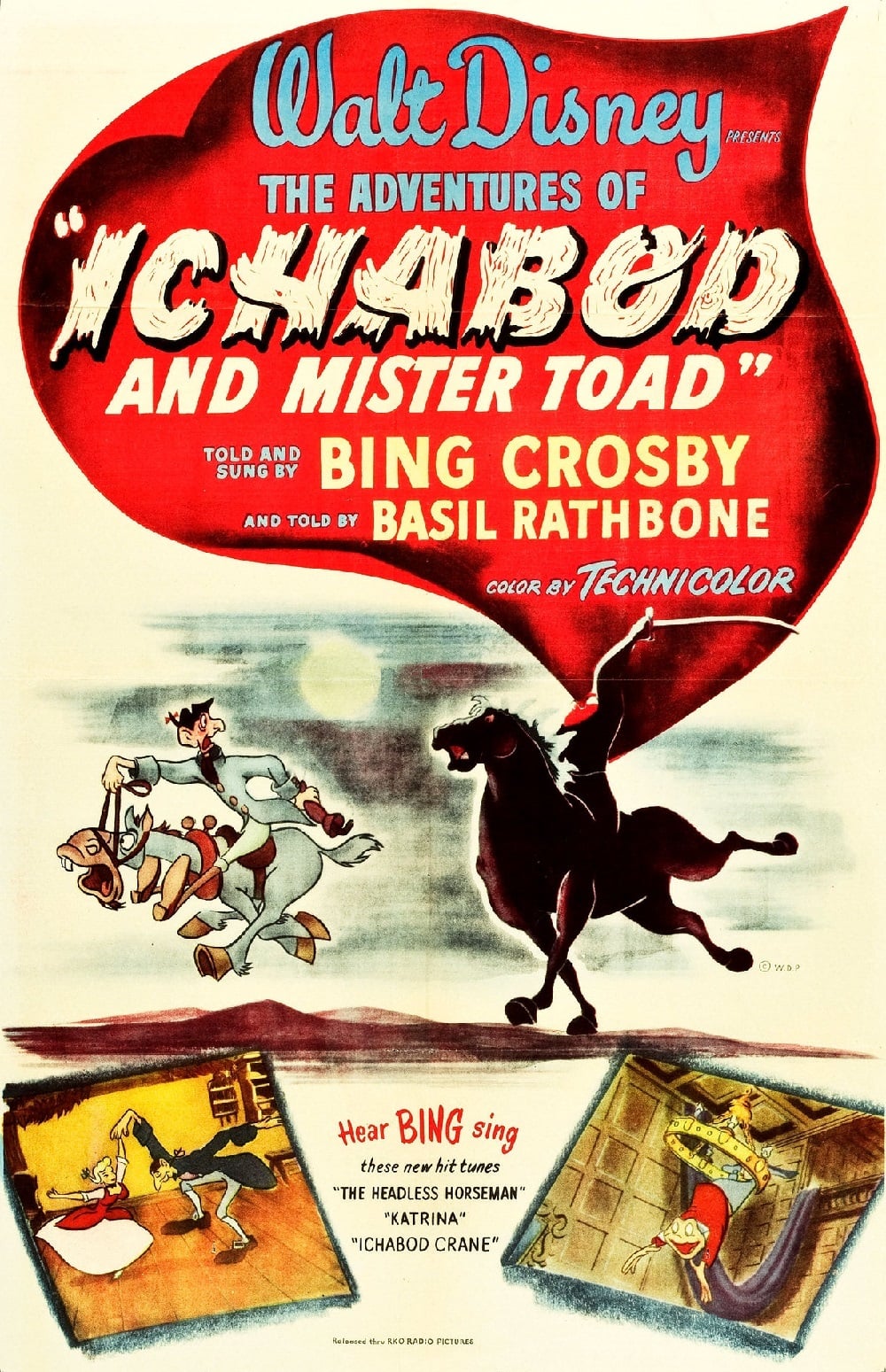

It is readily observed that there were six package films produced by the Disney Studios from 1942 to 1949, a desperate cost-saving measure in the years during and immediately following World War II. Not so obvious is the fact that these six films can be easily broken into three pairs: two Latin American goodwill efforts, two contemporary music anthologies, and two "double features" of stories that should have been proper feature-length efforts on their own, if only the company could have afforded to spend the time and money developing them. Least apparent of all - for it is largely a matter of taste - in each of these sets of two, the latter film was a marked improvement on the first. The Three Caballeros is infinitely better than Saludos Amigos, of course; Make Mine Music does not reach the highest heights of Melody Time, and while Fun and Fancy Free boasts a wholly credible second half, it is nowhere in the same league as The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, an exceedingly well-mounted movie that, outside of my rather personal enthusiasm for The Three Caballeros, makes a plausible argument for itself as the best of all the package films; the least we can say is that it certainly contains the single most famous short across all of the package films.

As with Fun and Fancy Free, Ichabod and Mr. Toad was initially designed as two movies: an adaptation of Kenneth Grahame's piss-taking of British social mores disguised as a playful story of anthropomorphic animals, The Wind in the Willows; and Washington Irving's famous Post-Revolutionary American ghost story The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. Now, I would posit that the two segments in Fun and Fancy Free do not suffer for being anthologised: nothing we see of "Bongo" makes me wish that it were any longer, while "Mickey and the Beanstalk" seems exactly as long as it has to be and no more. In contrast, both parts of Ichabod and Mr. Toad are so wonderful that it seems a damned shame that they weren't given more space to grow and develop - especially the Wind in the Willows half, which treats upon only a portion of the novel. But better by far that we get at least this minimal treatment of the stories than none at all.

The theme very loosely unifying the two halves of the film is "famously idiosyncratic literary figures", with a more official line being "literary characters who have tremendous jags of misfortune", although it must be said that Mr. Toad does much more to deserve his fate than Ichabod Crane. Still, it's a much likelier pairing than the vague suggestion that both "Bongo" and "Mickey and the Beanstalk" treat upon the idea of being optimistic and fancy-free. The film opens with a live-action tracking shot along the shelves of a library, as Basil Rathbone waxes rhapsodic about the many great figures in British literature; Robin Hood! people that I've never heard of! but his favorite is, of course, Sherlock Holmes. Although he claims that it's Mr. Toad of Toad Hall, Grahame's pleasant satire of rural landowners who run up enormous lines of credit on the family name, getting away with murder because they can plausibly claim to be The Right Kind of Person, and generally playing merry hell with the lives of everyone around them because they are Classy and Of Good Breeding.

Disney's treatment jettisons most of the novel's incident, leaving the following plot: at the beginning of the film, Toad has left his books in the care of Angus MacBadger (voiced by Disney storyman Campbell Grant), a crusty Scot who despairs of Toad's constant lack of maturity, along with Toad's friends Rat (Claude Allister) and Mole (Campbell Grant). Their concerns have all come to naught, though, for just at this time, Toad (played by Eric Blore, a very familiar name from the Astaire/Rogers cycle of musicals, in one of his last film roles; arguably the first celebrity casting in Disney history, if we can all agree that playing several memorable role in 1930s RKO musicals counts as "celebrity") has acquired a cart and a horse named Cyril (J. Pat O'Malley, who was not yet a celebrity, but after a few subsequent Disney pictures and a truly shocking number of TV guest appearances, would become a reasonably well-known character actor), and has taken to tearing his way across the countryside.

Things couldn't get any worse, until Toad finds a new love in the shiny motorcars just then making themselves felt on Britain's country roads, and before you can say "entitled moneyed classes", Toad has ended up on trial for grand theft auto. His clever defense, that he paid for the car with the deed to Toad Hall, while true is unconvincing, and he ends up in prison. Luckily, Cyril helps him bust out, just in time to save Toad Hall from the pack of weasels that have taken over, along with his three friends, all of whom are quite pleased when he decides that after taking back his ancestral manse and clearing his name, he'll turn over a new leaf and become a much saner, less spendthrift Toad. Do you believe that for a moment? Neither do I.

"The Wind in the Willows" has a significance beyond a great many Disney films better-known: it was the basis for Mr. Toad's Wild Ride, one of the opening-day Disneyland rides in 1955 (it also operated in Walt Disney World for 27 years, before its lamentable 1998 closure), and still one of the finest attractions in Fantasyland. But that has very little to do with anything, though it is a curious fact that literally millions of people have been on some version of that ride, compared to the much smaller number that have actually seen the featurette. A pity - a most lamentable pity! "The Wind in the Willows" is one of the most absolutely charming Disney productions of the immediate post-war years, and if I may be so bold, it's actually my favorite half of Ichabod and Mr. Toad. 33 minutes (almost exactly half of the 68-minute feature, less the opening credits) is just enough time to present the story with whirlwind speed, and so it is probably the fastest and most incident-heavy project the studio had made in a long time - since The Three Caballeros, I feel comfortable saying, though I haven't seen every last short they made during those years. With the maddeningly chipper, silly song "Nowhere in Particular" to lead it off, this is one of the few truly madcap Disney animations, and perhaps the only one made in the '40s where the increased emphasis on slapstick and absurdity didn't translate into making the film an essential rip-off of Warner's Looney Tunes. No, it's Disney through-and-through, but a loopier style of Disney would not be seen again until the 1960s.

I had not seen this film for some years prior to preparing for this review, and in my mind it was of much higher production quality than the other package films. Not so! "The Wind in the Willows" bears the same hallmarks as everything else post-Bambi: very simple character design, relatively simplistic backgrounds. No more money was being poured into this film than any other. What I have concluded is that my memory was not of the animation's "quality," but of its technical competence - which is considerable. This was a transitional film, in that the directing animators were sometimes assigned sequences, rather than characters - as had been the practice for most of the studio's history - and particular characters only in a few cases (mostly in the "Sleepy Hollow" segment). The sequences in "The Wind in the Willows" show all the grand mastery of the form that their animators had achieved in a decade or more working in Walt's dream factory. The two men of especial importance to "The Wind in the Willows" are Ollie Johnston, whose work on Toad's trial is of the most estimable quality; not exactly typical of his work, but the prosecuting attorney especially is a marvel of fluid motion and physical gestures. Wolfgang Reitherman was responsible for a lengthy, sublimely comic chase scene throughout Toad Hall, which was such a great success that he saw fit to re-use lengthy portions of the animation in The Jungle Book, which he directed some 18 years later. I do not of course mean to denigrate the magnificent work done by the other men who helped put this film together (Frank Thomas's character designs on Toad, Rat, and Mole deserve special notice): it has some of the most wonderful character animation of the 1940s, and even if it suffers in clear ways from the package film's characteristic cheapness, I cannot think of anyone who'd otherwise speak against it. If there's a more fun, active, and cartoony - in all the best senses of the word - Disney piece from the years 1945-1950, I have certainly not seen it.

After Rathbone takes us out of the Grahame story, whose voice should pop up but Bing Crosby, who admits that Toad is a pretty great character - but darn it, we Americans have some fine literature of our own. In a nifty, and possibly unintended segue, he proves his point by referring to arguably the earliest work of native-born U.S. literature that has any contemporary currency whatsoever, and proceeds the tells us "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" in a version that is to this day still the most definitive telling of that famous story - I don't doubt for an instant that more people have seen Disney's film in one or another of its various releases than have read Washington Irving's novella - I can name not just a couple people who consider viewing the Disney an absolute prerequisite to having a successful Halloween night.

Do I actually need to recap the story? Well, I will anyway: in the teeny little New York hamlet of Sleepy Hollow, there comes one day a new schoolmaster named Ichabod Crane, whose eduction impresses all the single ladies of the community - certainly, it's not his looks, as he resembles nothing so much as an ambulatory scarecrow, with his skinny limbs and woodcock head. And it's probably not his personality, either, since it seems that he's a bit of a gold digger, whose only appreciation of women lies in what they can give him. Especially if it's food. Or, in the case of the lovely Katrina Van Tassel, the keys to the wealthiest farm in the county. Standing between Ichabod and Katrina's hand, though, lies the town bully, Brom Bones, who suffers from a peculiar inability to best the schoolmaster in head-to-head contests, despite being infinitely stronger and more attractive.

All that changes on the night of October 31, when Baltus Van Tassel hosts his annual Halloween party, and Brom - knowing of Ichabod's crippling superstition, strikes back at the schoolmaster by telling the local legend of the Headless Horseman, who stalks about on that very evening every year, looking for a head to cut to replace his own. Well and truly freaked-out, Ichabod forces himself to journey on the miserable lonely ride home (which I've never understood - surely, someone else was leaving the party and had to go back to town?), through a nightmarish woodland hellscape, and it just so happens that this legend happens to be fact: and Ichabod's encounter with the Horseman means that one way or another, Sleepy Hollow is without a schoolmaster come November 1.

It is absolutely the case that the Disney story people did a top-notch job of telling Irving's story in 33 minutes so that it seems that hardly a beat was missed; unlike "The Wind in the Willows", you can't really say that the needed more time, unless it was by adding a strange X-Files-inflected plot about the local village elders and their conspiracy of silence, and Baltus Van Tassel's witchy wife.* It's just so damn good that you want more of it. It is told in the same manner as a number of shorts and anthology pieces before it: there are no character voices, only Crosby narrating and sometimes singing for one of the characters (aided by the girl vocal group The Rhythmaires). But it never feels as flat and depopulated as something like "Bongo"; the songs are pretty good throughout, and love him or not, Bing Crosby certainly had a rich, inviting voice.

I think, though, that just about everyone would agree that the biggest success of the piece is the design, especially of the moonlit forest where Ichabod has his fateful encounter: rarely has an animated movie achieved such a haunted, autumnal feeling, and even without the presence of the Headless Horseman, the sequence is undoubtedly creepy enough to put the film in the proud company of Disney movies that mess you up bad when you first see them as a small child. It's not only the forest, though: Sleepy Hollow itself has a lovely appearance that never betrays its origins as a cartoon, but manages anyway to capture the feeling of period paintings depicting the simple rural communities of the late 18th Century.

As far as the characters go, Ichabod Crane is essentially perfection: looking exactly as Irving described him, but he still seems enough like a human being - relative at least to the more typical humans populating the movie - that he's not simply grotesque. Credit once again to Ollie Johnston, the primary animator on Ichabod, though the nighttime forest scenes were done by John Lounsbery, another one of the great classic era Disney animators (he was responsible for the wolf in "Peter and the Wolf", just for starters). Johnston, it is usually said, had more to do with the actual design of the character; but both animate him tremendously well, though I must tip my hat more towards Lounsbery, and his masterful physical evocation of Ichabod's dread on the ride home. It is wonderfully comic while also being suspenseful - a neat trick to pull off.

The chase between Ichabod and the horseman was handled by Woolie Reitherman, making him the undisputed MVP of Ichabod and Mr. Toad - he's responsible for arguably the two best sequences in the movie, and if this latter nighttime chase in particular isn't the film's highlight, well then I just don't know what to say. Slapstick meeting horror in a truly brilliant mixture, it's the kind of thing that animation can do that live action simply cannot approach.

The only other truly great character animation in this half of the film is Brom, the antagonist (calling him a villain is a stretch); he's the work of Milt Kahl, who was one of the human specialists at Disney, if it's fair to say such at thing: his characters were masterpieces of well-observed movement and physicality, particularly his villains (though his two greatest creations, I think I can say without doubt, were both animals; bother tigers, in fact, though very different kinds of tigers they were...). Most of the supporting characters are fairly unengaging, and one in particular, a little round woman in green who lusts after Ichabod, is one of the more obnoxious female stereotypes of Disney in the '40s. Special attention must be paid to Katrina, perhaps the first example in a Disney feature of borrowed animation, or more specifically, borrowed design: she looks exactly like Grace Martin from "The Martins and the Coys" in Make Mine Music. In the hands of Ward Kimball, she has some evocative body language and facial expressions, but on the whole I think she's a stiff, obvious character who does nothing interesting; a rare disappointing effort from Kimball, who I'm usually happy to call my favorite of the Nine Old Men.

This sometimes limp character animation and design aside, there's not much to complain about in the visuals of "Sleepy Hollow", nor in Ichabod and Mr. Toad as a whole, which manages to succeed as a very technically accomplished piece of animation - the studio's best in some years - despite having a strapped budget. The reason, if I am not mistaken, is easy to pinpoint: the next film, already in development, was going to be a legitimate feature, with a real budget, and Ichabod and Mr. Toad was ultimately used as the stretching exercise ,if you will, for the animators to get used to working on something real and prestigious again. It limbered up their skills that hadn't been used, at this point, in something like seven years. The results obviously paid off in the long-term, but even in the short term, this is none too shabby a project: the most competently animated of all the package films, and for the Disney animators in their prime, mere competence was a surpassingly high mark.

*

*I tease, I actually really enjoy Tim Burton's Sleepy Hollow, as a masterpiece of design and cinematography if nothing else.

As with Fun and Fancy Free, Ichabod and Mr. Toad was initially designed as two movies: an adaptation of Kenneth Grahame's piss-taking of British social mores disguised as a playful story of anthropomorphic animals, The Wind in the Willows; and Washington Irving's famous Post-Revolutionary American ghost story The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. Now, I would posit that the two segments in Fun and Fancy Free do not suffer for being anthologised: nothing we see of "Bongo" makes me wish that it were any longer, while "Mickey and the Beanstalk" seems exactly as long as it has to be and no more. In contrast, both parts of Ichabod and Mr. Toad are so wonderful that it seems a damned shame that they weren't given more space to grow and develop - especially the Wind in the Willows half, which treats upon only a portion of the novel. But better by far that we get at least this minimal treatment of the stories than none at all.

The theme very loosely unifying the two halves of the film is "famously idiosyncratic literary figures", with a more official line being "literary characters who have tremendous jags of misfortune", although it must be said that Mr. Toad does much more to deserve his fate than Ichabod Crane. Still, it's a much likelier pairing than the vague suggestion that both "Bongo" and "Mickey and the Beanstalk" treat upon the idea of being optimistic and fancy-free. The film opens with a live-action tracking shot along the shelves of a library, as Basil Rathbone waxes rhapsodic about the many great figures in British literature; Robin Hood! people that I've never heard of! but his favorite is, of course, Sherlock Holmes. Although he claims that it's Mr. Toad of Toad Hall, Grahame's pleasant satire of rural landowners who run up enormous lines of credit on the family name, getting away with murder because they can plausibly claim to be The Right Kind of Person, and generally playing merry hell with the lives of everyone around them because they are Classy and Of Good Breeding.

Disney's treatment jettisons most of the novel's incident, leaving the following plot: at the beginning of the film, Toad has left his books in the care of Angus MacBadger (voiced by Disney storyman Campbell Grant), a crusty Scot who despairs of Toad's constant lack of maturity, along with Toad's friends Rat (Claude Allister) and Mole (Campbell Grant). Their concerns have all come to naught, though, for just at this time, Toad (played by Eric Blore, a very familiar name from the Astaire/Rogers cycle of musicals, in one of his last film roles; arguably the first celebrity casting in Disney history, if we can all agree that playing several memorable role in 1930s RKO musicals counts as "celebrity") has acquired a cart and a horse named Cyril (J. Pat O'Malley, who was not yet a celebrity, but after a few subsequent Disney pictures and a truly shocking number of TV guest appearances, would become a reasonably well-known character actor), and has taken to tearing his way across the countryside.

Things couldn't get any worse, until Toad finds a new love in the shiny motorcars just then making themselves felt on Britain's country roads, and before you can say "entitled moneyed classes", Toad has ended up on trial for grand theft auto. His clever defense, that he paid for the car with the deed to Toad Hall, while true is unconvincing, and he ends up in prison. Luckily, Cyril helps him bust out, just in time to save Toad Hall from the pack of weasels that have taken over, along with his three friends, all of whom are quite pleased when he decides that after taking back his ancestral manse and clearing his name, he'll turn over a new leaf and become a much saner, less spendthrift Toad. Do you believe that for a moment? Neither do I.

"The Wind in the Willows" has a significance beyond a great many Disney films better-known: it was the basis for Mr. Toad's Wild Ride, one of the opening-day Disneyland rides in 1955 (it also operated in Walt Disney World for 27 years, before its lamentable 1998 closure), and still one of the finest attractions in Fantasyland. But that has very little to do with anything, though it is a curious fact that literally millions of people have been on some version of that ride, compared to the much smaller number that have actually seen the featurette. A pity - a most lamentable pity! "The Wind in the Willows" is one of the most absolutely charming Disney productions of the immediate post-war years, and if I may be so bold, it's actually my favorite half of Ichabod and Mr. Toad. 33 minutes (almost exactly half of the 68-minute feature, less the opening credits) is just enough time to present the story with whirlwind speed, and so it is probably the fastest and most incident-heavy project the studio had made in a long time - since The Three Caballeros, I feel comfortable saying, though I haven't seen every last short they made during those years. With the maddeningly chipper, silly song "Nowhere in Particular" to lead it off, this is one of the few truly madcap Disney animations, and perhaps the only one made in the '40s where the increased emphasis on slapstick and absurdity didn't translate into making the film an essential rip-off of Warner's Looney Tunes. No, it's Disney through-and-through, but a loopier style of Disney would not be seen again until the 1960s.

I had not seen this film for some years prior to preparing for this review, and in my mind it was of much higher production quality than the other package films. Not so! "The Wind in the Willows" bears the same hallmarks as everything else post-Bambi: very simple character design, relatively simplistic backgrounds. No more money was being poured into this film than any other. What I have concluded is that my memory was not of the animation's "quality," but of its technical competence - which is considerable. This was a transitional film, in that the directing animators were sometimes assigned sequences, rather than characters - as had been the practice for most of the studio's history - and particular characters only in a few cases (mostly in the "Sleepy Hollow" segment). The sequences in "The Wind in the Willows" show all the grand mastery of the form that their animators had achieved in a decade or more working in Walt's dream factory. The two men of especial importance to "The Wind in the Willows" are Ollie Johnston, whose work on Toad's trial is of the most estimable quality; not exactly typical of his work, but the prosecuting attorney especially is a marvel of fluid motion and physical gestures. Wolfgang Reitherman was responsible for a lengthy, sublimely comic chase scene throughout Toad Hall, which was such a great success that he saw fit to re-use lengthy portions of the animation in The Jungle Book, which he directed some 18 years later. I do not of course mean to denigrate the magnificent work done by the other men who helped put this film together (Frank Thomas's character designs on Toad, Rat, and Mole deserve special notice): it has some of the most wonderful character animation of the 1940s, and even if it suffers in clear ways from the package film's characteristic cheapness, I cannot think of anyone who'd otherwise speak against it. If there's a more fun, active, and cartoony - in all the best senses of the word - Disney piece from the years 1945-1950, I have certainly not seen it.

After Rathbone takes us out of the Grahame story, whose voice should pop up but Bing Crosby, who admits that Toad is a pretty great character - but darn it, we Americans have some fine literature of our own. In a nifty, and possibly unintended segue, he proves his point by referring to arguably the earliest work of native-born U.S. literature that has any contemporary currency whatsoever, and proceeds the tells us "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" in a version that is to this day still the most definitive telling of that famous story - I don't doubt for an instant that more people have seen Disney's film in one or another of its various releases than have read Washington Irving's novella - I can name not just a couple people who consider viewing the Disney an absolute prerequisite to having a successful Halloween night.

Do I actually need to recap the story? Well, I will anyway: in the teeny little New York hamlet of Sleepy Hollow, there comes one day a new schoolmaster named Ichabod Crane, whose eduction impresses all the single ladies of the community - certainly, it's not his looks, as he resembles nothing so much as an ambulatory scarecrow, with his skinny limbs and woodcock head. And it's probably not his personality, either, since it seems that he's a bit of a gold digger, whose only appreciation of women lies in what they can give him. Especially if it's food. Or, in the case of the lovely Katrina Van Tassel, the keys to the wealthiest farm in the county. Standing between Ichabod and Katrina's hand, though, lies the town bully, Brom Bones, who suffers from a peculiar inability to best the schoolmaster in head-to-head contests, despite being infinitely stronger and more attractive.

All that changes on the night of October 31, when Baltus Van Tassel hosts his annual Halloween party, and Brom - knowing of Ichabod's crippling superstition, strikes back at the schoolmaster by telling the local legend of the Headless Horseman, who stalks about on that very evening every year, looking for a head to cut to replace his own. Well and truly freaked-out, Ichabod forces himself to journey on the miserable lonely ride home (which I've never understood - surely, someone else was leaving the party and had to go back to town?), through a nightmarish woodland hellscape, and it just so happens that this legend happens to be fact: and Ichabod's encounter with the Horseman means that one way or another, Sleepy Hollow is without a schoolmaster come November 1.

It is absolutely the case that the Disney story people did a top-notch job of telling Irving's story in 33 minutes so that it seems that hardly a beat was missed; unlike "The Wind in the Willows", you can't really say that the needed more time, unless it was by adding a strange X-Files-inflected plot about the local village elders and their conspiracy of silence, and Baltus Van Tassel's witchy wife.* It's just so damn good that you want more of it. It is told in the same manner as a number of shorts and anthology pieces before it: there are no character voices, only Crosby narrating and sometimes singing for one of the characters (aided by the girl vocal group The Rhythmaires). But it never feels as flat and depopulated as something like "Bongo"; the songs are pretty good throughout, and love him or not, Bing Crosby certainly had a rich, inviting voice.

I think, though, that just about everyone would agree that the biggest success of the piece is the design, especially of the moonlit forest where Ichabod has his fateful encounter: rarely has an animated movie achieved such a haunted, autumnal feeling, and even without the presence of the Headless Horseman, the sequence is undoubtedly creepy enough to put the film in the proud company of Disney movies that mess you up bad when you first see them as a small child. It's not only the forest, though: Sleepy Hollow itself has a lovely appearance that never betrays its origins as a cartoon, but manages anyway to capture the feeling of period paintings depicting the simple rural communities of the late 18th Century.

As far as the characters go, Ichabod Crane is essentially perfection: looking exactly as Irving described him, but he still seems enough like a human being - relative at least to the more typical humans populating the movie - that he's not simply grotesque. Credit once again to Ollie Johnston, the primary animator on Ichabod, though the nighttime forest scenes were done by John Lounsbery, another one of the great classic era Disney animators (he was responsible for the wolf in "Peter and the Wolf", just for starters). Johnston, it is usually said, had more to do with the actual design of the character; but both animate him tremendously well, though I must tip my hat more towards Lounsbery, and his masterful physical evocation of Ichabod's dread on the ride home. It is wonderfully comic while also being suspenseful - a neat trick to pull off.

The chase between Ichabod and the horseman was handled by Woolie Reitherman, making him the undisputed MVP of Ichabod and Mr. Toad - he's responsible for arguably the two best sequences in the movie, and if this latter nighttime chase in particular isn't the film's highlight, well then I just don't know what to say. Slapstick meeting horror in a truly brilliant mixture, it's the kind of thing that animation can do that live action simply cannot approach.

The only other truly great character animation in this half of the film is Brom, the antagonist (calling him a villain is a stretch); he's the work of Milt Kahl, who was one of the human specialists at Disney, if it's fair to say such at thing: his characters were masterpieces of well-observed movement and physicality, particularly his villains (though his two greatest creations, I think I can say without doubt, were both animals; bother tigers, in fact, though very different kinds of tigers they were...). Most of the supporting characters are fairly unengaging, and one in particular, a little round woman in green who lusts after Ichabod, is one of the more obnoxious female stereotypes of Disney in the '40s. Special attention must be paid to Katrina, perhaps the first example in a Disney feature of borrowed animation, or more specifically, borrowed design: she looks exactly like Grace Martin from "The Martins and the Coys" in Make Mine Music. In the hands of Ward Kimball, she has some evocative body language and facial expressions, but on the whole I think she's a stiff, obvious character who does nothing interesting; a rare disappointing effort from Kimball, who I'm usually happy to call my favorite of the Nine Old Men.

This sometimes limp character animation and design aside, there's not much to complain about in the visuals of "Sleepy Hollow", nor in Ichabod and Mr. Toad as a whole, which manages to succeed as a very technically accomplished piece of animation - the studio's best in some years - despite having a strapped budget. The reason, if I am not mistaken, is easy to pinpoint: the next film, already in development, was going to be a legitimate feature, with a real budget, and Ichabod and Mr. Toad was ultimately used as the stretching exercise ,if you will, for the animators to get used to working on something real and prestigious again. It limbered up their skills that hadn't been used, at this point, in something like seven years. The results obviously paid off in the long-term, but even in the short term, this is none too shabby a project: the most competently animated of all the package films, and for the Disney animators in their prime, mere competence was a surpassingly high mark.

*

*I tease, I actually really enjoy Tim Burton's Sleepy Hollow, as a masterpiece of design and cinematography if nothing else.