Universal Horror: A new world of gods and monsters

The massive success of 1931's twin gods, Dracula and Frankenstein, left no doubt that Universal Pictures was Hollywood's home for terror and the paranormal, and the studio flung itself into the burgeoning new genre with glee, whatever lingering moral qualms Carl Laemmle, Sr. might still have nursed. The next two years bore witness to the next pair of the studio's iconic monsters in The Mummy and The Invisible Man; I will not at this time be jumping into a consideration of those two franchises, but will instead skip ahead to 1935, when Universal first tasted the sweet fruit of the sequel tree.

It's easy enough to look around and assume that there have never been so many sequels as plague us in the modern day, and it's true that sequels have never before enjoyed so much box-office clout as they do now. But the Golden Age of the Sequel is not the 2000s, nor was it the 1980s, when every crap movie that could be made for under $15 million was later remade for $10 million with the number "2" stuck to the title. Believe it or not, the sequel was just as robust in the 1930s and 1940s as it is today; only most of those films have been lost to history, sucking just as much as the modern sequel but without the built-in audience generator of cable TV and home video.

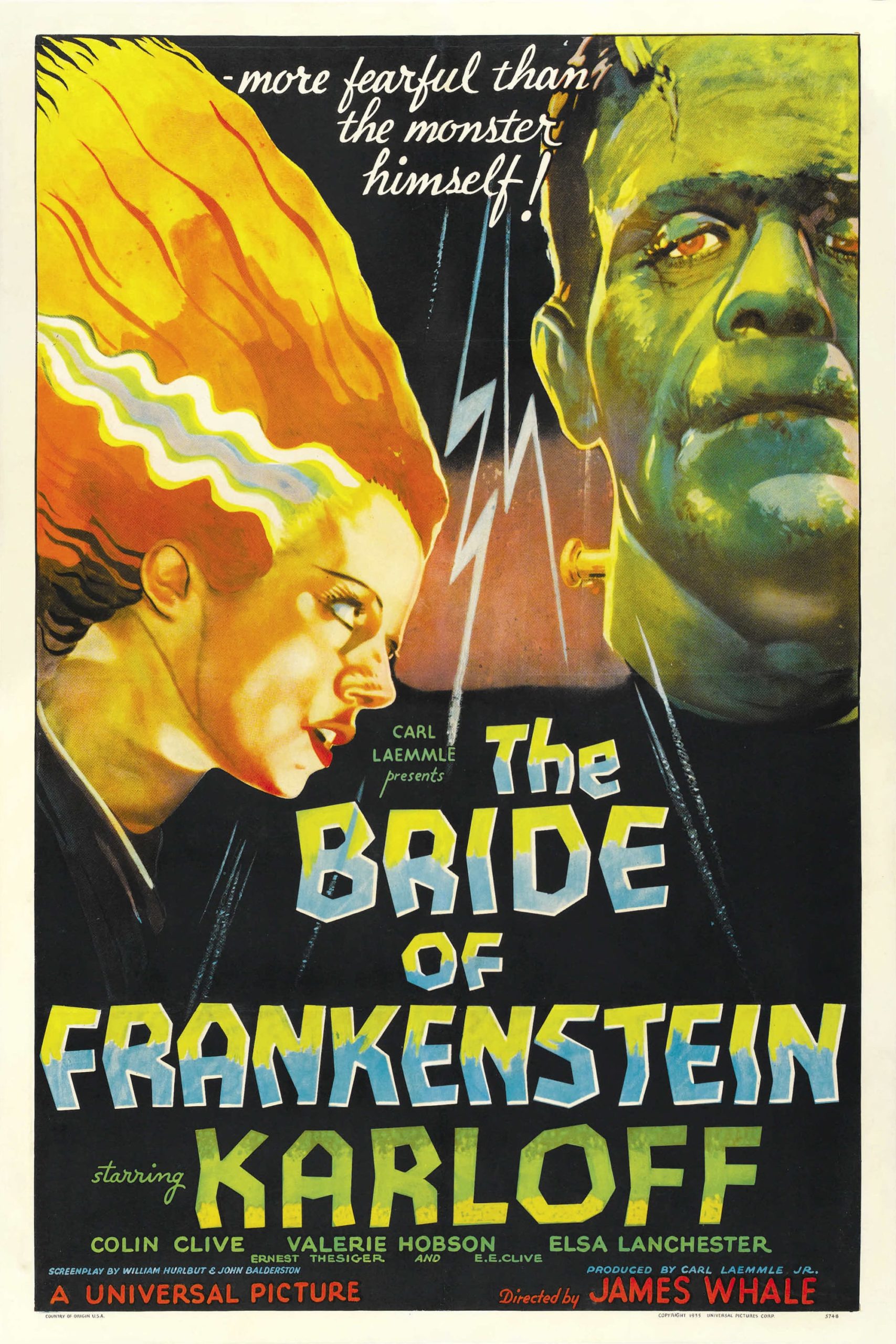

I do not know where exactly this sequel boom began; I only know that Universal had been trying to put together follow-ups to its two big horror smashes for some years when James Whale finally agreed to make a second Frankenstein on the single condition that he get to make whatever the hell movie he wanted, as far as the censors would allow, of course. He got his wish, and in the spring of 1935 the world was graced with Bride of Frankenstein, one of history's few sequels that is nearly universally regarded as an improvement over its very successful predecessor, and perhaps the first example of a subgenre that would later come to plague the cinema with just as much intensity as the sequel, although in a much smaller sphere: the horror-comedy.

Yes! that is what James Whale did with his new-found free hand, and for this let us never stop singing his name as one of the truly essential American directors of the 1930s. Bride of Frankenstein is still a little bit unlike anything else out there, and in '35 it must have seemed like a bomb going off in every theater where it played. This was years before the concept of "camp" had come anywhere near the mainstream, and yet here it was, American cinema's first bona-fide camp classic (it cannot possibly be an accident that James Whale was also American cinema's first openly gay filmmaker). And so it remains today, a film in which the Expressionist style of the first Frankenstein runs galloping into the feverishly over-the-top performances of Ernest Thesiger and a newly inspired Colin Clive, with a healthy sprinkling of some of the weirdest comic relief in any horror movie of that whole generation. This collision produced no less than a masterpiece; if Frankenstein is a great Hollywood film of the 1930s, well, Bride of Frankenstein is one of the very best Hollywood films of the 1930s.

It opens with one of the oddest little scenes in horror film history. The camera tracks towards a model of a creepy old house on a hill in a thunderstorm (we're not to the odd part yet), and just when we expect to find Dr. Frankenstein's laboratory waiting for us, we end up in a very pleasant parlor in 1816 or thereabouts, where Lord Byron (Gavin Gordon), Percy Bysshe Shelley (Douglas Walton) and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (Elsa Lanchester) are having a conversation about the recent night when Mary shared with the other two (and Byron's rumored lover John Polidori, who seems to have been Hayes Office'd right out of the movie) her bloodcurdling tale of horror, Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. Byron is particularly enthusiastic about the story, despite Mary's protestations that it's too dark and grim a night for such horrors, and he takes some time recall his favorite moments from the text - that is to say, he recaps the events of the first film for those of us in the audience who haven't seen it recently, or at all. If only there were more to the story, he muses. And Mary coyly mentions that, since he mentions it...

I am, truly, in awe of that scene. For one thing, it's a fairly clever way of getting the obligatory sequel recap out of the way, and while I kind of wish that Whale hadn't seen fit to use the actual footage from Frankenstein, this is a problem that is rarely or indeed never solved to complete satisfaction. More importantly, this is a horror film where Lord Byron and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley are just hanging out and talking about the movie we're about to see. It's such a bizarre way to start up a film, and far too post-modern for 1935, but hey, if Whale was going to introduce the world to camp, he might as well introduce the world to post-modernism at the same time.

Anyway, the story that follows is actually a touch closer to the original, fairly unreadable novel than the first movie actually was, but we're not going to hold that against it. It seems that the end of the last film was a hideous lie: actually, Dr. Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive) was thrown from the burning windmill by his creation (the absolutely irreplaceable Boris Karloff), just as the whole structure collapsed. Frankenstein survived, barely, but the monster appears to have died in the conflagration.

Except then there'd be little point to the movie. What actually happened is that the monster fell into a subterranean pool of water beneath the mill, and thus survived the flames. He is discovered by an unfortunate pair of peasants (Reginald Barlow and Mary Gordon) who wanted to make sure that the fiend who killed their darling Maria - the drowned girl from last time - is actually gone; no, as it turns out, and they both get a watery doom for their trouble. Confused and angry, the creature goes storming out into the woods, to hide from the mob of villagers that has already learned of his survival.

Meanwhile, Frankenstein is healing nicely from his wounds under the loving care of his fiancée Elizabeth (Valerie Hobson, a much better fit for the role than the wooden Mae Clarke), when he gets an unexpected visitor: his old professor, Dr. Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger). We quickly learn that, where Frankenstein has some crazy ideas and a God complex, Pretorius is a full-blown "race of super-people" Mad Scientist, harboring the same kind of outrageous theories as Frankenstein, but going about them in a far less scientifically pure manner. For one thing, what he does verges on black magic, in Frankenstein's eyes: creating life from nothing, rather than creating life from death. For another, the only thing he's been able to do so far is make a small menagerie of homunculi, nothing remotely as impressive as the lumbering patchwork corpse presently stomping around outside Goldstadt. When Pretorius suggests that the two men combine their knowledge, Frankenstein (suitably chastened from the last film) refuses, horrified.

But what about that monster lumbering around the woods? Besides scaring some defenseless villagers, completely without meaning to, he manages to find himself in the hut of a blind old hermit (O.P. Heggie). Something very unexpected happens in that little building: the creature starts to learn what it is to be human. The hermit teaches him a small vocabulary, and things seem quite nice and peaceful; it lasts for barely any time at all, when those hunters show up and the creature has to escape to a nearby crypt. There he stumbles across Pretorius, stealing bones to make his newest creation, and the net result is that Elizabeth gets abducted, and the only way that her new husband can save her is to help Pretorius build a new, better, female creature: the bride of Frankenstein!

And so much fun does Thesiger have when he says that line, after the bride is given life in an even glitzier effects showcase than in the first film, I should like to offer him a few more exclamation points: the bride of Frankenstein!!!!!!

!!

By all rights, the film's intense tonal shifts should not work at all. Let's take a look: we've got the broadest kind of '30s humor in the form of Frankenstein's housekeeper Minnie (Una O'Connor); the high camp preening of Thesiger as Pretorius, followed at a slight distance by Clive in sort of "medium camp" mode; and then on the other side, the creature, played by Karloff in the single best performance of a career that is fuller of great acting than you'd probably expect, gets a full range of fascinating, beautiful emotions. It's tempting just to quote some of his most iconic lines, and let the memory of Karloff's perfect mix of pain, joy, anger, confusion, and the rest flicker through the reader's mind: "Alone bad, friend good"; "I love dead. Hate living"; "We belong dead". But then I run the risk of the reader not having actually seen the movie. So let's just go with this instead: it is the most heartbreaking and sincere character development in the entire history of horror cinema.

And to top it all off, Whale (now working with cinematographer John J. Mescall) hasn't really eased up on the profoundly harsh look of the franchise, still owing that debt to the German Expressionists, still among the most distinctive looking American horror films of all time. For my tastes, Bride of Frankenstein isn't quite as impressive to look at as Frankenstein; though the shadows and contrast are still there, the film isn't composed using such perfect geometry as the first one, strict geometrical composition being a key element of the Expressionist style. On the other hand, the first film doesn't have anything that can compare to the adventurous and amazing use of canted angles in the female creature's birth scene - another Expressionist trick, and one used wonderfully by Whale here. I should mention, to the side of all this, that the female creature's first appearance is presented exactly the same way that Karloff's creature was in the first film: a series of quick cuts jumping closer to its face. Simple, terribly effective - let us not blame Whale for not wishing to re-invent the wheel.

And speaking of the female creature, played by Elsa Lanchester in a rather different register than she played Mary Shelley, she adds something to Bride of Frankenstein that the original film sorely lacks: a genuinely creepy element. I'm sure much of that is because Karloff's presence as the monster has become so incredibly famous in the last seven decades that he simply doesn't have the power to shock anymore. But when Lanchester darts her head around like a bird, with those giant, unblinking eyes, it freaks me out just a tiny bit. Not as much as the creepiest parts of Dracula, and when all is said and done, we're talking about a film from the '30s, but... we're talking a film from the '30s. That it could be creepy in even a small way says a great deal.

So we've got horror, farce, Expressionism, camp, humanism: like I was saying, all these mashed-up tones shouldn't work at all. And yet, for some reason, it all does. Bride of Frankenstein really doesn't miss a beat. Re-watching it with an eye towards picking out all the flaws I could, there were only two: Una O'Connor can test the endurance even of a dedicated fan of 1930s humor; and the way the plot clumps into a Frankenstein segment, a creature segment, and then the finale, this is an inelegant structure that should have perhaps been cross-cut a bit - storytelling was much more sophisticated than that in 1935. But those are literally the only complaints I could come up with. Whatever James Whale did - and no matter how many times I've seen it, I still can't figure out what this movie's X-factor is - he did it spectacularly right.

This was to be his last horror film. Small wonder; what could he possibly have left to prove?

Reviews in this series

Frankenstein (Whale, 1931)

Bride of Frankenstein (Whale, 1935)

Son of Frankenstein (Lee, 1939)

The Ghost of Frankenstein (Kenton, 1942)

Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (Neill, 1943)

House of Frankenstein (Kenton, 1944)

House of Dracula (Kenton, 1945)

Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (Barton, 1948)

It's easy enough to look around and assume that there have never been so many sequels as plague us in the modern day, and it's true that sequels have never before enjoyed so much box-office clout as they do now. But the Golden Age of the Sequel is not the 2000s, nor was it the 1980s, when every crap movie that could be made for under $15 million was later remade for $10 million with the number "2" stuck to the title. Believe it or not, the sequel was just as robust in the 1930s and 1940s as it is today; only most of those films have been lost to history, sucking just as much as the modern sequel but without the built-in audience generator of cable TV and home video.

I do not know where exactly this sequel boom began; I only know that Universal had been trying to put together follow-ups to its two big horror smashes for some years when James Whale finally agreed to make a second Frankenstein on the single condition that he get to make whatever the hell movie he wanted, as far as the censors would allow, of course. He got his wish, and in the spring of 1935 the world was graced with Bride of Frankenstein, one of history's few sequels that is nearly universally regarded as an improvement over its very successful predecessor, and perhaps the first example of a subgenre that would later come to plague the cinema with just as much intensity as the sequel, although in a much smaller sphere: the horror-comedy.

Yes! that is what James Whale did with his new-found free hand, and for this let us never stop singing his name as one of the truly essential American directors of the 1930s. Bride of Frankenstein is still a little bit unlike anything else out there, and in '35 it must have seemed like a bomb going off in every theater where it played. This was years before the concept of "camp" had come anywhere near the mainstream, and yet here it was, American cinema's first bona-fide camp classic (it cannot possibly be an accident that James Whale was also American cinema's first openly gay filmmaker). And so it remains today, a film in which the Expressionist style of the first Frankenstein runs galloping into the feverishly over-the-top performances of Ernest Thesiger and a newly inspired Colin Clive, with a healthy sprinkling of some of the weirdest comic relief in any horror movie of that whole generation. This collision produced no less than a masterpiece; if Frankenstein is a great Hollywood film of the 1930s, well, Bride of Frankenstein is one of the very best Hollywood films of the 1930s.

It opens with one of the oddest little scenes in horror film history. The camera tracks towards a model of a creepy old house on a hill in a thunderstorm (we're not to the odd part yet), and just when we expect to find Dr. Frankenstein's laboratory waiting for us, we end up in a very pleasant parlor in 1816 or thereabouts, where Lord Byron (Gavin Gordon), Percy Bysshe Shelley (Douglas Walton) and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (Elsa Lanchester) are having a conversation about the recent night when Mary shared with the other two (and Byron's rumored lover John Polidori, who seems to have been Hayes Office'd right out of the movie) her bloodcurdling tale of horror, Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. Byron is particularly enthusiastic about the story, despite Mary's protestations that it's too dark and grim a night for such horrors, and he takes some time recall his favorite moments from the text - that is to say, he recaps the events of the first film for those of us in the audience who haven't seen it recently, or at all. If only there were more to the story, he muses. And Mary coyly mentions that, since he mentions it...

I am, truly, in awe of that scene. For one thing, it's a fairly clever way of getting the obligatory sequel recap out of the way, and while I kind of wish that Whale hadn't seen fit to use the actual footage from Frankenstein, this is a problem that is rarely or indeed never solved to complete satisfaction. More importantly, this is a horror film where Lord Byron and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley are just hanging out and talking about the movie we're about to see. It's such a bizarre way to start up a film, and far too post-modern for 1935, but hey, if Whale was going to introduce the world to camp, he might as well introduce the world to post-modernism at the same time.

Anyway, the story that follows is actually a touch closer to the original, fairly unreadable novel than the first movie actually was, but we're not going to hold that against it. It seems that the end of the last film was a hideous lie: actually, Dr. Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive) was thrown from the burning windmill by his creation (the absolutely irreplaceable Boris Karloff), just as the whole structure collapsed. Frankenstein survived, barely, but the monster appears to have died in the conflagration.

Except then there'd be little point to the movie. What actually happened is that the monster fell into a subterranean pool of water beneath the mill, and thus survived the flames. He is discovered by an unfortunate pair of peasants (Reginald Barlow and Mary Gordon) who wanted to make sure that the fiend who killed their darling Maria - the drowned girl from last time - is actually gone; no, as it turns out, and they both get a watery doom for their trouble. Confused and angry, the creature goes storming out into the woods, to hide from the mob of villagers that has already learned of his survival.

Meanwhile, Frankenstein is healing nicely from his wounds under the loving care of his fiancée Elizabeth (Valerie Hobson, a much better fit for the role than the wooden Mae Clarke), when he gets an unexpected visitor: his old professor, Dr. Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger). We quickly learn that, where Frankenstein has some crazy ideas and a God complex, Pretorius is a full-blown "race of super-people" Mad Scientist, harboring the same kind of outrageous theories as Frankenstein, but going about them in a far less scientifically pure manner. For one thing, what he does verges on black magic, in Frankenstein's eyes: creating life from nothing, rather than creating life from death. For another, the only thing he's been able to do so far is make a small menagerie of homunculi, nothing remotely as impressive as the lumbering patchwork corpse presently stomping around outside Goldstadt. When Pretorius suggests that the two men combine their knowledge, Frankenstein (suitably chastened from the last film) refuses, horrified.

But what about that monster lumbering around the woods? Besides scaring some defenseless villagers, completely without meaning to, he manages to find himself in the hut of a blind old hermit (O.P. Heggie). Something very unexpected happens in that little building: the creature starts to learn what it is to be human. The hermit teaches him a small vocabulary, and things seem quite nice and peaceful; it lasts for barely any time at all, when those hunters show up and the creature has to escape to a nearby crypt. There he stumbles across Pretorius, stealing bones to make his newest creation, and the net result is that Elizabeth gets abducted, and the only way that her new husband can save her is to help Pretorius build a new, better, female creature: the bride of Frankenstein!

And so much fun does Thesiger have when he says that line, after the bride is given life in an even glitzier effects showcase than in the first film, I should like to offer him a few more exclamation points: the bride of Frankenstein!!!!!!

!!

By all rights, the film's intense tonal shifts should not work at all. Let's take a look: we've got the broadest kind of '30s humor in the form of Frankenstein's housekeeper Minnie (Una O'Connor); the high camp preening of Thesiger as Pretorius, followed at a slight distance by Clive in sort of "medium camp" mode; and then on the other side, the creature, played by Karloff in the single best performance of a career that is fuller of great acting than you'd probably expect, gets a full range of fascinating, beautiful emotions. It's tempting just to quote some of his most iconic lines, and let the memory of Karloff's perfect mix of pain, joy, anger, confusion, and the rest flicker through the reader's mind: "Alone bad, friend good"; "I love dead. Hate living"; "We belong dead". But then I run the risk of the reader not having actually seen the movie. So let's just go with this instead: it is the most heartbreaking and sincere character development in the entire history of horror cinema.

And to top it all off, Whale (now working with cinematographer John J. Mescall) hasn't really eased up on the profoundly harsh look of the franchise, still owing that debt to the German Expressionists, still among the most distinctive looking American horror films of all time. For my tastes, Bride of Frankenstein isn't quite as impressive to look at as Frankenstein; though the shadows and contrast are still there, the film isn't composed using such perfect geometry as the first one, strict geometrical composition being a key element of the Expressionist style. On the other hand, the first film doesn't have anything that can compare to the adventurous and amazing use of canted angles in the female creature's birth scene - another Expressionist trick, and one used wonderfully by Whale here. I should mention, to the side of all this, that the female creature's first appearance is presented exactly the same way that Karloff's creature was in the first film: a series of quick cuts jumping closer to its face. Simple, terribly effective - let us not blame Whale for not wishing to re-invent the wheel.

And speaking of the female creature, played by Elsa Lanchester in a rather different register than she played Mary Shelley, she adds something to Bride of Frankenstein that the original film sorely lacks: a genuinely creepy element. I'm sure much of that is because Karloff's presence as the monster has become so incredibly famous in the last seven decades that he simply doesn't have the power to shock anymore. But when Lanchester darts her head around like a bird, with those giant, unblinking eyes, it freaks me out just a tiny bit. Not as much as the creepiest parts of Dracula, and when all is said and done, we're talking about a film from the '30s, but... we're talking a film from the '30s. That it could be creepy in even a small way says a great deal.

So we've got horror, farce, Expressionism, camp, humanism: like I was saying, all these mashed-up tones shouldn't work at all. And yet, for some reason, it all does. Bride of Frankenstein really doesn't miss a beat. Re-watching it with an eye towards picking out all the flaws I could, there were only two: Una O'Connor can test the endurance even of a dedicated fan of 1930s humor; and the way the plot clumps into a Frankenstein segment, a creature segment, and then the finale, this is an inelegant structure that should have perhaps been cross-cut a bit - storytelling was much more sophisticated than that in 1935. But those are literally the only complaints I could come up with. Whatever James Whale did - and no matter how many times I've seen it, I still can't figure out what this movie's X-factor is - he did it spectacularly right.

This was to be his last horror film. Small wonder; what could he possibly have left to prove?

Reviews in this series

Frankenstein (Whale, 1931)

Bride of Frankenstein (Whale, 1935)

Son of Frankenstein (Lee, 1939)

The Ghost of Frankenstein (Kenton, 1942)

Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (Neill, 1943)

House of Frankenstein (Kenton, 1944)

House of Dracula (Kenton, 1945)

Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (Barton, 1948)