The films of Alan J. Pakula

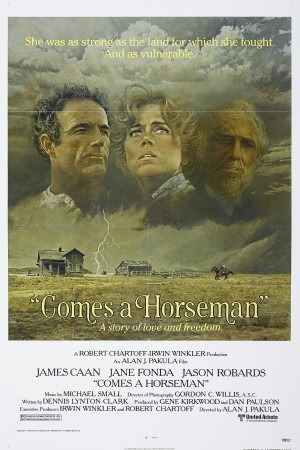

With his brace of mid-'70s paranoia epics out of his system, Alan J. Pakula's career settled back into a much more characteristic mode when he made his fifth feature two years after the critical and commercial triumph of All the President's Men. 1978's Comes a Horseman would prove to be a fairly intimate, domestic story about conflicting psychology in a stressful situation, the main character was a woman, the chief vehicle by which she processed her stress was by falling into a sexual relationship with a man, and the whole thing is one of the most peculiar neo-Westerns I've ever seen. Okay, so that last part isn't typical of Pakula. But in 1978, flat-out Westerns weren't typical of anybody (there were one or two a year throughout the decade), and lest we forget, this was about the same time that the grand experiment of the New Hollywood Cinema took its first decisive, damning swerve into "indulgent auteurs making absolutely fascinating movies that are kind of wrecks, when you get right down to it". Compared to a lot of the splashiest bombs of the era, Comes a Horseman isn't so terribly outrageous - Lord knows it's no New York, New York, a film that I love even as I recognise how many miles lie between itself and flawless - but hindsight tells us that it wasn't a terribly smart place for Robert Chartoff and Irwin Winkler to sink a lot of money. Of course, hindsight also knows that the mesmerising, unclassifiable money pit Heaven's Gate was just around the bend, so hindsight is pretty much treating any and all Westerns with the grave respect due to a snarling Rottweiler. At any rate, Comes a Horseman came out and made a wee bit of a splash, largely on the basis of its super A-list cast, and promptly sank into an obscurity that seems unreasonable for the next film by the man who'd just given the world All the President's Men and The Parallax View. I would at this point be a dick and say "unreasonable until you've seen it! phew, what a stinker!" except that Comes a Horseman really isn't all that bad: thanks to a surreally misjudged third act, it's definitely not all that good, either, but as an example of what a strong director and a top-tier cinematographer (Gordon Willis, naturally) could do when you set them loose on a Western, sheer novelty is enough to keep it more interesting than its non-existent reputation would indicate.

We'll learn a lot more about the setting as the film goes on, but here's where things start: Ella Connors (Jane Fonda) has just buried her father and assumed control of his fading cattle ranch, and she is almost immediately assailed by her former flame, J.W. Ewing (Jason Robards), who is a greedy cattleman typical of these kinds of films. Ella and her trusty ranch hand Dodger (Richard Farnsworth) will have none of it, and it seems that J.W. has another enemy in the area, a certain Frank Athearn (James Caan). It makes sense for Frank and Ella to team up, at least initially; and then it makes sense for them to team up some more, and eventually they start to fall in love a little bit, although it takes more than an hour of movie and about one year of ranching for them to figure out that last part.

It is often said that this first screenplay by Dennis Lynton Clark - perhaps you know his production design work in A Man Called Horse? - is largely responsible for Comes a Horseman being a crashing bore, because he filled it up with one soggy stereotype after another and then made the whole thing take about three times as long as it had to. The conventional wisdom has a point: the screenplay is none too imaginative, and very little happens. But to jump straightaway to "the film is a bore" is a bit of a leap. For a start, this is a film in which Gordon Willis gets to set hisself to the task of capturing the wide open grandeur of the Colorado Rockies (standing in for Arizona), using all the tricks of his trade. There might well be a world in which "Gordon Willis shoots a Western" is boring. I do not reside in that world.

Setting that aside as just one man's raving cinematographer crush, the story in Comes a Horseman isn't exactly the life-sucking blight that some might call it. Yes, it is a slow piece; ten and fifteen minutes go by and it seems like all we've done is watch Ella and Frank and Dodger ride around and look at cattle and scenery. This is the part where it starts to become a proper neo-Western, you see. You couldn't just do a simple B-picture about a marauding land-grabber fighting a tough gunslinger in 1978. The greater meaning of Comes a Horseman grows out of the incredibly languor of its pacing: this is at heart a film about how much better things were back before all of this goddamn building and corruption and Me Decade crap got started. It's worth mentioning at this point, by the way, that Comes a Horseman isn't set so far in the past as we might assume. Almost without our noticing, things like cars and planes and neon signs start to appear here and there, and a good way into the film, reference is finally made to the impending end of "The War" - which, I assume, puts the film sometime in 1944, a very late date indeed for a Western, especially a Western adapted so clearly from the Shane model.

But I got ahead of myself. Comes a Horseman, in all its slow, gentle progression through virtually no plot at all, is at heart a mood piece; akin to (though much less effective than), its 1978 colleague Days of Heaven. We are meant to slow down and savor the very smooth, quiet patterns of the natural world and the cattle harvest; that is why so little happens, and that is why there are so many wide shots. Not that Pakula is any stranger to the wide shot, mind you - the wide shot might very well be the most characteristic visual quirk in his repertoire. It's customarily used in his films to indicate that we should be paying attention to the surroundings, the area in which the story takes place; because for Pakula, the way that story is shaped by setting is generally more interesting than the story itself. Comes a Horseman is no exception to that trend, except now the setting is the whole damn West, captured wonderfully in Panavision.

And, too, it is about the people who make their home in that place: Ella and Frank and Dodger especially, although J.W. starts off as a pretty interesting villain. As is typical for Pakula's work, it's the leading woman who is the most striking and interesting; I said in regards to Klute that it was easily the best moment of her whole career, and while Comes a Horseman absolutely does not call that into question, it does suggest that Pakula had a certain weird ability to draw her very best work out, because I think there's at least a possibility that this is her second-best moment. There is a deeply peaceful naturalism to her performance here that I don't think I've ever seen her attempt elsewhere, let alone match; her interpretation of Ella rises from the dirt of the landscape and simply resides there, not demanding much except with her soulful eyes (whether she'd ever been this good, I am quite certain that I've never seen Fonda this beautiful). She leaves poor James Caan far in the distance with a fine character given a fine performance, but nothing that leaps off the screen. Indeed, Caan might well be the least alive character in the movie: Farnsworth got a nomination for his peppy, deeply mournful performance as Dodger, and Robards plays his part with a gentleness that makes him seem much different - much richer - then the common or garden variety bad guy.

Nothing about this soft, simple character 'n landscape study is especially groundbreaking; even Willis's camerawork is uncharacteristically subtle, except for some interiors where he makes up for it with some of the most aggressive, even avant-garde dark-lit scenes he could muster up. It is however very appealing, and despite some mustiness in the scenario, fairly mature. It does one well to recall that for every boundary-piercing New Wave-influenced genre film in the 1970s, there were two very simple character studies about adults for adults, and though these had every bit as foul a lineage as their more kinetic brethren (from this line comes the horribly dull Ordinary People and all its kin), when they are done well, they are just plain effective, no analytical tricks required. Comes a Horseman is not exceptionally great; but it is certainly just plain effective.

Then, boom! the ending comes. I won't say what happens exactly, but I'll give you a good head start. After shame and embarrassment have come to J.W. he is, for the first time in the movie, a wholly pitiable man. We feel sorry for his losses. And then, just then, he steps from the colorfully realistic bad guy that he was all movie to a conniving Victorian cad, behaving like a black hat from a Gene Autry serial. Sadly, the protagonists follow suit: Frank instantly becomes a bloodless perfect marksman and fighter, and Ella becomes the roughest, crudest woman who ever fought against a land grab. Okay, that last part is constant throughout the film. But still, this quiet little character drama just up and becomes an action epic about burning houses down and blackmail, and all sorts of ugly things. You might just as well say it's from a different movie, and a much noisier and less satisfying one. I don't know what possessed Lynton Clark to write this ending, or Pakula to shoot it, but it changes the film dramatically, for the worse: suddenly this simple return to the very elemental character-based drama of Pakula's first films becomes an explosive, monstrous Thing. This is by far the biggest miscalculation of the director's career to this point, turning what might otherwise have been one of the numerous great lost gems of the 1970s into a good-enough Western that I can only really recommend to genre fans, or people who have some particularly strong affection for one or another of the actors.

We'll learn a lot more about the setting as the film goes on, but here's where things start: Ella Connors (Jane Fonda) has just buried her father and assumed control of his fading cattle ranch, and she is almost immediately assailed by her former flame, J.W. Ewing (Jason Robards), who is a greedy cattleman typical of these kinds of films. Ella and her trusty ranch hand Dodger (Richard Farnsworth) will have none of it, and it seems that J.W. has another enemy in the area, a certain Frank Athearn (James Caan). It makes sense for Frank and Ella to team up, at least initially; and then it makes sense for them to team up some more, and eventually they start to fall in love a little bit, although it takes more than an hour of movie and about one year of ranching for them to figure out that last part.

It is often said that this first screenplay by Dennis Lynton Clark - perhaps you know his production design work in A Man Called Horse? - is largely responsible for Comes a Horseman being a crashing bore, because he filled it up with one soggy stereotype after another and then made the whole thing take about three times as long as it had to. The conventional wisdom has a point: the screenplay is none too imaginative, and very little happens. But to jump straightaway to "the film is a bore" is a bit of a leap. For a start, this is a film in which Gordon Willis gets to set hisself to the task of capturing the wide open grandeur of the Colorado Rockies (standing in for Arizona), using all the tricks of his trade. There might well be a world in which "Gordon Willis shoots a Western" is boring. I do not reside in that world.

Setting that aside as just one man's raving cinematographer crush, the story in Comes a Horseman isn't exactly the life-sucking blight that some might call it. Yes, it is a slow piece; ten and fifteen minutes go by and it seems like all we've done is watch Ella and Frank and Dodger ride around and look at cattle and scenery. This is the part where it starts to become a proper neo-Western, you see. You couldn't just do a simple B-picture about a marauding land-grabber fighting a tough gunslinger in 1978. The greater meaning of Comes a Horseman grows out of the incredibly languor of its pacing: this is at heart a film about how much better things were back before all of this goddamn building and corruption and Me Decade crap got started. It's worth mentioning at this point, by the way, that Comes a Horseman isn't set so far in the past as we might assume. Almost without our noticing, things like cars and planes and neon signs start to appear here and there, and a good way into the film, reference is finally made to the impending end of "The War" - which, I assume, puts the film sometime in 1944, a very late date indeed for a Western, especially a Western adapted so clearly from the Shane model.

But I got ahead of myself. Comes a Horseman, in all its slow, gentle progression through virtually no plot at all, is at heart a mood piece; akin to (though much less effective than), its 1978 colleague Days of Heaven. We are meant to slow down and savor the very smooth, quiet patterns of the natural world and the cattle harvest; that is why so little happens, and that is why there are so many wide shots. Not that Pakula is any stranger to the wide shot, mind you - the wide shot might very well be the most characteristic visual quirk in his repertoire. It's customarily used in his films to indicate that we should be paying attention to the surroundings, the area in which the story takes place; because for Pakula, the way that story is shaped by setting is generally more interesting than the story itself. Comes a Horseman is no exception to that trend, except now the setting is the whole damn West, captured wonderfully in Panavision.

And, too, it is about the people who make their home in that place: Ella and Frank and Dodger especially, although J.W. starts off as a pretty interesting villain. As is typical for Pakula's work, it's the leading woman who is the most striking and interesting; I said in regards to Klute that it was easily the best moment of her whole career, and while Comes a Horseman absolutely does not call that into question, it does suggest that Pakula had a certain weird ability to draw her very best work out, because I think there's at least a possibility that this is her second-best moment. There is a deeply peaceful naturalism to her performance here that I don't think I've ever seen her attempt elsewhere, let alone match; her interpretation of Ella rises from the dirt of the landscape and simply resides there, not demanding much except with her soulful eyes (whether she'd ever been this good, I am quite certain that I've never seen Fonda this beautiful). She leaves poor James Caan far in the distance with a fine character given a fine performance, but nothing that leaps off the screen. Indeed, Caan might well be the least alive character in the movie: Farnsworth got a nomination for his peppy, deeply mournful performance as Dodger, and Robards plays his part with a gentleness that makes him seem much different - much richer - then the common or garden variety bad guy.

Nothing about this soft, simple character 'n landscape study is especially groundbreaking; even Willis's camerawork is uncharacteristically subtle, except for some interiors where he makes up for it with some of the most aggressive, even avant-garde dark-lit scenes he could muster up. It is however very appealing, and despite some mustiness in the scenario, fairly mature. It does one well to recall that for every boundary-piercing New Wave-influenced genre film in the 1970s, there were two very simple character studies about adults for adults, and though these had every bit as foul a lineage as their more kinetic brethren (from this line comes the horribly dull Ordinary People and all its kin), when they are done well, they are just plain effective, no analytical tricks required. Comes a Horseman is not exceptionally great; but it is certainly just plain effective.

Then, boom! the ending comes. I won't say what happens exactly, but I'll give you a good head start. After shame and embarrassment have come to J.W. he is, for the first time in the movie, a wholly pitiable man. We feel sorry for his losses. And then, just then, he steps from the colorfully realistic bad guy that he was all movie to a conniving Victorian cad, behaving like a black hat from a Gene Autry serial. Sadly, the protagonists follow suit: Frank instantly becomes a bloodless perfect marksman and fighter, and Ella becomes the roughest, crudest woman who ever fought against a land grab. Okay, that last part is constant throughout the film. But still, this quiet little character drama just up and becomes an action epic about burning houses down and blackmail, and all sorts of ugly things. You might just as well say it's from a different movie, and a much noisier and less satisfying one. I don't know what possessed Lynton Clark to write this ending, or Pakula to shoot it, but it changes the film dramatically, for the worse: suddenly this simple return to the very elemental character-based drama of Pakula's first films becomes an explosive, monstrous Thing. This is by far the biggest miscalculation of the director's career to this point, turning what might otherwise have been one of the numerous great lost gems of the 1970s into a good-enough Western that I can only really recommend to genre fans, or people who have some particularly strong affection for one or another of the actors.

Categories: alan j pakula, new hollywood cinema, westerns