Object permanence

I do not know what the Frenchest of all film genres is, but if I were invited to submit a shortlist, one of the candidates would surely be the ever-popular drama about a family that quietly tears itself apart through unspoken resentments and bitterness. In fact, the mere fact that I can casually refer to that as a genre is pretty damn French all by itself.

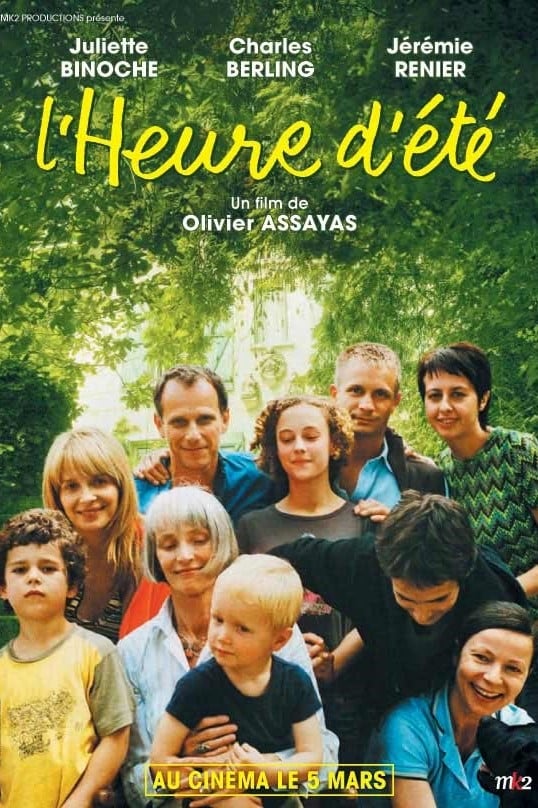

One of modern France's most prominent directors, Olivier Assayas, hasn't really made a film in this supremely French mode before; nor has he worked with the quintessentially French actress Juliette Binoche before; and happily, he's killed both of those birds with one stone in Summer Hours, and the result is pretty much the most incredibly French movie that you'll see in America all year. Which I hold to be a compliment, but your mileage may vary, you horrid xenophobic Yankee.

Like many European dramas, Summer Hours doesn't look like it has any plot at all: Hélène (Edith Scob), the niece of an important painter who has taken over his country home and extensive collection of Art Nouveau furniture, passes away a few months after her 75th birthday, leaving her three children - Frédéric (Charles Berling), a Paris-based economist, Adrienne (Juliette Binoche), a designer of home accessories living in New York, and Jérémie (Jérémie Renier), an executive with Puma who lives in China overseeing the production of shoes - to determine what to do with the sprawling old house full of countless rare and priceless antiques that they all have some emotional attachment towards, but not really any good use for.

Assayas has suggested that this is his Chekhov film, a hubristic thing to claim if every there was one, but it's not all that hard to see where he was driving at, from a narrative point of view (Summer Hours feels much like a 21st Century, globalised world version of The Cherry Orchard) and too from the film's eerie simplicity and harrowing emotional depth. Considering how much nothing makes up the story, Summer Hours is one hell of a meaningful work of cinema, a study of nothing less than the way that memories and past identity are built, saved, and destroyed. In doesn't take a Ph.D in metaphor deconstruction to understand that the three siblings are taking their childhood and all their history up to this point in middle age, putting it in a box, saying a very tender goodbye, and getting rid of it.

The film thus takes as its chief theme the way that personal history, memory, and nostalgia are triggered by particular objects and places, and the way in which those things can be negated or discarded by nothing more malicious than brute pragmatism.* There's no indication that the siblings are anxious to be done with their past and each other - and it's more than likely that the last time we see them together is indeed the last time they'll ever be together, unless its for each others' funerals - but with Adrienne in North America and Jérémie in Asia, it's really just too much to expect that things will keep on the way they've been. This isn't treated with judgment; indeed, the whole movie is largely content simply to present situations as being what they must be, and that's just life.

Despite having such an apparent lack of inflection, Assayas manages to bring deep, heartfelt emotion from the tiniest corners of his movie: in the way that Frédéric's children, Sylvie (Alice de Lencquesaing) and Pierre (Emile Berling, the son of the actor playing his father) feel a touch of guilt at being so indifferent to the loss of their family's heritage; in the way that Éloise (Isabelle Sadoyan), Hélène's housekeeper from time out of mind, considers all the chatter about the artistic value of the collection and the question of whether it belongs in a museum to be contemptible, seeing as it degrades the human value of the objects that have been part of her daily life for years upon years. Countless fussy little human moments fill every scene, giving the film a great richness that makes it all the more sorrowful for the audience, making these fictional characters as real as any flesh and blood human.

That's enough right there for the film to qualify as a great work, but there's more to it. Assayas being who he is, the film treats significantly but subtly on the nature of global culture, and what it means to identify with the place of one's birth in a world where the shoes a Frenchman sells in America are made in China; the question of whether it is a good thing that young people, in forming generational identity, readily ignore the culture of their parents is addressed but not answered, seeing as no definitive answer is possible; and the relative value of placing cultural objects in museums is discussed, with answers that might not entirely please the Musée d'Orsay, which commissioned this film (as well as Hou Hsiao-Hsien's Flight of the Red Balloon) in celebration of its 20th anniversary: in the film's extraordinary second to last scene, visiting Hélène's collection in the museum where it was eventually sent - not coincidentally, the Musée d'Orsay - Frédéric's wife Lisa (Dominique Reymond) suggests that by giving the pieces to the world, the family has saved them and given them a kind of immortality. True enough, counters Frédéric, but in so doing they have robbed them of life; the gorgeous, rare vases locked in a glass case were never lovelier than in the afternoon sun, full of new-cut flowers. And damned if Frédéric doesn't have a good point.

On the other hand, the film's very last scene suggests something else, not a denial of that melancholy, exactly, but a belief that there's more to it than just seeing one's past shut up under glass. Sylvie and Pierre throw a raging party full of horny teens in the old house, a short while before its title is transferred, and thus do we see not that the kids have denied their family's past: they have redefined it for themselves, and come into a kind of transcendence. The film's last image is a tracking shot that quite unexpectedly turns into a crane shot at just the right time for it to break your heart and bring a tear to your eye, and if you don't know how a crane shot can do those things, well, go see Summer Hours.

Now that I've gone and made the film sound like the dourest experience under the sun, let me backtrack, and say that this is as delicate, even effervescent, as any story about the dissolution of family ties could possibly be. Assayas is working in a strikingly different mode than I at least have ever seen: where his most famous films in the States are an angry satire of French film history (Irma Vep) and a genre-bending thriller about sex and the information age global economy (demonlover) Summer Hours is as diaphanous as a soap bubble. It boasts spare cinematography by Eric Gautier (a genius perpetually under-appreciated in America) that presents a lovely palette of gentle colors and soft shadows, and never forces anything upon the viewer; it contains a subdued soundtrack in which nothing loud and startling is ever heard; it is an easy and relaxing film that is so quiet in its movements that even though it demands far more intellectual engagement and patience that most American films, even the ones made for adults, would dare to ask for, it possesses such a light touch that it hardly seems to make any demands at all. This is the quintessence of art.

One of modern France's most prominent directors, Olivier Assayas, hasn't really made a film in this supremely French mode before; nor has he worked with the quintessentially French actress Juliette Binoche before; and happily, he's killed both of those birds with one stone in Summer Hours, and the result is pretty much the most incredibly French movie that you'll see in America all year. Which I hold to be a compliment, but your mileage may vary, you horrid xenophobic Yankee.

Like many European dramas, Summer Hours doesn't look like it has any plot at all: Hélène (Edith Scob), the niece of an important painter who has taken over his country home and extensive collection of Art Nouveau furniture, passes away a few months after her 75th birthday, leaving her three children - Frédéric (Charles Berling), a Paris-based economist, Adrienne (Juliette Binoche), a designer of home accessories living in New York, and Jérémie (Jérémie Renier), an executive with Puma who lives in China overseeing the production of shoes - to determine what to do with the sprawling old house full of countless rare and priceless antiques that they all have some emotional attachment towards, but not really any good use for.

Assayas has suggested that this is his Chekhov film, a hubristic thing to claim if every there was one, but it's not all that hard to see where he was driving at, from a narrative point of view (Summer Hours feels much like a 21st Century, globalised world version of The Cherry Orchard) and too from the film's eerie simplicity and harrowing emotional depth. Considering how much nothing makes up the story, Summer Hours is one hell of a meaningful work of cinema, a study of nothing less than the way that memories and past identity are built, saved, and destroyed. In doesn't take a Ph.D in metaphor deconstruction to understand that the three siblings are taking their childhood and all their history up to this point in middle age, putting it in a box, saying a very tender goodbye, and getting rid of it.

The film thus takes as its chief theme the way that personal history, memory, and nostalgia are triggered by particular objects and places, and the way in which those things can be negated or discarded by nothing more malicious than brute pragmatism.* There's no indication that the siblings are anxious to be done with their past and each other - and it's more than likely that the last time we see them together is indeed the last time they'll ever be together, unless its for each others' funerals - but with Adrienne in North America and Jérémie in Asia, it's really just too much to expect that things will keep on the way they've been. This isn't treated with judgment; indeed, the whole movie is largely content simply to present situations as being what they must be, and that's just life.

Despite having such an apparent lack of inflection, Assayas manages to bring deep, heartfelt emotion from the tiniest corners of his movie: in the way that Frédéric's children, Sylvie (Alice de Lencquesaing) and Pierre (Emile Berling, the son of the actor playing his father) feel a touch of guilt at being so indifferent to the loss of their family's heritage; in the way that Éloise (Isabelle Sadoyan), Hélène's housekeeper from time out of mind, considers all the chatter about the artistic value of the collection and the question of whether it belongs in a museum to be contemptible, seeing as it degrades the human value of the objects that have been part of her daily life for years upon years. Countless fussy little human moments fill every scene, giving the film a great richness that makes it all the more sorrowful for the audience, making these fictional characters as real as any flesh and blood human.

That's enough right there for the film to qualify as a great work, but there's more to it. Assayas being who he is, the film treats significantly but subtly on the nature of global culture, and what it means to identify with the place of one's birth in a world where the shoes a Frenchman sells in America are made in China; the question of whether it is a good thing that young people, in forming generational identity, readily ignore the culture of their parents is addressed but not answered, seeing as no definitive answer is possible; and the relative value of placing cultural objects in museums is discussed, with answers that might not entirely please the Musée d'Orsay, which commissioned this film (as well as Hou Hsiao-Hsien's Flight of the Red Balloon) in celebration of its 20th anniversary: in the film's extraordinary second to last scene, visiting Hélène's collection in the museum where it was eventually sent - not coincidentally, the Musée d'Orsay - Frédéric's wife Lisa (Dominique Reymond) suggests that by giving the pieces to the world, the family has saved them and given them a kind of immortality. True enough, counters Frédéric, but in so doing they have robbed them of life; the gorgeous, rare vases locked in a glass case were never lovelier than in the afternoon sun, full of new-cut flowers. And damned if Frédéric doesn't have a good point.

On the other hand, the film's very last scene suggests something else, not a denial of that melancholy, exactly, but a belief that there's more to it than just seeing one's past shut up under glass. Sylvie and Pierre throw a raging party full of horny teens in the old house, a short while before its title is transferred, and thus do we see not that the kids have denied their family's past: they have redefined it for themselves, and come into a kind of transcendence. The film's last image is a tracking shot that quite unexpectedly turns into a crane shot at just the right time for it to break your heart and bring a tear to your eye, and if you don't know how a crane shot can do those things, well, go see Summer Hours.

Now that I've gone and made the film sound like the dourest experience under the sun, let me backtrack, and say that this is as delicate, even effervescent, as any story about the dissolution of family ties could possibly be. Assayas is working in a strikingly different mode than I at least have ever seen: where his most famous films in the States are an angry satire of French film history (Irma Vep) and a genre-bending thriller about sex and the information age global economy (demonlover) Summer Hours is as diaphanous as a soap bubble. It boasts spare cinematography by Eric Gautier (a genius perpetually under-appreciated in America) that presents a lovely palette of gentle colors and soft shadows, and never forces anything upon the viewer; it contains a subdued soundtrack in which nothing loud and startling is ever heard; it is an easy and relaxing film that is so quiet in its movements that even though it demands far more intellectual engagement and patience that most American films, even the ones made for adults, would dare to ask for, it possesses such a light touch that it hardly seems to make any demands at all. This is the quintessence of art.