Mann's Men

In the spring of 1979, a 36-year-old nobody got a chance to make a TV movie. I take that back, not a nobody: he'd written a few episodes of some different cop shows, and directed an episode of the Angie Dickinson series Police Woman, and lest we forget, back in the '70s there was no mid-budget indie cinema to use as a talent farm for new filmmakers. Graduation from essentially anonymous series work to a feature-length television project wasn't all that uncommon, in those days when telefilms were themselves not all that uncommon. Many people did that same thing; many fewer were able to use that as the jumping-off point for a major career.

The end of that little anecdote, I'm sure you've guessed, is that the 36-year-old had quite a success indeed; after co-writing and directing The Jericho Mile, Michael Mann was quickly transformed into one of the hottest new faces in Hollywood. And it the story of what he did with all that hotness that we are here to recall this June.

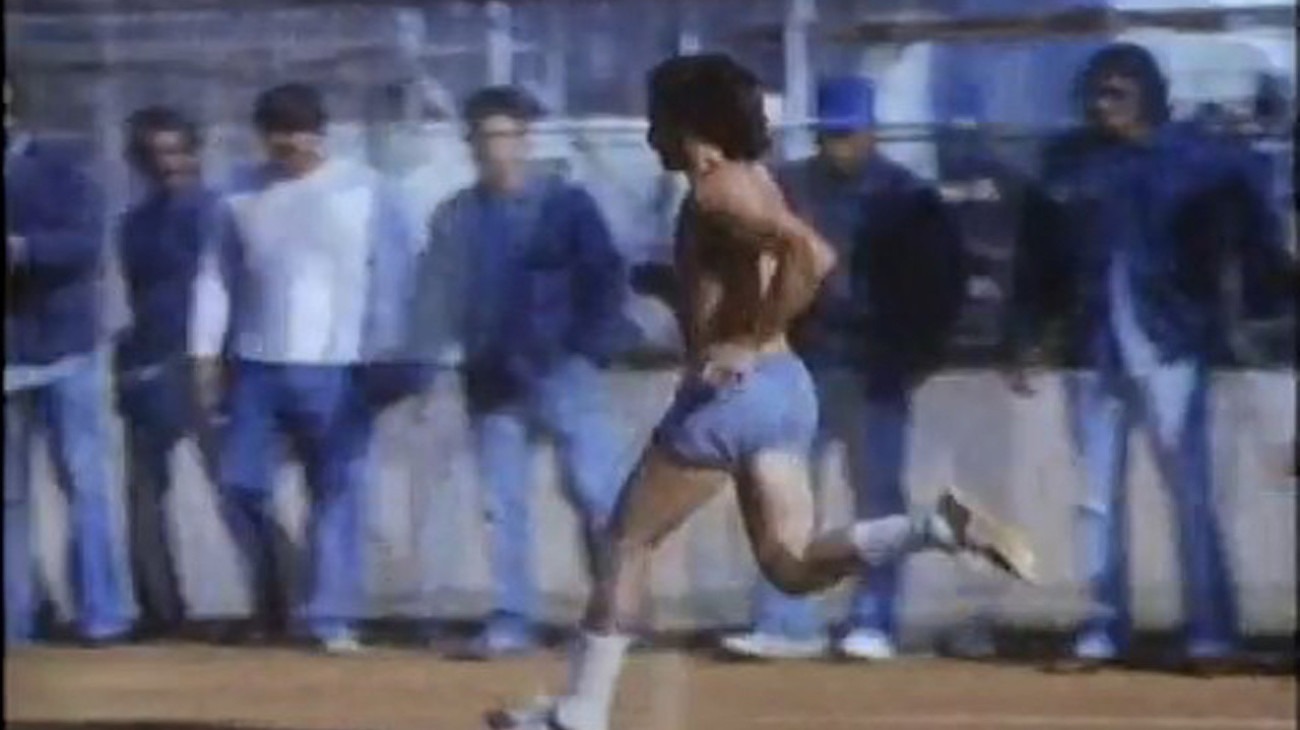

So, The Jericho Mile: with a title like that, you could probably guess at last that it has something to do with running; I'd be terribly surprised if you guessed that it was set in a prison. But it is, and those two things pretty much describe the entirety of the movie's generic concerns: a movie about an imprisoned runner. Specifically, it's about a fellow named "Rain" Murphy, played by TV-movie veteran Peter Strauss (who won an Emmy for his work here; the film itself did not, losing to the Vietnam-themed Friendly Fire, while Mann wasn't even nominated for directing, though he won for writing). Murphy is serving a life sentence in California's Folsom State Prison for murder, and to keep himself sane for the next few decades, he runs in the prison yard during the inmates' free time. And that's all he does: he doesn't commit himself to the prison's rehabilitation programs, he doesn't learn any practical skills, and he hardly speaks to any of the other inmates, save for R.C. Stiles (Richard Lawson), the African-American prisoner in the next cell over who is the closest thing Murphy has to a friend in Folsom.

Thing is, Murphy doesn't just run, he runs really well, enough to grab the attention of warden Earl Gulliver (Billy Green Bush), who starts to wonder if there may be something worth exploiting in this young man who has self-taught himself to run a four-minute mile; it's hard to say whether Gulliver is motivated by the hope that Folsom producing a world-class athlete will be a gold star on his own record, if he genuinely has some desire for Murphy's success, or if its something else, but he puts a lot of effort into convincing the people who officially record such things to take a look at Murphy for - maybe? - serving on the U.S. Olympic team in 1980. Murphy will have none of it, though: prison is a bad enough place, with the vicious druglord Dr. D (Brian Dennehy) who takes out violent revenge on Stiles for refusing to be a cocaine mule. There's more to it than just wanting to remain safe and anonymous in the deadly land of Folsom, though: the more we get to know Murphy, the more we realise that he is quite invested in the idea that his crime is so infamous that he ought to rot away in prison, and becoming a sports star would perhaps get in the way of his atonement.

Someone I know who is much more familiar with Mann's career than I am has suggested that the overarching them of all the director's movies is this: a man who lives by a code of honor and morality is presented with a situation which puts that code into crisis. This is a perfectly handy way to think about the central dramatic situation in The Jericho Mile, which is essentially that Murphy believes, honestly and truly, that the correct thing is for his personality to be devoured by his self-imposed isolation from even the debased society present in Folsom. When we finally learn the truth of Murphy's crime, it makes him a great deal more sympathetic to us - he protected his sister from the rapacious advances of their father by killing the older man - yet to Murphy, there is no forgiving his sin. He killed the man that raised him and who figures at the center of his fondest memories of childhood. His penitence is to run, for in running he loses any sense of himself or his entrapment; the only thing he knows is the feeling of pushing his body to its limits.

With that sublimely meaty role to play, Strauss gives one of the great one-off performances in television history; great enough that it makes you want to stamp your feet and pound your fists and shout, "how is it that I have never heard of this brilliant actor?" He anchors the movie with a commanding presence, and he indicates with delicate subtlety how Murphy feels at any moment, and let us see with great deliberate slowness how the character learns to have a sense of his own worth as a result of his athletic achievement, culminating in a discussion with one of the officials looking to see if he's a good enough human being to represent his country in the Olympiad. We know he is, and Murphy only in this instant realises that he is - and in this instant realises too that he is good enough not to have to submit to the bigotry and petty needling he sees before him. It's the movie's finest scene, largely because of Strauss.

Mann makes the best choice a director can make with a performance like this: he stays the hell out of the way. This is both a good thing and a bad thing; good, because Strauss is good enough to carry a lot of the film on his shoulders, and bad because the rest of the movie isn't nearly up to the same level. Not that Mann does a shoddy job directing, mind: after Strauss, he's easily the most important person involved with the film's creation. Not for one frame does The Jericho Mile look like a project made for television, and I think this accounts for one part of the reason that Mann became such a desirable commodity immediately after the film's premiere: he'd effectively proven that he could make a theatrical movie without ever having to actually make one. The other part is Folsom itself: the movie was shot on location and could not have had a portion of the same effectiveness if that weren't the case. Folsom is a character, the combination of all the characters living inside its walls, and Mann's skill at capturing the physical sense of that place, with all its danger and filth, marked him quickly as a great location director, something he'd prove several times again in the ensuing years.

Yet, for a man who has come to be known as a great stylist, there's not much visually interesting in The Jericho Mile; and there's absolutely nothing worthwhile in all the other characters and subplots peppering the prison. Stiles is a wince-inducing stereotype; the kind that white liberals might have thought was progressive in the late-'70s, but it's hard to watch him now without feeling a bit uncomfortable. And he's by far the richest character in the movie after Murphy. Simply put, The Jericho Mile falls into the common trap of putting all of its egg in one basket, Strauss - two if we count the location - and hoping that the quality of that basket will support the rest of the film, with its paint-by-numbers screenplay and people. Largely, Mann's gamble pays off in this case; but when all is said and done, The Jericho Mile, though by and large a success, is somewhat more disposable than you might think at first blush. It's a very fine prison drama, but it never attempts to reach true greatness.

The end of that little anecdote, I'm sure you've guessed, is that the 36-year-old had quite a success indeed; after co-writing and directing The Jericho Mile, Michael Mann was quickly transformed into one of the hottest new faces in Hollywood. And it the story of what he did with all that hotness that we are here to recall this June.

So, The Jericho Mile: with a title like that, you could probably guess at last that it has something to do with running; I'd be terribly surprised if you guessed that it was set in a prison. But it is, and those two things pretty much describe the entirety of the movie's generic concerns: a movie about an imprisoned runner. Specifically, it's about a fellow named "Rain" Murphy, played by TV-movie veteran Peter Strauss (who won an Emmy for his work here; the film itself did not, losing to the Vietnam-themed Friendly Fire, while Mann wasn't even nominated for directing, though he won for writing). Murphy is serving a life sentence in California's Folsom State Prison for murder, and to keep himself sane for the next few decades, he runs in the prison yard during the inmates' free time. And that's all he does: he doesn't commit himself to the prison's rehabilitation programs, he doesn't learn any practical skills, and he hardly speaks to any of the other inmates, save for R.C. Stiles (Richard Lawson), the African-American prisoner in the next cell over who is the closest thing Murphy has to a friend in Folsom.

Thing is, Murphy doesn't just run, he runs really well, enough to grab the attention of warden Earl Gulliver (Billy Green Bush), who starts to wonder if there may be something worth exploiting in this young man who has self-taught himself to run a four-minute mile; it's hard to say whether Gulliver is motivated by the hope that Folsom producing a world-class athlete will be a gold star on his own record, if he genuinely has some desire for Murphy's success, or if its something else, but he puts a lot of effort into convincing the people who officially record such things to take a look at Murphy for - maybe? - serving on the U.S. Olympic team in 1980. Murphy will have none of it, though: prison is a bad enough place, with the vicious druglord Dr. D (Brian Dennehy) who takes out violent revenge on Stiles for refusing to be a cocaine mule. There's more to it than just wanting to remain safe and anonymous in the deadly land of Folsom, though: the more we get to know Murphy, the more we realise that he is quite invested in the idea that his crime is so infamous that he ought to rot away in prison, and becoming a sports star would perhaps get in the way of his atonement.

Someone I know who is much more familiar with Mann's career than I am has suggested that the overarching them of all the director's movies is this: a man who lives by a code of honor and morality is presented with a situation which puts that code into crisis. This is a perfectly handy way to think about the central dramatic situation in The Jericho Mile, which is essentially that Murphy believes, honestly and truly, that the correct thing is for his personality to be devoured by his self-imposed isolation from even the debased society present in Folsom. When we finally learn the truth of Murphy's crime, it makes him a great deal more sympathetic to us - he protected his sister from the rapacious advances of their father by killing the older man - yet to Murphy, there is no forgiving his sin. He killed the man that raised him and who figures at the center of his fondest memories of childhood. His penitence is to run, for in running he loses any sense of himself or his entrapment; the only thing he knows is the feeling of pushing his body to its limits.

With that sublimely meaty role to play, Strauss gives one of the great one-off performances in television history; great enough that it makes you want to stamp your feet and pound your fists and shout, "how is it that I have never heard of this brilliant actor?" He anchors the movie with a commanding presence, and he indicates with delicate subtlety how Murphy feels at any moment, and let us see with great deliberate slowness how the character learns to have a sense of his own worth as a result of his athletic achievement, culminating in a discussion with one of the officials looking to see if he's a good enough human being to represent his country in the Olympiad. We know he is, and Murphy only in this instant realises that he is - and in this instant realises too that he is good enough not to have to submit to the bigotry and petty needling he sees before him. It's the movie's finest scene, largely because of Strauss.

Mann makes the best choice a director can make with a performance like this: he stays the hell out of the way. This is both a good thing and a bad thing; good, because Strauss is good enough to carry a lot of the film on his shoulders, and bad because the rest of the movie isn't nearly up to the same level. Not that Mann does a shoddy job directing, mind: after Strauss, he's easily the most important person involved with the film's creation. Not for one frame does The Jericho Mile look like a project made for television, and I think this accounts for one part of the reason that Mann became such a desirable commodity immediately after the film's premiere: he'd effectively proven that he could make a theatrical movie without ever having to actually make one. The other part is Folsom itself: the movie was shot on location and could not have had a portion of the same effectiveness if that weren't the case. Folsom is a character, the combination of all the characters living inside its walls, and Mann's skill at capturing the physical sense of that place, with all its danger and filth, marked him quickly as a great location director, something he'd prove several times again in the ensuing years.

Yet, for a man who has come to be known as a great stylist, there's not much visually interesting in The Jericho Mile; and there's absolutely nothing worthwhile in all the other characters and subplots peppering the prison. Stiles is a wince-inducing stereotype; the kind that white liberals might have thought was progressive in the late-'70s, but it's hard to watch him now without feeling a bit uncomfortable. And he's by far the richest character in the movie after Murphy. Simply put, The Jericho Mile falls into the common trap of putting all of its egg in one basket, Strauss - two if we count the location - and hoping that the quality of that basket will support the rest of the film, with its paint-by-numbers screenplay and people. Largely, Mann's gamble pays off in this case; but when all is said and done, The Jericho Mile, though by and large a success, is somewhat more disposable than you might think at first blush. It's a very fine prison drama, but it never attempts to reach true greatness.

Categories: michael mann, new hollywood cinema, sports films