To be and not to be

Ramin Bahrani is a 35-year-old North Carolina native of Iranian descent, a writer-director-editor of three films that are essentially unknown outside of the art house and festival set, and another feature that - as far as I can figure out - has never had any kind of real release anywhere in the world, and he is probably the most important independent filmmaker working in America right now.

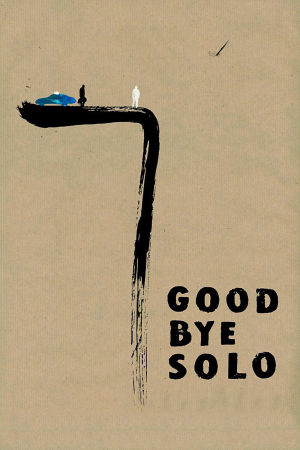

I say this upon viewing Goodbye Solo, his most recent film and winner of the FIPRESCI Prize at the 2008 Venice Film Festival. Like his previous work, it is about the experience of non-white immigrants on the fringe of urban society; like them, it speaks to a storytelling and filmmaking discipline that doesn't seem to exist anywhere else in the world.

The Solo of the title is a Senegalese cab driver in Winston-Salem, played by non-professional actor Souleymane Sy Savane, who prior to making the movie was himself a cab driver in Winston-Salem. He spends most of his time onscreen chauffeuring an old man named William (Red West, a friend of Elvis Presley's from high school), who offers him $1000 to drive him to Blowing Rock, a natural oddity in the Blu Ridge Mountains, leave him there, and drive back to the city without asking any questions. Solo assumes what most of us probably would, that William is planning to end his life by jumping off the 3000-foot cliff, and he elects to worm his way into William's life to find out what would drive him to suicide, and to attempt to become the old man's friend, thereby giving him a reason to live.

In the abstract, that sounds a bit like a reverse of Abbas Kiarostami's Taste of Cherry, and I'd imagine that I'm not alone in assuming that the younger filmmaker is at least generally familiar with the Iranian master's work. In the end, Goodbye Solo is nothing like Taste of Cherry at all, save that both films prove to be about other things entirely than what appears to be their central conflict. In the particular case of Bahrani's film, what starts out on the path to becoming a straightforward buddy dramedy about people who need people being the luckiest people - or even more ghastly, a story of a Magical Negro saving a lost white person from his fate - ends as a nigh-indescribable character study about choices made and plans abandoned, about the things we wished we'd done, about the tricks we play on ourselves to keep pushing through life when it becomes obvious that the world isn't terribly keen on making things at all easy for us.

What unforgivable drudgery I've just described! Yet that's not Goodbye Solo at all - it's a film that hums with life and with good humor, thanks to the presence of Solo, as fine a depiction of an unflagging optimist as you're going to see in a movie theater this year (if not for Mike Leigh and his damned Happy-Go-Lucky, I'd have been able to call Solo the finest cinematic optimist in recent memory). It diminishes the film considerably to reduce it to a simple schematic, where Solo = Life and William = Death, but that's at least a reasonable way to prod at the movie a little bit. To Solo, the very idea that one can be so tired of life as to seek out a way to end it is inconceivable; his own existence is hardly ideal and he knows it, but to suffer disappointments and hurts is simply a way of demonstrating that yes, we are here on this earth.

Bahrani could present this in a straightforward way, and it is true that Goodbye Solo is considerably easier than the director's reigning masterpiece Man Push Cart, simply by virtue of having a recognisable narrative through-line. But even if it's slightly more ordinary compared to its illustrious predecessor, there's nothing about the film that is easily lumped into familiar categories. Even the way the story, such as it is, moves forward speaks to an extraordinary way of thinking about storytelling: in the film's very first scene, Solo and William have already known each other for some time, the deal has been offered and accepted, Solo has already tried and attempted to dissuade William from his path (which is never explicitly identified at any point in the film), and William has already grown tired of this pushy cabbie trying to stick his nose where it doesn't belong. So the very dynamic that drives the whole movie isn't just extant at the earliest moment we see the characters; it's already growing stale. It's partially for this reason that the film isn't really about the Solo/William relationship in the sense you'd expect it to be, but about how the two men's response to that relationship shapes them separately in the last week they spend together.

Because the film is more about Solo and William rather than Solo&William (if you catch my meaning), it's even less about its own narrative than I think I'm making it seem: it's about place and culture and different ways of existing in the world, with the plot reduced to at best an obligation that has to be wrapped up (in the final scenes when the plot does take over, the film becomes a completely different visual experience than it had been to that point). Like he's done before, Bahrani is at his most engaged when he simply trains the camera on characters, played by actors who probably have been living these roles all their lives, acting as they will naturally, without letting the plot move them about. It nudges into documentary territory in strange ways that recall some of Werner Herzog's more aggressive experiments in blending fiction and reality in things like The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser and Heart of Glass, though in no other way do Bahrani and Herzog's aesthetics overlap.

About Bahrani's aesthetic: it's perfectly familiar to anyone who's seen Man Push Cart or Chop Shop, but not like anything else in current American cinema, or indeed much else besides a handful of specific filmmakers cherry-picked from history. He uses longish takes that aren't so long that their length is the point; he uses a free mixture of close-ups and medium shots that is sufficiently varied that it's not until later that you really notice the near-total absence of anything wider (I was shocked in one scene, late in the film, to realise that I hadn't seen William's legs prior to that moment). There are many points where the camera seems to adopt one characters exact point-of-view, watching something he can't hear; there are a few points where we can hear something that we're not looking at. None of it's terribly familiar, but it's not really artsy or avant-garde in effect.

The effect is rather to stress the characters, setting us next to them and almost inside them in certain ways, and tying us down to how their environment fits around them, rather than how they fit in to their environment. Above all things else, Goodbye Solo is a uniquely human-sized movie, and the humans in it are impeccable creations both on the part of their writers and the supremely gifted amateurs playing them. This is why, no matter how grim the matter of the film may be (poverty, suicide, failure, abandonment), it never really feels depressing or more than intermittently sad. It is about human beings living, and what a miraculous and special thing that is. This is a tremendously special film, and the man who made it is a godsend to the art of cinema.

9/10

I say this upon viewing Goodbye Solo, his most recent film and winner of the FIPRESCI Prize at the 2008 Venice Film Festival. Like his previous work, it is about the experience of non-white immigrants on the fringe of urban society; like them, it speaks to a storytelling and filmmaking discipline that doesn't seem to exist anywhere else in the world.

The Solo of the title is a Senegalese cab driver in Winston-Salem, played by non-professional actor Souleymane Sy Savane, who prior to making the movie was himself a cab driver in Winston-Salem. He spends most of his time onscreen chauffeuring an old man named William (Red West, a friend of Elvis Presley's from high school), who offers him $1000 to drive him to Blowing Rock, a natural oddity in the Blu Ridge Mountains, leave him there, and drive back to the city without asking any questions. Solo assumes what most of us probably would, that William is planning to end his life by jumping off the 3000-foot cliff, and he elects to worm his way into William's life to find out what would drive him to suicide, and to attempt to become the old man's friend, thereby giving him a reason to live.

In the abstract, that sounds a bit like a reverse of Abbas Kiarostami's Taste of Cherry, and I'd imagine that I'm not alone in assuming that the younger filmmaker is at least generally familiar with the Iranian master's work. In the end, Goodbye Solo is nothing like Taste of Cherry at all, save that both films prove to be about other things entirely than what appears to be their central conflict. In the particular case of Bahrani's film, what starts out on the path to becoming a straightforward buddy dramedy about people who need people being the luckiest people - or even more ghastly, a story of a Magical Negro saving a lost white person from his fate - ends as a nigh-indescribable character study about choices made and plans abandoned, about the things we wished we'd done, about the tricks we play on ourselves to keep pushing through life when it becomes obvious that the world isn't terribly keen on making things at all easy for us.

What unforgivable drudgery I've just described! Yet that's not Goodbye Solo at all - it's a film that hums with life and with good humor, thanks to the presence of Solo, as fine a depiction of an unflagging optimist as you're going to see in a movie theater this year (if not for Mike Leigh and his damned Happy-Go-Lucky, I'd have been able to call Solo the finest cinematic optimist in recent memory). It diminishes the film considerably to reduce it to a simple schematic, where Solo = Life and William = Death, but that's at least a reasonable way to prod at the movie a little bit. To Solo, the very idea that one can be so tired of life as to seek out a way to end it is inconceivable; his own existence is hardly ideal and he knows it, but to suffer disappointments and hurts is simply a way of demonstrating that yes, we are here on this earth.

Bahrani could present this in a straightforward way, and it is true that Goodbye Solo is considerably easier than the director's reigning masterpiece Man Push Cart, simply by virtue of having a recognisable narrative through-line. But even if it's slightly more ordinary compared to its illustrious predecessor, there's nothing about the film that is easily lumped into familiar categories. Even the way the story, such as it is, moves forward speaks to an extraordinary way of thinking about storytelling: in the film's very first scene, Solo and William have already known each other for some time, the deal has been offered and accepted, Solo has already tried and attempted to dissuade William from his path (which is never explicitly identified at any point in the film), and William has already grown tired of this pushy cabbie trying to stick his nose where it doesn't belong. So the very dynamic that drives the whole movie isn't just extant at the earliest moment we see the characters; it's already growing stale. It's partially for this reason that the film isn't really about the Solo/William relationship in the sense you'd expect it to be, but about how the two men's response to that relationship shapes them separately in the last week they spend together.

Because the film is more about Solo and William rather than Solo&William (if you catch my meaning), it's even less about its own narrative than I think I'm making it seem: it's about place and culture and different ways of existing in the world, with the plot reduced to at best an obligation that has to be wrapped up (in the final scenes when the plot does take over, the film becomes a completely different visual experience than it had been to that point). Like he's done before, Bahrani is at his most engaged when he simply trains the camera on characters, played by actors who probably have been living these roles all their lives, acting as they will naturally, without letting the plot move them about. It nudges into documentary territory in strange ways that recall some of Werner Herzog's more aggressive experiments in blending fiction and reality in things like The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser and Heart of Glass, though in no other way do Bahrani and Herzog's aesthetics overlap.

About Bahrani's aesthetic: it's perfectly familiar to anyone who's seen Man Push Cart or Chop Shop, but not like anything else in current American cinema, or indeed much else besides a handful of specific filmmakers cherry-picked from history. He uses longish takes that aren't so long that their length is the point; he uses a free mixture of close-ups and medium shots that is sufficiently varied that it's not until later that you really notice the near-total absence of anything wider (I was shocked in one scene, late in the film, to realise that I hadn't seen William's legs prior to that moment). There are many points where the camera seems to adopt one characters exact point-of-view, watching something he can't hear; there are a few points where we can hear something that we're not looking at. None of it's terribly familiar, but it's not really artsy or avant-garde in effect.

The effect is rather to stress the characters, setting us next to them and almost inside them in certain ways, and tying us down to how their environment fits around them, rather than how they fit in to their environment. Above all things else, Goodbye Solo is a uniquely human-sized movie, and the humans in it are impeccable creations both on the part of their writers and the supremely gifted amateurs playing them. This is why, no matter how grim the matter of the film may be (poverty, suicide, failure, abandonment), it never really feels depressing or more than intermittently sad. It is about human beings living, and what a miraculous and special thing that is. This is a tremendously special film, and the man who made it is a godsend to the art of cinema.

9/10