The Gospel truth

And now, the notorious Pier Paolo Pasolini makes his first appearance in this blog! The Italian filmmaker of the 1960s and '70s known best for his unabashed Marxism and his late run of movies so outrageous as to border on the grotesque and pornographic, culminating in the infamous Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, a work with the shadowy reputation of being so overstuffed with sociological pretension that even the most pretentious audience finds it hard going, and so appalling in its violence and scatology that only the most blood-hungry gorehounds can make it through without blanching.

Today, we meet the director long before those days of his most terrible reputation, in 1964. In the earlier parts of his career, Pasolini was naught but a Neo-Realist, continuing the post-war tradition of Vittorio De Sica and Roberto Rossellini in making pseudo-documentary films about the crushing condition of impoverished life in Italy. Even in these first films, Pasolini could never be mistaken for anything but a controversialist; while the filmmakers of the generation before him were regarded in their own day as the next things to Communists, the modern reputation of Bicycle Thieves and Rome, Open City are centered rather around the humanist messages and the poetry within them. By contrast, it's hard nearly half a century later to view Pasolini's debut feature, Accattone, without recognising it as being an angry message film, with enough political vitriol to still seem a bit unsettling and radical.

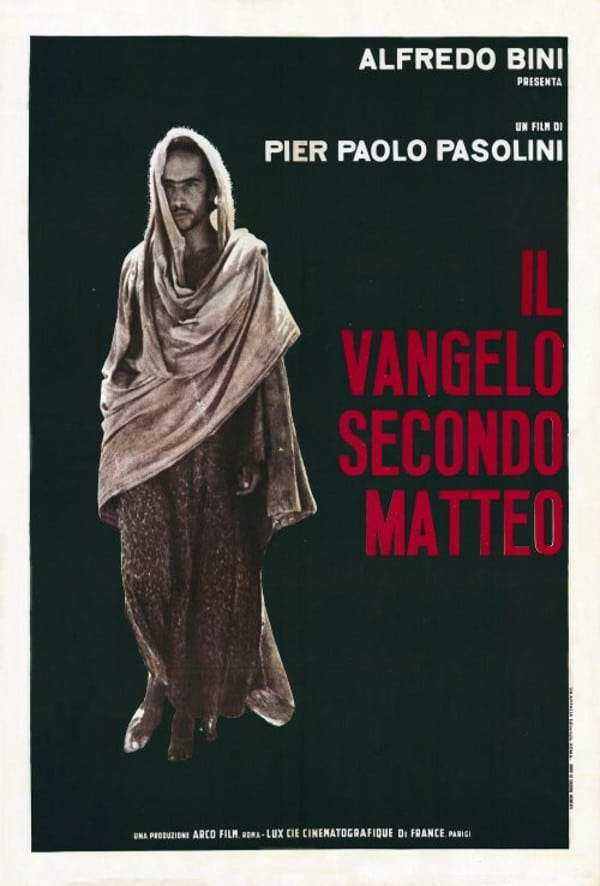

The director's third feature had the potential to be his most controversial yet, particularly after his arrest on blasphemy charges related to his segment of the omnibus Ro.Go.Pa.G. - an adaptation of the life of Jesus Christ monolithically titled The Gospel According to St. Matthew. Yet the film turned out to be the furthest thing possible from an anti-religious screed; in its perfectly unassuming way, it might even be the most devout of all filmic depictions of Christ's gospel, doubly surprising given that Pasolini was a non-believer (though one who described himself as a non-believer with a nostalgia for belief). Which is not to say that it isn't also a perfect vehicle for the director's political beliefs.

There is one single choice that Pasolini made that sets his film apart from every other biblical epic I can name: he elected to present the material precisely as it appears in the Bible, adding nothing and taking nothing away, and filming in the least-intrusive way he could manage. His launching point was the second Gospel of the New Testament, selected because he found Mark too vulgar, Luke too sentimental, and John too mystic (a polite way of saying "weird and problematic", maybe). And in Matthew's Jesus, Pasolini found a man of action and impatience, inclined to force his message rather than too subtly hint at it until people figured out what he meant.

In essence, Pasolini found in the biblical Christ history's very first socialist revolutionary, a man who preached the renunciation of worldly things and the love of all mankind at the expense of the personal good. I do not know if this was his motivation in first making the film; by some accounts, he discovered to his surprise that the finished project reflected his own views more than the views he thought he was reading in the biblical text. Either way, the idea of a proto-Marxist Christ means that no matter how strange Matthew may seem in relationship to the rest of Pasolini's early work - a period piece rather than a story of contemporary Italy, a work proclaiming God's triumph instead of cynical materialism - it still fits quite comfortably into Pasolini's career, and the overarching narrative of Italian cinema in the decades after World War II.

I would not take this line of thinking any further; that Matthew is patently sympathetic to Pasolini's Marxism is widely understood. Besides, if that were all the film had to offer, it would be nothing but a polemic, and I can't stand polemics. What rather amazes me about Matthew is how beautifully it retells a spiritual story - which, bear in mind, is a story I have absolutely no personal stake in - using a fairly simple visual language, and without resorting to the diffused lighting and overbearing piousness that makes most American Bible films such well-intentioned slogs.

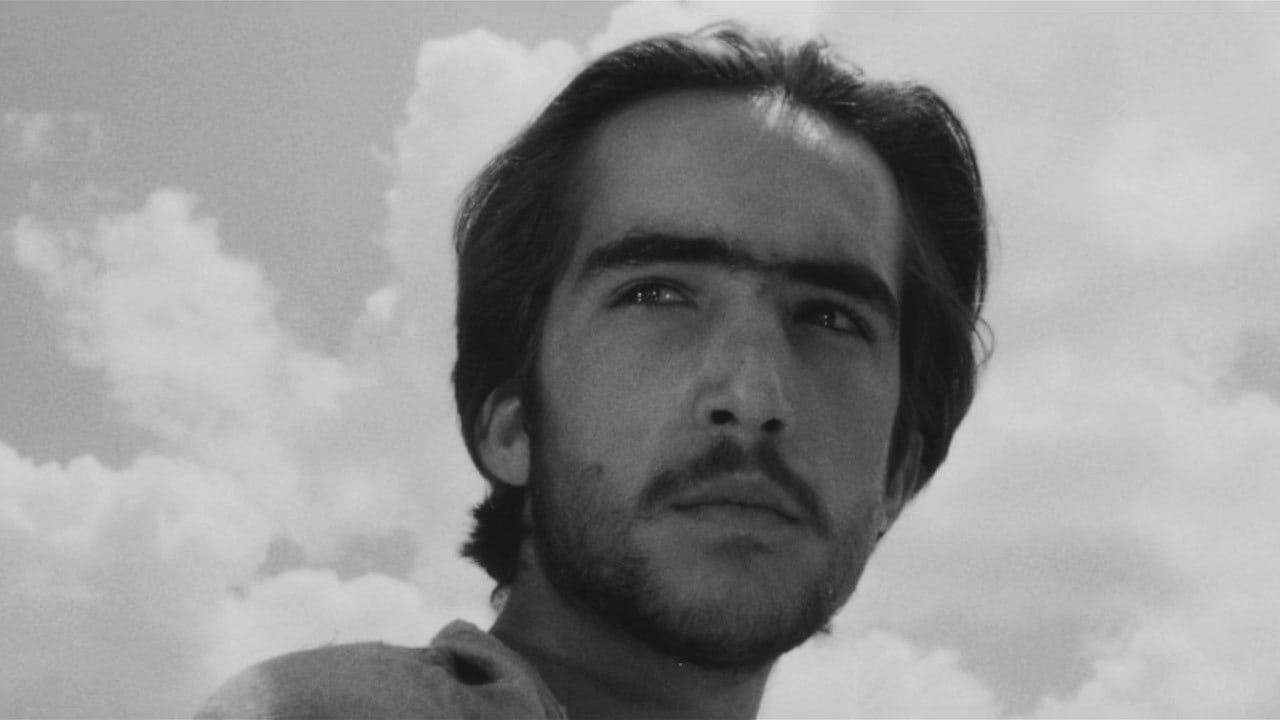

When I call the film simple, I don't mean to imply anything bad about Pasolini's skill, nor the skill of his cinematographer, Tonino Delli Colli, and even less so his editor, Nino Baragli. In fact, Matthew is a tremendously strong visual work, and it continues to impress me about Pasolini that, even if his themes were more important to him than his craft (and I've always gotten that impression from everything he said about filmmaking during his life), he is an extremely gifted visual storyteller. Pasolini's filmmaking style is marked by an exceptionally fluid roving camera, with long tracking shots through space and across groups of people punctuated by just-as-long still images of a person or object. In Matthew, the still shots tend to be focused on Jesus's own face, wonderfully embodied by a Spanish economics student named Enrique Irazoqui, who in the finest Neo-Realist tradition was cast when Pasolini realised that the young man looked exactly like his own mind's-eye version of Christ.

The visual aspect of Matthew focuses above all things on the presence of Christ, his physicality and his actions; this is why it is so very unlike most other movies of this type. When it is possible to keep something simple and direct, Pasolini will make that choice, and it is always in the best interest both of his own ideological aim, and the theological import of his film. Unlike so many filmmakers driven by religious fervor, Pasolini is not interested in the mysteries of faith; to him, there isn't a mystery, if we accept that Jesus Christ existed, and performed the miracles ascribed to him. When he shows Christ walking on the water, that's all it is: not a tremendous moment of exultation, but a man who is the embodiment of God's power doing something that only God could do. The film is altogether straightforward about these things, and by taking the strange majesty out of Christ, Pasolini stresses the human element in Christ's work and teachings, a human element that is perhaps forgotten sometimes.

As an example, let us compare how Pasolini films the crucifixion with the same event as presented in the most important modern religious film, Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ. In Gibson's hands, this event is huge and noisy, full of CGI and slow-motion, dramatic shots of raindrops, weirdly esoteric angles, and in general a sense of ultimate Bigness. In Pasolini's film, a man is hanging on a cross, he dies, the camera shakes to signify the earthquake, and the man's body is taken down, in a mere fraction of the shots Gibson used. And yet, the moment is more powerful in Pasolini's work. Now, a part of this is certainly because Pasolini's film has been about human characters, while Gibson's is flat-out torture porn (though, to be fair, the most technically accomplished torture porn ever made). But the directness and simplicity of Pasolini's approach speaks to what I think is his trust in the material; whereas Gibson wants to stress that something very important is happening, Pasolini allows the story to speak for itself. And given that everyone seeing either of those films doubtlessly knows about the importance of the crucifixion going into it, Pasolini's seems ultimately much less heavy-handed and much simpler and truer.

Of course, I'm just an atheist, talking out of my ass. All I know is this: when I watch The Gospel According to St. Matthew, I am moved and inspired in a way that no other religious drama has done. And I think this is because Pasolini grasps an important truth that, for whatever reason, seems to elude other filmmakers: Christ was the Son of Man, God made flesh in the world so that he could relate to humanity on our own level. His story is an essentially human one, concerned with matters of the spirit but grounded in matters of earth. By presenting that story without editorialising, and stressing the human scale of the thing rather than its bombastic religious import, Pasolini (nostalgic unbeliever that he is) managed to make a nearly-perfect cinematic summary of why Christ's words are important to we who live in the world.

Today, we meet the director long before those days of his most terrible reputation, in 1964. In the earlier parts of his career, Pasolini was naught but a Neo-Realist, continuing the post-war tradition of Vittorio De Sica and Roberto Rossellini in making pseudo-documentary films about the crushing condition of impoverished life in Italy. Even in these first films, Pasolini could never be mistaken for anything but a controversialist; while the filmmakers of the generation before him were regarded in their own day as the next things to Communists, the modern reputation of Bicycle Thieves and Rome, Open City are centered rather around the humanist messages and the poetry within them. By contrast, it's hard nearly half a century later to view Pasolini's debut feature, Accattone, without recognising it as being an angry message film, with enough political vitriol to still seem a bit unsettling and radical.

The director's third feature had the potential to be his most controversial yet, particularly after his arrest on blasphemy charges related to his segment of the omnibus Ro.Go.Pa.G. - an adaptation of the life of Jesus Christ monolithically titled The Gospel According to St. Matthew. Yet the film turned out to be the furthest thing possible from an anti-religious screed; in its perfectly unassuming way, it might even be the most devout of all filmic depictions of Christ's gospel, doubly surprising given that Pasolini was a non-believer (though one who described himself as a non-believer with a nostalgia for belief). Which is not to say that it isn't also a perfect vehicle for the director's political beliefs.

There is one single choice that Pasolini made that sets his film apart from every other biblical epic I can name: he elected to present the material precisely as it appears in the Bible, adding nothing and taking nothing away, and filming in the least-intrusive way he could manage. His launching point was the second Gospel of the New Testament, selected because he found Mark too vulgar, Luke too sentimental, and John too mystic (a polite way of saying "weird and problematic", maybe). And in Matthew's Jesus, Pasolini found a man of action and impatience, inclined to force his message rather than too subtly hint at it until people figured out what he meant.

In essence, Pasolini found in the biblical Christ history's very first socialist revolutionary, a man who preached the renunciation of worldly things and the love of all mankind at the expense of the personal good. I do not know if this was his motivation in first making the film; by some accounts, he discovered to his surprise that the finished project reflected his own views more than the views he thought he was reading in the biblical text. Either way, the idea of a proto-Marxist Christ means that no matter how strange Matthew may seem in relationship to the rest of Pasolini's early work - a period piece rather than a story of contemporary Italy, a work proclaiming God's triumph instead of cynical materialism - it still fits quite comfortably into Pasolini's career, and the overarching narrative of Italian cinema in the decades after World War II.

I would not take this line of thinking any further; that Matthew is patently sympathetic to Pasolini's Marxism is widely understood. Besides, if that were all the film had to offer, it would be nothing but a polemic, and I can't stand polemics. What rather amazes me about Matthew is how beautifully it retells a spiritual story - which, bear in mind, is a story I have absolutely no personal stake in - using a fairly simple visual language, and without resorting to the diffused lighting and overbearing piousness that makes most American Bible films such well-intentioned slogs.

When I call the film simple, I don't mean to imply anything bad about Pasolini's skill, nor the skill of his cinematographer, Tonino Delli Colli, and even less so his editor, Nino Baragli. In fact, Matthew is a tremendously strong visual work, and it continues to impress me about Pasolini that, even if his themes were more important to him than his craft (and I've always gotten that impression from everything he said about filmmaking during his life), he is an extremely gifted visual storyteller. Pasolini's filmmaking style is marked by an exceptionally fluid roving camera, with long tracking shots through space and across groups of people punctuated by just-as-long still images of a person or object. In Matthew, the still shots tend to be focused on Jesus's own face, wonderfully embodied by a Spanish economics student named Enrique Irazoqui, who in the finest Neo-Realist tradition was cast when Pasolini realised that the young man looked exactly like his own mind's-eye version of Christ.

The visual aspect of Matthew focuses above all things on the presence of Christ, his physicality and his actions; this is why it is so very unlike most other movies of this type. When it is possible to keep something simple and direct, Pasolini will make that choice, and it is always in the best interest both of his own ideological aim, and the theological import of his film. Unlike so many filmmakers driven by religious fervor, Pasolini is not interested in the mysteries of faith; to him, there isn't a mystery, if we accept that Jesus Christ existed, and performed the miracles ascribed to him. When he shows Christ walking on the water, that's all it is: not a tremendous moment of exultation, but a man who is the embodiment of God's power doing something that only God could do. The film is altogether straightforward about these things, and by taking the strange majesty out of Christ, Pasolini stresses the human element in Christ's work and teachings, a human element that is perhaps forgotten sometimes.

As an example, let us compare how Pasolini films the crucifixion with the same event as presented in the most important modern religious film, Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ. In Gibson's hands, this event is huge and noisy, full of CGI and slow-motion, dramatic shots of raindrops, weirdly esoteric angles, and in general a sense of ultimate Bigness. In Pasolini's film, a man is hanging on a cross, he dies, the camera shakes to signify the earthquake, and the man's body is taken down, in a mere fraction of the shots Gibson used. And yet, the moment is more powerful in Pasolini's work. Now, a part of this is certainly because Pasolini's film has been about human characters, while Gibson's is flat-out torture porn (though, to be fair, the most technically accomplished torture porn ever made). But the directness and simplicity of Pasolini's approach speaks to what I think is his trust in the material; whereas Gibson wants to stress that something very important is happening, Pasolini allows the story to speak for itself. And given that everyone seeing either of those films doubtlessly knows about the importance of the crucifixion going into it, Pasolini's seems ultimately much less heavy-handed and much simpler and truer.

Of course, I'm just an atheist, talking out of my ass. All I know is this: when I watch The Gospel According to St. Matthew, I am moved and inspired in a way that no other religious drama has done. And I think this is because Pasolini grasps an important truth that, for whatever reason, seems to elude other filmmakers: Christ was the Son of Man, God made flesh in the world so that he could relate to humanity on our own level. His story is an essentially human one, concerned with matters of the spirit but grounded in matters of earth. By presenting that story without editorialising, and stressing the human scale of the thing rather than its bombastic religious import, Pasolini (nostalgic unbeliever that he is) managed to make a nearly-perfect cinematic summary of why Christ's words are important to we who live in the world.