In the realm of Story

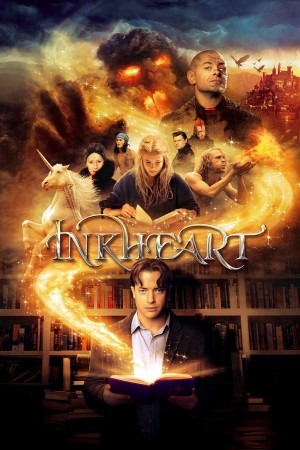

Inkheart isn't ultimately a good movie, but it comes much closer than any Brendan Fraser starring vehicle should be able to. Indeed, for a solid thirty minutes, it's a much more than serviceable family-friendly adventure fantasy, and it's only once the plot starts to tie itself in knots trying to avoid ending ahead of time that it becomes impossible to ignore how very slack the whole feature is, in the hands of the competent but highly unimaginative director Iain Softley (of. among others, Backbeat, Hackers, and K-PAX - and how very strange is it that all these films share one guiding hand?).

In brief, the film, adapted by David Lindsay-Abaire from a children's novel that I've never heard of, though it is apparently quite successful, Inkheart is about Mortimer Folchart (Fraser), a "silvertongue", someone who can draw the characters in a book out into the real world by reading aloud. We meet him shortly before he learns that he possesses this gift; we see him for the second time twelve years later, when he plainly knows enough to be borderline paranoid about his talent; there is clearly an Unfortunate Event in his past, though it takes a while for us and his teenage daughter, Meggie (Eliza Hope Bennett) to learn precisely what that is.

Yes, "Meggie." For most of the film, I thought I was just mishearing it, or maybe that Fraser was talking funny. Nope, the end credits confirm it. "Meggie". Presumably short for "Megan", although that doesn't justify it one damned bit.

Anyway, to cut to the chase, Mortimer and Meggie find themselves battling Capricorn (Andy Serkis), a villain from the out-of-print novel Inkheart that Mo released once upon a time. Helping, mostly, is Dustfinger (Paul Bettany), another Inkheart character who wants desperately to get back into the novel, and Elinor (Helen Mirren), the aunt of Mo's missing wife, a rare book collector and crazy old lady who wears turbans. Helping out even less is the book's retired author Fenoglio (Jim Broadbent), who exists almost solely to stretch out the film for a wildly unnecessary plot tangent that kicks in after about one hour (by the way, what kind of filmmaker would put Mirren and Broadbent in a film together, and then never use them in the same scene - this is a filmmaker who's no friend of mine).

Here's the thing: Inkheart is nonsensical long before it becomes a problem that it's nonsensical. The central mechanism by which literary characters come to life doesn't hold up to even the slightest scrutiny, and the more we learn about it, the more it's riddled with logical inconsistencies and unanswered questions. The silvertongue magic doesn't just bring characters to life, it actually removes living figures from the world of their book; does this mean that anyone in the world who picks up a copy of that book will find the character missing? It certainly doesn't seem that way, but if the book-reality has any meaning at all, it feels like that should be the case (and it cannot be explained away by saying that they're missing from that particular copy of the book, given how many different versions of Inkheart are seen to exist). For that matter, we learn that Mo can't simply call a character to life; they have to be swapped-out by somebody in the real world. But there's no indication that the content of the books change as a result, even though the swapped individuals remain in the book's world. And to top it all off, the extremely obvious idea that the silvertongue could read from any narrative, even a newly written one, is never floated by any character at any point, even when it would be terrifically useful to introduce a short story with, for instance, Alana the Skeleton Key Fairy; this idea, which occurred to me almost immediately, isn't brought into play until it's time for the "let's use a whopping deus ex machina to resolve everything" climax.

Yet, despite the very real fact of all these plot holes, the film is for a long time quite imaginative and seductive enough that I didn't care to pick at them. Iain Softley may be a hack, but he's not a particularly talentless one, and for a while, Inkheart has a magical touch to it that promises to end in one of the best kiddie fantasies in recent years. The best scene in the film, in which Mo and Meggie drift around an outdoor old book market in Switzerland, as Mo starts to hear the books talking to him, begging to be read, is a small masterpiece, expressing exactly what it is about old books that is so marvelously appealing, and even if the story's ultimate message seems to be, "Hey kids, reading can endanger the lives of you and everyone you love!" there's an undercurrent throughout about just how great books are, with their smells and textures.

The cast is reasonably good, even when they have unplayable material: Fraser gives his best performance since I don't know when, powerfully reminding us that he can be a really appealling everyman hero when he wants to be, while Mirren is customarily delightful in a role that asks her to swan about and be dramatic. The real standout is Bennett, holding her own against a passle of well-known faces and never lapsing into the role's cloying margins, even if she's obviously a couple of years older than the character. No matter how little sense the film makes - and by the end, it makes absolutely no sense at all - the actors always manage to keep it firmly in the realm of the humane. It's a pity that Inkheart descends so deeply into a narrative muddle, and God knows there's no great craftsmanship to keep it interesting to look at while that implosion occurs (though Javier Navarette's score is unexpectedly deep and inventive, not at all the trite adventure music that one would anticipate), because there are moments of absolute wonder to be had. Just not enough to make the film anything more than a painless misfire, when all is said and done.

5/10

In brief, the film, adapted by David Lindsay-Abaire from a children's novel that I've never heard of, though it is apparently quite successful, Inkheart is about Mortimer Folchart (Fraser), a "silvertongue", someone who can draw the characters in a book out into the real world by reading aloud. We meet him shortly before he learns that he possesses this gift; we see him for the second time twelve years later, when he plainly knows enough to be borderline paranoid about his talent; there is clearly an Unfortunate Event in his past, though it takes a while for us and his teenage daughter, Meggie (Eliza Hope Bennett) to learn precisely what that is.

Yes, "Meggie." For most of the film, I thought I was just mishearing it, or maybe that Fraser was talking funny. Nope, the end credits confirm it. "Meggie". Presumably short for "Megan", although that doesn't justify it one damned bit.

Anyway, to cut to the chase, Mortimer and Meggie find themselves battling Capricorn (Andy Serkis), a villain from the out-of-print novel Inkheart that Mo released once upon a time. Helping, mostly, is Dustfinger (Paul Bettany), another Inkheart character who wants desperately to get back into the novel, and Elinor (Helen Mirren), the aunt of Mo's missing wife, a rare book collector and crazy old lady who wears turbans. Helping out even less is the book's retired author Fenoglio (Jim Broadbent), who exists almost solely to stretch out the film for a wildly unnecessary plot tangent that kicks in after about one hour (by the way, what kind of filmmaker would put Mirren and Broadbent in a film together, and then never use them in the same scene - this is a filmmaker who's no friend of mine).

Here's the thing: Inkheart is nonsensical long before it becomes a problem that it's nonsensical. The central mechanism by which literary characters come to life doesn't hold up to even the slightest scrutiny, and the more we learn about it, the more it's riddled with logical inconsistencies and unanswered questions. The silvertongue magic doesn't just bring characters to life, it actually removes living figures from the world of their book; does this mean that anyone in the world who picks up a copy of that book will find the character missing? It certainly doesn't seem that way, but if the book-reality has any meaning at all, it feels like that should be the case (and it cannot be explained away by saying that they're missing from that particular copy of the book, given how many different versions of Inkheart are seen to exist). For that matter, we learn that Mo can't simply call a character to life; they have to be swapped-out by somebody in the real world. But there's no indication that the content of the books change as a result, even though the swapped individuals remain in the book's world. And to top it all off, the extremely obvious idea that the silvertongue could read from any narrative, even a newly written one, is never floated by any character at any point, even when it would be terrifically useful to introduce a short story with, for instance, Alana the Skeleton Key Fairy; this idea, which occurred to me almost immediately, isn't brought into play until it's time for the "let's use a whopping deus ex machina to resolve everything" climax.

Yet, despite the very real fact of all these plot holes, the film is for a long time quite imaginative and seductive enough that I didn't care to pick at them. Iain Softley may be a hack, but he's not a particularly talentless one, and for a while, Inkheart has a magical touch to it that promises to end in one of the best kiddie fantasies in recent years. The best scene in the film, in which Mo and Meggie drift around an outdoor old book market in Switzerland, as Mo starts to hear the books talking to him, begging to be read, is a small masterpiece, expressing exactly what it is about old books that is so marvelously appealing, and even if the story's ultimate message seems to be, "Hey kids, reading can endanger the lives of you and everyone you love!" there's an undercurrent throughout about just how great books are, with their smells and textures.

The cast is reasonably good, even when they have unplayable material: Fraser gives his best performance since I don't know when, powerfully reminding us that he can be a really appealling everyman hero when he wants to be, while Mirren is customarily delightful in a role that asks her to swan about and be dramatic. The real standout is Bennett, holding her own against a passle of well-known faces and never lapsing into the role's cloying margins, even if she's obviously a couple of years older than the character. No matter how little sense the film makes - and by the end, it makes absolutely no sense at all - the actors always manage to keep it firmly in the realm of the humane. It's a pity that Inkheart descends so deeply into a narrative muddle, and God knows there's no great craftsmanship to keep it interesting to look at while that implosion occurs (though Javier Navarette's score is unexpectedly deep and inventive, not at all the trite adventure music that one would anticipate), because there are moments of absolute wonder to be had. Just not enough to make the film anything more than a painless misfire, when all is said and done.

5/10