Hooker with a heart of gold: The early years

Street Angel was Frank Borzage's 1928 follow-up to his masterful 7th Heaven; but it honestly feels much more like his follow-up to F.W. Murnau's Sunrise. The earlier films were of course produced concurrently, and while 7th Heaven has some distinct sympathies with Murnau's style, it's got nothing on Street Angel, which was produced after Sunrise was completed, at a time when William Fox was actively encouraging ("requiring" is probably too strong a word) his directors to look to that movie as the apex of the cinematic arts. So it's not really all that surprising that Borzage and his crew (most importantly, DP Ernest Palmer and art director Harry Oliver) would find themselves mimicking Sunrise fearlessly, incorporating some shots that straddle the line between "influenced by" and "stealing from".

The result is a film that draws from the finest elements of two extraordinary movies, and ends up falling short of both of them. Certainly, Street Angel is a good movie, even a great movie, but it lacks the awesome cohesiveness of Borzage's previous film. If I had to put it in words, I'd say that Street Angel is full of exceptional camerawork and imagery that aren't there because they're necessary, but because Murnau had done them so well already. This feeling is aggravated a bit by a certain stylistic imbalance within the film itself; it's split down the middle between the proto poetic realism that Borzage had enjoyed such success with, and straight-up German Expressionism. By the end, Street Angel has settled firmly on the side of Expressionism, to its benefit: the last thirty minutes of the film are by far its most successful. Until then, we're treated to the curious spectacle of a well-made movie that can't quite decide exactly what kind of movie it would like to be.

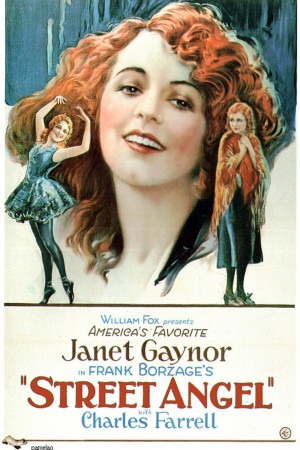

Set in Naples, sometime in the 1920s, Street Angel follows the tragic case of Angela (Janet Gaynor), whose sick mother will surely die without medicine. Lacking money, Angela reluctantly turns to prostitution, one of the town's most successful industries; but when her innocence and disgust for the work leaves her unable to make money turning tricks, she tries to steal some food, and is caught red-handed. For the crime of "robbery while soliciting", she is sentenced to one year in the workhouses. Thankfully, the Neapolitan police are unusually bad, and she escapes in mere hours to find that her mother has already died. With nothing left to keep her in Naples, she hides from the cops with the help of a circus troupe, and leaves the city.

Angela becomes a tightrope walker, and a damned good one. One day during the circus's travels, she meets a wandering painter named Gino (Charles Farrell), for whom she instantly develops the kind of hatred that really means she loves him. A little while later, an accident leaves her unable to continue her work, leaving her free to end up with Gino to start a household, and to inspire him to create his greatest paintings using her as his angelic model. Unfortunately, there comes a time when he wants to go to Naples, where a painter of his talents can find real success, and Angela, not wanting to tell him that she's a wanted fugitive in that city and certainly not wanting to tell him why, goes along. In short order, she's been apprehended, he finds out that she's a thieving whore, and he spends a year trying to banish her from his mind while she spends the same year looking to a bright future with him as the only thing sustaining her throughout her imprisonment.

Once again, Borzage proved himself exceptionally adept at turning a musty potboiler into rich human drama, aided considerably by his great leads. Their chemistry isn't quite so perfect as it was in 7th Heaven, though their individual performances are: Farrell probably gives a stronger performance her than in that film, in fact, particularly in the later stages when he's convinced that Angela has betrayed him. And if Gaynor isn't operating on quite the same superhuman level that she did in 7th Heaven and Sunrise, somewhat due to a script that give her less demanding emotions to work with, it's still not hard to see why she was cited for all three films in receiving the first-ever Best Actress Oscar. The core of the story may be simple to the point of inanity - a guy thinks the woman he loves is bad, but she is not - but Gaynor and Farrell are both impossibly alive in their roles, giving the kind of tremendously human melodramatic performances that could only exist for a few years late in the silent era.

But everything else... I'm not quite sure what to say. The easiest thing is to praise the definitive turn towards Expressionism that the film takes once Angela has been captured by the police for the second time, and we see the workhouse as a monstrous steaming dungeons of shadows and sharp edges; Gino's lonely life as a painter with passionless affairs is represented with flat and bleak compositions; and the lover's reunion, which first erupts in violence before returning to affection, is shown in a foggy sequence that oozes atmospheric mise en scène, while also boasting some of the finest construction of any scene I can think of in the 1920s; it is easily the best single sequence I have seen in any of Borzage's films.

Until that point, though, the film struggles a bit to find an identity. Everything involving Angela's relationship with her poverty and the police chasing her is shown using Expressionist tricks like gigantic shadows and forced-perspective angles; once she arrives with the circus and falls in love with Gino, things start to adopt a look of pastoral realism. I understand the theoretical point behind all of this, but I'm not entirely certain that it works as Borzage intended: the poetic style that made 7th Heaven a masterpiece almost seems like an accident or a mistake in this film. Expressionism, perhaps, is too strong a style to mix with more normal modes of filmmaking, unless it be as a dream sequence or surreal interlude. Murnau made this clash work in Sunrise, arguably, but then again there's not much in that film that isn't Expressionist; and Murnau was a towering genius, whereas Borzage is simply an extraordinarily gifted filmmaker. At any rate, the central sequences, involving Angela and Gino's blossoming love and Gino's rise to artistic prominence, rely a bit more on the actors' natural appeal and less on the skills behind the camera than ws the case in 7th Heaven, and this cannot help but make the film a bit less impressive than its forebear.

On the other hand, what am I really saying here? I joked with a friend recently that he shouldn't get too excited about 7th Heaven, because it wasn't as good as Sunrise (like anything could be); and the more I write, the more I realise that my argument is coming down to "Street Angel isn't as good as 7th Heaven" - like I really expected it to be. It's still top-drawer filmmaking, with characteristically bold tracking shots and a roiling melodrama that hits upon more human truths than most movies even aim for. It's just not one of the defining films of its era, and if that's a disappointment, it's only because the masterpieces of 1927 have apparently spoiled me for all other movies.

The result is a film that draws from the finest elements of two extraordinary movies, and ends up falling short of both of them. Certainly, Street Angel is a good movie, even a great movie, but it lacks the awesome cohesiveness of Borzage's previous film. If I had to put it in words, I'd say that Street Angel is full of exceptional camerawork and imagery that aren't there because they're necessary, but because Murnau had done them so well already. This feeling is aggravated a bit by a certain stylistic imbalance within the film itself; it's split down the middle between the proto poetic realism that Borzage had enjoyed such success with, and straight-up German Expressionism. By the end, Street Angel has settled firmly on the side of Expressionism, to its benefit: the last thirty minutes of the film are by far its most successful. Until then, we're treated to the curious spectacle of a well-made movie that can't quite decide exactly what kind of movie it would like to be.

Set in Naples, sometime in the 1920s, Street Angel follows the tragic case of Angela (Janet Gaynor), whose sick mother will surely die without medicine. Lacking money, Angela reluctantly turns to prostitution, one of the town's most successful industries; but when her innocence and disgust for the work leaves her unable to make money turning tricks, she tries to steal some food, and is caught red-handed. For the crime of "robbery while soliciting", she is sentenced to one year in the workhouses. Thankfully, the Neapolitan police are unusually bad, and she escapes in mere hours to find that her mother has already died. With nothing left to keep her in Naples, she hides from the cops with the help of a circus troupe, and leaves the city.

Angela becomes a tightrope walker, and a damned good one. One day during the circus's travels, she meets a wandering painter named Gino (Charles Farrell), for whom she instantly develops the kind of hatred that really means she loves him. A little while later, an accident leaves her unable to continue her work, leaving her free to end up with Gino to start a household, and to inspire him to create his greatest paintings using her as his angelic model. Unfortunately, there comes a time when he wants to go to Naples, where a painter of his talents can find real success, and Angela, not wanting to tell him that she's a wanted fugitive in that city and certainly not wanting to tell him why, goes along. In short order, she's been apprehended, he finds out that she's a thieving whore, and he spends a year trying to banish her from his mind while she spends the same year looking to a bright future with him as the only thing sustaining her throughout her imprisonment.

Once again, Borzage proved himself exceptionally adept at turning a musty potboiler into rich human drama, aided considerably by his great leads. Their chemistry isn't quite so perfect as it was in 7th Heaven, though their individual performances are: Farrell probably gives a stronger performance her than in that film, in fact, particularly in the later stages when he's convinced that Angela has betrayed him. And if Gaynor isn't operating on quite the same superhuman level that she did in 7th Heaven and Sunrise, somewhat due to a script that give her less demanding emotions to work with, it's still not hard to see why she was cited for all three films in receiving the first-ever Best Actress Oscar. The core of the story may be simple to the point of inanity - a guy thinks the woman he loves is bad, but she is not - but Gaynor and Farrell are both impossibly alive in their roles, giving the kind of tremendously human melodramatic performances that could only exist for a few years late in the silent era.

But everything else... I'm not quite sure what to say. The easiest thing is to praise the definitive turn towards Expressionism that the film takes once Angela has been captured by the police for the second time, and we see the workhouse as a monstrous steaming dungeons of shadows and sharp edges; Gino's lonely life as a painter with passionless affairs is represented with flat and bleak compositions; and the lover's reunion, which first erupts in violence before returning to affection, is shown in a foggy sequence that oozes atmospheric mise en scène, while also boasting some of the finest construction of any scene I can think of in the 1920s; it is easily the best single sequence I have seen in any of Borzage's films.

Until that point, though, the film struggles a bit to find an identity. Everything involving Angela's relationship with her poverty and the police chasing her is shown using Expressionist tricks like gigantic shadows and forced-perspective angles; once she arrives with the circus and falls in love with Gino, things start to adopt a look of pastoral realism. I understand the theoretical point behind all of this, but I'm not entirely certain that it works as Borzage intended: the poetic style that made 7th Heaven a masterpiece almost seems like an accident or a mistake in this film. Expressionism, perhaps, is too strong a style to mix with more normal modes of filmmaking, unless it be as a dream sequence or surreal interlude. Murnau made this clash work in Sunrise, arguably, but then again there's not much in that film that isn't Expressionist; and Murnau was a towering genius, whereas Borzage is simply an extraordinarily gifted filmmaker. At any rate, the central sequences, involving Angela and Gino's blossoming love and Gino's rise to artistic prominence, rely a bit more on the actors' natural appeal and less on the skills behind the camera than ws the case in 7th Heaven, and this cannot help but make the film a bit less impressive than its forebear.

On the other hand, what am I really saying here? I joked with a friend recently that he shouldn't get too excited about 7th Heaven, because it wasn't as good as Sunrise (like anything could be); and the more I write, the more I realise that my argument is coming down to "Street Angel isn't as good as 7th Heaven" - like I really expected it to be. It's still top-drawer filmmaking, with characteristically bold tracking shots and a roiling melodrama that hits upon more human truths than most movies even aim for. It's just not one of the defining films of its era, and if that's a disappointment, it's only because the masterpieces of 1927 have apparently spoiled me for all other movies.

Categories: love stories, silent movies, trash and melodrama