A matter of taste

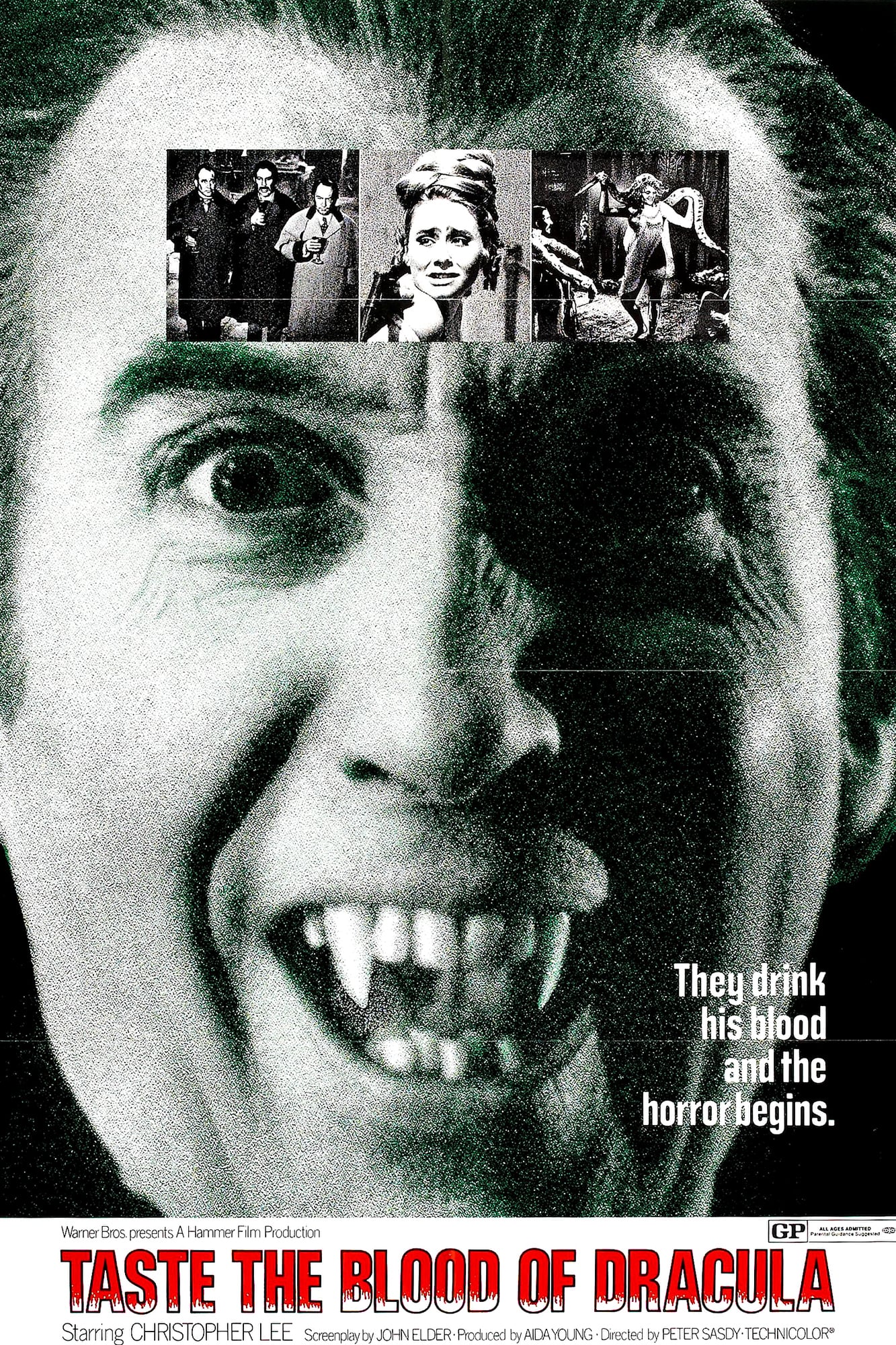

By the time that Dracula Has Risen from the Grave was released in 1968, the Hammer horror film was already looking a tad musty; and that watershed year only strengthened the impression that there was something fundamentally old-fashioned about the studio's moody Gothic pictures in the age of Night of the Living Dead. That didn't keep Risen from the Grave from turning a profit, leaving the studio anxious to keep the franchise running, signs of age be damned - although Taste the Blood of Dracula, released in the summer of 1970, ended up being a fairly self-conscious and often very weird attempt by the studio to do something about that liberated youth culture that everybody had been talking about for a while. It wouldn't stay that way for long, but Taste the Blood is easily the strangest and most confused of the Dracula films up to that point, and the first of Hammer's vampire films where the bad elements seriously threaten to outnumber the good.

You wouldn't know that from the film's knock-out opening, though: in a coach traveling through the Carpathian woods, a boisterous British merchant named Weller (Roy Kinnear) is busy bragging to his unwilling companions about all the marvelous things he has acquired on his recent trip. Eventually, he mentions that he's on his way to Karlsberg (another place-name that hasn't, technically, appeared in any of the films yet), and just hearing the name of that town is enough to make one of his seatmates, suffering from a mental disorder of some kind, go into crazed spasms - and to throw Weller out of the coach.

Thus left without transportation, Weller burrows his way through the increasingly threatening woods, ultimately hearing a terrifying scream not that far from his own location. Going to check it out, what should he see but the final scene from Risen from the Grave, with Count Dracula pinned by a crucifix and writhing in agony as he bleeds out all over the ground. When the merchant finally works up the courage to go and check things out, the vampire's blood has turned into red powder, something that Weller finds much more fascinating than anything. Cue credits.

This is where the weird part kicks in. The story now jumps to London - the first time that any of Hammer's Dracula films have so much as referenced that city, where Bram Stoker's novel originally took place - where a bullying demagogue named William Hargood (Geoffrey Keen) is screaming at his daughter Alice (Linda Hayden) for her unspeakably wanton behavior at church that morning - flirting with a man, if you can believe such horrors. The young man in question, Paul Paxton (Anthony Higgins), seems nice enough, and Alice asks her mother (Gwen Watford) if there's some reason that Paul's father might have offended Hargood. Neither mother nor daughter has any explanation, but we get to find out very presently that the answer is quite different: under the excuse that it's time for his monthly charity trip to the East End, Hargood jumps into a cab where he meets none other than Samuel Paxton (Peter Sallis), and they're ultimately joined by a certain Jonathon Secker (John Carson). Their destination is in the East End, sure enough, but it's not charity work on their mind - it's a very private, high-class bordello. There they watch as a half naked woman cavorts with a snake, as beautiful girls without tops lounge on their arms (we get the first nipples in the series in this scene; and there's something inherently shocking about seeing nudity on that quintessentially '60s film stock, even now), and other tremendously low-key things that would have been unthinkably saucy in Victorian England.

The three men have enjoyed this routine for a while; long enough, anyay, to get bored with it. So they're more curious than angry when notorious rakehell Lord Courtley (Ralph Bates, in what was inteneded to have been his star-making role; see below) sweeps in and takes their women. Their curiosity leads them to invite the young lord out to dinner, where they approach him in an oh-so-circumspect way about introducing them to the kinkier pleasures, and he responds by taking them to Weller's store, where the merchant has for sale the cape and clasp of a certain Count Dracula, along with a box full of red powder. Courtley has apparently been eyeing this prize for some while, but never had enough money; but with three important gentlemen paying his way, he'll finally get his chance. After some dithering, the deal is made and Courtley takes the three men to his family crypt, decked out in the trappings of a black mass (somewhat unbelievably, this is all still the same evening). One elaborate ritual involving Courtley's blood later, all four men are holding goblets of the foaming, reconstituted blood of Dracula; the older gentlemen are reluctant to drink something so foul (it looks exactly like V-8, for the record), and it turns out that they're right: when Courtley downs his goblet, he starts spasming and falls to the ground, dead. The three men tear ass back to their homes where they order their wives and children to provide their alibis.

Now, here's a little story. Apparently Hammer wasn't initially interested in bringing Christopher Lee back as the count this time - the story was meant to use Dracula as an absent threat, sort of like Brides of Dracula, and Lord Courtley was to have been the main villain, in a sort of debutante's ball for Bates. But Warner Bros. stepped in and informed Hammer that if the Brits wanted American distribution, they'd damn well better have Dracula in their Dracula picture, leading studio head Anthony Hinds to quickly revise the back half of his screenplay. Meanwhile, Hammer was able to convince Chris Lee to come back to the role that he hated so very goddamn much for what was, by Hammer standards, a quite generous sum. This didn't keep Lee from bitching, of course, because if there's one thing he hated, it was playing Count Dracula. He hated it so much, that not only did he star in two Dracula films for Hammer in 1970, he also played the character in a Jesus Franco film titled Count Dracula. Basically, my point is that incriminating photos of Christopher Lee must be one of the things they give you when you join the horror filmmakers' union.

So, when Courtley turns into Dracula, as he must, the revived count waxes wroth at these three men who killed his disciple - despite the fact that Dracula never in his unlife ever laid eyes on Courtley. At any rate, it's enough of an offense for the vampire to declare vengeance upon the three gentlemen, and for the second film in a row, all I can do is sputter and ask: isn't revenge such a petty thing for the Lord of the Undead?

At least his scheme is fairly outré: enslave the men's children and force them to kill their fathers. True, it's not the same thing as having Dracula actually out doing the killing himself, and it reduces most of Lee's performance to standing in the shadows and counting down the number of men left to die (but you know what, nobody can stand and intone threatening lines quite like Christopher Lee). It's likely an artifact of the last-minute rewrite, bringing Dracula in unexpectedly; at any rate, it ties off the film's themes in a neat bow.

Those themes would of course be the generational battle between the old hypocritical fuddy-duddies and their passionate, emotionally open offspring. It's honestly quite charming to watch Hammer try so hard to make a Gothic horror picture for those young people, those hippies, although given how far behind the curve Hammer was by the dawn of the '70s, it was probably still the Mods they had in mind when they were thinking of "youth culture". Which is as much to say, the attempt failed rather badly. Everything in Taste the Blood that has to do with young people falls powerfully flat, largely because of how unambiguously it's pandering to the audience.

On the other hand, everything involving the adults tends to work fairly well, although it's still without question the most peculiar story of the series to that point. Supporting Lee's oft-stated claim that the Hammer Dracula was becoming increasingly unlike the Stoker Dracula, this film's bloodsucker isn't even necessarily the villain of the piece; after all, his victims are abusive shitheels themselves, and it's hard not to let out a tiny cheer when he impels Alice to hit her drunken father in the face with a shovel. This is, to say the least, a novel approach for a vampire story, and one that's frankly refreshing. The A-story of Taste the Blood is very far from perfect - there is, for instance, the matter of killing Hargood first of the three adults, even though he is by then the primary character in the story - but it's a more than credible attempt to do something to revitalise what was by now an unabashedly old-fashioned genre.

In keeping with that desire to achieve something new, director Peter Sasdy, in his feature debut after several years in TV, shot Taste the Blood in a much more "realistic" style than any of the previous Dracula films had seen. The result is far less moody blacks and Gothic mystery than Terence Fisher or Freddie Francis had seen fit to bring to the table, and while part of me regrets the loss, a greater part of me is more than a little impressed by the way that Sasdy was able to do something completely different without completely violating the spirit of Hammer.

Despite all these good intentions, though, I can't help but think the film a failure. Partially it's because the central couple, Paul and Alice, are played by Anthony Higgins and Linda Hayden with such merciless boredom. Of course, it is the nature of these films that the lovers will be atrociously bland, and Higgins is a great deal better than Barry Andrews in Risen from the Grave, but I would still defy anyone watching this movie to come away with any real interest in the alleged protagonists. As always, it's Dracula who we're really here to see, and as always, Christopher Lee can do more in ten minutes than glassy-eyed youngsters can do in a whole movie. It's just never felt quite so damning as it does here, perhaps because the film's youth-in-revolution mentality deprives the count of a worthy adult antagonist.

And of course there are other problems: famously, the final scene is a colossal misfire that makes essentially no sense at all, and the story does much to stifle its nascent drama with endless scenes of people talking - another change that differentiates Taste the Blood from its predecessors, but not to its credit. It's a misfire, all in all; by far the smallest misfire in the series (the next few years would see some really spectacular crap branded with the Dracula name), but enough to make this the first time that a Hammer vampire film could honestly be considered "bad".

Reviews in this series

Dracula (Fisher, 1958)

The Brides of Dracula (Fisher, 1960)

Dracula: Prince of Darkness (Fisher, 1966)

Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (Francis, 1968)

Taste the Blood of Dracula (Sasdy, 1970)

Scars of Dracula (Baker, 1970)

Dracula A.D. 1972 (Gibson, 1972)

The Satanic Rites of Dracula (Gibson, 1974)

The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (Baker, 1974)

You wouldn't know that from the film's knock-out opening, though: in a coach traveling through the Carpathian woods, a boisterous British merchant named Weller (Roy Kinnear) is busy bragging to his unwilling companions about all the marvelous things he has acquired on his recent trip. Eventually, he mentions that he's on his way to Karlsberg (another place-name that hasn't, technically, appeared in any of the films yet), and just hearing the name of that town is enough to make one of his seatmates, suffering from a mental disorder of some kind, go into crazed spasms - and to throw Weller out of the coach.

Thus left without transportation, Weller burrows his way through the increasingly threatening woods, ultimately hearing a terrifying scream not that far from his own location. Going to check it out, what should he see but the final scene from Risen from the Grave, with Count Dracula pinned by a crucifix and writhing in agony as he bleeds out all over the ground. When the merchant finally works up the courage to go and check things out, the vampire's blood has turned into red powder, something that Weller finds much more fascinating than anything. Cue credits.

This is where the weird part kicks in. The story now jumps to London - the first time that any of Hammer's Dracula films have so much as referenced that city, where Bram Stoker's novel originally took place - where a bullying demagogue named William Hargood (Geoffrey Keen) is screaming at his daughter Alice (Linda Hayden) for her unspeakably wanton behavior at church that morning - flirting with a man, if you can believe such horrors. The young man in question, Paul Paxton (Anthony Higgins), seems nice enough, and Alice asks her mother (Gwen Watford) if there's some reason that Paul's father might have offended Hargood. Neither mother nor daughter has any explanation, but we get to find out very presently that the answer is quite different: under the excuse that it's time for his monthly charity trip to the East End, Hargood jumps into a cab where he meets none other than Samuel Paxton (Peter Sallis), and they're ultimately joined by a certain Jonathon Secker (John Carson). Their destination is in the East End, sure enough, but it's not charity work on their mind - it's a very private, high-class bordello. There they watch as a half naked woman cavorts with a snake, as beautiful girls without tops lounge on their arms (we get the first nipples in the series in this scene; and there's something inherently shocking about seeing nudity on that quintessentially '60s film stock, even now), and other tremendously low-key things that would have been unthinkably saucy in Victorian England.

The three men have enjoyed this routine for a while; long enough, anyay, to get bored with it. So they're more curious than angry when notorious rakehell Lord Courtley (Ralph Bates, in what was inteneded to have been his star-making role; see below) sweeps in and takes their women. Their curiosity leads them to invite the young lord out to dinner, where they approach him in an oh-so-circumspect way about introducing them to the kinkier pleasures, and he responds by taking them to Weller's store, where the merchant has for sale the cape and clasp of a certain Count Dracula, along with a box full of red powder. Courtley has apparently been eyeing this prize for some while, but never had enough money; but with three important gentlemen paying his way, he'll finally get his chance. After some dithering, the deal is made and Courtley takes the three men to his family crypt, decked out in the trappings of a black mass (somewhat unbelievably, this is all still the same evening). One elaborate ritual involving Courtley's blood later, all four men are holding goblets of the foaming, reconstituted blood of Dracula; the older gentlemen are reluctant to drink something so foul (it looks exactly like V-8, for the record), and it turns out that they're right: when Courtley downs his goblet, he starts spasming and falls to the ground, dead. The three men tear ass back to their homes where they order their wives and children to provide their alibis.

Now, here's a little story. Apparently Hammer wasn't initially interested in bringing Christopher Lee back as the count this time - the story was meant to use Dracula as an absent threat, sort of like Brides of Dracula, and Lord Courtley was to have been the main villain, in a sort of debutante's ball for Bates. But Warner Bros. stepped in and informed Hammer that if the Brits wanted American distribution, they'd damn well better have Dracula in their Dracula picture, leading studio head Anthony Hinds to quickly revise the back half of his screenplay. Meanwhile, Hammer was able to convince Chris Lee to come back to the role that he hated so very goddamn much for what was, by Hammer standards, a quite generous sum. This didn't keep Lee from bitching, of course, because if there's one thing he hated, it was playing Count Dracula. He hated it so much, that not only did he star in two Dracula films for Hammer in 1970, he also played the character in a Jesus Franco film titled Count Dracula. Basically, my point is that incriminating photos of Christopher Lee must be one of the things they give you when you join the horror filmmakers' union.

So, when Courtley turns into Dracula, as he must, the revived count waxes wroth at these three men who killed his disciple - despite the fact that Dracula never in his unlife ever laid eyes on Courtley. At any rate, it's enough of an offense for the vampire to declare vengeance upon the three gentlemen, and for the second film in a row, all I can do is sputter and ask: isn't revenge such a petty thing for the Lord of the Undead?

At least his scheme is fairly outré: enslave the men's children and force them to kill their fathers. True, it's not the same thing as having Dracula actually out doing the killing himself, and it reduces most of Lee's performance to standing in the shadows and counting down the number of men left to die (but you know what, nobody can stand and intone threatening lines quite like Christopher Lee). It's likely an artifact of the last-minute rewrite, bringing Dracula in unexpectedly; at any rate, it ties off the film's themes in a neat bow.

Those themes would of course be the generational battle between the old hypocritical fuddy-duddies and their passionate, emotionally open offspring. It's honestly quite charming to watch Hammer try so hard to make a Gothic horror picture for those young people, those hippies, although given how far behind the curve Hammer was by the dawn of the '70s, it was probably still the Mods they had in mind when they were thinking of "youth culture". Which is as much to say, the attempt failed rather badly. Everything in Taste the Blood that has to do with young people falls powerfully flat, largely because of how unambiguously it's pandering to the audience.

On the other hand, everything involving the adults tends to work fairly well, although it's still without question the most peculiar story of the series to that point. Supporting Lee's oft-stated claim that the Hammer Dracula was becoming increasingly unlike the Stoker Dracula, this film's bloodsucker isn't even necessarily the villain of the piece; after all, his victims are abusive shitheels themselves, and it's hard not to let out a tiny cheer when he impels Alice to hit her drunken father in the face with a shovel. This is, to say the least, a novel approach for a vampire story, and one that's frankly refreshing. The A-story of Taste the Blood is very far from perfect - there is, for instance, the matter of killing Hargood first of the three adults, even though he is by then the primary character in the story - but it's a more than credible attempt to do something to revitalise what was by now an unabashedly old-fashioned genre.

In keeping with that desire to achieve something new, director Peter Sasdy, in his feature debut after several years in TV, shot Taste the Blood in a much more "realistic" style than any of the previous Dracula films had seen. The result is far less moody blacks and Gothic mystery than Terence Fisher or Freddie Francis had seen fit to bring to the table, and while part of me regrets the loss, a greater part of me is more than a little impressed by the way that Sasdy was able to do something completely different without completely violating the spirit of Hammer.

Despite all these good intentions, though, I can't help but think the film a failure. Partially it's because the central couple, Paul and Alice, are played by Anthony Higgins and Linda Hayden with such merciless boredom. Of course, it is the nature of these films that the lovers will be atrociously bland, and Higgins is a great deal better than Barry Andrews in Risen from the Grave, but I would still defy anyone watching this movie to come away with any real interest in the alleged protagonists. As always, it's Dracula who we're really here to see, and as always, Christopher Lee can do more in ten minutes than glassy-eyed youngsters can do in a whole movie. It's just never felt quite so damning as it does here, perhaps because the film's youth-in-revolution mentality deprives the count of a worthy adult antagonist.

And of course there are other problems: famously, the final scene is a colossal misfire that makes essentially no sense at all, and the story does much to stifle its nascent drama with endless scenes of people talking - another change that differentiates Taste the Blood from its predecessors, but not to its credit. It's a misfire, all in all; by far the smallest misfire in the series (the next few years would see some really spectacular crap branded with the Dracula name), but enough to make this the first time that a Hammer vampire film could honestly be considered "bad".

Reviews in this series

Dracula (Fisher, 1958)

The Brides of Dracula (Fisher, 1960)

Dracula: Prince of Darkness (Fisher, 1966)

Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (Francis, 1968)

Taste the Blood of Dracula (Sasdy, 1970)

Scars of Dracula (Baker, 1970)

Dracula A.D. 1972 (Gibson, 1972)

The Satanic Rites of Dracula (Gibson, 1974)

The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (Baker, 1974)

Categories: british cinema, hammer films, horror, vampires, violence and gore