They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? 2008 Edition - #959

Settle in, dear reader, for one of the biggest and splashiest epics that Hollywood ever produced, the story of Judah Ben-Hur, prince of Judea, whose family and fortune were stolen away, who became a galley slave before rescuing a rich Roman and becoming a child of privilege in the wealthiest society in the world, who faced against his lifelong enemy in a bloody chariot race, and who finally learned the true meaning of Christmas.

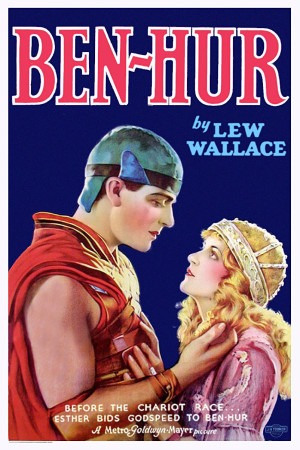

I'm not talking about William Wyler's 1959 Best Picture winner Ben-Hur, of course. My God, I hope we've all seen that movie already, and that nowadays any further commentary would be essentially redundant. No, the film I have in mind is 1925's Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, the second adaptation of Civil War general Lew Wallace's hugely successful doorstop from 1880. Though hyperbole and exaggeration are ever-present threats in any discussion of silent cinema, and numbers get tossed around with abandon, at least this much seems true: the '25 Ben-Hur was among the most expensive, possibly the most expensive film of the silent era, and one of the three or four most successful; though the legend further states that due to an almost inconceivable mess of start-and-stop productions, legal rights, and international payouts, MGM turned only a meager profit on their blockbuster. However, while I'm sure no-one wants to slight the studio's 83-year-old flirtation with bankruptcy, I expect that none of use are terribly interested in whether this executive or that got to keep his job, so much as seeing what $4-$6 million in 1925 dollars looks like onscreen. And the answer is that it looks pretty freaking good.

But before I get to that, the other thing that every viewer in the last 50 years has probably had first on her mind: how does the sort-of still well-known 1925 feature compare with the exceptionally famous 1959 classic? Frankly, I'm not the right person to answer that question, as I've always found Wyler's Ben-Hur to be bizarrely over-praised, and not all that good. Sure, the director had a fine eye for composition that nobody could take away, and of course there are the two big setpieces (the sea battle and chariot race) that are still beloved, but for my money, it all adds up to the longest three-and-a-half hours in cinema history, perhaps the dullest epic of any note ever produced. Basically, I'm easy to please: the 1925 film could hardly fail to better its illustrious successor. It does so for many small reasons, but there are two really huge ones: a) it is more than one hour shorter; b) it actually justifies the sub-title "A Tale of the Christ".

The 1959 film has Christ in it, sure, for about 8 minutes all told: a quick trip to the nativity, a cameo where he gives Charlton Heston's Judah Ben-Hur a ladle of water, and that's pretty much it until the crucifixion in the film's very last scene, an intrusion that fits into the film's narrative not at all and adds needless minutes to a film already screaming to have the padding ripped out. Whereas the earlier film opens with a recreation of Luke's nativity story that runs every bit of 12 minutes just by itself, and continues to drop in scenes of Christ's ministry throughout: that same water scene, plus greatest hits like the Sermon on the Mount, "he who is without sin" and Palm Sunday. Not to mention that in the '25 Ben-Hur, all of this makes some kind of narrative and thematic sense: the whole story is much more focused on the idea that the Romans are a tyrannic force crushing the lives of all Jews, the sufferings of Ben-Hur (Ramon Novarro) are a symptom of that tyranny as much as a story in and of themselves, and Christ is constantly foreshadowed as the King who will save the people from the might of corrupt Caesar. In essence, Ben-Hur and Jesus of Nazareth are the two faces of oppressed Jews: the one turns to anger and vengeance to assuage his suffering, the other transcends and thus gains the truer victory. If any of this is in the later film, I missed it entirely. Probably while making coffee to keep myself from passing out of boredom.

Ben-Hur came at a time when Hollywood was in a mad dash to make films bigger and bigger until they exploded from all the splashy excess: the huge Western epics The Covered Wagon and The Thief of Bagdad had just brought the gaudy excess of German fantasy into Hollywood's purview. It was time for the first of the great big literary adaptations, then, and that is exactly what Ben-Hur was: a film based first and foremost on the idea that the audience deserved the most amazing spectacle that MGM's coffers could provide. This had the result that it nearly always has in the eight decades since: a whole lot of sizzle, and a somewhat disappointing amount of steak. Not that Ben-Hur is an empty failure, not at all. But it's a film best enjoyed as a sample of the state of the art circa 1925, not as a timeless masterpiece. Frankly, most of the film's best tricks hardly register at all, given how many times we've seen them recreated (and improved upon) in the years since.

But let's say you can do that; put your mind in 1925, and Ben-Hur is quite the smashing entertainment indeed. The most obvious thing to modern eyes is undoubtedly the appearance of several scenes filmed in 2-strip Technicolor (by some five years the earliest color film footage I've ever seen, not counting tinted black-and-white), mostly limited to the Christ scenes, and the first scene set in Rome as Judah Ben-Hur is overwhelmed by the splendor of it all (splendor including topless women; oh, the Pre-Code days!). Even in 2008, the shift from monochrome to color, reedy though it is, is striking enough that you can tell that something really special just happened; if you saw The Dark Knight on IMAX, it's almost exactly the same feeling. There's an uncanniness in seeing unmistakable silent-film cinematography and acting done up in color (and an uncanniness in seeing topless women in a silent film at all), and this is probably the part of the film that holds up best with the littlest effort on the viewer's part.

Does it make much sense for the film as art? Well...frankly, just a little bit, and only if "art" is your codeword for "Christian propaganda" (fun fact: the film was marketed with the line, "The Picture Every Christian Ought To See!" That "ought" just kills me). Yes indeed, Christ was so special that he made black-and-white turn into grainy color. But that's even not really the point. The point is that in 1925, color film was hugely fucking cool, and that's very often the only justification that crowd-pleasers ever claim; for that matter, it's very often the only justification that they require. (Incidentally, the color makes it even clearer that the silent-era commonplace white people playing Middle Easterners - or a "Hindoo", in the opening scene - is tremendously unconvincing).

I'm a bit more impressed, though, by the parts that aren't so noticeable: for example, the chariot race, which was studied and copied in the 1959 film, but even so could hardly hope to seem fresh nowadays. I'd call it a draw, which film had the better race: the 1959 film is helped immeasurably by those shiny new 65mm cameras that captured it all, but the 1925 film is much more tightly edited, and has fewer obvious stuntmen. It's the editing that I'm really so taken by: the film as a whole doesn't advance the art much, but that one scene is among the very best-cut films of the whole silent era; it's one of the very few movies that honestly reminds me of the best chase scenes of the form's master, D.W. Griffith. The cuts in Ben-Hur's race as as violent and crashing as anything in the race itself, and the result is one of the most exhilarating and sophisticated thrills in any silent film, and to hell with the over-cranking that makes the whole movie jitter about.

The bigger setpiece, though, is the nearly 15-minute sea battle that ends the film's first hour. In Wyler's film, this was achieved (by accidental necessity) through blue-screens and models and a backlot; in the silent movie, there are actual boats, and they're actually slamming into each other, and actually being set on fire. It must have sucked to be a stuntman in the '20s. Anyway, the sea battle still legitimately holds up to the modern day because of that obvious full-scale physicality, and because of the unexpected violence that percolates throughout the sequence: a man is strapped to the prow of a pirate ship as it rams into a galley, the pirate chief hoists a sword with a headly neatly skewered on it, a man writhes as he's swung around on the business end of a spear. It's nasty stuff, the exact kind of thing that always gets nasty-minded kids (that is, all of them) all excited and still makes for smashing good action filmmaking.

Outside of what we would now call "popcorn entertainment" - and eye candy gigantic sets that recall Griffith's Intolerance and nothing else - Ben-Hur isn't really all that memorable. You almost certainly haven't heard of director Fred Niblo, and it's not without reason; though he deserves a great deal of credit for keeping the film on the rails, he's not a great visual artist. You probably haven't heard of the cast, either: Ramon Novarro as Ben-Hur, Francis X. Bushman as the sneering villain Messala (the only point that the 1959 film improves on the 1925 film is in the much deeper exploration of Messala's relationship with the hero), May McAvoy as the beautiful Esther, of the WASPy ringlets. None of them are bad, certainly - Novarro isn't afraid to mug as much as the hero of silent adventure films is always supposed to mug, and as a result he's light-years better than the excruciatingly stiff performance that Heston crapped out for the original - but none are particularly memorable; the only human being who really registers amidst all of the pomp is Iras (Carmel Myers), the Egyptian vamp who seduces Ben-Hur in a scene disappointingly excised from the later film. And she only really registers because, as we all know, vamps are always the best part of silent movies.

You know what? That's okay. This film lives and dies as spectacle, not as a deeply introspective movie; even its obvious religiosity is more spectacular than devout. And while I expect that John Q. Teenager would find a lot of hoke and slow pacing in the silent Ben-Hur the viewer willing to put some effort into won't walk away disappointed.

I'm not talking about William Wyler's 1959 Best Picture winner Ben-Hur, of course. My God, I hope we've all seen that movie already, and that nowadays any further commentary would be essentially redundant. No, the film I have in mind is 1925's Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, the second adaptation of Civil War general Lew Wallace's hugely successful doorstop from 1880. Though hyperbole and exaggeration are ever-present threats in any discussion of silent cinema, and numbers get tossed around with abandon, at least this much seems true: the '25 Ben-Hur was among the most expensive, possibly the most expensive film of the silent era, and one of the three or four most successful; though the legend further states that due to an almost inconceivable mess of start-and-stop productions, legal rights, and international payouts, MGM turned only a meager profit on their blockbuster. However, while I'm sure no-one wants to slight the studio's 83-year-old flirtation with bankruptcy, I expect that none of use are terribly interested in whether this executive or that got to keep his job, so much as seeing what $4-$6 million in 1925 dollars looks like onscreen. And the answer is that it looks pretty freaking good.

But before I get to that, the other thing that every viewer in the last 50 years has probably had first on her mind: how does the sort-of still well-known 1925 feature compare with the exceptionally famous 1959 classic? Frankly, I'm not the right person to answer that question, as I've always found Wyler's Ben-Hur to be bizarrely over-praised, and not all that good. Sure, the director had a fine eye for composition that nobody could take away, and of course there are the two big setpieces (the sea battle and chariot race) that are still beloved, but for my money, it all adds up to the longest three-and-a-half hours in cinema history, perhaps the dullest epic of any note ever produced. Basically, I'm easy to please: the 1925 film could hardly fail to better its illustrious successor. It does so for many small reasons, but there are two really huge ones: a) it is more than one hour shorter; b) it actually justifies the sub-title "A Tale of the Christ".

The 1959 film has Christ in it, sure, for about 8 minutes all told: a quick trip to the nativity, a cameo where he gives Charlton Heston's Judah Ben-Hur a ladle of water, and that's pretty much it until the crucifixion in the film's very last scene, an intrusion that fits into the film's narrative not at all and adds needless minutes to a film already screaming to have the padding ripped out. Whereas the earlier film opens with a recreation of Luke's nativity story that runs every bit of 12 minutes just by itself, and continues to drop in scenes of Christ's ministry throughout: that same water scene, plus greatest hits like the Sermon on the Mount, "he who is without sin" and Palm Sunday. Not to mention that in the '25 Ben-Hur, all of this makes some kind of narrative and thematic sense: the whole story is much more focused on the idea that the Romans are a tyrannic force crushing the lives of all Jews, the sufferings of Ben-Hur (Ramon Novarro) are a symptom of that tyranny as much as a story in and of themselves, and Christ is constantly foreshadowed as the King who will save the people from the might of corrupt Caesar. In essence, Ben-Hur and Jesus of Nazareth are the two faces of oppressed Jews: the one turns to anger and vengeance to assuage his suffering, the other transcends and thus gains the truer victory. If any of this is in the later film, I missed it entirely. Probably while making coffee to keep myself from passing out of boredom.

Ben-Hur came at a time when Hollywood was in a mad dash to make films bigger and bigger until they exploded from all the splashy excess: the huge Western epics The Covered Wagon and The Thief of Bagdad had just brought the gaudy excess of German fantasy into Hollywood's purview. It was time for the first of the great big literary adaptations, then, and that is exactly what Ben-Hur was: a film based first and foremost on the idea that the audience deserved the most amazing spectacle that MGM's coffers could provide. This had the result that it nearly always has in the eight decades since: a whole lot of sizzle, and a somewhat disappointing amount of steak. Not that Ben-Hur is an empty failure, not at all. But it's a film best enjoyed as a sample of the state of the art circa 1925, not as a timeless masterpiece. Frankly, most of the film's best tricks hardly register at all, given how many times we've seen them recreated (and improved upon) in the years since.

But let's say you can do that; put your mind in 1925, and Ben-Hur is quite the smashing entertainment indeed. The most obvious thing to modern eyes is undoubtedly the appearance of several scenes filmed in 2-strip Technicolor (by some five years the earliest color film footage I've ever seen, not counting tinted black-and-white), mostly limited to the Christ scenes, and the first scene set in Rome as Judah Ben-Hur is overwhelmed by the splendor of it all (splendor including topless women; oh, the Pre-Code days!). Even in 2008, the shift from monochrome to color, reedy though it is, is striking enough that you can tell that something really special just happened; if you saw The Dark Knight on IMAX, it's almost exactly the same feeling. There's an uncanniness in seeing unmistakable silent-film cinematography and acting done up in color (and an uncanniness in seeing topless women in a silent film at all), and this is probably the part of the film that holds up best with the littlest effort on the viewer's part.

Does it make much sense for the film as art? Well...frankly, just a little bit, and only if "art" is your codeword for "Christian propaganda" (fun fact: the film was marketed with the line, "The Picture Every Christian Ought To See!" That "ought" just kills me). Yes indeed, Christ was so special that he made black-and-white turn into grainy color. But that's even not really the point. The point is that in 1925, color film was hugely fucking cool, and that's very often the only justification that crowd-pleasers ever claim; for that matter, it's very often the only justification that they require. (Incidentally, the color makes it even clearer that the silent-era commonplace white people playing Middle Easterners - or a "Hindoo", in the opening scene - is tremendously unconvincing).

I'm a bit more impressed, though, by the parts that aren't so noticeable: for example, the chariot race, which was studied and copied in the 1959 film, but even so could hardly hope to seem fresh nowadays. I'd call it a draw, which film had the better race: the 1959 film is helped immeasurably by those shiny new 65mm cameras that captured it all, but the 1925 film is much more tightly edited, and has fewer obvious stuntmen. It's the editing that I'm really so taken by: the film as a whole doesn't advance the art much, but that one scene is among the very best-cut films of the whole silent era; it's one of the very few movies that honestly reminds me of the best chase scenes of the form's master, D.W. Griffith. The cuts in Ben-Hur's race as as violent and crashing as anything in the race itself, and the result is one of the most exhilarating and sophisticated thrills in any silent film, and to hell with the over-cranking that makes the whole movie jitter about.

The bigger setpiece, though, is the nearly 15-minute sea battle that ends the film's first hour. In Wyler's film, this was achieved (by accidental necessity) through blue-screens and models and a backlot; in the silent movie, there are actual boats, and they're actually slamming into each other, and actually being set on fire. It must have sucked to be a stuntman in the '20s. Anyway, the sea battle still legitimately holds up to the modern day because of that obvious full-scale physicality, and because of the unexpected violence that percolates throughout the sequence: a man is strapped to the prow of a pirate ship as it rams into a galley, the pirate chief hoists a sword with a headly neatly skewered on it, a man writhes as he's swung around on the business end of a spear. It's nasty stuff, the exact kind of thing that always gets nasty-minded kids (that is, all of them) all excited and still makes for smashing good action filmmaking.

Outside of what we would now call "popcorn entertainment" - and eye candy gigantic sets that recall Griffith's Intolerance and nothing else - Ben-Hur isn't really all that memorable. You almost certainly haven't heard of director Fred Niblo, and it's not without reason; though he deserves a great deal of credit for keeping the film on the rails, he's not a great visual artist. You probably haven't heard of the cast, either: Ramon Novarro as Ben-Hur, Francis X. Bushman as the sneering villain Messala (the only point that the 1959 film improves on the 1925 film is in the much deeper exploration of Messala's relationship with the hero), May McAvoy as the beautiful Esther, of the WASPy ringlets. None of them are bad, certainly - Novarro isn't afraid to mug as much as the hero of silent adventure films is always supposed to mug, and as a result he's light-years better than the excruciatingly stiff performance that Heston crapped out for the original - but none are particularly memorable; the only human being who really registers amidst all of the pomp is Iras (Carmel Myers), the Egyptian vamp who seduces Ben-Hur in a scene disappointingly excised from the later film. And she only really registers because, as we all know, vamps are always the best part of silent movies.

You know what? That's okay. This film lives and dies as spectacle, not as a deeply introspective movie; even its obvious religiosity is more spectacular than devout. And while I expect that John Q. Teenager would find a lot of hoke and slow pacing in the silent Ben-Hur the viewer willing to put some effort into won't walk away disappointed.