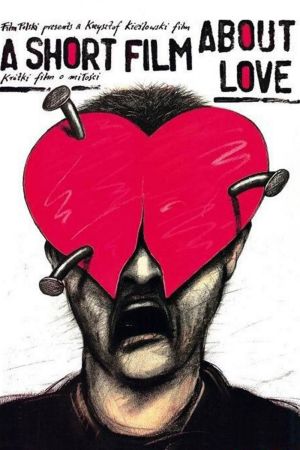

They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? 2008 Edition - #922

The second of two reviews. The first can be found here.

In 1988, Polish director Krzysztof Kieślowski and his co-writer Krzysztof Piesiewicz released Dekalog, a ten-episode TV miniseries explicating each of the Ten Commandments, that is acclaimed from virtually every corner as one of the essential masterpieces of world cinema. In the same year, the director produced two feature-length films adapted from two of the individual Dekalog episodes, telling expanded versions of the same stories, using alternate takes of the same material as well as footage shot expressly for the feature. The second of these, based on Dekalog: Six - "Thou Shalt Not Commit Adultery" - is A Short Film About Love.

How did I describe A Short Film About Killing? A "fundamentally different" experience from its progenitor Dekalog episode? That's completely accurate, but now I'm stuck looking for something more impressive than "fundamental". Because while ...Killing and Dekalog: Five are very different animals, they're basically making the same point using essentially the same story. Whereas ...Love and Dekalog: Six seem to be only incidentally similar, despite having narratives that proceed in the same path for something like 95% of the Dekalog episode. It's the five minutes before and after the episode that make the difference, though, and A Short Film About Love, by dint of having a brand-new final scene, turns out to be something entirely other than its Dekalog twin, no matter how much of the two films are identical.

19-year-old Tomek (Olaf Lubaszenko) lives in a Warsaw tenement with the mother (Stefania Iwinska) of his only good friend, currently serving with the UN in Serbia. He passes the time by spying on Magda (Grazyna Szapolowska), a promiscuous woman fifteen or twenty years his senior who lives across the courtyard. By the time we meet Tomek, his voyeurism has flowered into an obsession: he abuses his position at the local post office to send Magda bogus notices for certified mail, he gets a job delivering milk so he can be the first person she has contact with in the morning, and that's above and beyond the more normal stalker-type behavior like calling her up and not saying anything, and setting his alarm to make sure he remembers to watch for her every evening when she gets in at 8:30.

For her part, Magda initially has no use for the pathetic young romantic, whose efforts to cover his tracks fall apart rather quickly, and she humiliates him in the process of teaching him about her own, terrifically cynical definition of "love". Almost immediately afterwards, she realises that love and dispassionate fucking aren't necessarily the same thing at all, and she begins to considerably re-evaluate her opinion of the teenager who dared to think of her as more than a sex object.

As far as that goes, I could just as easily have been describing Dekalog: Six or the Short Film. Though, like the dyad of "Thou Shalt Not Kill" stories, there are enough differences to make the feature an unmistakably different creature; generally speaking, it doesn't linger quite as long and seems much brisker than its TV analogue. Several plot elements in Dekalog are fleshed out and contextualised a bit more fully in the film: Magda's game of solitaire that just sort of appears in the TV episode is used much more effectively as a metaphor for her self-imposed exile from humanity, and the personality of Tomek's absent friend Martin is deepened a great deal beyond "he's the guy who told me to watch you having sex all the time". It's a little bit less concerned with moral questions than a Dekalog episode would be, but it's not a Dekalog episode, so that's hardly a complaint. If I had to come up with one word to separate the film from the TV show, that word would be "richer": everything about the Short Film is fuller and more lived-in.

And then, the ending. I don't really want to give anything away, but I think I kind of have to, so spoiler-phobes are done with this essay now. The shorter version of the story ends with Magda asking Martin's mother if she can visit Tomek, now that he's back from the hospital (he slit his wrists in despair after Magda humiliated him). The older woman lets her inside. Short Film continues on to find Magda standing at Tomek's bedside in what we realise is the wider shot of the confusing image that opens the film. While the boy sleeps, she walks to his desk and looks through his telescope into her own apartment, where she sees a vision of herself, spilling milk and weeping (crying over spilled milk is an important motif in both versions of the story; moreover, at one point in Dekalog a bottle is spilled, where it is not in the Short Film; I leave as an exercise for the attentive viewer to figure out where this is and what it may mean). Tomek comes in and comforts her, and back at the telescope, Magda smiles.

It's insulting to Kieślowski to sum this up as "she's having a vision of what a life with love would be like", but not therefore inaccurate, just needlessly reductive. At any rate, what's really interesting, at least to me, isn't what the ending means (what does "means" mean in a Kieślowski film, anyhow?), but what it does to the story: all of a sudden, Short Film becomes a magical realist movie, and a bit of a mindfucker, far more than the vague hints of magical realism scattered throughout Dekalog. This ending is from the director of Blind Chance and Three Colors: Red, and not as much from the director of Camera Buff and Three Colors: White. And certainly, it's not from the director of Deklaog, which is certainly a spiritual piece, but one grounded in the earthbound realities of Warsaw in the final moments of Polish Communism. At any rate, I cannot recall one moment in any of the ten films equal to "she watches herself through a telescope".

I mean neither to praise nor condemn A Short Film About Love, merely to point out how unabashedly different it is from its theoretical source. Personally, I find it to be far more compelling and beautiful than the Dekalog episode which shares its story, though I should confess that the sixth film is quite a long way from being my favorite of the ten, if I were to get into the vulgar act of ranking them. It's much simpler, aesthetically, than ...Killing, or any of the knock-out masterpieces that the director would produce in the following decade, but its story is unnervingly powerful anyway, and that makes up for a lot; ...Love is an especially pure example of Kieślowski's sometimes-hidden Romantic side, and humane and touching in all the ways that ...Killing is unpleasant and devastating.

In 1988, Polish director Krzysztof Kieślowski and his co-writer Krzysztof Piesiewicz released Dekalog, a ten-episode TV miniseries explicating each of the Ten Commandments, that is acclaimed from virtually every corner as one of the essential masterpieces of world cinema. In the same year, the director produced two feature-length films adapted from two of the individual Dekalog episodes, telling expanded versions of the same stories, using alternate takes of the same material as well as footage shot expressly for the feature. The second of these, based on Dekalog: Six - "Thou Shalt Not Commit Adultery" - is A Short Film About Love.

How did I describe A Short Film About Killing? A "fundamentally different" experience from its progenitor Dekalog episode? That's completely accurate, but now I'm stuck looking for something more impressive than "fundamental". Because while ...Killing and Dekalog: Five are very different animals, they're basically making the same point using essentially the same story. Whereas ...Love and Dekalog: Six seem to be only incidentally similar, despite having narratives that proceed in the same path for something like 95% of the Dekalog episode. It's the five minutes before and after the episode that make the difference, though, and A Short Film About Love, by dint of having a brand-new final scene, turns out to be something entirely other than its Dekalog twin, no matter how much of the two films are identical.

19-year-old Tomek (Olaf Lubaszenko) lives in a Warsaw tenement with the mother (Stefania Iwinska) of his only good friend, currently serving with the UN in Serbia. He passes the time by spying on Magda (Grazyna Szapolowska), a promiscuous woman fifteen or twenty years his senior who lives across the courtyard. By the time we meet Tomek, his voyeurism has flowered into an obsession: he abuses his position at the local post office to send Magda bogus notices for certified mail, he gets a job delivering milk so he can be the first person she has contact with in the morning, and that's above and beyond the more normal stalker-type behavior like calling her up and not saying anything, and setting his alarm to make sure he remembers to watch for her every evening when she gets in at 8:30.

For her part, Magda initially has no use for the pathetic young romantic, whose efforts to cover his tracks fall apart rather quickly, and she humiliates him in the process of teaching him about her own, terrifically cynical definition of "love". Almost immediately afterwards, she realises that love and dispassionate fucking aren't necessarily the same thing at all, and she begins to considerably re-evaluate her opinion of the teenager who dared to think of her as more than a sex object.

As far as that goes, I could just as easily have been describing Dekalog: Six or the Short Film. Though, like the dyad of "Thou Shalt Not Kill" stories, there are enough differences to make the feature an unmistakably different creature; generally speaking, it doesn't linger quite as long and seems much brisker than its TV analogue. Several plot elements in Dekalog are fleshed out and contextualised a bit more fully in the film: Magda's game of solitaire that just sort of appears in the TV episode is used much more effectively as a metaphor for her self-imposed exile from humanity, and the personality of Tomek's absent friend Martin is deepened a great deal beyond "he's the guy who told me to watch you having sex all the time". It's a little bit less concerned with moral questions than a Dekalog episode would be, but it's not a Dekalog episode, so that's hardly a complaint. If I had to come up with one word to separate the film from the TV show, that word would be "richer": everything about the Short Film is fuller and more lived-in.

And then, the ending. I don't really want to give anything away, but I think I kind of have to, so spoiler-phobes are done with this essay now. The shorter version of the story ends with Magda asking Martin's mother if she can visit Tomek, now that he's back from the hospital (he slit his wrists in despair after Magda humiliated him). The older woman lets her inside. Short Film continues on to find Magda standing at Tomek's bedside in what we realise is the wider shot of the confusing image that opens the film. While the boy sleeps, she walks to his desk and looks through his telescope into her own apartment, where she sees a vision of herself, spilling milk and weeping (crying over spilled milk is an important motif in both versions of the story; moreover, at one point in Dekalog a bottle is spilled, where it is not in the Short Film; I leave as an exercise for the attentive viewer to figure out where this is and what it may mean). Tomek comes in and comforts her, and back at the telescope, Magda smiles.

It's insulting to Kieślowski to sum this up as "she's having a vision of what a life with love would be like", but not therefore inaccurate, just needlessly reductive. At any rate, what's really interesting, at least to me, isn't what the ending means (what does "means" mean in a Kieślowski film, anyhow?), but what it does to the story: all of a sudden, Short Film becomes a magical realist movie, and a bit of a mindfucker, far more than the vague hints of magical realism scattered throughout Dekalog. This ending is from the director of Blind Chance and Three Colors: Red, and not as much from the director of Camera Buff and Three Colors: White. And certainly, it's not from the director of Deklaog, which is certainly a spiritual piece, but one grounded in the earthbound realities of Warsaw in the final moments of Polish Communism. At any rate, I cannot recall one moment in any of the ten films equal to "she watches herself through a telescope".

I mean neither to praise nor condemn A Short Film About Love, merely to point out how unabashedly different it is from its theoretical source. Personally, I find it to be far more compelling and beautiful than the Dekalog episode which shares its story, though I should confess that the sixth film is quite a long way from being my favorite of the ten, if I were to get into the vulgar act of ranking them. It's much simpler, aesthetically, than ...Killing, or any of the knock-out masterpieces that the director would produce in the following decade, but its story is unnervingly powerful anyway, and that makes up for a lot; ...Love is an especially pure example of Kieślowski's sometimes-hidden Romantic side, and humane and touching in all the ways that ...Killing is unpleasant and devastating.