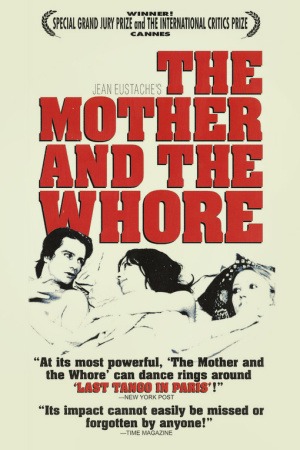

They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? 2008 Edition - #156

As much as anybody can be, Jean-Pierre Léaud is the face of the French New Wave, and thus it is well that he so dominates Jean Eustache's 1973 masterpiece The Mother and the Whore, a three and a half hour monolith that stands Janus-faced as both the last film of that movement and perhaps the first film to consider the meaning of the New Wave after its conclusion: he is in literally every scene, and he's in a significant majority of the film's shots.* He plays Alexandre, a character who blends all of the significant elements of a New Wave hero: he is passionately enthusiastic about left wing politics but far too self-absorbed to do anything about that, his understanding of human behavior is almost completely informed by pop culture and especially movies, he is incredibly overeducated, he thinks of sex constantly but as an object and not an act, he disdains work in favor of living as a sort of free-form performance piece. As the movie presents him, he is almost totally devoid of redeeming characteristics, but never at any moment do we hate him even though we are constantly aware that he is basically an awful person.

He is at the center of an epic study of a situation that exists almost without any sort of plot at all: after being rebuffed by Gilberte (Isabelle Weingarten), a college student he claims is the love of his life, Alexandre picks increasingly petty fights with his girlfriend Marie (Bernadette Lafont), whose apartment he calls home, and who provide seemingly all of his financial support, while starting up an affair with the pretty nurse Veronika (Françoise Lebrun). Marie and Veronika know about each other; indeed, Alexandre takes no small pleasure in watching the women squirm as he lords his apparent mastery of their triangle over them. But eventually, things start to break down a bit, Veronika moves in with the other two, and what follows is not exactly a love triangle and not at all a ménage à trois, but some kind of strange arrangement that there isn't a word for yet.

It might seem like there's a lot of time spent on a fairly concise drama, but The Mother and the Whore isn't concerned with the conflicts present in its plot; it could have resolved those just fine in a third of the time. Instead, the focus is on the shifting power dynamic between three people who all have an unhidden desire to watch the other two in pain, and the film's vast running time allows Eustache to present those shifts so gradually as to be almost undetectable; that is, we are aware that the third hour and the first hour are very different, but at each step it's not entirely certain how that change happened. It comes close to capturing the pacing of life itself, where great changes happen at great length.

As such, the film's themes are those of life, and far be it from me to sit here and dryly repeat what any viewer of the film is going to pick up. What's most obvious is how the film presents its central trio: though the protagonist is the callow, obnoxious Alexandre, who likes to hear himself talk and launches regularly into marathon-lengthy monologues about indecipherable subjects, the focus, as the title suggests, is on the women, Marie the mother and Veronika the whore, although a great part of Eustache's work is to demolish the framework of that dichotomy. This is not a film about Womanhood, it is a film in which two specific women are presented in great detail, and their actions and words do not slot them into any social narrative, even though Veronika clearly thinks of herself that way. As much as anything, The Mother and the Whore is a treatise on how slippery defining a person with any number of labels can be. It's not that any of the three seem like people who could exist outside of this movie - they are unmistakable written characters, especially Alexandre - but they are rarely the people that they think they are, or that we expect them to be.

Shot in the Academy aspect ratio of 1.37:1 on 16mm film, Eustache uses a huge number of long takes that consist mostly of stylised close-ups, often panning from one close-up to another. We spend as much time watching people listening as we do watching people talking or acting; like Ingmar Bergman's Scenes from a Marriage in the same year, this is overwhelmingly a film about faces and what they can tell us about the the thoughts of their owners. When it's done right, a combination of great photography, writing and acting, I believe this to be the most transcended form of cinema, and in The Mother and the Whore it has been done virtually as well as I have ever seen it: especially in the especially Bergmanesque sequence near the end, when Veronika delivers a magnificent speech for what seems like an eternity, expressing her frustration at living in a society that dictates roles and meanings to undirected behavior. The camera never wavers from her face as she speaks in tones from conversational to angry to tearful to clinical, and it is thrilling.

It's hard to say whether the film is "about" the women or about how Alexandre thinks of them; my inclination is towards the latter, simply because of Léaud's massive role and the degree to which the film feels like a commentary on the phallocentric cinema of Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, the two directors most responsible for the actor's persona. Certainly Alexandre is the character who we get the strongest grasp on during the film: although he, like the women, seems to change the more we look at him, his basic nature is never in doubt. He's a naval-gazing user, with only the exact nature of that naval-gazing shifting as the film progresses. Moreover, he is the source of the film's comically corrosive tone. It's hard to feel much sympathy or affection for anybody in the movie, and that has a lot to do with how closely the film is aligned to Alexandre's point of view.

Of all the movies I have seen that address the topic of the social malaise of disaffected thirty-year-olds, The Mother and the Whore is certainly the most pessimistic, and probably not the most honest; but it has the weight of truth to it. Ultimately, Alexandre, Marie and Veronika are nothing more than people who aren't sure whether the lives they're living are the lives they're stuck with, or the lives they want, and each of them deals with this in a private way: Alexandre is superior and controlling, Marie is detached and ironic, Veronika gives in before protesting. It is a movie about static life, given the scope of an epic. That ought to be a paradox, and yet it possesses gravity and humor enough that it really does feel like the film contains the whole world.

He is at the center of an epic study of a situation that exists almost without any sort of plot at all: after being rebuffed by Gilberte (Isabelle Weingarten), a college student he claims is the love of his life, Alexandre picks increasingly petty fights with his girlfriend Marie (Bernadette Lafont), whose apartment he calls home, and who provide seemingly all of his financial support, while starting up an affair with the pretty nurse Veronika (Françoise Lebrun). Marie and Veronika know about each other; indeed, Alexandre takes no small pleasure in watching the women squirm as he lords his apparent mastery of their triangle over them. But eventually, things start to break down a bit, Veronika moves in with the other two, and what follows is not exactly a love triangle and not at all a ménage à trois, but some kind of strange arrangement that there isn't a word for yet.

It might seem like there's a lot of time spent on a fairly concise drama, but The Mother and the Whore isn't concerned with the conflicts present in its plot; it could have resolved those just fine in a third of the time. Instead, the focus is on the shifting power dynamic between three people who all have an unhidden desire to watch the other two in pain, and the film's vast running time allows Eustache to present those shifts so gradually as to be almost undetectable; that is, we are aware that the third hour and the first hour are very different, but at each step it's not entirely certain how that change happened. It comes close to capturing the pacing of life itself, where great changes happen at great length.

As such, the film's themes are those of life, and far be it from me to sit here and dryly repeat what any viewer of the film is going to pick up. What's most obvious is how the film presents its central trio: though the protagonist is the callow, obnoxious Alexandre, who likes to hear himself talk and launches regularly into marathon-lengthy monologues about indecipherable subjects, the focus, as the title suggests, is on the women, Marie the mother and Veronika the whore, although a great part of Eustache's work is to demolish the framework of that dichotomy. This is not a film about Womanhood, it is a film in which two specific women are presented in great detail, and their actions and words do not slot them into any social narrative, even though Veronika clearly thinks of herself that way. As much as anything, The Mother and the Whore is a treatise on how slippery defining a person with any number of labels can be. It's not that any of the three seem like people who could exist outside of this movie - they are unmistakable written characters, especially Alexandre - but they are rarely the people that they think they are, or that we expect them to be.

Shot in the Academy aspect ratio of 1.37:1 on 16mm film, Eustache uses a huge number of long takes that consist mostly of stylised close-ups, often panning from one close-up to another. We spend as much time watching people listening as we do watching people talking or acting; like Ingmar Bergman's Scenes from a Marriage in the same year, this is overwhelmingly a film about faces and what they can tell us about the the thoughts of their owners. When it's done right, a combination of great photography, writing and acting, I believe this to be the most transcended form of cinema, and in The Mother and the Whore it has been done virtually as well as I have ever seen it: especially in the especially Bergmanesque sequence near the end, when Veronika delivers a magnificent speech for what seems like an eternity, expressing her frustration at living in a society that dictates roles and meanings to undirected behavior. The camera never wavers from her face as she speaks in tones from conversational to angry to tearful to clinical, and it is thrilling.

It's hard to say whether the film is "about" the women or about how Alexandre thinks of them; my inclination is towards the latter, simply because of Léaud's massive role and the degree to which the film feels like a commentary on the phallocentric cinema of Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, the two directors most responsible for the actor's persona. Certainly Alexandre is the character who we get the strongest grasp on during the film: although he, like the women, seems to change the more we look at him, his basic nature is never in doubt. He's a naval-gazing user, with only the exact nature of that naval-gazing shifting as the film progresses. Moreover, he is the source of the film's comically corrosive tone. It's hard to feel much sympathy or affection for anybody in the movie, and that has a lot to do with how closely the film is aligned to Alexandre's point of view.

Of all the movies I have seen that address the topic of the social malaise of disaffected thirty-year-olds, The Mother and the Whore is certainly the most pessimistic, and probably not the most honest; but it has the weight of truth to it. Ultimately, Alexandre, Marie and Veronika are nothing more than people who aren't sure whether the lives they're living are the lives they're stuck with, or the lives they want, and each of them deals with this in a private way: Alexandre is superior and controlling, Marie is detached and ironic, Veronika gives in before protesting. It is a movie about static life, given the scope of an epic. That ought to be a paradox, and yet it possesses gravity and humor enough that it really does feel like the film contains the whole world.