They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? 2008 Edition - #352

It is sometimes the case that a movie opens with a moment so perfect that you just know that no matter what happens, it is going to own you body and soul. Such is the case with Georges Franju's extraordinarily influential horror film Eyes Without a Face, which opens with a musical theme that sounds both boisterous and threatening, a calliope played in a discordant harmony like the frenzied music of Hell's own carousel; and while this most excellent piece of horror music is assaulting our ears, the camera tracks swiftly down the road at night, showing nothing but the black, black sky and the white, white skeletons of bare trees standing stark against that blackness, as the credits roll. It is a phenomenal piece of mood setting, and one of the very finest blends of image and music in the genre, equaled only in The Exorcist and Halloween.

The opening scene of the film proper ain't too shabby, either; as that crazy music plays on (composed, by the way, by Maurice Jarre, of Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago; his work in this film is every bit as good as those two iconic scores), the tracking shots give way to a car speeding down those very same tree-lined streets, driven by a mysterious woman whose demeanor just oozes Up To No Good (she is played by Alida Valli, one of the greatest of those enigmatic European actresses so popular in the decades after World War II). After a few moments, it's clear that somebody is in the back seat behind her; after a few moments more, it's clear that this somebody isn't exactly alive anymore, and that there's something - we can't tell what - not at all right with this somebody's face. And a few moments later it doesn't matter what we notice, after the woman takes the body out of the back seat and drops it into the Seine.

That is one hell of an opening, familiar maybe but never done quite so well, with such poetically surreal foreboding. It's that poetry that goes some way to explain why Eyes Without a Face is famously a horror movie that people who loathe the horror genre still regard as a cinematic masterpiece, and people who adore the genre regard as one of its highest points. These are not distinctions that matter over-much in our current climate, which seeks to obliterate the distinction between high and low art forms, but back in 1960 that wasn't the case at all, and the uncanny haze that snakes through the film's visuals and even its narrative made it "okay" for serious people to regard Franju as a genius of mood-setting. The French Surrealists and Poetic Realists, and the German Expressionists all influence the project, even as the gore-hounds at Britain's Hammer Studios can probably be regarded as the director's chief inspiration.

The curious thing about the film is that its heralded style was at least in part Franju's gambit to solve a seemingly intractable problem: how to tell a story steeped in violence and lurid exploitation when his producers were breathing down his neck to make a movie that could pass the British, French and Italian censor boards uncut (he succeeded: the only country to cut the film during its initial release was, surprisingly, the United States). That's why we see only hints of things - what happened to that dead woman's face? - and why horror is carried out almost entirely through the ghostly mise en scène, instead of through monsters and madmen. No small feat for a film that hinges on a crazy doctor's quest to restore his daughter's disfigured face through butchering several innocent virginal youths.

The mad scientist in question is Dr. Génessier (Pierre Brasseur), not the much more sensational Dr. Faustus promised by the original US release title (The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus, if you must know). Some time back, the widowed doctor was responsible for a car accident that left his daughter Christiane's (Edith Scob) face in tatters, and this pushed him to a breaking point; having lost one woman in his life, he could not bear to lose the other, and so he turned his research into the science of organ transplants to a very dark extreme. If I might go as far from visually evocative French cinema as you can go, this is almost exactly the same scenario that opens The Brain That Wouldn't Die, one of the most famously awful American films ever made, produced right around the same time. I'm not sure why I bring this up, unless it's to point out why things like tone and style matter so very, very much.

The plot of Eyes Without a Face is paint-by-numbers; even if you've never seen a mad scientist flick you can probably guess the rough sequence of finding victims and dodging cops that follows. And being that horror films of every age are meant to shock their audience, you'd be unsurprised to learn that yes, the film includes a surgery scene that's supposed to just knock us flat on our asses. You'd be surprised as anything to learn that this scene holds up, being much less sensational than so many of the truly gory features from the same era, and subscribing to the same "must not show the audience too much" mentality that runs though every frame of the movie.

Why, by the way, is it always an accident of budget, or censorship, or technical limitations that lead filmmakers to hide as much of their horrors as possible from the audience? It usually works exceedingly well, yet nobody ever seems to set it as their goal.

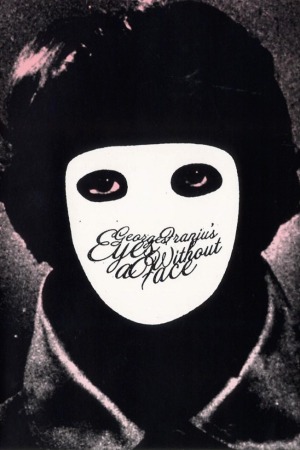

By far, though, the aspect of the film that is most horrifying is not its concept, nor its "gore" scenes, nor even its off-kilter music, but the young woman at its center. Many characters are more present onscreen than Christiane, but none of them have a tenth of her impact. Wandering around in a mask designed to protect and hide her scars, revealing only her sad, judgmental eyes, Christiane is played by Scob within an inch of perfection, and she looks as terrifying as any monster in cinema history. We can tell the mask is supposed to be white, but thanks to the miracle of black-and-white stock, it seems almost the exact same hue as her skin, and the subsequent effect of watching a normal young woman with a frozen face is as uncanny as anything. Later in the film, when she moves the mask's mouth to talk, this feeling rises, and in the brief time that she has a successful face transplant, before the skin starts to rot away, and the face we've seen still and unmoving for so long becomes soft and flexible, it's quite literally the most unexpectedly creepy thing I've ever seen in a movie. Coupled with Scob's undeniable beauty, Christiane comes across as equal parts movie monster and mysterious fairy-tale princess. She is an iconic figure as much as any character in any movie has ever been.

I've spent the past few hours trying to come up with a single bad thing to say about Eyes Without a Face, and I cannot do it. It looks like nothing else out there, and it's one of the most unusual horror films I know of for that reason, and for the fact that it plays by almost none of the usual thematic rules of its genre (Génassier isn't a sociopath, Christiane is neither a monster nor a put-upon saint, and we don't get any of the expected moral pronouncement from the film's highly predictable denouement). It is both a horror movie and a dreamy art film without peer, and dare I say, one of the high water marks of French cinema.

The opening scene of the film proper ain't too shabby, either; as that crazy music plays on (composed, by the way, by Maurice Jarre, of Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago; his work in this film is every bit as good as those two iconic scores), the tracking shots give way to a car speeding down those very same tree-lined streets, driven by a mysterious woman whose demeanor just oozes Up To No Good (she is played by Alida Valli, one of the greatest of those enigmatic European actresses so popular in the decades after World War II). After a few moments, it's clear that somebody is in the back seat behind her; after a few moments more, it's clear that this somebody isn't exactly alive anymore, and that there's something - we can't tell what - not at all right with this somebody's face. And a few moments later it doesn't matter what we notice, after the woman takes the body out of the back seat and drops it into the Seine.

That is one hell of an opening, familiar maybe but never done quite so well, with such poetically surreal foreboding. It's that poetry that goes some way to explain why Eyes Without a Face is famously a horror movie that people who loathe the horror genre still regard as a cinematic masterpiece, and people who adore the genre regard as one of its highest points. These are not distinctions that matter over-much in our current climate, which seeks to obliterate the distinction between high and low art forms, but back in 1960 that wasn't the case at all, and the uncanny haze that snakes through the film's visuals and even its narrative made it "okay" for serious people to regard Franju as a genius of mood-setting. The French Surrealists and Poetic Realists, and the German Expressionists all influence the project, even as the gore-hounds at Britain's Hammer Studios can probably be regarded as the director's chief inspiration.

The curious thing about the film is that its heralded style was at least in part Franju's gambit to solve a seemingly intractable problem: how to tell a story steeped in violence and lurid exploitation when his producers were breathing down his neck to make a movie that could pass the British, French and Italian censor boards uncut (he succeeded: the only country to cut the film during its initial release was, surprisingly, the United States). That's why we see only hints of things - what happened to that dead woman's face? - and why horror is carried out almost entirely through the ghostly mise en scène, instead of through monsters and madmen. No small feat for a film that hinges on a crazy doctor's quest to restore his daughter's disfigured face through butchering several innocent virginal youths.

The mad scientist in question is Dr. Génessier (Pierre Brasseur), not the much more sensational Dr. Faustus promised by the original US release title (The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus, if you must know). Some time back, the widowed doctor was responsible for a car accident that left his daughter Christiane's (Edith Scob) face in tatters, and this pushed him to a breaking point; having lost one woman in his life, he could not bear to lose the other, and so he turned his research into the science of organ transplants to a very dark extreme. If I might go as far from visually evocative French cinema as you can go, this is almost exactly the same scenario that opens The Brain That Wouldn't Die, one of the most famously awful American films ever made, produced right around the same time. I'm not sure why I bring this up, unless it's to point out why things like tone and style matter so very, very much.

The plot of Eyes Without a Face is paint-by-numbers; even if you've never seen a mad scientist flick you can probably guess the rough sequence of finding victims and dodging cops that follows. And being that horror films of every age are meant to shock their audience, you'd be unsurprised to learn that yes, the film includes a surgery scene that's supposed to just knock us flat on our asses. You'd be surprised as anything to learn that this scene holds up, being much less sensational than so many of the truly gory features from the same era, and subscribing to the same "must not show the audience too much" mentality that runs though every frame of the movie.

Why, by the way, is it always an accident of budget, or censorship, or technical limitations that lead filmmakers to hide as much of their horrors as possible from the audience? It usually works exceedingly well, yet nobody ever seems to set it as their goal.

By far, though, the aspect of the film that is most horrifying is not its concept, nor its "gore" scenes, nor even its off-kilter music, but the young woman at its center. Many characters are more present onscreen than Christiane, but none of them have a tenth of her impact. Wandering around in a mask designed to protect and hide her scars, revealing only her sad, judgmental eyes, Christiane is played by Scob within an inch of perfection, and she looks as terrifying as any monster in cinema history. We can tell the mask is supposed to be white, but thanks to the miracle of black-and-white stock, it seems almost the exact same hue as her skin, and the subsequent effect of watching a normal young woman with a frozen face is as uncanny as anything. Later in the film, when she moves the mask's mouth to talk, this feeling rises, and in the brief time that she has a successful face transplant, before the skin starts to rot away, and the face we've seen still and unmoving for so long becomes soft and flexible, it's quite literally the most unexpectedly creepy thing I've ever seen in a movie. Coupled with Scob's undeniable beauty, Christiane comes across as equal parts movie monster and mysterious fairy-tale princess. She is an iconic figure as much as any character in any movie has ever been.

I've spent the past few hours trying to come up with a single bad thing to say about Eyes Without a Face, and I cannot do it. It looks like nothing else out there, and it's one of the most unusual horror films I know of for that reason, and for the fact that it plays by almost none of the usual thematic rules of its genre (Génassier isn't a sociopath, Christiane is neither a monster nor a put-upon saint, and we don't get any of the expected moral pronouncement from the film's highly predictable denouement). It is both a horror movie and a dreamy art film without peer, and dare I say, one of the high water marks of French cinema.