They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? 2008 Edition - #727

Tobacco Road is a bizarre, schizophrenic little bit of a movie. Coming at a place in John Ford's canon right after The Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home, and right before How Green Was My Valley and his war-related hiatus from studio filmmaking, Tobacco Road would seem to fit comfortably in that line of titles - a look at the indignities suffered by an old farmer at the end of the Depression, it almost comes across like a distaff sequel to Grapes - except for the strange matter of its comedy. In all of Ford's career, his use of ethnic caricature was one of the hallmarks of his style: sometimes working well to add texture and personality to his sprawling casts, sometimes coming across as insulting farce. But never in any of his films have I been so taken aback as by the raw mockery present in Tobacco Road, which treats an impoverished Georgian family with all the delicacy of a pack of baboons.

And yet, this shrill hicksploitation, packed with lowest kind of humor outside of fart jokes, is graced with some of the loveliest and most thematically evocative imagery in the director's career, courtesy of three-time Oscar winning cinematographer Arthur Miller. That's not an easy claim to make of a filmmaker known for such rich visuals as Ford, and thus is the film's split personality: hacky, low-rent comedy mashed-up against sublime black-and-white cinematography that gives the barbaric content poetic resonance that it frankly doesn't deserve.

The script, such as it is, took a long and winding road to end up in America's cinemas in 1941: first, in 1932 the left-wing author Erskine Caldwell wrote a novel, a serious study of the literally penniless Lester family, sharecroppers driven to desperation as the worst years of the Great Depression bankrupted the owner of the family's land and left them unable to farm cotton as they had done for generations. The Lesters' behavior is selfish and sinful, but they are unable to do anything else, without the slightest hope of money in the future. The sober and unhappy book was adapted a year later by Jack Kirkland for the Broadway stage, where it ran for a record-setting 3182 consecutive performances over eight years.

Near the end of the play's run, Darryl Zanuck of 20th Century Fox commissioned a screenplay based on the stage version by Nunnally Johnson, fresh of off the much-heralded film adaptation of Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath, with the expectation that John Ford would direct (the third and final collaboration between the writer and director). Johnson and Ford elected to scrap the serious social criticism in the novel and play (perhaps fearing a retread of their most recent project?), and the new story, though superficially similar to its source material, is much lighter, offering fewer moments of moral introspection and more scenes of the Lesters screaming at each other.

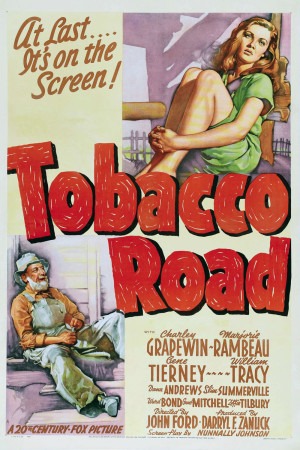

The main arc of the film concerns Jeeter Lester (Charley Grapewin) and his wife Ada (Elizabeth Patterson), and their efforts to raise enough money to save their cotton farm for just one more season. Complicating life are the local religious busybody, Bessie Rice (Marjorie Rambeau), abusive son-in-law Lov Bensey (Ford's stock company stalwart Ward Bond), and the two Lester children still living at home, sex-starved 23-year-old Ellie Mae (Gene Tierney) and loud-mouthed, emotionally stunted 20-year-old Dude (William Tracy).

It's probably fair to say that what I dislike about the film isn't "the script" so much as it is "Dude." Somewhere along the line - whether in Johnson's screenplay, Ford's direction, or perhaps just something that Tracy brought to the character - Dude Lester manifested himself as a force of pure evil, hollering every single line and making obnoxious honking noises to show how much he loves cars. This is at least somewhat motivated, with the clearly unloving Jeeter treating his son like an animal and his son responding in kind as a howler monkey, but so unwatchable is the net result (and remember, this is supposed to be funny) that it would have been smarter to throw the whole edifice out and start fresh.

Dude is a microcosm for all that is wrong with the film: flat characters that are a cartoon of Southern ignorance more offensive and misguided than the most secluded ivory tower elitist should have been able to imagine. Just months after completing The Grapes of Wrath, I cannot fathom how John Ford found it in himself to attach his name to this project, as good as taking the noble and flawed and thoroughly realistic Joads and cramming them into a sub-par episode of Hee Haw. It bears repeating that dialect comedy was a longstanding element of Ford's art - it existed in his films at least as early as 1924's The Iron Horse, and that was even a silent movie - and it was often an uncomfortable element, sometimes loving and sometimes mocking, sometimes both within the same scene. But nothing I had ever seen by Ford prepared me for Tobacco Road and it's parade of the ugliest stereotypes about human behavior. There is quite literally nothing in the story worth saving - awful people behaving awfully and it's not even the tiniest bit amusing.

Then, there's the film's imagery, which is not merely worth saving, but apparently good enough to propel the film to the top 1000 films of all time, by at least one yardstick. Perhaps that's as it should be - cinema is visual, and Tobacco Road is a visual masterpiece for virtually every shot of its 84 minutes. On the simplest level, it's a pretty movie, full of frames you just want to grab and put on the wall, but it goes deeper than that. The leaf-dappled light on every surface is lovely to look at, but it's also a reflection how the characters are marked by the land, and it suggests that the land keeps the Lesters in perpetual half-light, the full sun being blocked by the natural world which once gave the family its livelihood.

As the story progresses, and Jeeter becomes more and more desperate in his attempts to beg, borrow or steal $100, the film grows progressively darker, culminating in a fifteen-minute sequence near the end that has noir-tinged shadows that rival anything Gregg Toland shot for The Grapes of Wrath. Nor is the darkness used simply to indicate that times are darker, but it is actively drawn into the plot; one particularly effective scene watches as Jeeter plays, fascinated, with electric lamps in a hotel. As he leaves for the final, most sinful step in his quest for money, he pulls the cord on the lamp outside the porch, turning it off with such violence that he rips it off the building, plunging himself into darkness. A simple idea, made revelatory through its execution.

There's no shaking the feeling that Ford, Director of Visuals was working on a much soberer and more serious film than was Ford, Director of Actors. The first director made a film that I like a whole hell of a lot more. The amazing disconnect between the two halves of Tobacco Road make it one of the most intriguing films of the director's career, although hardly one of the most enjoyable and it positively reeks of only being suited to Ford completists, who are likelier to view it in the detached, scholarly mind that is vital to seeing it as anything other than a compendium of grating jokes.

And yet, this shrill hicksploitation, packed with lowest kind of humor outside of fart jokes, is graced with some of the loveliest and most thematically evocative imagery in the director's career, courtesy of three-time Oscar winning cinematographer Arthur Miller. That's not an easy claim to make of a filmmaker known for such rich visuals as Ford, and thus is the film's split personality: hacky, low-rent comedy mashed-up against sublime black-and-white cinematography that gives the barbaric content poetic resonance that it frankly doesn't deserve.

The script, such as it is, took a long and winding road to end up in America's cinemas in 1941: first, in 1932 the left-wing author Erskine Caldwell wrote a novel, a serious study of the literally penniless Lester family, sharecroppers driven to desperation as the worst years of the Great Depression bankrupted the owner of the family's land and left them unable to farm cotton as they had done for generations. The Lesters' behavior is selfish and sinful, but they are unable to do anything else, without the slightest hope of money in the future. The sober and unhappy book was adapted a year later by Jack Kirkland for the Broadway stage, where it ran for a record-setting 3182 consecutive performances over eight years.

Near the end of the play's run, Darryl Zanuck of 20th Century Fox commissioned a screenplay based on the stage version by Nunnally Johnson, fresh of off the much-heralded film adaptation of Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath, with the expectation that John Ford would direct (the third and final collaboration between the writer and director). Johnson and Ford elected to scrap the serious social criticism in the novel and play (perhaps fearing a retread of their most recent project?), and the new story, though superficially similar to its source material, is much lighter, offering fewer moments of moral introspection and more scenes of the Lesters screaming at each other.

The main arc of the film concerns Jeeter Lester (Charley Grapewin) and his wife Ada (Elizabeth Patterson), and their efforts to raise enough money to save their cotton farm for just one more season. Complicating life are the local religious busybody, Bessie Rice (Marjorie Rambeau), abusive son-in-law Lov Bensey (Ford's stock company stalwart Ward Bond), and the two Lester children still living at home, sex-starved 23-year-old Ellie Mae (Gene Tierney) and loud-mouthed, emotionally stunted 20-year-old Dude (William Tracy).

It's probably fair to say that what I dislike about the film isn't "the script" so much as it is "Dude." Somewhere along the line - whether in Johnson's screenplay, Ford's direction, or perhaps just something that Tracy brought to the character - Dude Lester manifested himself as a force of pure evil, hollering every single line and making obnoxious honking noises to show how much he loves cars. This is at least somewhat motivated, with the clearly unloving Jeeter treating his son like an animal and his son responding in kind as a howler monkey, but so unwatchable is the net result (and remember, this is supposed to be funny) that it would have been smarter to throw the whole edifice out and start fresh.

Dude is a microcosm for all that is wrong with the film: flat characters that are a cartoon of Southern ignorance more offensive and misguided than the most secluded ivory tower elitist should have been able to imagine. Just months after completing The Grapes of Wrath, I cannot fathom how John Ford found it in himself to attach his name to this project, as good as taking the noble and flawed and thoroughly realistic Joads and cramming them into a sub-par episode of Hee Haw. It bears repeating that dialect comedy was a longstanding element of Ford's art - it existed in his films at least as early as 1924's The Iron Horse, and that was even a silent movie - and it was often an uncomfortable element, sometimes loving and sometimes mocking, sometimes both within the same scene. But nothing I had ever seen by Ford prepared me for Tobacco Road and it's parade of the ugliest stereotypes about human behavior. There is quite literally nothing in the story worth saving - awful people behaving awfully and it's not even the tiniest bit amusing.

Then, there's the film's imagery, which is not merely worth saving, but apparently good enough to propel the film to the top 1000 films of all time, by at least one yardstick. Perhaps that's as it should be - cinema is visual, and Tobacco Road is a visual masterpiece for virtually every shot of its 84 minutes. On the simplest level, it's a pretty movie, full of frames you just want to grab and put on the wall, but it goes deeper than that. The leaf-dappled light on every surface is lovely to look at, but it's also a reflection how the characters are marked by the land, and it suggests that the land keeps the Lesters in perpetual half-light, the full sun being blocked by the natural world which once gave the family its livelihood.

As the story progresses, and Jeeter becomes more and more desperate in his attempts to beg, borrow or steal $100, the film grows progressively darker, culminating in a fifteen-minute sequence near the end that has noir-tinged shadows that rival anything Gregg Toland shot for The Grapes of Wrath. Nor is the darkness used simply to indicate that times are darker, but it is actively drawn into the plot; one particularly effective scene watches as Jeeter plays, fascinated, with electric lamps in a hotel. As he leaves for the final, most sinful step in his quest for money, he pulls the cord on the lamp outside the porch, turning it off with such violence that he rips it off the building, plunging himself into darkness. A simple idea, made revelatory through its execution.

There's no shaking the feeling that Ford, Director of Visuals was working on a much soberer and more serious film than was Ford, Director of Actors. The first director made a film that I like a whole hell of a lot more. The amazing disconnect between the two halves of Tobacco Road make it one of the most intriguing films of the director's career, although hardly one of the most enjoyable and it positively reeks of only being suited to Ford completists, who are likelier to view it in the detached, scholarly mind that is vital to seeing it as anything other than a compendium of grating jokes.