Mere oblivion

I am not about to ask whether Francis Ford Coppola is actually a good director or just a hack who got lucky a few times in the 1970s. Even his worst films - which, admittedly, well outnumber his best films - are unmistakably the work of a man in possession of overwhelming creativity and skill. So no, I don't think that the generally frustrating quality of his work over the last 25 years or so is proof that he's lost it, or that he never had it to begin with, or of anything other than a remarkable tendency towards overreach.

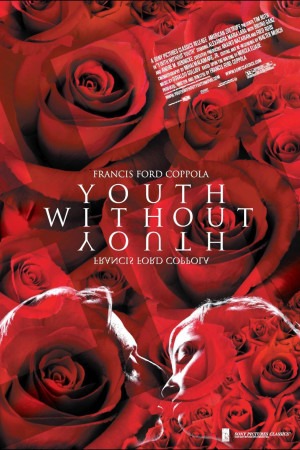

Instead, I find myself wondering on the occasion of Coppola's first official film as a director in ten years, Youth Without Youth, if the man might just be insane.

Coppola's last film, The Rainmaker, was a solid although not at all exceptional piece of procedural entertainment, which was enough to make it his best film of the '90s. It was a strangely impersonal film to lead into a decade-long sabbatical, though, and like everyone else, I had hoped that his time off would leave him rejuvenated and fresh to coming roaring back in full power, somewhat like his fellow '70s auteur Robert Altman did in 1992 with The Player, or like Altman did again in 2001 with Gosford Park. Instead, Youth Without Youth feels much more like Coppola's very own Prêt-à-Porter, or if I might jump over to yet another genius from the '70s who fell on hard times and self-parody, this is Coppola's Hollywood Ending, a boondoggle so obnoxious in concept and execution that it's hard to see why a theoretically intelligent filmmaker thought that it might be a good idea to try filming it in the first place.

Based on a story by Mircea Eliade, Youth Without Youth tells of Dominic Matei (Tim Roth), an elderly Romanian man who is struck by a bolt of lightning at the age of of 70, in 1938. He not only survives a theoretically fatal number of devastating burns and apparent blindness, but he appears, in every test that can be administered, to to have physically reverted to the age of 35 or 40. Under the care of the kindly Professor Stanciulescu (Bruno Ganz), Dominic slowly pieces together the ways in which his body has changed, giving him a strange set of mental skills such as telekinesis and the ability to read a book just by touching it. Meanwhile, he dodges the Nazis, who in their way hope to capture him for study, thinking that he might make a good test case in their quest to create the perfect man.

A decade and change later, Dominic is comfortably relocated in Geneva, living and not aging under a series of assumed names. One day in the mountains, he meets a young woman named Veronica, who looks uncannily like Dominic's long-ago fiancée Laura (maybe not so uncanny, as both women are played by the actress Alexandra Maria Lara). That afternoon, Veronica is - no contrivance here - struck by a bolt of lightning, sending her into a mental fugue where she believes herself to be an Indian ascetic priestess from 500 AD, speaking in flawless Sanskrit. No sooner does she come out of that trance and falls in love with Dominic than she begins, every night, to speak in dead languages, moving back in time: Egyptian, Sumerian, Babylonian. This is a boon for Dominic's research on a book meant to to explore the origins of all human culture, but when Veronica starts to age at an accelerated rate, things get a bit trickier.

Throughout, Dominic is followed by his mirror image. I mean that literally: his reflection is a callous, sneering presence, pushing Dominic into increasingly dark acts to preserve his anonymity and continue his research. If you recall the Gollum/Smeagol argument scene from The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, you have already seen this exact thing only done better.

If this had been presented as a straight-up melodrama, it might just have worked, and for one brief moment it looks like that might even be the case. The opening credits are a typically Coppolesque (Coppolan?) exercise in neo-classicism, consciously aping the credits style favored in American films from the '30s and '40s, down to the font choice. It's a promise of a similarly stylised feature that remains tragically unfulfilled. Not, dear God, that the film isn't stylised, but its style isn't nearly so gauche as the credits suggest, or as the the narrative requires.

Coppola and his team approach the script like its a religious text, and given the pervasive symbolism, references to Hindu texts, spiritual musing and the like, it might as well be. Every frame has been composed down to the micrometer, usually in very arch and self-important ways - one shot that leaps out for its dramatic overreach consists of Dominic's face in a mirror in the upper left, Laura facing the camera on the right, and a superimposed face of a professor of Asiatic languages (run with it) in the center. It crams a great deal of information into a very dense shot, but the information is kind of...stupid. Almost each and every frame is like that; oh, not with the crackpot Expressionism of a giant floating face, but so clearly Composed! that you can just about hear Coppola standing behind you and whispering the Meaning of Every Weighty Moment. In fact, it might be the one thing the film is good for: training people to unpack the thematic relevance of visuals. Because the themes are not subtle in this film, and the visuals that communicate the themes are not subtle either.

Which is to say, this is a very well-crafted film, but it appears to have been well-crafted by Satan's elves: it is packed to bursting with the most idiotic sort of flim-flam which is treated with the gravest sincerity. Imagine Orson Welles directing an Ed Wood script, or Wagner rewriting the score for Seussical, and you've pretty much nailed it down. That Coppola wrote the script means only that we get to blame him, instead of pity him.

The real perversity is that Tim Roth is fantastic in a role that really doesn't quite qualify as a "character" so much as a "voicepiece for symbolic musings about roses." He doesn't really dwell too much on what it might be like for a 70-year-old to wake up one day as an eternal 40-year-old, but the script doesn't give him room to, and what he does to make the romantic subplots work - for they do not on the page - is magnificent. It's a crying shame that he has this movie around that performance, because it's too painful to watch just for him, career-highlight or not.

The other perversity is that while nothing about Youth Without Youth works for even an instant, nevertheless the whole thing from top to bottom is extremely interesting; boring as it is, mindless as it is, aimless as it is, it's impossible to look away. That's Coppola's skill: making movies that simply leap of the screen and impose themselves upon you. I don't know if he's going to make a great film ever again, but I'm sure he'll make a better one than this, now that it's out of his system. Or maybe not. Either way, this mad wreck is proof of the director's genius even as it's proof of his incredible disregard for art or the audience.

Instead, I find myself wondering on the occasion of Coppola's first official film as a director in ten years, Youth Without Youth, if the man might just be insane.

Coppola's last film, The Rainmaker, was a solid although not at all exceptional piece of procedural entertainment, which was enough to make it his best film of the '90s. It was a strangely impersonal film to lead into a decade-long sabbatical, though, and like everyone else, I had hoped that his time off would leave him rejuvenated and fresh to coming roaring back in full power, somewhat like his fellow '70s auteur Robert Altman did in 1992 with The Player, or like Altman did again in 2001 with Gosford Park. Instead, Youth Without Youth feels much more like Coppola's very own Prêt-à-Porter, or if I might jump over to yet another genius from the '70s who fell on hard times and self-parody, this is Coppola's Hollywood Ending, a boondoggle so obnoxious in concept and execution that it's hard to see why a theoretically intelligent filmmaker thought that it might be a good idea to try filming it in the first place.

Based on a story by Mircea Eliade, Youth Without Youth tells of Dominic Matei (Tim Roth), an elderly Romanian man who is struck by a bolt of lightning at the age of of 70, in 1938. He not only survives a theoretically fatal number of devastating burns and apparent blindness, but he appears, in every test that can be administered, to to have physically reverted to the age of 35 or 40. Under the care of the kindly Professor Stanciulescu (Bruno Ganz), Dominic slowly pieces together the ways in which his body has changed, giving him a strange set of mental skills such as telekinesis and the ability to read a book just by touching it. Meanwhile, he dodges the Nazis, who in their way hope to capture him for study, thinking that he might make a good test case in their quest to create the perfect man.

A decade and change later, Dominic is comfortably relocated in Geneva, living and not aging under a series of assumed names. One day in the mountains, he meets a young woman named Veronica, who looks uncannily like Dominic's long-ago fiancée Laura (maybe not so uncanny, as both women are played by the actress Alexandra Maria Lara). That afternoon, Veronica is - no contrivance here - struck by a bolt of lightning, sending her into a mental fugue where she believes herself to be an Indian ascetic priestess from 500 AD, speaking in flawless Sanskrit. No sooner does she come out of that trance and falls in love with Dominic than she begins, every night, to speak in dead languages, moving back in time: Egyptian, Sumerian, Babylonian. This is a boon for Dominic's research on a book meant to to explore the origins of all human culture, but when Veronica starts to age at an accelerated rate, things get a bit trickier.

Throughout, Dominic is followed by his mirror image. I mean that literally: his reflection is a callous, sneering presence, pushing Dominic into increasingly dark acts to preserve his anonymity and continue his research. If you recall the Gollum/Smeagol argument scene from The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, you have already seen this exact thing only done better.

If this had been presented as a straight-up melodrama, it might just have worked, and for one brief moment it looks like that might even be the case. The opening credits are a typically Coppolesque (Coppolan?) exercise in neo-classicism, consciously aping the credits style favored in American films from the '30s and '40s, down to the font choice. It's a promise of a similarly stylised feature that remains tragically unfulfilled. Not, dear God, that the film isn't stylised, but its style isn't nearly so gauche as the credits suggest, or as the the narrative requires.

Coppola and his team approach the script like its a religious text, and given the pervasive symbolism, references to Hindu texts, spiritual musing and the like, it might as well be. Every frame has been composed down to the micrometer, usually in very arch and self-important ways - one shot that leaps out for its dramatic overreach consists of Dominic's face in a mirror in the upper left, Laura facing the camera on the right, and a superimposed face of a professor of Asiatic languages (run with it) in the center. It crams a great deal of information into a very dense shot, but the information is kind of...stupid. Almost each and every frame is like that; oh, not with the crackpot Expressionism of a giant floating face, but so clearly Composed! that you can just about hear Coppola standing behind you and whispering the Meaning of Every Weighty Moment. In fact, it might be the one thing the film is good for: training people to unpack the thematic relevance of visuals. Because the themes are not subtle in this film, and the visuals that communicate the themes are not subtle either.

Which is to say, this is a very well-crafted film, but it appears to have been well-crafted by Satan's elves: it is packed to bursting with the most idiotic sort of flim-flam which is treated with the gravest sincerity. Imagine Orson Welles directing an Ed Wood script, or Wagner rewriting the score for Seussical, and you've pretty much nailed it down. That Coppola wrote the script means only that we get to blame him, instead of pity him.

The real perversity is that Tim Roth is fantastic in a role that really doesn't quite qualify as a "character" so much as a "voicepiece for symbolic musings about roses." He doesn't really dwell too much on what it might be like for a 70-year-old to wake up one day as an eternal 40-year-old, but the script doesn't give him room to, and what he does to make the romantic subplots work - for they do not on the page - is magnificent. It's a crying shame that he has this movie around that performance, because it's too painful to watch just for him, career-highlight or not.

The other perversity is that while nothing about Youth Without Youth works for even an instant, nevertheless the whole thing from top to bottom is extremely interesting; boring as it is, mindless as it is, aimless as it is, it's impossible to look away. That's Coppola's skill: making movies that simply leap of the screen and impose themselves upon you. I don't know if he's going to make a great film ever again, but I'm sure he'll make a better one than this, now that it's out of his system. Or maybe not. Either way, this mad wreck is proof of the director's genius even as it's proof of his incredible disregard for art or the audience.