How civilized men behave

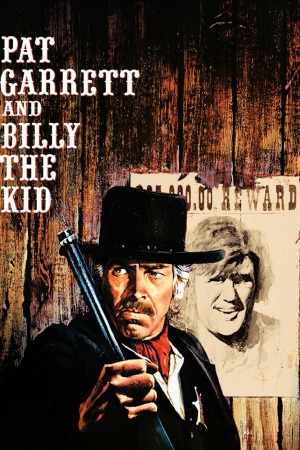

Outside of cinephiliac circles, it is my suspicion that these days, Sam Peckinpah's Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid is remembered - when it is remembered at all - largely as "that Dylan Western," or even "wow, I didn't know that 'Knockin' on Heaven's Door' was from a movie." And thanks to Todd Haynes and his cheerful, wholesale appropriation of the film's look for his new Dylan biopic I'm Not There, it seems that it may remain that way for a while yet.

A far better claim to fame, in my view, is that this would prove to be the final "real" Western that its director ever made in a career still best-known for westerns: primarily his generally-regarded masterpiece The Wild Bunch, but of the eight feature films he made prior to 1973 and Pat Garrett &c, five of them were set in some version of the Old West, typically at the end of the frontier era.

It was not just in their stories that these films were about the death of the frontier; it was in their very fabric of being. In Peckinpah's breakthrough, Ride the High Country, two Western legends, Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott (his final film), play two men near the ends of their lives, and the film is hence a referendum on the passing of one age of Western filmmaking into another; The Wild Bunch famously used extremely modern levels of explosive violence to bring the genre bloodily into the new Hollywood, no longer even recognisable as the playground of Hawks and Ford. Pat Garrett is similar to the latter of these in its level of violence, although it is not remotely so realistic - in fact it is more postmodern than modern, a feeling reinforced by the entirely characteristic score and songs composed for the film by Bob Dylan, an icon of the nascent Postmodern Era if ever there was one.

The story goes that Kris Kristofferson (playing the titular Kid) urged the director to hire Dylan to compose the film's theme song, and Peckinpah - having never heard any of Dylan's music - was so impressed that he commissioned the songwriter not just for a full soundtrack but also to play the small role of Billy's hanger-on, Alias. Peckinpah's filmmaking instinct was right on with this one: not that Dylan is so compelling as a performer (indeed, he's borderline insipid), but that it makes Pat Garrett "that Dylan Western." Admittedly, in 1973 it could just as easily have been called "that Kristofferson Western," but since that artist has gone on to prove himself an actor many times in the succeeding 34 years, the impact of his presence is much diluted. But Bob Dylan's is a face we're not used to seeing onscreen, and his persona, then and now, is so much more mythic than Kristofferson's that he stands out as A Statement: in the context of the film's cast, containing many instantly recognisable Western character actors in what amount to cameo roles, the presence of such an unmistakable, non-generic, pop-cultural face is a clear message that whatever lip service the film pays to classic Westerns, it is playing a much more subversive game than that.

Anyway, the film, which like so many Westerns old and new, treats upon one of the great pulp stories of fact-based American myth: the story of how William "Billy the Kid" Bonney was betrayed and hunted by his former colleague and newly-minted sheriff, Pat Garrett (James Coburn, yet another face of the '60s Zeitgeist). Billy was one of the great American anti-heroes, of course, not unlike Jesse James or Butch Cassidy, and Peckinpah, surprisingly, does not go very far in the direction of sticking a pin in that myth. While Billy is shown to be a violent man, he is no more violent than most of the people we meet in the film, and it's said that only one of his crimes is truly held against him, although that crime is a murder that he commits fairly early in the movie.

Instead, the film treats on that greatest of all Western subtexts: the not-quite-homoerotic attachment that dwells between men on the frontier. Garrett and Bonney were extremely close friends, we are told time and again, although when the film begins, they've already been divided by Garrett's new job as lawman; as the film progresses, we begin to see this manifest itself in the sheriff's Ahab-like devotion to catching Billy out of all the outlaws in New Mexico, his obsession feeling more and more like a spurned lover until the end, when he waits listening to Billy have sex, only bursting in when the other man is done and starting to get dressed again.

This is a story about Pat Garrett, although much of it is spent in the sole company of Billy: it is bookended by scenes of him getting shot (once, in a sepia-toned flash-forward set in 1909; then, after killing the outlaw, when he shoots his own image in a mirror), suggesting that it's ultimately his tragedy. He is the face of the New West, the tamed outlaw made a respectable lawman, trying to stamp out the last traces of his past, the wild Old West, and he is ultimately successful, although his success strands him in a role that he is not made for. It's a familiar trope, beyond a doubt, but done as well here as it has ever been done.

I do not know if Peckinpah felt that this would be his last go-round in the style that made him famous (although his next film would be the contemporary neo-Western Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia), but the tone is elegiac, more even than Ride the High Country. We sense it in the way that a familiar story and all those familiar character actors are compromised by the dour opening and the cartoonishly red blood, we sense it in the way that the director's customary slow-moving camera and glacial story development are cut into by the frequent scenes of violence (most of Peckinpah's work being noted for how little we actually see of the notorious violence, it is more than a little shocking just how many gunfights there are in Pat Garrett), and of course we sense it in the wailing notes of "Knockin' on Heaven's Door," a Dylan song now familiar to the point of cliché, but used in the film so sparingly, and so purposefully (making a significant appearance during the death scene of the film's most famous bit-player, Slim Pickens) that the whole song isn't even played within the movie. Some sources maintain that Peckinpah did not wish to use that song at all - the 1988 and 2005 "director's cuts" (this review is based on the latter) are more guesswork than their producers would like to admit, but it would be a terrible thing for the film to lose it.

So we have one of the most bittersweet films of Peckinpah's career: not leveling the myths of violence and male power, as he did so often, but engaging with the effect of those things on one man's life, a life that was ultimately taken away by his involvement with those myths, and the myth that grew up around his own life. It is not as excitingly cinematic as his greatest works, but it is more than strong enough to stand as one of the key texts of one of the great film careers.

A far better claim to fame, in my view, is that this would prove to be the final "real" Western that its director ever made in a career still best-known for westerns: primarily his generally-regarded masterpiece The Wild Bunch, but of the eight feature films he made prior to 1973 and Pat Garrett &c, five of them were set in some version of the Old West, typically at the end of the frontier era.

It was not just in their stories that these films were about the death of the frontier; it was in their very fabric of being. In Peckinpah's breakthrough, Ride the High Country, two Western legends, Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott (his final film), play two men near the ends of their lives, and the film is hence a referendum on the passing of one age of Western filmmaking into another; The Wild Bunch famously used extremely modern levels of explosive violence to bring the genre bloodily into the new Hollywood, no longer even recognisable as the playground of Hawks and Ford. Pat Garrett is similar to the latter of these in its level of violence, although it is not remotely so realistic - in fact it is more postmodern than modern, a feeling reinforced by the entirely characteristic score and songs composed for the film by Bob Dylan, an icon of the nascent Postmodern Era if ever there was one.

The story goes that Kris Kristofferson (playing the titular Kid) urged the director to hire Dylan to compose the film's theme song, and Peckinpah - having never heard any of Dylan's music - was so impressed that he commissioned the songwriter not just for a full soundtrack but also to play the small role of Billy's hanger-on, Alias. Peckinpah's filmmaking instinct was right on with this one: not that Dylan is so compelling as a performer (indeed, he's borderline insipid), but that it makes Pat Garrett "that Dylan Western." Admittedly, in 1973 it could just as easily have been called "that Kristofferson Western," but since that artist has gone on to prove himself an actor many times in the succeeding 34 years, the impact of his presence is much diluted. But Bob Dylan's is a face we're not used to seeing onscreen, and his persona, then and now, is so much more mythic than Kristofferson's that he stands out as A Statement: in the context of the film's cast, containing many instantly recognisable Western character actors in what amount to cameo roles, the presence of such an unmistakable, non-generic, pop-cultural face is a clear message that whatever lip service the film pays to classic Westerns, it is playing a much more subversive game than that.

Anyway, the film, which like so many Westerns old and new, treats upon one of the great pulp stories of fact-based American myth: the story of how William "Billy the Kid" Bonney was betrayed and hunted by his former colleague and newly-minted sheriff, Pat Garrett (James Coburn, yet another face of the '60s Zeitgeist). Billy was one of the great American anti-heroes, of course, not unlike Jesse James or Butch Cassidy, and Peckinpah, surprisingly, does not go very far in the direction of sticking a pin in that myth. While Billy is shown to be a violent man, he is no more violent than most of the people we meet in the film, and it's said that only one of his crimes is truly held against him, although that crime is a murder that he commits fairly early in the movie.

Instead, the film treats on that greatest of all Western subtexts: the not-quite-homoerotic attachment that dwells between men on the frontier. Garrett and Bonney were extremely close friends, we are told time and again, although when the film begins, they've already been divided by Garrett's new job as lawman; as the film progresses, we begin to see this manifest itself in the sheriff's Ahab-like devotion to catching Billy out of all the outlaws in New Mexico, his obsession feeling more and more like a spurned lover until the end, when he waits listening to Billy have sex, only bursting in when the other man is done and starting to get dressed again.

This is a story about Pat Garrett, although much of it is spent in the sole company of Billy: it is bookended by scenes of him getting shot (once, in a sepia-toned flash-forward set in 1909; then, after killing the outlaw, when he shoots his own image in a mirror), suggesting that it's ultimately his tragedy. He is the face of the New West, the tamed outlaw made a respectable lawman, trying to stamp out the last traces of his past, the wild Old West, and he is ultimately successful, although his success strands him in a role that he is not made for. It's a familiar trope, beyond a doubt, but done as well here as it has ever been done.

I do not know if Peckinpah felt that this would be his last go-round in the style that made him famous (although his next film would be the contemporary neo-Western Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia), but the tone is elegiac, more even than Ride the High Country. We sense it in the way that a familiar story and all those familiar character actors are compromised by the dour opening and the cartoonishly red blood, we sense it in the way that the director's customary slow-moving camera and glacial story development are cut into by the frequent scenes of violence (most of Peckinpah's work being noted for how little we actually see of the notorious violence, it is more than a little shocking just how many gunfights there are in Pat Garrett), and of course we sense it in the wailing notes of "Knockin' on Heaven's Door," a Dylan song now familiar to the point of cliché, but used in the film so sparingly, and so purposefully (making a significant appearance during the death scene of the film's most famous bit-player, Slim Pickens) that the whole song isn't even played within the movie. Some sources maintain that Peckinpah did not wish to use that song at all - the 1988 and 2005 "director's cuts" (this review is based on the latter) are more guesswork than their producers would like to admit, but it would be a terrible thing for the film to lose it.

So we have one of the most bittersweet films of Peckinpah's career: not leveling the myths of violence and male power, as he did so often, but engaging with the effect of those things on one man's life, a life that was ultimately taken away by his involvement with those myths, and the myth that grew up around his own life. It is not as excitingly cinematic as his greatest works, but it is more than strong enough to stand as one of the key texts of one of the great film careers.