The coward Robert Ford

In 1962, John Ford, the greatest and most important director of Westerns to ever live, closed the book on his favored genre with a single, incredibly famous line from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance: "This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend." That line was spoken by a newspaper reporter who was not prepared to allow inconvenient truths to get in the way of a good myth.

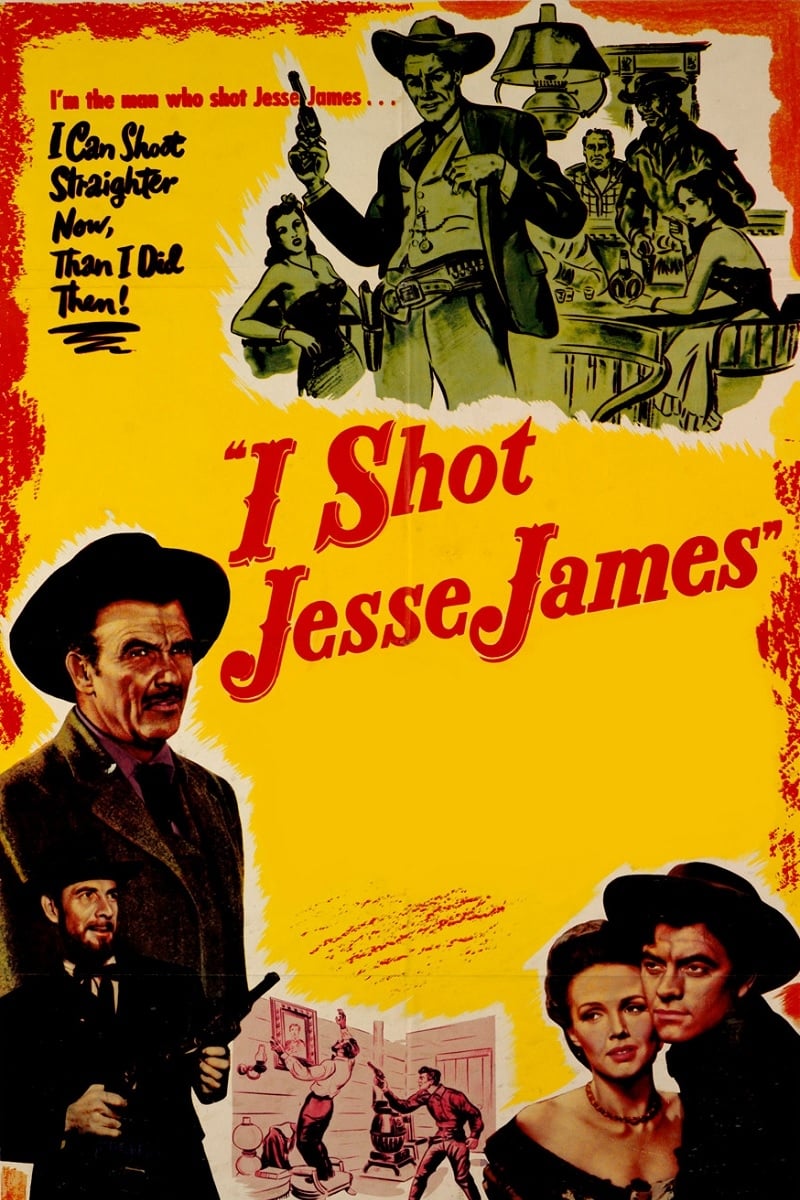

Thirteen years earlier, the finest newspaperman in the history of the cinema had already beaten him to the punch, in a film that took one of the most enduring Western myths of them all and stripped every last molecule of romanticism out of it: Samuel Fuller, making his directorial debut at 36 years of age with the knockout B-picture I Shot Jesse James.

By the time he started working on this project, it had been some nineteen years since a teenaged Sam Fuller got a job as reporter with the New York Journal, and the skills he learned then stuck with him for the rest of his life. From Pickup on South Street to White Dog, he always had a reporter's eye for documenting the comings and goings of people, with immediacy and urgency, making movies on the quick and dirty that would seem like trash if they weren't so aggressively honest.

In I Shot Jesse James, Fuller turns that reporter's eye to two of the most notorious men of their age, and deflates them down to human scale. In popular legend, Jesse James was the Robin Hood of the West, a great hero-scoundrel, and Robert Ford was his best friend, and a vile, cowardly plotter who killed Jesse in the most shameful and villainous way possible. The film is much more pragmatic: these are two criminals, one of whom killed the other for enough money to get out of being a criminal, and he felt kind of bad about it afterwards, but mostly because it didn't turn out to his advantage. Nothing mythic, just petty human drama.

The film's opening two shots do much to drive this point home. The first image we see after the studio logo is a wanted poster with a drawing of James's profile, offering $10,000 for his capture, dead or alive. The folk singer Robin Short starts singing the opening lines of the traditional "Ballad of Jesse James," so that the first words we hear in all the film are "Jesse James was a man and he killed many men."

There are two things going on here: first, Fuller wastes no time in reminding us that the hero Jesse James is a murderer and a thief. Second, both the ballad and the wanted poster are traditional iconography - they are part of the legend. This second meaning becomes important after the credits have ended (and such credits: panning off of the wanted poster to other posters on the wall with the names of the cast and crew, ending up at the wanted poster again. Besides being interesting and different, I like how it implicates the filmmakers in the mise en scène). From the wanted poster, on which Jesse faces to the left in profile, there's a whip cut to the right, and we see Jesse himself (Reed Hadley), on the left side of the frame and looking to the right. What we've seen is the iconic image of Jesse James being essentially destroyed (whip cuts are violent, yo) and replaced by the flesh-and-blood version of the same, and the flesh-and-blood version is a mean looking son of a bitch in this moment, as the camera tracks back and reveals that he's in the middle of robbing a bank.

From that moment on, Fuller will never once traffic in myth or greatness: the whole film will be about little men. One little man in particular: Bob Ford (John Ireland), whose murder of Jesse comes quite early on, about one-quarter of the way through the story, and happens for the blandest and most pragmatic of reasons: he needs money to marry a sexy showgirl (Barbara Britton), and he can get it quickly if he kills his friend, at the same time buying amnesty for his myriad crimes.

That Ford shoots James in the back is a sign of many things, and while cowardice is one of them, it's not overwhelming. On the simplest story level, Ford is aware that James would beat him in any other circumstance, and in this particular version of the story he's really not clever enough to think about this in moral terms, about how it's not a "fair fight" (indeed, this film's Bob Ford is quite dull-minded, always - always - reacting after he shoots James, never leading. Indeed, choosing to betray his friend is the only positive action he ever undertakes). There is also a strong homoerotic subtext, as the first moment that Ford nearly kills James is when he's bathing the other man's back in an oh-so-suggestive scene, proof once again that cheap genre films could always sneak more past the censors than tony studio fare. The moment when Ford shoots James is shot in many similar angles, and it's simply impossible to watch the one scene without thinking of the other. It's surely reading too much to think that Ford acts because he is full of self-loathing over his sexual urges, but the rest of the film flows a bit smoother if we think of him killing one "lover" to make room for another.*

It's after James's death that the film becomes something truly exceptional. Until now, it has simply been a revisionist history (although in 1949, that would have made it fairly radical). It tells a familiar story in different terms than we're used to. In the remaining hour, the film focuses with intimate detail upon Bob Ford's guilt, and his anger about being seen as a villain - particularly in two of the film's key scenes, the ones that most distinctly draw the line between the film as "reality" compared to the already-entrenched myths of the day: first, Ford plays himself in a dramatic re-enactment of the shooting, but when the time comes to shoot his prop gun at the fake Jesse, he flees; second, he demands that a roving troubadour sings the entirety of "The Ballad of Jesse James," even after the troubadour realises who his audience is.

The transition between these two parts of the film is an extraordinary sequence in which almost all of the plot of the film happens offscreen during a montage. Ford paces in his jail cell, as newspaper headlines are superimposed, detailing his trial, his sentencing, his stay of execution and his acquittal. Fuller the newspaperman must have enjoyed this little part, where the final component of the myth - the coward getting away scot-free - is brought up and disposed of in a few bold black words.

Instead of that story, the film spends the rest of its time exploring Bob Ford, humanising him (which is not to say that it makes him sympathetic, at least not consistently; for to be human is to be sometimes unbearable, non?), and watching him slowly realise that what happened was more than just him killing his best friend and later regretting it; he turned a paperback superstar into a martyr. In other words, Ford learns that he is part of a myth, and he finds it very hard to square with the fact that, in his own head, he is a person. In watching that person walk through that myth, Fuller points out the absurdity of the entire concept of modern myth-making, and kicks off the grand tradition of subversive neo-Westerns.

Now, it is only fair to mention that although it is a very solidly-directed film, it doesn't look like a Sam Fuller film (he wouldn't nail his signature style down for two more films). But as a first film, this nigh unto unimpeachable, and it feels every inch a Fuller project, even if it doesn't quite look the part. He was always an iconoclastic director, and it is well that he would start out his career by exploding an entire genre. Here was born a pulp maverick, and one of the greatest film directors in American history.

Thirteen years earlier, the finest newspaperman in the history of the cinema had already beaten him to the punch, in a film that took one of the most enduring Western myths of them all and stripped every last molecule of romanticism out of it: Samuel Fuller, making his directorial debut at 36 years of age with the knockout B-picture I Shot Jesse James.

By the time he started working on this project, it had been some nineteen years since a teenaged Sam Fuller got a job as reporter with the New York Journal, and the skills he learned then stuck with him for the rest of his life. From Pickup on South Street to White Dog, he always had a reporter's eye for documenting the comings and goings of people, with immediacy and urgency, making movies on the quick and dirty that would seem like trash if they weren't so aggressively honest.

In I Shot Jesse James, Fuller turns that reporter's eye to two of the most notorious men of their age, and deflates them down to human scale. In popular legend, Jesse James was the Robin Hood of the West, a great hero-scoundrel, and Robert Ford was his best friend, and a vile, cowardly plotter who killed Jesse in the most shameful and villainous way possible. The film is much more pragmatic: these are two criminals, one of whom killed the other for enough money to get out of being a criminal, and he felt kind of bad about it afterwards, but mostly because it didn't turn out to his advantage. Nothing mythic, just petty human drama.

The film's opening two shots do much to drive this point home. The first image we see after the studio logo is a wanted poster with a drawing of James's profile, offering $10,000 for his capture, dead or alive. The folk singer Robin Short starts singing the opening lines of the traditional "Ballad of Jesse James," so that the first words we hear in all the film are "Jesse James was a man and he killed many men."

There are two things going on here: first, Fuller wastes no time in reminding us that the hero Jesse James is a murderer and a thief. Second, both the ballad and the wanted poster are traditional iconography - they are part of the legend. This second meaning becomes important after the credits have ended (and such credits: panning off of the wanted poster to other posters on the wall with the names of the cast and crew, ending up at the wanted poster again. Besides being interesting and different, I like how it implicates the filmmakers in the mise en scène). From the wanted poster, on which Jesse faces to the left in profile, there's a whip cut to the right, and we see Jesse himself (Reed Hadley), on the left side of the frame and looking to the right. What we've seen is the iconic image of Jesse James being essentially destroyed (whip cuts are violent, yo) and replaced by the flesh-and-blood version of the same, and the flesh-and-blood version is a mean looking son of a bitch in this moment, as the camera tracks back and reveals that he's in the middle of robbing a bank.

From that moment on, Fuller will never once traffic in myth or greatness: the whole film will be about little men. One little man in particular: Bob Ford (John Ireland), whose murder of Jesse comes quite early on, about one-quarter of the way through the story, and happens for the blandest and most pragmatic of reasons: he needs money to marry a sexy showgirl (Barbara Britton), and he can get it quickly if he kills his friend, at the same time buying amnesty for his myriad crimes.

That Ford shoots James in the back is a sign of many things, and while cowardice is one of them, it's not overwhelming. On the simplest story level, Ford is aware that James would beat him in any other circumstance, and in this particular version of the story he's really not clever enough to think about this in moral terms, about how it's not a "fair fight" (indeed, this film's Bob Ford is quite dull-minded, always - always - reacting after he shoots James, never leading. Indeed, choosing to betray his friend is the only positive action he ever undertakes). There is also a strong homoerotic subtext, as the first moment that Ford nearly kills James is when he's bathing the other man's back in an oh-so-suggestive scene, proof once again that cheap genre films could always sneak more past the censors than tony studio fare. The moment when Ford shoots James is shot in many similar angles, and it's simply impossible to watch the one scene without thinking of the other. It's surely reading too much to think that Ford acts because he is full of self-loathing over his sexual urges, but the rest of the film flows a bit smoother if we think of him killing one "lover" to make room for another.*

It's after James's death that the film becomes something truly exceptional. Until now, it has simply been a revisionist history (although in 1949, that would have made it fairly radical). It tells a familiar story in different terms than we're used to. In the remaining hour, the film focuses with intimate detail upon Bob Ford's guilt, and his anger about being seen as a villain - particularly in two of the film's key scenes, the ones that most distinctly draw the line between the film as "reality" compared to the already-entrenched myths of the day: first, Ford plays himself in a dramatic re-enactment of the shooting, but when the time comes to shoot his prop gun at the fake Jesse, he flees; second, he demands that a roving troubadour sings the entirety of "The Ballad of Jesse James," even after the troubadour realises who his audience is.

The transition between these two parts of the film is an extraordinary sequence in which almost all of the plot of the film happens offscreen during a montage. Ford paces in his jail cell, as newspaper headlines are superimposed, detailing his trial, his sentencing, his stay of execution and his acquittal. Fuller the newspaperman must have enjoyed this little part, where the final component of the myth - the coward getting away scot-free - is brought up and disposed of in a few bold black words.

Instead of that story, the film spends the rest of its time exploring Bob Ford, humanising him (which is not to say that it makes him sympathetic, at least not consistently; for to be human is to be sometimes unbearable, non?), and watching him slowly realise that what happened was more than just him killing his best friend and later regretting it; he turned a paperback superstar into a martyr. In other words, Ford learns that he is part of a myth, and he finds it very hard to square with the fact that, in his own head, he is a person. In watching that person walk through that myth, Fuller points out the absurdity of the entire concept of modern myth-making, and kicks off the grand tradition of subversive neo-Westerns.

Now, it is only fair to mention that although it is a very solidly-directed film, it doesn't look like a Sam Fuller film (he wouldn't nail his signature style down for two more films). But as a first film, this nigh unto unimpeachable, and it feels every inch a Fuller project, even if it doesn't quite look the part. He was always an iconoclastic director, and it is well that he would start out his career by exploding an entire genre. Here was born a pulp maverick, and one of the greatest film directors in American history.