Fictional life based on factual death

It's received wisdom that there is no such thing as an anti-war movie, because movies make everything exciting, although like much received wisdom, that's a lie. I think that this has seemed to be the case at least in part precisely because the films we allow to tell us about warfare are made by well-meaning civilians. Is that a simplification? Yes, of course it is.

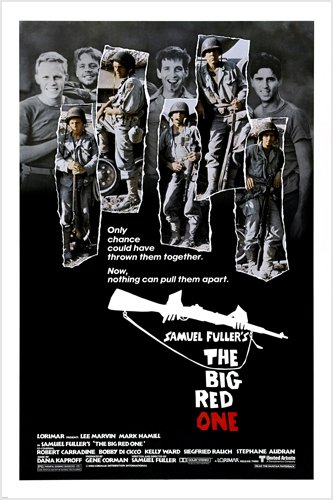

Nevertheless, it's the thought that I couldn't shake while watching The Big Red One the late, great Samuel Fuller's recounting of his experience fighting World War II from north Africa to Normandy: here is a film that is not at all exciting; that is, in fact, a little bit excruciating sometimes. Intriguingly, those points where it is most excruciating are its combat scenes, which are not all that bloody, and not all that visceral (in which respect, they are perhaps a relic of the film's tiny budget). They are, however, messy and chaotic and living. And noisy. Dear God, is this ever a noisy film, and that as much as anything is why it's anti-exciting in precise opposition to e.g. Saving Private Ryan, with its rousing gore effects. In The Big Red One, there are no sublime "ew!" moments to keep us amused even as we are horrified; there is only constant shrieking noise, and it's awful to listen to, and we just want it to STOP, which it never does.

Because of course, it never did. For the soldiers at the center of The Big Red One - and their creator, who lived through most of the incidents depicted in the film - combat is something to be endured. That's a hard thing to dramatise (who wants to sit through a movie where all of the action setpieces are endurance tests?), but Fuller makes it work here, largely because of the passionate, angry vitality he brings to the film. This is a living film full of living characters, and while messy human life is at the heart of all of Fuller's work, here it's the explicit and oft-vocalised theme: the glory of war is surviving, all that matters is being alive instead of being dead.

The core of this all-too-human drama are Pvt. Zab (Robert Carridine), Pvt. Vinci (Bobby Di Cicco), Pvt. Johnson (Kelly Ward), and Pvt. Griff, named for one of Fuller's war buddies who embodied for the director the idea of staying alive in the face of death and violence, played here by Mark Hamill. It's easy enough in 2007 (or 2004, the year of the film's long-awaited extended cut premiere) to think, "oh, Luke Skywalker," but this film was made in 1980, and shot in 1979; Star Wars was not merely a classic movie, it was still the bright central focal point of pop culture. Casting that film's star as a grunt in a grungy epic of war was, in that respect, quite the subversive act.

The other really important bit of casting was making Lee Marvin the unnamed Sergeant in the film's central role. Not because Marvin carried baggage with him, like Hamill; although there is a little bit of that, in the way that he represented the old edgy Hollywood style that Fuller himself came out of, and that The Big Red One calls back to. Rather, it's because Marvin is incandescently perfect in the role. This is the sort of character that could only be played by a pulpy actor, which makes sense given that it was written by a pulp auteur, but for all that it is a deeply layered role, and Marvin brings a sense of deep resignation and frustration that was already part of the character, but absolutely essential for the character to function. I do not know if nobody else could have played the part, but I know that Marvin played it to perfection.

In the meandering 162 minutes of the extended cut (I have not seen the 117 minute cut that Fuller signed off on in 1980), we get to know these five men very well, and see them as highly individual figures even as they remain essentially anonymous. To some degree, all of them are based on life as Sam Fuller experienced it between 1942 and 1945, and it shows, in all of the tiny character moments that feel too idiosyncratic and organic to be completely fictional. Most of The Big Red One is taken up with vignettes that show how these men function in the various shitholes that they are forced into, and while it's a dangerous temptation to recount all of the fascinating moments that make up the whole - that is, to recount the entire plot - I think I can safely get away with mentioning just one moment that leapt out at me: early in the film, the soldiers have dug down in foxholes to hide from German tanks, and as those tanks pass by, the sequestered Americans scream as loudly as they can. Fuller explained the import of this peculiar moment:

Nevertheless, it's the thought that I couldn't shake while watching The Big Red One the late, great Samuel Fuller's recounting of his experience fighting World War II from north Africa to Normandy: here is a film that is not at all exciting; that is, in fact, a little bit excruciating sometimes. Intriguingly, those points where it is most excruciating are its combat scenes, which are not all that bloody, and not all that visceral (in which respect, they are perhaps a relic of the film's tiny budget). They are, however, messy and chaotic and living. And noisy. Dear God, is this ever a noisy film, and that as much as anything is why it's anti-exciting in precise opposition to e.g. Saving Private Ryan, with its rousing gore effects. In The Big Red One, there are no sublime "ew!" moments to keep us amused even as we are horrified; there is only constant shrieking noise, and it's awful to listen to, and we just want it to STOP, which it never does.

Because of course, it never did. For the soldiers at the center of The Big Red One - and their creator, who lived through most of the incidents depicted in the film - combat is something to be endured. That's a hard thing to dramatise (who wants to sit through a movie where all of the action setpieces are endurance tests?), but Fuller makes it work here, largely because of the passionate, angry vitality he brings to the film. This is a living film full of living characters, and while messy human life is at the heart of all of Fuller's work, here it's the explicit and oft-vocalised theme: the glory of war is surviving, all that matters is being alive instead of being dead.

The core of this all-too-human drama are Pvt. Zab (Robert Carridine), Pvt. Vinci (Bobby Di Cicco), Pvt. Johnson (Kelly Ward), and Pvt. Griff, named for one of Fuller's war buddies who embodied for the director the idea of staying alive in the face of death and violence, played here by Mark Hamill. It's easy enough in 2007 (or 2004, the year of the film's long-awaited extended cut premiere) to think, "oh, Luke Skywalker," but this film was made in 1980, and shot in 1979; Star Wars was not merely a classic movie, it was still the bright central focal point of pop culture. Casting that film's star as a grunt in a grungy epic of war was, in that respect, quite the subversive act.

The other really important bit of casting was making Lee Marvin the unnamed Sergeant in the film's central role. Not because Marvin carried baggage with him, like Hamill; although there is a little bit of that, in the way that he represented the old edgy Hollywood style that Fuller himself came out of, and that The Big Red One calls back to. Rather, it's because Marvin is incandescently perfect in the role. This is the sort of character that could only be played by a pulpy actor, which makes sense given that it was written by a pulp auteur, but for all that it is a deeply layered role, and Marvin brings a sense of deep resignation and frustration that was already part of the character, but absolutely essential for the character to function. I do not know if nobody else could have played the part, but I know that Marvin played it to perfection.

In the meandering 162 minutes of the extended cut (I have not seen the 117 minute cut that Fuller signed off on in 1980), we get to know these five men very well, and see them as highly individual figures even as they remain essentially anonymous. To some degree, all of them are based on life as Sam Fuller experienced it between 1942 and 1945, and it shows, in all of the tiny character moments that feel too idiosyncratic and organic to be completely fictional. Most of The Big Red One is taken up with vignettes that show how these men function in the various shitholes that they are forced into, and while it's a dangerous temptation to recount all of the fascinating moments that make up the whole - that is, to recount the entire plot - I think I can safely get away with mentioning just one moment that leapt out at me: early in the film, the soldiers have dug down in foxholes to hide from German tanks, and as those tanks pass by, the sequestered Americans scream as loudly as they can. Fuller explained the import of this peculiar moment:

When we were in those holes, and the tanks were rolling over us, it was our only chance to scream all the terror out and not be heard. We got it all out in those holes.The whole damn film is like that. Personal observation bleeds out of every scene, and somehow it feels like a true story in a way that most war movies can't achieve. The Big Red One is a potent reminder that wars were fought by real young men, not by actors playing characters. Another piece of received wisdom: men who fought in war don't like to talk about it very much, and that's another reason that we mere noncombatants can ever understand what it was like. Samuel Fuller puts the lie to that: it might have hurt him to do so, but he shared his story with the world, in deeply respectful detail, and the giant, clumsy mess of a film that resulted is one of the most honest war films I have ever seen.