Night of a faun

Whenever people use the phrase "a fairy tale for grown-ups," I always get a little cranky, because it suggests something that is not true: that adults cannot watch fairy tales unless they have been tarted up. Adults like fantasy as much as anyone.

I think it's also mostly inaccurate, anyway. Nine times in ten, a "fairy tale for grown-ups" is adult only in terms of sex and violence, neither one of which matter very much if the story would insult a first grader.

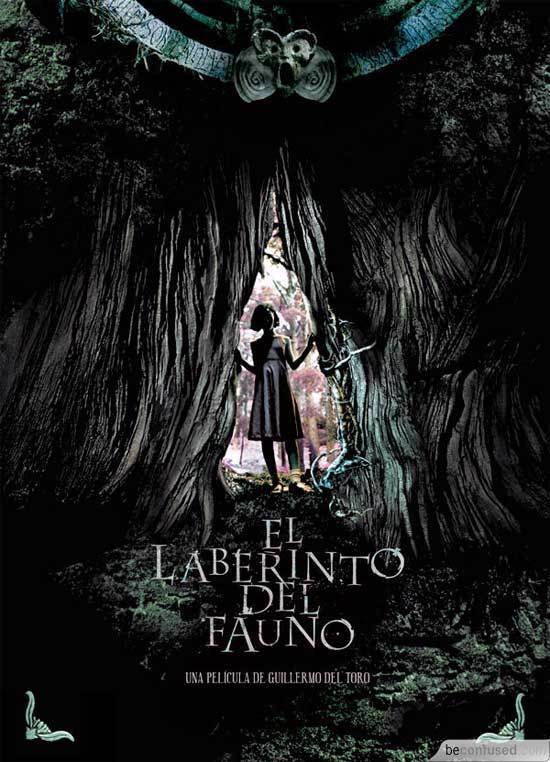

Which is why Guillermo del Toro's Pan's Labyrinth is so very welcome: it is most definitely a fairy tale that is most definitely not for children, and the reason for this is not just its dark tone, but also its extremely complex and difficult screenplay. Here is a fairy tale that delves into the nature of Fascism and the political history of Spain. No, I don't think we shall bring the kids to this one.

The story appears simple and straightforward, but there are so many delicate layers that an outline seems insulting. Nevertheless: Ofelia (Ivana Baquero) and her pregnant mother have just gone to live with Ofelia's new stepfather, Captain Vidal (Sergi López), of Franco's newly-victorious Fascist army. For most of its running time, Pan's Labyrinth treats on two extraordinarily different plot streams: in one, Vidal hunts the Resistance members living in the nearby woods while establishing Fascist control over the countryside; in the other, Ofelia receives instructions from an ancient Faun on the path to regain her birthright as a princess of the Underworld.

There's probably no literary genre more devoid of originality than fantasy, yet Pan's Labyrinth is full of surprises. I'm not going to hint at what they are - they wouldn't be surprises then! - but it's quite special how every time the plot twists in a direction you predicted from the very start, it immediately compensates by doing something unimaginable.

And for all that it's a lovely tale, I can't imagine that being anybody's primary take-away from the film. Because Pan's Labyrinth is probably the most wonderful-looking film of 2006, not just because of the shadowy, noir-like cinematography by Guillermo Navarro. Del Toro is a visionary, as they say, which translates as "whatever he's smoking, I want some." This is a film of hallucinogenic dream images, starting at the very design of two of the most perfectly-realised creatures in cinema history: the Faun and the Pale Man, both played by the American Doug Jones wearing an heroic amount of make-up, both the stuff of nightmares. So amazing are these figures that I feel the need to go ahead and show them right in the middle of my review:

The Pale Man

The Pale Man

This is exactly what a fairy tale is supposed to look like: the childhood Id. Let us never forget that children are rather brutal and nasty and capable of conceiving of any number of horrors, and del Toro has tapped right into that: if Terry Gilliam's Tideland earlier this year turned childhood nightmares into a baroque exercise in audience punishment,* Pan's Labyrinth is far more familiar and therefore terrifying. I've never had nightmares about the Pale Man, but I know what nightmares he reminds me of.

In fact, what makes del Toro's film so unnervingly effective is just how non-epic it is. The film is overwhelmingly domestic; Ofelia's quest is cast explicitly as a search for her family, and the film returns constantly to images of bedrooms and kitchens. The hearth and home are never far away, and each of Ofelia's missions are bookended by images and spaces that stress the prosaic and the non-fantastic (tiles on the floor, a muddied dress).

Of course, that's not even half of the movie: much of the plot is given over to Vidal, and his quest for power. It doesn't seem possible that del Toro could keep the fantasy and history plots up in the air simultaneously for as long as he does, but there is not a single moment where the story flags, where our interest falters. And this is the part of the film that is truly for adults, not only because the subject matter is somewhat esoteric, but because it is a visceral and harsh story. Perhaps it is to stress the fantastic elements of Ofelia's journey; perhaps it is the other way around; but any rate, this is an exceptionally violent movie, not in terms of quantity but in terms of impact. The physical destructibility of the human body is on full, terrifying display in this film, reaching more horrible dimensions as the story proceeds, reaching its apex in a moment that I will not spoil other than to proclaim that Pan's Labyrinth possesses the finest single make-up effect in the history of that art, and you'll know it when you see it.

Because of the ever-present threat of violent indignity on the human body, the film is fraught with tension, and del Toro exploits this fully in his attack on the Fascist mind. Vidal is a hollow man, able to function only in the presence of hierarchy, wherever he stands in it (this is literalised in a line that would bother me more if it weren't so well delivered). Hierarchy breeds power imbalances which breed fear, and Vidal uses this fear of his power to retain that very same power. He uses violence indiscriminately to legitimize his possession of power and keep the fear at a high pitch.

If the Fascist can only control using fear, Ofelia apparently represents the ability to rise over fear. In all her travails, she only experiences true fear once and even then is shown unambiguously to have a solid head on her shoulders, able to get herself out of a terrible situation with no harm. Imagination triumphs authoritarianism, because one can imagine the dictator losing power, and once that has been imagined it is inevitable that he shall.

Notice I said "apparently." Notice that the title to this post calls it a "near miss." As much as I dearly want Pan's Labyrinth to be one of the bestest things you ever did see, I can't quite get there, and this is why: I am not certain it quite connects all of its own dots. Not that I'm begging any film to spoon-feed its themes to me. Just that I half-wonder if I'm reading themes that aren't there; certainly the end of the film tends to cast doubt on my happy little reading, or at least permits it only in an ironic way.

Even more troubling, I fear, is the relationship between the two plots. For a very long time, the only reason for following both Vidal and Ofelia is that they are in the same physical environment. There is hardly intersection between the stories, and although a handful of motif recur in each - a key, a knife - I find it next to impossible to show that the stories are "parallel" in any way. Certainly, Ofelia doesn't "equal" Vidal, but who does? The faun? Is Ofelia meant to be the surrogate for the housekeeper/rebel agent Mercedes (Maribel Verdú)? Certain plot elements imply that's the case, except it makes no sense.

When one is dealing with symbolism as deep and layered as del Toro uses in Pan's Labyrinth, there is such a thing as too subtle (there's always such a thing as "too subtle," I suppose, but it's rarely to never achieved in the modern cinema). Frankly, I'm just not persuaded there's enough here to unlock the script, and although that doesn't usually bother me much, it's a very significant gap in a film as caught up in narrativity as this. I'm pretty sure I know where del Toro is going with the film; but I have to meet him a bit more than halfway to see it. None of which should imply that it's not stunning in each of its separate halves, nor that it's not a wonder and then some to behold. It's just, sadly, not a masterpiece. How's that for praising with faint damnation?

*And I'm not saying it did. In fact, I'm not saying anything about Tideland, except that it is profoundly out there.

I think it's also mostly inaccurate, anyway. Nine times in ten, a "fairy tale for grown-ups" is adult only in terms of sex and violence, neither one of which matter very much if the story would insult a first grader.

Which is why Guillermo del Toro's Pan's Labyrinth is so very welcome: it is most definitely a fairy tale that is most definitely not for children, and the reason for this is not just its dark tone, but also its extremely complex and difficult screenplay. Here is a fairy tale that delves into the nature of Fascism and the political history of Spain. No, I don't think we shall bring the kids to this one.

The story appears simple and straightforward, but there are so many delicate layers that an outline seems insulting. Nevertheless: Ofelia (Ivana Baquero) and her pregnant mother have just gone to live with Ofelia's new stepfather, Captain Vidal (Sergi López), of Franco's newly-victorious Fascist army. For most of its running time, Pan's Labyrinth treats on two extraordinarily different plot streams: in one, Vidal hunts the Resistance members living in the nearby woods while establishing Fascist control over the countryside; in the other, Ofelia receives instructions from an ancient Faun on the path to regain her birthright as a princess of the Underworld.

There's probably no literary genre more devoid of originality than fantasy, yet Pan's Labyrinth is full of surprises. I'm not going to hint at what they are - they wouldn't be surprises then! - but it's quite special how every time the plot twists in a direction you predicted from the very start, it immediately compensates by doing something unimaginable.

And for all that it's a lovely tale, I can't imagine that being anybody's primary take-away from the film. Because Pan's Labyrinth is probably the most wonderful-looking film of 2006, not just because of the shadowy, noir-like cinematography by Guillermo Navarro. Del Toro is a visionary, as they say, which translates as "whatever he's smoking, I want some." This is a film of hallucinogenic dream images, starting at the very design of two of the most perfectly-realised creatures in cinema history: the Faun and the Pale Man, both played by the American Doug Jones wearing an heroic amount of make-up, both the stuff of nightmares. So amazing are these figures that I feel the need to go ahead and show them right in the middle of my review:

The Pale Man

The Pale ManThis is exactly what a fairy tale is supposed to look like: the childhood Id. Let us never forget that children are rather brutal and nasty and capable of conceiving of any number of horrors, and del Toro has tapped right into that: if Terry Gilliam's Tideland earlier this year turned childhood nightmares into a baroque exercise in audience punishment,* Pan's Labyrinth is far more familiar and therefore terrifying. I've never had nightmares about the Pale Man, but I know what nightmares he reminds me of.

In fact, what makes del Toro's film so unnervingly effective is just how non-epic it is. The film is overwhelmingly domestic; Ofelia's quest is cast explicitly as a search for her family, and the film returns constantly to images of bedrooms and kitchens. The hearth and home are never far away, and each of Ofelia's missions are bookended by images and spaces that stress the prosaic and the non-fantastic (tiles on the floor, a muddied dress).

Of course, that's not even half of the movie: much of the plot is given over to Vidal, and his quest for power. It doesn't seem possible that del Toro could keep the fantasy and history plots up in the air simultaneously for as long as he does, but there is not a single moment where the story flags, where our interest falters. And this is the part of the film that is truly for adults, not only because the subject matter is somewhat esoteric, but because it is a visceral and harsh story. Perhaps it is to stress the fantastic elements of Ofelia's journey; perhaps it is the other way around; but any rate, this is an exceptionally violent movie, not in terms of quantity but in terms of impact. The physical destructibility of the human body is on full, terrifying display in this film, reaching more horrible dimensions as the story proceeds, reaching its apex in a moment that I will not spoil other than to proclaim that Pan's Labyrinth possesses the finest single make-up effect in the history of that art, and you'll know it when you see it.

Because of the ever-present threat of violent indignity on the human body, the film is fraught with tension, and del Toro exploits this fully in his attack on the Fascist mind. Vidal is a hollow man, able to function only in the presence of hierarchy, wherever he stands in it (this is literalised in a line that would bother me more if it weren't so well delivered). Hierarchy breeds power imbalances which breed fear, and Vidal uses this fear of his power to retain that very same power. He uses violence indiscriminately to legitimize his possession of power and keep the fear at a high pitch.

If the Fascist can only control using fear, Ofelia apparently represents the ability to rise over fear. In all her travails, she only experiences true fear once and even then is shown unambiguously to have a solid head on her shoulders, able to get herself out of a terrible situation with no harm. Imagination triumphs authoritarianism, because one can imagine the dictator losing power, and once that has been imagined it is inevitable that he shall.

Notice I said "apparently." Notice that the title to this post calls it a "near miss." As much as I dearly want Pan's Labyrinth to be one of the bestest things you ever did see, I can't quite get there, and this is why: I am not certain it quite connects all of its own dots. Not that I'm begging any film to spoon-feed its themes to me. Just that I half-wonder if I'm reading themes that aren't there; certainly the end of the film tends to cast doubt on my happy little reading, or at least permits it only in an ironic way.

Even more troubling, I fear, is the relationship between the two plots. For a very long time, the only reason for following both Vidal and Ofelia is that they are in the same physical environment. There is hardly intersection between the stories, and although a handful of motif recur in each - a key, a knife - I find it next to impossible to show that the stories are "parallel" in any way. Certainly, Ofelia doesn't "equal" Vidal, but who does? The faun? Is Ofelia meant to be the surrogate for the housekeeper/rebel agent Mercedes (Maribel Verdú)? Certain plot elements imply that's the case, except it makes no sense.

When one is dealing with symbolism as deep and layered as del Toro uses in Pan's Labyrinth, there is such a thing as too subtle (there's always such a thing as "too subtle," I suppose, but it's rarely to never achieved in the modern cinema). Frankly, I'm just not persuaded there's enough here to unlock the script, and although that doesn't usually bother me much, it's a very significant gap in a film as caught up in narrativity as this. I'm pretty sure I know where del Toro is going with the film; but I have to meet him a bit more than halfway to see it. None of which should imply that it's not stunning in each of its separate halves, nor that it's not a wonder and then some to behold. It's just, sadly, not a masterpiece. How's that for praising with faint damnation?

*And I'm not saying it did. In fact, I'm not saying anything about Tideland, except that it is profoundly out there.