It is not right to speak ill of the dead

Since Robert Altman died two months ago, I haven't had a chance to watch any of his films, either familiar to me or new, which is frankly a bit awful. After all, at the time of his death, he was the greatest American filmmaker.

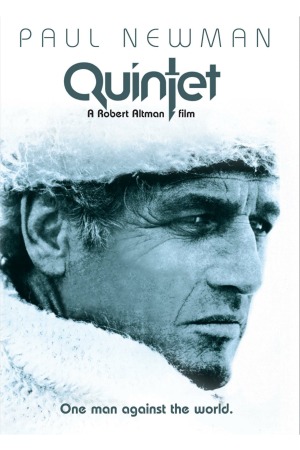

Last night, I finally had my chance to watch either The Long Goodbye or Quintet, neither one of which I've ever seen. And despite how much I'm aware that I can't really count myself a fan of the director, or of the genre of film noir, without seeing the former, it's been written about so much in so many places that it seemed presumptuous of me to try adding anything. Besides, I think the old man would have been pleased, in a way, that I chose to belatedly honor his life and death with a film that vies only with H.E.A.L.T.H for the title of his most-reviled project.

Quintet is often erroneously called a "bad" movie, when it is actually just an unmitigated failure. A bad movie has no interesting ideas whatsoever, and is created by indifferent filmmakers who just want to finish up and cash their paycheck. The one thing that can never be said of Quintet is that it wants for ideas. It has a superfluity of ideas, more ideas than any other science fiction film of the 1970s. Altman was clearly invested in the film deeply, filling it full of tiny details and grand themes and generally pouring himself into it. Unfortunately, because of all these ideas, Quintet is totally incoherent.

(I'll get this out of the way right now: I've heard it defended that the film is a parody of Bergman and/or Antonioni. That is the most idiotic thing I've ever heard, although I can kind of see how you'd get there if you'd only ever seen Quintet when you were stoned).

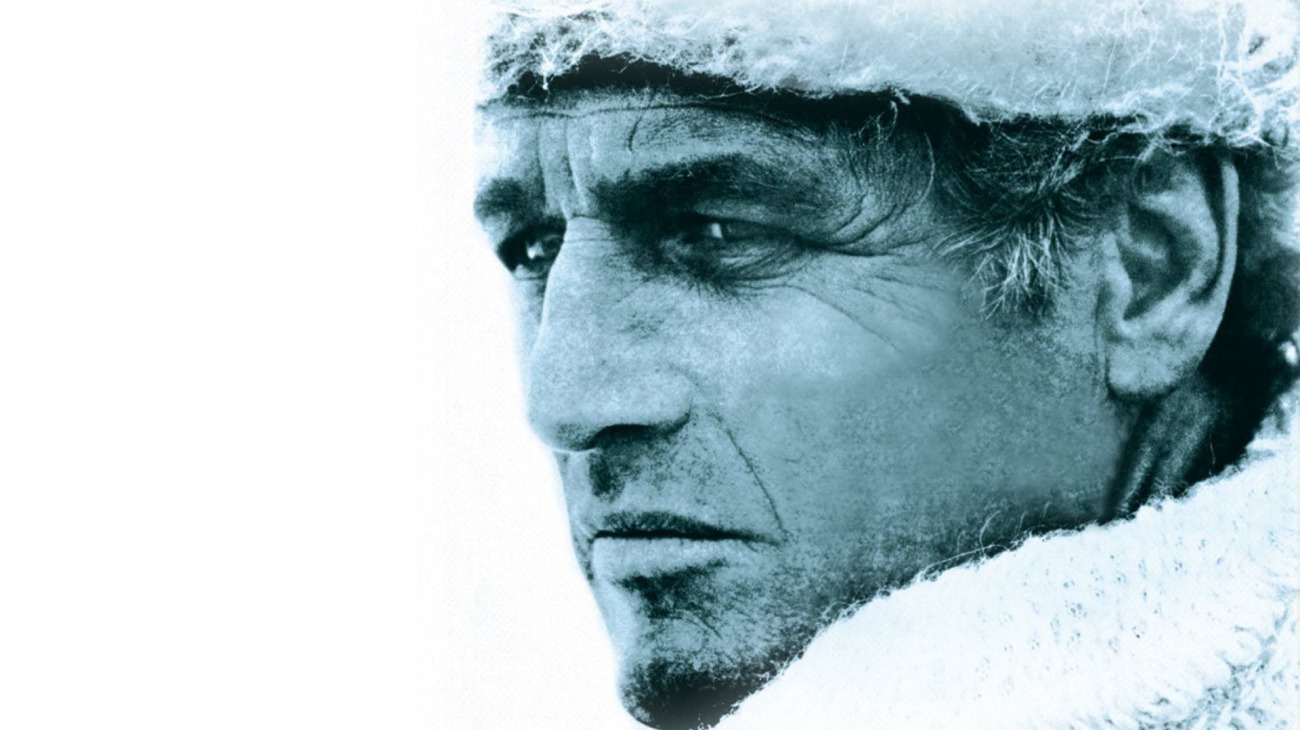

The movie opens big: there is a blinding white field of snow, with two figures dressed in white trudging through it. Now, the temperature was in the 'teens outside while I was watching this, but even in the dead of summer I think this would be true: it is a cold film. Ice and snow are everywhere, and most of the time you can see the actors' breath, and the horrible chill seeps right out of the television (or off of the screen, if it is 1979 and you are easily separated from your money) into your bones. The film was shot in a Montreal winter, and it pays off handsomely. From the first frame, this is a resolutely tactile film, and considering how important the setting will be to what goes on later, this is important.

Now something happens, and "Quintet-the-masterpiece-of-place" gives way to "Quintet-teh-batshit-crazy." Over a period of some twenty seconds, the music, by Tom Pierson (his only original score ever), starts to fade in. Two thoughts occur at this moment:

1) Have I ever seen an Altman film with a musical score?

2) If Stravinsky wrote music for Mannheim Steamroller to play, that would sound exactly like this.

After this, I won't mention the score, but it's not because there's nothing to return to. The score is fairly aggressive, in fact, and it's fucking weird. Generically, I have no idea what to call it, but in terms of the movie, it crops up at random places, blares about rather loudly, fails entirely to match whatever emotional moment is going on, and stops. It's just a part of the mighty tapestry that is the weirdness of Quintet, and I will be discussing that shortly.

Those two figures in white are shortly revealed to be Essex (Paul Newman) and Vivia (Brigitte Fossey), apparently his wife. Vivia notices a Canadian goose in the sky, and both are thrilled to see this rare animal for the first time in years. As they discuss the goose and other things, we begin to put together a picture: they are headed for "the city," the only outpost of life in this entire wasteland of snow; Essex once lived there but left for private reasons; the whole world is like this. When the draw near the city, the find dead bodies scattered around, with packs of wild dobermans feeding off of the corpses.

I have to be totally honest: for the first twenty minutes or so, bringing them to the entrance to the city, I was actually rather impressed & wondering what was so infamous about this film as to lend it the dark reputation it holds. There's little denying that it's impressive to look at: the film has that swell '70s sci-fi look where everything is washed-out and white, and this sells the idea of a post-holocaust world much better than dialogue ever could. Which is not to say that the dialogue tries: there is very little exposition at all about the world of the film, only about the bits that characters plausibly would not know (i.e. it's all "tell me about your family" and not "ah, so this post-nuclear world of ours..." In fact, the nature of the ice age is never explained). I haven't praise enough for this: it's natural, and it makes the viewer pay attention, and just on the face of it, I hate films that spoon-feed everything to the audience. Not to mention that the world which so slowly reveals itself is actually rather interesting, if you care for stark, hopeless post-apocalyptic sci-fi (Altman clearly does, the magnificent cynic).

When Essex and Vivia enter the city, Quintet goes off the rails completely, both as a story and visually. Immediately upon their arrival, Essex goes to a room full of tall, narrow sheets of crystal that slowly turn around. For several minutes, we thrill as he walks around and looks at them. Eventually, we figure out that this is a city directory, but that only raises more questions, like how the hell does it work. And yet, this scene still make more sense intuitively than almost everything that follows it.

Cutting to the chase: a man in black bombs the home of Essex's brother Francha, killing several people including Vivia, and Essex goes on a quest for vengeance that leads him to a list with six people, among them Francha. Meanwhile, a great deal of time is spent in the city casino, where the only game around is Quintet, a dice game played by five people plus one, whose rules are impossible to glean, and that is significant, because Quintet isn't just the game and the film's title, it's a metaphor for the meaning of the film, and if the game makes no sense (and it doesn't), the movie pretty much has no ability to make sense.

Things on the back of the video box are traditionally not treated as spoilers, so I feel free to give away the end-of-film reveal that the list of people refers to a real-world game of Quintet, whose players include Saint Christopher (Vittorio Gassman) and Ambrosia (Bibi Andersson) and ultimately Essex himself, with the casino adjudicator Grigor (Fernando Rey) serving as the game's referee. The winner is the last one alive.

Here is what I have learned about Quintet: it has actual rules and is playable, and it was invented by Robert Altman during the backgammon fad of the late 1970s. I cannot say if Quintet hastened the end of that craze, but I do know that any fad capable of producing a movie like this one is nearer the end of its life than the beginning.

Words fail me to describe the bravery and arrogance involved in structuring a movie after a game you've invented and nobody has ever played. But that is precisely what Altman has done, as far as I can tell. This is not the sign of a "bad" film. This is the sign of a film made by a genius running headlong into a great many different psychoactive substances, if the rumors are true. It takes brilliance to make such a colossal error in judgment.

That's just the plot. Everything else goes nuts at the same time the script does: when Essex and Vivia enter the city. The film was shot in the Man and His World Pavilion built for Expo 67 on Île Sainte-Hélène in Montreal, and subsequently left to decay on its own. When Altman's crew arrived, it was to find a dim grey space that I simply cannot describe. Nor can I find pictures. Let us say that it looks like Star Trek and Blade Runner had a child together, and leave it at that.

This is already a strange-looking place, not at all what you'd end up with if, say, a production designer for a major film had conceived of it, and to make sure we're thoroughly disoriented, Altman has taken the extra step of smearing Vaseline on the edges of the lens, so that every interior shot (which is to say, 85% of the film) is less a 1.85 : 1 rectangle, but rather an oval with blurry corners.

A day later, I still don't have the slightest idea what Altman was trying to accomplish with the look of this film. To be honest, it's not as much an aberration as it seems: it's rather similar in effect if not in technique to 3 Women, the director's last film in 1979. In that movie, constant soft focus and diffusion is used to create the sense that we are watching a dream or a hallucination, and it is brilliantly effective. Perhaps that is the same goal that Altman had for the diffusion in Quintet. Perhaps it is not.

"Perhaps/perhaps not" casts its shadow over every moment of the film. Individually, it's possible to figure out what every element might mean, but it's never certain, and none of it hangs together. This is a film of grand ideas by a smart man, but those ideas are never put in a framework that is remotely accessible (a framework based on an invented board game is perhaps the most arcane framework in the history of American movies). So many striking images lead to so many frustrating questions: why bother with such elaborately gory deaths (and there are several, slash-grade deaths, something at complete odds with the rest of the Altman canon)? Why are there so many pentagons - is the whole culture based on Quintet, or is it just for our benefit? What's with the Euro-art cast? How do the dogs get inside? Or is it outside? And what, exactly, led to the ice age?

So getting back to what I said at the beginning: this is not a bad movie. It is a failed movie. It has no effect on the viewer, and I do not quite understand what the effect is meant to be in the first place. There is no logic to the events film beyond the fact that a person decided that they should all be put together. And that's what's so interesting: someone was very careful about every inch of this film. It's in no way sloppy; just impossible to comprehend for anyone who isn't Robert Altman in 1979. The totality of its failure to cohere in any way is quite stunning and even attractive. I highly recommend watching the film precisely one time, to bask in the epic scale of its egocentric chaos. It is alien to everything human, but impossibly arresting, perhaps for that exact reason. And perhaps not.

Last night, I finally had my chance to watch either The Long Goodbye or Quintet, neither one of which I've ever seen. And despite how much I'm aware that I can't really count myself a fan of the director, or of the genre of film noir, without seeing the former, it's been written about so much in so many places that it seemed presumptuous of me to try adding anything. Besides, I think the old man would have been pleased, in a way, that I chose to belatedly honor his life and death with a film that vies only with H.E.A.L.T.H for the title of his most-reviled project.

Quintet is often erroneously called a "bad" movie, when it is actually just an unmitigated failure. A bad movie has no interesting ideas whatsoever, and is created by indifferent filmmakers who just want to finish up and cash their paycheck. The one thing that can never be said of Quintet is that it wants for ideas. It has a superfluity of ideas, more ideas than any other science fiction film of the 1970s. Altman was clearly invested in the film deeply, filling it full of tiny details and grand themes and generally pouring himself into it. Unfortunately, because of all these ideas, Quintet is totally incoherent.

(I'll get this out of the way right now: I've heard it defended that the film is a parody of Bergman and/or Antonioni. That is the most idiotic thing I've ever heard, although I can kind of see how you'd get there if you'd only ever seen Quintet when you were stoned).

The movie opens big: there is a blinding white field of snow, with two figures dressed in white trudging through it. Now, the temperature was in the 'teens outside while I was watching this, but even in the dead of summer I think this would be true: it is a cold film. Ice and snow are everywhere, and most of the time you can see the actors' breath, and the horrible chill seeps right out of the television (or off of the screen, if it is 1979 and you are easily separated from your money) into your bones. The film was shot in a Montreal winter, and it pays off handsomely. From the first frame, this is a resolutely tactile film, and considering how important the setting will be to what goes on later, this is important.

Now something happens, and "Quintet-the-masterpiece-of-place" gives way to "Quintet-teh-batshit-crazy." Over a period of some twenty seconds, the music, by Tom Pierson (his only original score ever), starts to fade in. Two thoughts occur at this moment:

1) Have I ever seen an Altman film with a musical score?

2) If Stravinsky wrote music for Mannheim Steamroller to play, that would sound exactly like this.

After this, I won't mention the score, but it's not because there's nothing to return to. The score is fairly aggressive, in fact, and it's fucking weird. Generically, I have no idea what to call it, but in terms of the movie, it crops up at random places, blares about rather loudly, fails entirely to match whatever emotional moment is going on, and stops. It's just a part of the mighty tapestry that is the weirdness of Quintet, and I will be discussing that shortly.

Those two figures in white are shortly revealed to be Essex (Paul Newman) and Vivia (Brigitte Fossey), apparently his wife. Vivia notices a Canadian goose in the sky, and both are thrilled to see this rare animal for the first time in years. As they discuss the goose and other things, we begin to put together a picture: they are headed for "the city," the only outpost of life in this entire wasteland of snow; Essex once lived there but left for private reasons; the whole world is like this. When the draw near the city, the find dead bodies scattered around, with packs of wild dobermans feeding off of the corpses.

I have to be totally honest: for the first twenty minutes or so, bringing them to the entrance to the city, I was actually rather impressed & wondering what was so infamous about this film as to lend it the dark reputation it holds. There's little denying that it's impressive to look at: the film has that swell '70s sci-fi look where everything is washed-out and white, and this sells the idea of a post-holocaust world much better than dialogue ever could. Which is not to say that the dialogue tries: there is very little exposition at all about the world of the film, only about the bits that characters plausibly would not know (i.e. it's all "tell me about your family" and not "ah, so this post-nuclear world of ours..." In fact, the nature of the ice age is never explained). I haven't praise enough for this: it's natural, and it makes the viewer pay attention, and just on the face of it, I hate films that spoon-feed everything to the audience. Not to mention that the world which so slowly reveals itself is actually rather interesting, if you care for stark, hopeless post-apocalyptic sci-fi (Altman clearly does, the magnificent cynic).

When Essex and Vivia enter the city, Quintet goes off the rails completely, both as a story and visually. Immediately upon their arrival, Essex goes to a room full of tall, narrow sheets of crystal that slowly turn around. For several minutes, we thrill as he walks around and looks at them. Eventually, we figure out that this is a city directory, but that only raises more questions, like how the hell does it work. And yet, this scene still make more sense intuitively than almost everything that follows it.

Cutting to the chase: a man in black bombs the home of Essex's brother Francha, killing several people including Vivia, and Essex goes on a quest for vengeance that leads him to a list with six people, among them Francha. Meanwhile, a great deal of time is spent in the city casino, where the only game around is Quintet, a dice game played by five people plus one, whose rules are impossible to glean, and that is significant, because Quintet isn't just the game and the film's title, it's a metaphor for the meaning of the film, and if the game makes no sense (and it doesn't), the movie pretty much has no ability to make sense.

Things on the back of the video box are traditionally not treated as spoilers, so I feel free to give away the end-of-film reveal that the list of people refers to a real-world game of Quintet, whose players include Saint Christopher (Vittorio Gassman) and Ambrosia (Bibi Andersson) and ultimately Essex himself, with the casino adjudicator Grigor (Fernando Rey) serving as the game's referee. The winner is the last one alive.

Here is what I have learned about Quintet: it has actual rules and is playable, and it was invented by Robert Altman during the backgammon fad of the late 1970s. I cannot say if Quintet hastened the end of that craze, but I do know that any fad capable of producing a movie like this one is nearer the end of its life than the beginning.

Words fail me to describe the bravery and arrogance involved in structuring a movie after a game you've invented and nobody has ever played. But that is precisely what Altman has done, as far as I can tell. This is not the sign of a "bad" film. This is the sign of a film made by a genius running headlong into a great many different psychoactive substances, if the rumors are true. It takes brilliance to make such a colossal error in judgment.

That's just the plot. Everything else goes nuts at the same time the script does: when Essex and Vivia enter the city. The film was shot in the Man and His World Pavilion built for Expo 67 on Île Sainte-Hélène in Montreal, and subsequently left to decay on its own. When Altman's crew arrived, it was to find a dim grey space that I simply cannot describe. Nor can I find pictures. Let us say that it looks like Star Trek and Blade Runner had a child together, and leave it at that.

This is already a strange-looking place, not at all what you'd end up with if, say, a production designer for a major film had conceived of it, and to make sure we're thoroughly disoriented, Altman has taken the extra step of smearing Vaseline on the edges of the lens, so that every interior shot (which is to say, 85% of the film) is less a 1.85 : 1 rectangle, but rather an oval with blurry corners.

A day later, I still don't have the slightest idea what Altman was trying to accomplish with the look of this film. To be honest, it's not as much an aberration as it seems: it's rather similar in effect if not in technique to 3 Women, the director's last film in 1979. In that movie, constant soft focus and diffusion is used to create the sense that we are watching a dream or a hallucination, and it is brilliantly effective. Perhaps that is the same goal that Altman had for the diffusion in Quintet. Perhaps it is not.

"Perhaps/perhaps not" casts its shadow over every moment of the film. Individually, it's possible to figure out what every element might mean, but it's never certain, and none of it hangs together. This is a film of grand ideas by a smart man, but those ideas are never put in a framework that is remotely accessible (a framework based on an invented board game is perhaps the most arcane framework in the history of American movies). So many striking images lead to so many frustrating questions: why bother with such elaborately gory deaths (and there are several, slash-grade deaths, something at complete odds with the rest of the Altman canon)? Why are there so many pentagons - is the whole culture based on Quintet, or is it just for our benefit? What's with the Euro-art cast? How do the dogs get inside? Or is it outside? And what, exactly, led to the ice age?

So getting back to what I said at the beginning: this is not a bad movie. It is a failed movie. It has no effect on the viewer, and I do not quite understand what the effect is meant to be in the first place. There is no logic to the events film beyond the fact that a person decided that they should all be put together. And that's what's so interesting: someone was very careful about every inch of this film. It's in no way sloppy; just impossible to comprehend for anyone who isn't Robert Altman in 1979. The totality of its failure to cohere in any way is quite stunning and even attractive. I highly recommend watching the film precisely one time, to bask in the epic scale of its egocentric chaos. It is alien to everything human, but impossibly arresting, perhaps for that exact reason. And perhaps not.