Chance is a fool's name for fate

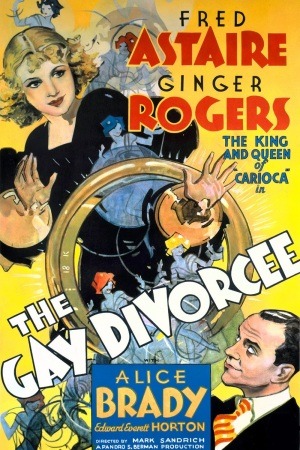

In 1934, a year after accidentally (or not) becoming a pair of stars in Flying Down to Rio, Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers were re-teamed for the first proper "Fred & Ginger movie," The Gay Divorcee. "La Carioca" be damned: this is where most of the elements that we associate with their cycle of films in hindsight first appeared.

To begin, its plot: Fred plays Guy Holden, a famous American dancer who meets Ginger's Mimi Glossop by accident on a London dock where he is awkward and jackassy, she is frigid, he stalks her, he dances with her one time and it's so insanely beautiful that she falls in love on the spot. This plot will recur in...all of them? Absent the character names, and the London docks.

The micro-plot is taken from Gay Divorce, a Cole Porter musical which Astaire starred in on Broadway (the Hays office demanded the title change, although the bawdy double-entendres of the book were let alone; such freedom would not long remain a part of the Astaire & Rogers canon). Mimi is married, as it turns out, and she hires English lawyer Egbert Fitzgerald (Edward Everett Horton, in his first of three films with the duo) to help her arrange a fake liaison so that she can be divorced on the grounds of adultery. Tragically, she never meets the co-respondent Egbert arranges for, Rodolfo Tonetti (Erik Rhodes of the stage version; he would bring the same deeply unprogressive Italian caricature to Top Hat), and believes that Guy has been assigned to the case. She invites him to her room, where innuendos and hijinks ensue.

From the start, Fred and Ginger had unmistakable chemistry onscreen, and although her wise-ass persona had been tamed from the previous year, Ginger was still at heart a comedienne. Which goes a long way to explain, despite a farcical plot that shows every one of its seams, The Gay Divorcee works completely as a comedy. It doesn't hurt that the supporting cast includes three great comic character actors: Horton, of course, as well as Alice Brady playing Ginger's scatterbrained aunt and Eric Blore (his second of five trips with the duo, given infinitely more to do than in Flying Down to Rio) as a bothersome waiter. Everyone fires on all cylinders, there's some genuinely great dialogue, so who cares if the resolution can be spotted as soon as the credits stop rolling? As overseen by the unjustly forgotten, prematurely deceased director Mark Sandrich (another first! He'd go on to direct four more films for the team), it's actually a really high-caliber pre-screwball comedy, and one of a very small number of Astaire-Rogers films that would work almost as well if the songs were taken out entirely.

Of course, part of that has to do with the generally low-quality of the numbers. The film has scuttled almost all of the original Cole Porter soundtrack in favor of songs by Harry Revel & Mack Gordon and Con Conrad & Herb Magidson, and this qualifies as a trade-down. Cole Porter to most people would qualify as a trade-down, of course, but his one included song, "Night and Day," sticks out like a sore thumb. More on that shortly.

The first number, "Don't Let It Bother You," opens things off well enough; a chorus of Parisian (cough) girls singing with some really strange choreography involving doing the can-can with their hands, clad in dolls' clothes. The payoff is when a doll-hand does a bit of jazz hoofing and we find - surprise! - it belongs to Astaire. And then a ridiculous plot contrivance that I do not wish to share brings Fred to the dance floor, where he knocks out a bit of jazzy tapping. It's well-done (it's Fred Astaire), but it's perfunctory and has a distinctly pornographic feeling, like it was just shoved in because that's what we want to see.

Still, it's better than the second and third dances. "A Needle in a Haystack" involves Fred...dressing to music. Yeah. It might be the most pointless solo number in all of his RKO films, and the awful song doesn't help. Moving along: "Let's K-nock K-neez" is something of a novelty song, in that it is performed not by Astaire, nor by Rogers, but by Edward Everett Horton. Wearing a black wife-beater, tiny shorts, and sandals with socks. If you are not intimately familiar with 1930s comedies and do not know off hand what he looks like, it is beyond horror. Images are hard to find on the internet, and for good reason, and I do not intend to contribute one. Also, his singing voice is bad. For no reason other than she was a contracted ingenue, Betty Grable duets with Horton. It's so surreal, I can't even tell you.

And then, there's "Night and Day." It has been said that if Astaire and Rogers never performed another dance together, their place in film history would have been cemented with this song. I'm in no mood to disagree. It's another first for the series, and a much more important one: this is the first major dance to fulfill Fred's desire that no dance be mere spectacle, but instead forward the plot and character development of the film. Boy, does it ever. Mimi goes into the dance hating Guy and just trying not to make a scene, and at the end of it, she's in love. What's amazing about this number, compared to everything else in Hollywood at the time, is how well it's acted (this, I think, goes to the heart of why Ginger was Fred's greatest partner). Look at Rogers' stiffness, her to-this-point reasonable fear of Guy. Look at Astaire's desperate need to hold her close. This is right up with "Cheek to Cheek" and "Never Gonna Dance" as one of their greatest collaborations.

Unfortunately, there's one more song to come, and while it is Fred and Ginger again, it's also every damn day player at RKO. The dance is to the first-ever winner of the Best Song Oscar, "The Continental," but that isn't the only record it holds. At almost exactly 17 minutes, it is also the longest musical number in film history, and you can tell. It's self-evidently modeled on "La Carioca" from Flying Down to Rio (which was nominated for the same Oscar!): named after a dance step Fred and Ginger have never tried before, they go and knock one out of the park, a large chorus of dancing extras go through weak sub-Berkeley moves. Only here it's even more trying than in the earlier film, because there's only about 65 seconds of music in "The Continental, which means we hear the song in full some 15 times. The plot is largely resolved at this point, which means that you can enjoy the leads for 3 minutes, leave when the chorus arrives and vacuum or make a small meal or whathaveyou. This is the glory of DVD.

It's not the most satisfying thing in light of what's to come, but it gets the job done. And there is one truly amazing dance to be witnessed. So what if it's not a masterpiece? It's better than the nothing at all we would have if this film hadn't been made.

Day and night, why is it so,

That this longing for you follows wherever I go?

In the roaring traffic's boom,

In the silence of my lonely room,

I think of you, night and day.

To begin, its plot: Fred plays Guy Holden, a famous American dancer who meets Ginger's Mimi Glossop by accident on a London dock where he is awkward and jackassy, she is frigid, he stalks her, he dances with her one time and it's so insanely beautiful that she falls in love on the spot. This plot will recur in...all of them? Absent the character names, and the London docks.

The micro-plot is taken from Gay Divorce, a Cole Porter musical which Astaire starred in on Broadway (the Hays office demanded the title change, although the bawdy double-entendres of the book were let alone; such freedom would not long remain a part of the Astaire & Rogers canon). Mimi is married, as it turns out, and she hires English lawyer Egbert Fitzgerald (Edward Everett Horton, in his first of three films with the duo) to help her arrange a fake liaison so that she can be divorced on the grounds of adultery. Tragically, she never meets the co-respondent Egbert arranges for, Rodolfo Tonetti (Erik Rhodes of the stage version; he would bring the same deeply unprogressive Italian caricature to Top Hat), and believes that Guy has been assigned to the case. She invites him to her room, where innuendos and hijinks ensue.

From the start, Fred and Ginger had unmistakable chemistry onscreen, and although her wise-ass persona had been tamed from the previous year, Ginger was still at heart a comedienne. Which goes a long way to explain, despite a farcical plot that shows every one of its seams, The Gay Divorcee works completely as a comedy. It doesn't hurt that the supporting cast includes three great comic character actors: Horton, of course, as well as Alice Brady playing Ginger's scatterbrained aunt and Eric Blore (his second of five trips with the duo, given infinitely more to do than in Flying Down to Rio) as a bothersome waiter. Everyone fires on all cylinders, there's some genuinely great dialogue, so who cares if the resolution can be spotted as soon as the credits stop rolling? As overseen by the unjustly forgotten, prematurely deceased director Mark Sandrich (another first! He'd go on to direct four more films for the team), it's actually a really high-caliber pre-screwball comedy, and one of a very small number of Astaire-Rogers films that would work almost as well if the songs were taken out entirely.

Of course, part of that has to do with the generally low-quality of the numbers. The film has scuttled almost all of the original Cole Porter soundtrack in favor of songs by Harry Revel & Mack Gordon and Con Conrad & Herb Magidson, and this qualifies as a trade-down. Cole Porter to most people would qualify as a trade-down, of course, but his one included song, "Night and Day," sticks out like a sore thumb. More on that shortly.

The first number, "Don't Let It Bother You," opens things off well enough; a chorus of Parisian (cough) girls singing with some really strange choreography involving doing the can-can with their hands, clad in dolls' clothes. The payoff is when a doll-hand does a bit of jazz hoofing and we find - surprise! - it belongs to Astaire. And then a ridiculous plot contrivance that I do not wish to share brings Fred to the dance floor, where he knocks out a bit of jazzy tapping. It's well-done (it's Fred Astaire), but it's perfunctory and has a distinctly pornographic feeling, like it was just shoved in because that's what we want to see.

Still, it's better than the second and third dances. "A Needle in a Haystack" involves Fred...dressing to music. Yeah. It might be the most pointless solo number in all of his RKO films, and the awful song doesn't help. Moving along: "Let's K-nock K-neez" is something of a novelty song, in that it is performed not by Astaire, nor by Rogers, but by Edward Everett Horton. Wearing a black wife-beater, tiny shorts, and sandals with socks. If you are not intimately familiar with 1930s comedies and do not know off hand what he looks like, it is beyond horror. Images are hard to find on the internet, and for good reason, and I do not intend to contribute one. Also, his singing voice is bad. For no reason other than she was a contracted ingenue, Betty Grable duets with Horton. It's so surreal, I can't even tell you.

And then, there's "Night and Day." It has been said that if Astaire and Rogers never performed another dance together, their place in film history would have been cemented with this song. I'm in no mood to disagree. It's another first for the series, and a much more important one: this is the first major dance to fulfill Fred's desire that no dance be mere spectacle, but instead forward the plot and character development of the film. Boy, does it ever. Mimi goes into the dance hating Guy and just trying not to make a scene, and at the end of it, she's in love. What's amazing about this number, compared to everything else in Hollywood at the time, is how well it's acted (this, I think, goes to the heart of why Ginger was Fred's greatest partner). Look at Rogers' stiffness, her to-this-point reasonable fear of Guy. Look at Astaire's desperate need to hold her close. This is right up with "Cheek to Cheek" and "Never Gonna Dance" as one of their greatest collaborations.

Unfortunately, there's one more song to come, and while it is Fred and Ginger again, it's also every damn day player at RKO. The dance is to the first-ever winner of the Best Song Oscar, "The Continental," but that isn't the only record it holds. At almost exactly 17 minutes, it is also the longest musical number in film history, and you can tell. It's self-evidently modeled on "La Carioca" from Flying Down to Rio (which was nominated for the same Oscar!): named after a dance step Fred and Ginger have never tried before, they go and knock one out of the park, a large chorus of dancing extras go through weak sub-Berkeley moves. Only here it's even more trying than in the earlier film, because there's only about 65 seconds of music in "The Continental, which means we hear the song in full some 15 times. The plot is largely resolved at this point, which means that you can enjoy the leads for 3 minutes, leave when the chorus arrives and vacuum or make a small meal or whathaveyou. This is the glory of DVD.

It's not the most satisfying thing in light of what's to come, but it gets the job done. And there is one truly amazing dance to be witnessed. So what if it's not a masterpiece? It's better than the nothing at all we would have if this film hadn't been made.

Day and night, why is it so,

That this longing for you follows wherever I go?

In the roaring traffic's boom,

In the silence of my lonely room,

I think of you, night and day.

Categories: farce, fred and ginger, hollywood in the 30s, love stories, musicals