The 42nd Chicago International Film Festival

In the beginning: a bird's eye view of marshland. Ancient, untouched swamp - preparing us for an Epic Myth, it seems, and this is confirmed by the first words of the Storyteller (David Gulpilil): "Once upon a time, in a land far, far away..." And then, the Storyteller starts to laugh at his own profundity, and deflate the heightened air as the camera drops down to earth: "I'm only joking."

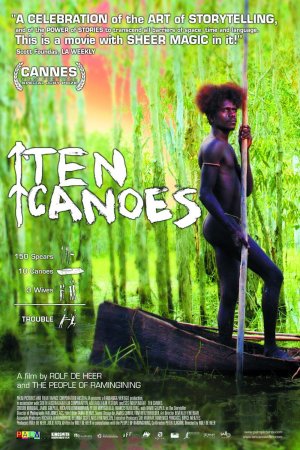

Ten Canoes is a simple story about tiny moments in the life of an Aboriginal Australian tribe in Arnhem Land. There is nothing important or exotic about the film, to its great benefit: it comes across as something of an ethnography, insofar as it treats on the daily life of an isolated community, but it does not insist on their Otherness, nor does it ramble on about how "we're all the same." It simply presents a naturalistic story and lets us draw our own conclusions.

A long time ago, so the Storyteller informs us, a group of hunters travel into the swamp to find goose eggs. They are led by their chief, Minygululu (Peter Minygululu) who is taking his young brother Dayindi (Jamie Gulpilil) into the swamp for the first time. In beautiful black & white photography, we see them stripping bark and fashioning canoes according to an ancient process. The hunters behave as blue collar men do, farting and joking about women, and it comes out that Dayindi is in love with Minygululu's youngest wife. So Minygululu begins a story that will take the entire length of the hunt to complete, for Dayindi's betterment.

Even longer ago, there was a chief named Ridjimariril (Crusoe Kurddal), who had three wives, and a brother Yeeralparil (Jamie Gulpilil again) who covets the youngest. But the story is not just a parallel for the frame narrative; it is an aimless fable that touches on the proper behavior due towards a stranger, the etiquette of warfare, the respect to do other's property. The two narrative threads intertwine throughout the film, appropriate for a culture whose history and identity are so deeply connected to their storytelling traditions.

The story-within-the-story is filmed in full color, partially for the pragmatic reason that it makes it easier to track which story we are viewing at any moment, but mostly for a much richer thematic purpose: if the recent history of Australian native people is depicted largely through black & white photographs (some of which are visually quoted here, including one that gives the film its title), then a story set in that time ought to be in black & white - that is how both the Aboriginals and the outside world view that period. But the ancient story is a myth, and deserves gilding, not unlike Hollywood's persistent attempts to make films look "wow"-er (the film, not incidentally, is shot in 2.35:1 anamorphic widescreen).

In all ways, director Rolf de Heer and cinemtographer Ian Jones have put together an exceptionally well framed film. There is a constant sense of depth: the actors are only one plane in a deep vista, and we are always aware of the space around the action, in front of and behind. This is appropriate, given the stress that the native culture puts on the animism of nature. The forests and swamps aren't merely a setting, they are characters. This is echoed in the constant camera movement, which stresses the physicality of the space by moving around trees and rocks, unable to deny their place in the sceme of things. Because they are "in the way," we must be aware of them; they are proof that life is about more than the mere details of the stories being told.

Because the film only depicts a handful of events that are not extraordinary so much as they are novel, it presents the Aboriginal life not as a documentary object, but a simple and normal thing. This is refreshing, and speaks to the respect de Heer has for this culture. Unfortunately, the ending loses this a bit, and we are shown a funerary rite in exacting detail, with the Storyteller's narration helpfully explaining what everything means: the film abruptly turns into a Discovery Channel special, albeit an unusually pretty one. It is as much an issue of tone as anything: the sequences in the "middle past," based on ethnographic photography, are much drier and more expository, because they represent a time when Aboriginals were depicted only as objects of study. But the ancient story is not for whites, and has been told with a great deal of humor and humanity, and at the very end, this is ignored, although the final shot of this narrative thread makes an attempt to recapture it.

Still, one misstep in a film this brilliant is easy to forgive. Ten Canoes succeeds on the level of mixing the anthropological with the dramatic, and for this alone it is worthy of respect; it is because of the depth of its humanity in telling its stories that it is worthy of love.

9/10

Ten Canoes is a simple story about tiny moments in the life of an Aboriginal Australian tribe in Arnhem Land. There is nothing important or exotic about the film, to its great benefit: it comes across as something of an ethnography, insofar as it treats on the daily life of an isolated community, but it does not insist on their Otherness, nor does it ramble on about how "we're all the same." It simply presents a naturalistic story and lets us draw our own conclusions.

A long time ago, so the Storyteller informs us, a group of hunters travel into the swamp to find goose eggs. They are led by their chief, Minygululu (Peter Minygululu) who is taking his young brother Dayindi (Jamie Gulpilil) into the swamp for the first time. In beautiful black & white photography, we see them stripping bark and fashioning canoes according to an ancient process. The hunters behave as blue collar men do, farting and joking about women, and it comes out that Dayindi is in love with Minygululu's youngest wife. So Minygululu begins a story that will take the entire length of the hunt to complete, for Dayindi's betterment.

Even longer ago, there was a chief named Ridjimariril (Crusoe Kurddal), who had three wives, and a brother Yeeralparil (Jamie Gulpilil again) who covets the youngest. But the story is not just a parallel for the frame narrative; it is an aimless fable that touches on the proper behavior due towards a stranger, the etiquette of warfare, the respect to do other's property. The two narrative threads intertwine throughout the film, appropriate for a culture whose history and identity are so deeply connected to their storytelling traditions.

The story-within-the-story is filmed in full color, partially for the pragmatic reason that it makes it easier to track which story we are viewing at any moment, but mostly for a much richer thematic purpose: if the recent history of Australian native people is depicted largely through black & white photographs (some of which are visually quoted here, including one that gives the film its title), then a story set in that time ought to be in black & white - that is how both the Aboriginals and the outside world view that period. But the ancient story is a myth, and deserves gilding, not unlike Hollywood's persistent attempts to make films look "wow"-er (the film, not incidentally, is shot in 2.35:1 anamorphic widescreen).

In all ways, director Rolf de Heer and cinemtographer Ian Jones have put together an exceptionally well framed film. There is a constant sense of depth: the actors are only one plane in a deep vista, and we are always aware of the space around the action, in front of and behind. This is appropriate, given the stress that the native culture puts on the animism of nature. The forests and swamps aren't merely a setting, they are characters. This is echoed in the constant camera movement, which stresses the physicality of the space by moving around trees and rocks, unable to deny their place in the sceme of things. Because they are "in the way," we must be aware of them; they are proof that life is about more than the mere details of the stories being told.

Because the film only depicts a handful of events that are not extraordinary so much as they are novel, it presents the Aboriginal life not as a documentary object, but a simple and normal thing. This is refreshing, and speaks to the respect de Heer has for this culture. Unfortunately, the ending loses this a bit, and we are shown a funerary rite in exacting detail, with the Storyteller's narration helpfully explaining what everything means: the film abruptly turns into a Discovery Channel special, albeit an unusually pretty one. It is as much an issue of tone as anything: the sequences in the "middle past," based on ethnographic photography, are much drier and more expository, because they represent a time when Aboriginals were depicted only as objects of study. But the ancient story is not for whites, and has been told with a great deal of humor and humanity, and at the very end, this is ignored, although the final shot of this narrative thread makes an attempt to recapture it.

Still, one misstep in a film this brilliant is easy to forgive. Ten Canoes succeeds on the level of mixing the anthropological with the dramatic, and for this alone it is worthy of respect; it is because of the depth of its humanity in telling its stories that it is worthy of love.

9/10

Categories: ciff, fun with structure, oz/kiwi cinema