Cinematic outkasts

Many a year ago, when I was first readying to watch the notorious Beatles film Magical Mystery Tour, I was given this advice: "just fast-forward between the songs. Don't watch the story. Pretend it's a series of music videos."

I'd be inclined to repeat that advice for anyone thinking about seeing the new Outkast musical Idlewild, although at that point you've only got about twenty minutes of film to deal with and it might just be more satisfying to watch the "Hey Ya" video a few times in a row.

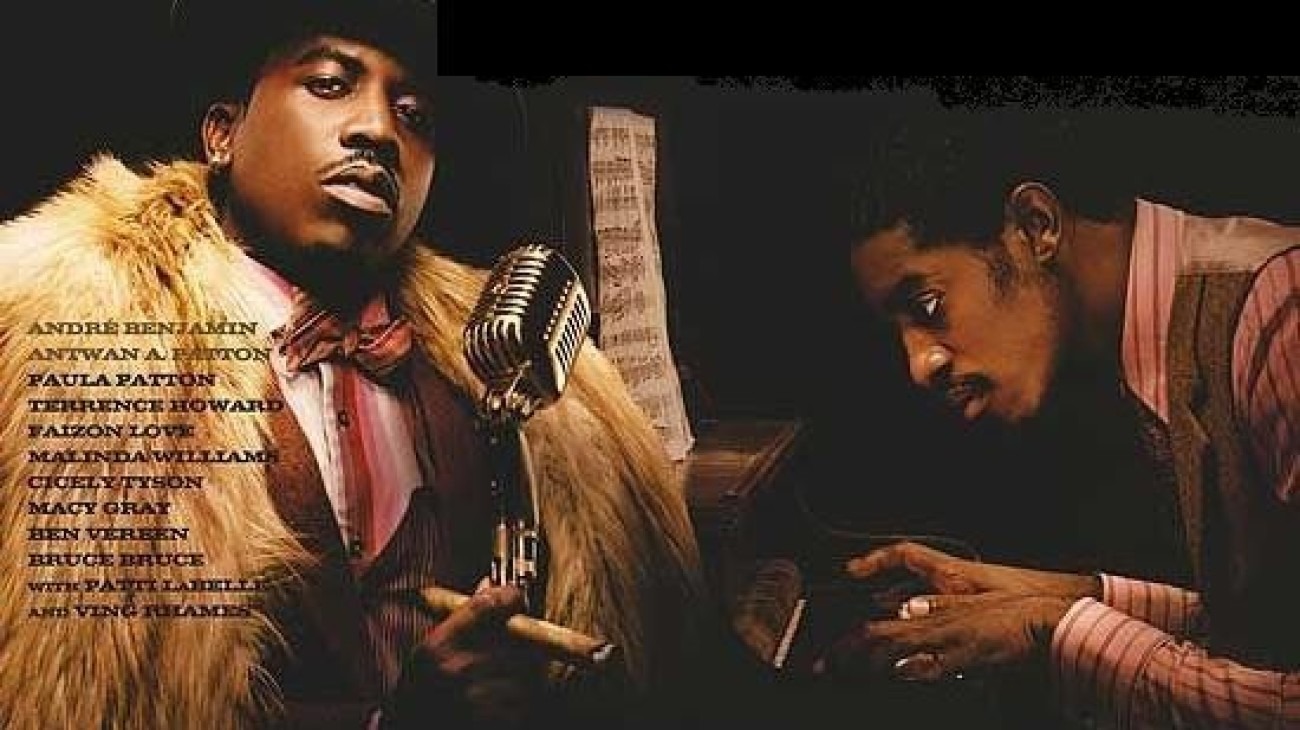

The first danger sign comes during the opening credits. That's inaccurate - in fact, three danger signs come during the credits. The first is the overdone style of the sequence, still photographs popping in and out of 3D, with indivuduals within the photos occasionally winking or smiling or dancing for a few frames. The second is that the sequence, and the narration underneath (the childhood of the two main characters) feels like it drags on for about ten minutes. The third is that André Benjamin and Antwan A. Patton are credited as actors, André 3000 and Big Boi are credited with the the music, and Outkast is never named at all.

This last bit is less of a criticism and more of a metaphor for how badly Idlewild manages the apparently simple task of creating an identity for itself. "An Outkast musical," you hear, and that seems fairly self-explanatory: plot-light, song heavy. Except not - there are precious damn few songs, and not all of those are original.

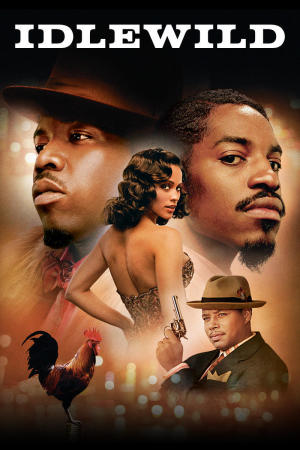

"Okay, so Outkast is branching out," and to judge from the plot of the film, they're reaching for a socially significant drama: Percival (André Benjamin) is a mortician's son and juke joint pianist in the Depression-era Southern town of Idlewild; Rooster (Antwan A. Patton) is a singer and star attraction of that very same joint; they run afould gangsters and bootleggers. There's much commentary on how the poverty-stricken African-American community devours its own, and it's very hard to find anything to respect in any of the characters who aren't Percival.

And that almost might have worked, on paper. Then along comes writer-director Bryan Barber, veteran of the band's music videos, and he has no clue whatsoever how he wants to treat this material. I do not say that because the material is treated indifferently; I say that because in virtually every new scene we find a completely new and usually discordant stylistic idea being thrown at us.

Have you ever seen Moulin Rouge? Well, Bryan Barber certainly has. And for all he talks about the many sources that influenced him - including, absurdly, Vincente Minelli's Cabin in the Sky - it's quite obvious what film inspired every level of Idlewild, from the production design to the choreography to (especially) the editing. Except that Moulin Rouge, for all of its giant excess, was of a piece: each absurdity nestled right in against the next, up until the not-terribly-sad final 90 seconds, which reads almost as a parody of tragedy, so detached is it from the energy of the rest. Idlewild is not of a piece. Idlewild is a film in which a CGI rooster on a flask can scream advice at the driver of a car in a wildly cartoonish chase scene mere seconds after an appalling, brutal murder. Idlewild is a film in which André 3000 sings to a chorus of cuckoo clocks and wears not a trace of a smile, apparently believing that to be a black actor expressing happiness sets race relations in America back to the time of Stepin Fetchit.

Weirdly, the problem is not that the film is excessive, but that it is not nearly excessive enough. Baz Luhrmann buried tragedy underneath miles of Elton John songs, cod-Bollywood sets and John Leguizamo as a dwarf, and thus turned a story about a woman's death into a joyous fantasia. Barber does not come nearly close enough to making the craziness in Idlewild overwhelm the sorrow, but there is far too much craziness to ignore, and most of the time I wasn't sure whether I was supposed to laugh or cry. Take the late scene where little animated men on sheet music are burning alive: I don't think it was supposed to be funny, but I wasn't sure how else to react.

This is all a pity, because individually most of the styles work. The dance numbers in particular rival anything I've seen recently, as well they might under the choreography of Hinton Battle. And for all I complain about CGI roosters and animated sheet-music men, when they're not grotesquely out of place, they're cute ideas. And although I suppose this sounds like faint praise Pascal Rabaud's cinematography is extremely proficient, by which I mean to say that it took a great deal of skill to make things look as they do, and several of the shots are quite gorgeous to look at. And I suppose "proficient" is as much as one could hope for under the guidance of a ringmaster like Barber.

The actors are an entirely mixed bag. Benjman and Patton do fine, although unspectacular work; still it's better than many singers have done in the past (for example). It doesn't help them at all that the villain of the film is the always-fantastic Terrence Howard, or that most of Benjamin's dramatic scenes are against a powerhouse like Ben Vereen. It does help that the romantic lead is the absolutely dreadful Paula Patton (no relation), one of the most uncharismatic and unconvincing chanteuses I've seen in ages. It's hard not to agree with the assessment made by another character that she is shallow and untalented, especially when that character is played by Macy Gray, whose hair has more personality than Ms. Patton's entire performance. (Strangely (significantly?) she is also the "whitest" looking of the cast, but I lack the authority to comment on the sociology of that fact).

A defense of the film could probably be mounted along these lines: it refuses to conform to a simple program of what Should Be and what Is Done, and even that it is a latter-day Nouvelle Vague type of film, so in love with its own cinema-ness as to render considerations of how genre "ought to" work pointless, and indeed to stand as antagonist to any preconceived rules. And while it's possible respect someone for name-dropping the Nouvelle Vague in a conversation about this schizophrenic mess, it's really quite hard to agree with that position: pure and simple, this is an example of the worst kind of directorial overreach and lack of discipline. Nothing fits together. Take your pick: it's a joyless musical or a silly gangster drama. Either way it's a misfire.

4/10

I'd be inclined to repeat that advice for anyone thinking about seeing the new Outkast musical Idlewild, although at that point you've only got about twenty minutes of film to deal with and it might just be more satisfying to watch the "Hey Ya" video a few times in a row.

The first danger sign comes during the opening credits. That's inaccurate - in fact, three danger signs come during the credits. The first is the overdone style of the sequence, still photographs popping in and out of 3D, with indivuduals within the photos occasionally winking or smiling or dancing for a few frames. The second is that the sequence, and the narration underneath (the childhood of the two main characters) feels like it drags on for about ten minutes. The third is that André Benjamin and Antwan A. Patton are credited as actors, André 3000 and Big Boi are credited with the the music, and Outkast is never named at all.

This last bit is less of a criticism and more of a metaphor for how badly Idlewild manages the apparently simple task of creating an identity for itself. "An Outkast musical," you hear, and that seems fairly self-explanatory: plot-light, song heavy. Except not - there are precious damn few songs, and not all of those are original.

"Okay, so Outkast is branching out," and to judge from the plot of the film, they're reaching for a socially significant drama: Percival (André Benjamin) is a mortician's son and juke joint pianist in the Depression-era Southern town of Idlewild; Rooster (Antwan A. Patton) is a singer and star attraction of that very same joint; they run afould gangsters and bootleggers. There's much commentary on how the poverty-stricken African-American community devours its own, and it's very hard to find anything to respect in any of the characters who aren't Percival.

And that almost might have worked, on paper. Then along comes writer-director Bryan Barber, veteran of the band's music videos, and he has no clue whatsoever how he wants to treat this material. I do not say that because the material is treated indifferently; I say that because in virtually every new scene we find a completely new and usually discordant stylistic idea being thrown at us.

Have you ever seen Moulin Rouge? Well, Bryan Barber certainly has. And for all he talks about the many sources that influenced him - including, absurdly, Vincente Minelli's Cabin in the Sky - it's quite obvious what film inspired every level of Idlewild, from the production design to the choreography to (especially) the editing. Except that Moulin Rouge, for all of its giant excess, was of a piece: each absurdity nestled right in against the next, up until the not-terribly-sad final 90 seconds, which reads almost as a parody of tragedy, so detached is it from the energy of the rest. Idlewild is not of a piece. Idlewild is a film in which a CGI rooster on a flask can scream advice at the driver of a car in a wildly cartoonish chase scene mere seconds after an appalling, brutal murder. Idlewild is a film in which André 3000 sings to a chorus of cuckoo clocks and wears not a trace of a smile, apparently believing that to be a black actor expressing happiness sets race relations in America back to the time of Stepin Fetchit.

Weirdly, the problem is not that the film is excessive, but that it is not nearly excessive enough. Baz Luhrmann buried tragedy underneath miles of Elton John songs, cod-Bollywood sets and John Leguizamo as a dwarf, and thus turned a story about a woman's death into a joyous fantasia. Barber does not come nearly close enough to making the craziness in Idlewild overwhelm the sorrow, but there is far too much craziness to ignore, and most of the time I wasn't sure whether I was supposed to laugh or cry. Take the late scene where little animated men on sheet music are burning alive: I don't think it was supposed to be funny, but I wasn't sure how else to react.

This is all a pity, because individually most of the styles work. The dance numbers in particular rival anything I've seen recently, as well they might under the choreography of Hinton Battle. And for all I complain about CGI roosters and animated sheet-music men, when they're not grotesquely out of place, they're cute ideas. And although I suppose this sounds like faint praise Pascal Rabaud's cinematography is extremely proficient, by which I mean to say that it took a great deal of skill to make things look as they do, and several of the shots are quite gorgeous to look at. And I suppose "proficient" is as much as one could hope for under the guidance of a ringmaster like Barber.

The actors are an entirely mixed bag. Benjman and Patton do fine, although unspectacular work; still it's better than many singers have done in the past (for example). It doesn't help them at all that the villain of the film is the always-fantastic Terrence Howard, or that most of Benjamin's dramatic scenes are against a powerhouse like Ben Vereen. It does help that the romantic lead is the absolutely dreadful Paula Patton (no relation), one of the most uncharismatic and unconvincing chanteuses I've seen in ages. It's hard not to agree with the assessment made by another character that she is shallow and untalented, especially when that character is played by Macy Gray, whose hair has more personality than Ms. Patton's entire performance. (Strangely (significantly?) she is also the "whitest" looking of the cast, but I lack the authority to comment on the sociology of that fact).

A defense of the film could probably be mounted along these lines: it refuses to conform to a simple program of what Should Be and what Is Done, and even that it is a latter-day Nouvelle Vague type of film, so in love with its own cinema-ness as to render considerations of how genre "ought to" work pointless, and indeed to stand as antagonist to any preconceived rules. And while it's possible respect someone for name-dropping the Nouvelle Vague in a conversation about this schizophrenic mess, it's really quite hard to agree with that position: pure and simple, this is an example of the worst kind of directorial overreach and lack of discipline. Nothing fits together. Take your pick: it's a joyless musical or a silly gangster drama. Either way it's a misfire.

4/10

Categories: music videos, musicals