What won't they give an Oscar to these days?

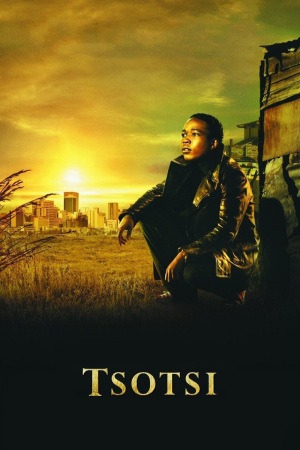

Perhaps none of what I'm about to write will remain true. My thinking in the last twelve hours has flipped a little bit; for a few hours after walking out of Tsotsi, the South African winner of the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, I was prepared to say it more or less worked in spite of its considerable flaws; now I wonder if it doesn't fail in spite of its considerable successes.

I will start out by saying something nice: Presley Chweneyagae, who plays the titular character, is very good in his film debut. He has to make the arc of a young criminal who finds redemption believable, and he succeeds. You can see it in his face and in his posture, that this character is slowly learning how to be honest and open and moral.

I am not sure the screenplay can back him up, though. The story concerns a young man (his nickname Tsotsi is slang for "thug"; his real name is revealed so early and so anticlimactically that I'm not sure why the film makes an issue of it, but there we have it) who jacks a car and shoots its owner, only to find her baby in the back seat. He is not so cold-blooded as to abandon an infant, and he finds himself taking care of it in between flashbacks that make it clear that the reason he's so screwed up is because his own father was a prick.

We've all seen plenty of redemption stories, and they practically write themselves. The problem here is that Tsotsi hasn't - it relies on the audience making a few too many connections. For one, it's not at all clear how Tsotsi's redemption works: the last few minutes of the film are ambiguous in a bad way (I simply don't know what he would have done if the guns weren't there), and throughout, every "redemptive" action he takes can be read on a surface level as trying to do right by the baby, something he clearly commits to early on. So if there is a redemption there, it takes place at the end of the first act and the rest is all gravy (yes, yes, I know, there's the contrast in how he treats his friend Boston in the opening and middle of the film, but other than that I cannot name one "redemptive" act he performs). Also, the "Tsotsi's father sucked" angle seems pitched entirely at the audience, not the characters, and it never seems to tie back to Tsotsi's actions. Its only real effect is to soften Tsotsi's villainy - "oh, he was unloved, poor thing" - and cheapen the redemptive arc.

The other thing that really got to me was the cinematography. Every shot of the film is absolutely perfect and gorgeous - you could mount any given frame on your wall - and I give the film a great deal of credit for that. But I'm not convinced that the cinematography and the script exist in the same place. Most of the images play with a fairly conventional "dark is bad/light is good" motif, with lots of shots of Tsotsi's silhouette blocking out the light, Tsotsi stepping into the light, etc. The problem is that these shots are only csually related to the chronology of Tsotsi's redemption. Much like the script asking the audience to jump from Tsotsi's father issues to his adopting the baby, and from the baby to his redemption, the cinematography makes the audience do most of the work - we know what this visual language means in other films, so let's assume this film does the same things.

A shame, because what it does well it does very well indeed - the performances, the depiction of daily life in Johannesburg, and particularly relating the indoors and the outdoors (outdoors is violent but emotional, indoors is peaceful but constricting) to Tsotsi's development.

I will start out by saying something nice: Presley Chweneyagae, who plays the titular character, is very good in his film debut. He has to make the arc of a young criminal who finds redemption believable, and he succeeds. You can see it in his face and in his posture, that this character is slowly learning how to be honest and open and moral.

I am not sure the screenplay can back him up, though. The story concerns a young man (his nickname Tsotsi is slang for "thug"; his real name is revealed so early and so anticlimactically that I'm not sure why the film makes an issue of it, but there we have it) who jacks a car and shoots its owner, only to find her baby in the back seat. He is not so cold-blooded as to abandon an infant, and he finds himself taking care of it in between flashbacks that make it clear that the reason he's so screwed up is because his own father was a prick.

We've all seen plenty of redemption stories, and they practically write themselves. The problem here is that Tsotsi hasn't - it relies on the audience making a few too many connections. For one, it's not at all clear how Tsotsi's redemption works: the last few minutes of the film are ambiguous in a bad way (I simply don't know what he would have done if the guns weren't there), and throughout, every "redemptive" action he takes can be read on a surface level as trying to do right by the baby, something he clearly commits to early on. So if there is a redemption there, it takes place at the end of the first act and the rest is all gravy (yes, yes, I know, there's the contrast in how he treats his friend Boston in the opening and middle of the film, but other than that I cannot name one "redemptive" act he performs). Also, the "Tsotsi's father sucked" angle seems pitched entirely at the audience, not the characters, and it never seems to tie back to Tsotsi's actions. Its only real effect is to soften Tsotsi's villainy - "oh, he was unloved, poor thing" - and cheapen the redemptive arc.

The other thing that really got to me was the cinematography. Every shot of the film is absolutely perfect and gorgeous - you could mount any given frame on your wall - and I give the film a great deal of credit for that. But I'm not convinced that the cinematography and the script exist in the same place. Most of the images play with a fairly conventional "dark is bad/light is good" motif, with lots of shots of Tsotsi's silhouette blocking out the light, Tsotsi stepping into the light, etc. The problem is that these shots are only csually related to the chronology of Tsotsi's redemption. Much like the script asking the audience to jump from Tsotsi's father issues to his adopting the baby, and from the baby to his redemption, the cinematography makes the audience do most of the work - we know what this visual language means in other films, so let's assume this film does the same things.

A shame, because what it does well it does very well indeed - the performances, the depiction of daily life in Johannesburg, and particularly relating the indoors and the outdoors (outdoors is violent but emotional, indoors is peaceful but constricting) to Tsotsi's development.

Categories: african cinema, joyless mediocrity, warm fuzzies