No, it's not about the bunny.

Return to the complete Twin Peaks index

Written by Mark Frost & David Lynch

Directed by David Lynch

Airdate: 28 May, 2017

Online streaming premiere: 21 May, 2017

Author's Note: This and all subsequent reviews of Twin Peaks: The Return episodes will freely give away details from the episode at hand, and all those preceding it. The spoiler-averse should back away slowly.

With Part 3, I think, Twin Peaks: The Return starts to jell. Part 1 and Part 2 are both wonderful things, but wonderful things that very much feel like they had to announce themselves: the first is a sprawling galaxy of stuff, beautifully atmospheric and confusing and bone-chilling stuff, all happening in pure isolation; the second gives us a roadmap for how the stuff might eventually interact. The are, collectively, David Lynch & Mark Frost's answer to the question, "what does Twin Peaks look like in 2017?" But Part 3 gets to actually start doing something with the array of toys that the first two episodes have laid out for us.

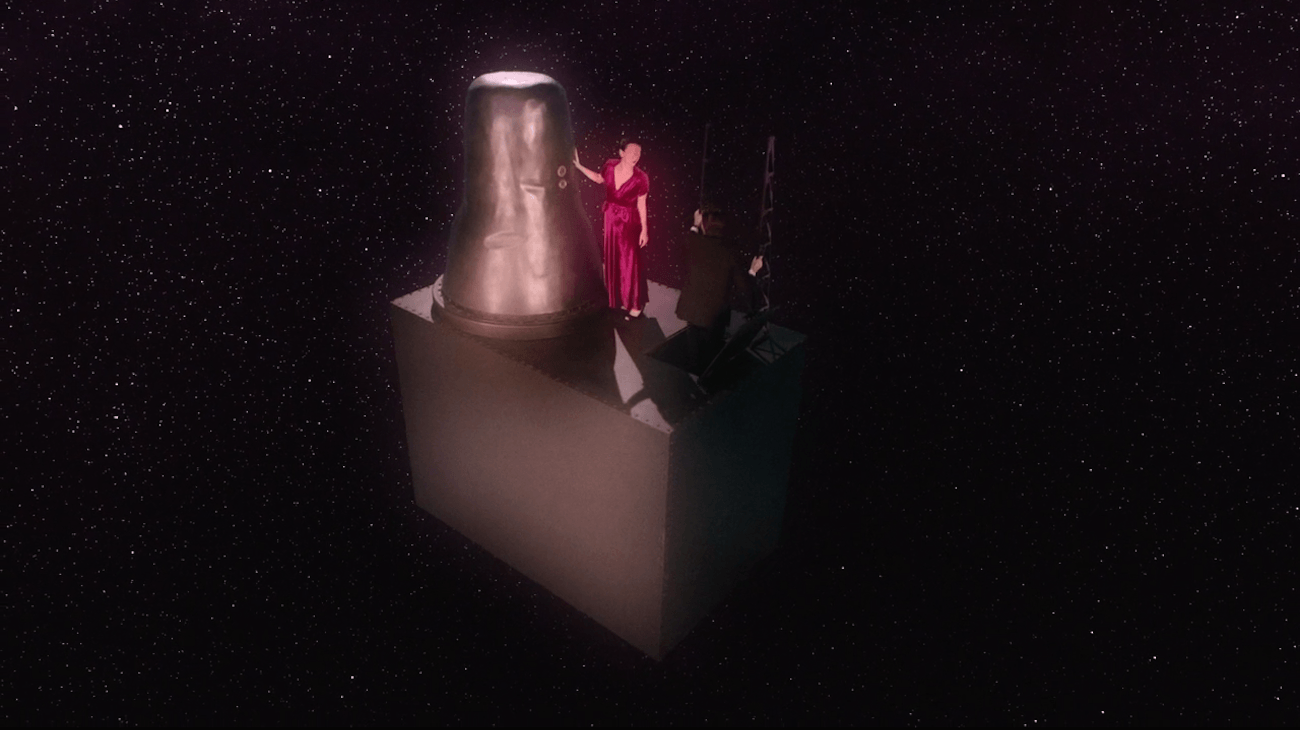

And the main thing it does, for something like 20 or 25 minutes, is to present us with one of the most astounding sequences of Lynch's entire career, in which Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) completes his journey from the Black Lodge, in whatever dimension of reality that might exist, down to the Las Vegas of 2014. I failed to mention, in writing up Part 2, how much I thought of the opening gestures of this journey, which includes a nifty little time loop, and a great one-upping of the Red Room material from Episode 29 at the end of the original run of the show, in a sequence that suggests a dream world starting to break apart at the cusp of waking. But as good as that is, it's not even so much as a practice run for what we get here in Episode 3, which includes some of the most extraordinary filmmaking (if I can use that word, properly speaking) that Lynch has ever employed. It's the closest thing he's ever done as a fully matured artist - which I suppose I mean to describe everything post-Dune - to the mind-melting surrealist shorts of his early career.

It's even closer to what I think we'd get if Lynch and Guy Maddin collaborated on re-making the "beyond the infinite" sequence from 2001: A Space Odyssey. For many the techniques, and to a certain extent the settings, are lifted almost straight from Maddin: the fragmentary cutting, in which we see just frames of a shot that hits the eye like a blast of contrasting light and dark spaces rather than discernible, legible shapes (it helps the connection that this is a largely monochromatic sequence - black and pink, not black and white, but still - like virtually all of Maddin's work), befuddling any possible notion of spatial continuity even without adding in the fact that many of the fragments take place a second or so earlier than the fragment preceding them, so the whole thing moves with a backwards stutter. Augmenting this feeling, the footage that we do get to see for more than a fraction of a sequence is like as not manipulated to speed up and slow down, move forward and move backward, with an erratic, arbitrary rhythm. It is the exact effect you can get if you scrub forward or backward in QuickTime, looking for a specific frame. Actually, it's the exact effect you get if you scrub around in a non-linear editing platform, like Final Cut or Adobe Premiere, which is, I suspect, precisely where the idea came from: watching it, all I could think of was Lynch grabbing the mouse away from editor Duwayne Dunham, scrolling back and forth in increasing aesthetic delight, and ordering "do that!"

The aesthetic object that is the opening of Part 3 is so dumbfounding that I'm almost content to let it stop there, but of course the object is only as good as its affective response, and while I'm quickly getting the impression as I watch it that The Return is as completely subjective as any Lynch project ever has been, I can at least tell you what my response was. Namely, a sense of horrible disorientation and fear (woman with no eyes = creepy. Woman with obvious latex over her eye sockets = somehow creepier, in concert with the blurry cinematography) that becomes soothing and beautiful as it stretches on and on. The 2001 comparison was for a very specific reason: Cooper's voyage feels like the visual expression of a transcendent psycho-spiritual event, one in which the participant is acutely transformed by events that can only be roughly smudged in by the limitations of two-dimensional visual art. I mean, that's a gimme: while certainty about any plot developments in The Return is clearly a fool's game, we are watching the release of Cooper's psychic essence back into the physical realm.

At any rate, by the end of the three-tiered resurrection of Dale Cooper into the body of Dougie Jones (Tier 2 is Evil Cooper vomiting up garmonbozia and black sludge; Tier 3 is that beatifically terrifying wall outlet that sucks up Dougie and spits out Coop), Part 3 had left in me in such a state of blissful weariness that I was going to more or less uncritically applaud anything the show handed me, which is probably why I was so much less put off by Andy (Harry Goaz) and Lucy (Kimmy Robertson) this time compared to their previous appearance; they're still hapless idiots rather than charming small-town naïfs, but Michael Horse's grounding presence as their straight man works better here, and I will not pretend that my nostalgic appreciation for how the whole scene is a long-form riff on "Diane, I am holding in my hand a small box of chocolate bunnies", one of my favorite lines from the pilot.

But honestly, I don't think there's anything else weak enough to require that kind of receptive mood: the long scene of Dr. Jacoby (Russ Tamblyn) patiently spray-painting shovels gold with the help of a homemade hanging rig is the kind of thing apparently put in their with an eye towards testing people's patience - it strongly evokes the shuffling old waiter in Episode 8 - but I think is mostly calming and haunting if you're much on Lynch's wavelength at all (one thing I've noticed about The Return: it is much more clearly the work of a director with a passion for transcendental meditation than anything else he's done; so much of it is slow, go-nowhere moments designed seemingly to do nothing but blank out our minds). And the scene of Gordon Cole (Lynch) and Albert Rosenfield (Miguel Ferrer), though obviously fanservicey, is the good kind of fanservice, echoing with Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me in a way that feels productive rather than simply gratifying, though productive towards what ends, I cannot say.

Plus, I have to salute Lynch as both director and sound designer, and cinematographer Peter Deming for achieving the impossible: placing inside the garishly-lit, chaotically loud space of a Las Vegas casino, and treating it so softly and warmly that it feels downright paradisaical, rather than like the smokey, tacky hellhole it must surely be.

Anyway, I found all of it enjoyable, and much of it challenging, but after the dumb wonderment I take from the opening sequence, my main takeaway is that holy fuck, we are lucky to have the David Lynch/Kyle MacLachlan relationship. I ask sincerely, has MacLachlan ever been good in anything for another director? But he is world-historically great in Twin Peaks, and Part 3 is a bravura showcase of how much range he truly does have. He's playing four different characters in this episode, essentially: Dale Cooper, the shade of a man we once knew, alert and observant but wholly reactive; Evil Cooper, a brutal monster of a human who is struck with mortal fear here, and we need to be able to perceive and understand and sympathise with that fear, while still retaining the knowledge that he is, literally, personified evil; poor Dougie Jones, who we meet only long enough to see his childlike, disappointed surprise at learning that he never existed, and was only "manufactured for a purpose" - that purpose being to absorb the soul of Cooper, of course, but by whom and for what purpose (and, for that matter, which Cooper) will have to be questions for another day; and Cooper-within-Dougie, an automaton slowly grasping for human awareness through rote memorised delivery of words and actions. All four registers are performed impeccably - points to Evil Cooper for highest degree of difficulty, I'd imagine - and it leaves us with a split central performance that greatly humanises and centers the material in a richly-developed character, even if none of the four MacLachlans are necessarily "human" in the strictest sense. And as much as I love the pure, almost abstract emotional affect of the formalism of the opening 20 minutes, having that human anchor is important for tethering that affect to something psychologically relatable.

Grade: A+

Written by Mark Frost & David Lynch

Directed by David Lynch

Airdate: 28 May, 2017

Online streaming premiere: 21 May, 2017

Author's Note: This and all subsequent reviews of Twin Peaks: The Return episodes will freely give away details from the episode at hand, and all those preceding it. The spoiler-averse should back away slowly.

With Part 3, I think, Twin Peaks: The Return starts to jell. Part 1 and Part 2 are both wonderful things, but wonderful things that very much feel like they had to announce themselves: the first is a sprawling galaxy of stuff, beautifully atmospheric and confusing and bone-chilling stuff, all happening in pure isolation; the second gives us a roadmap for how the stuff might eventually interact. The are, collectively, David Lynch & Mark Frost's answer to the question, "what does Twin Peaks look like in 2017?" But Part 3 gets to actually start doing something with the array of toys that the first two episodes have laid out for us.

And the main thing it does, for something like 20 or 25 minutes, is to present us with one of the most astounding sequences of Lynch's entire career, in which Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) completes his journey from the Black Lodge, in whatever dimension of reality that might exist, down to the Las Vegas of 2014. I failed to mention, in writing up Part 2, how much I thought of the opening gestures of this journey, which includes a nifty little time loop, and a great one-upping of the Red Room material from Episode 29 at the end of the original run of the show, in a sequence that suggests a dream world starting to break apart at the cusp of waking. But as good as that is, it's not even so much as a practice run for what we get here in Episode 3, which includes some of the most extraordinary filmmaking (if I can use that word, properly speaking) that Lynch has ever employed. It's the closest thing he's ever done as a fully matured artist - which I suppose I mean to describe everything post-Dune - to the mind-melting surrealist shorts of his early career.

It's even closer to what I think we'd get if Lynch and Guy Maddin collaborated on re-making the "beyond the infinite" sequence from 2001: A Space Odyssey. For many the techniques, and to a certain extent the settings, are lifted almost straight from Maddin: the fragmentary cutting, in which we see just frames of a shot that hits the eye like a blast of contrasting light and dark spaces rather than discernible, legible shapes (it helps the connection that this is a largely monochromatic sequence - black and pink, not black and white, but still - like virtually all of Maddin's work), befuddling any possible notion of spatial continuity even without adding in the fact that many of the fragments take place a second or so earlier than the fragment preceding them, so the whole thing moves with a backwards stutter. Augmenting this feeling, the footage that we do get to see for more than a fraction of a sequence is like as not manipulated to speed up and slow down, move forward and move backward, with an erratic, arbitrary rhythm. It is the exact effect you can get if you scrub forward or backward in QuickTime, looking for a specific frame. Actually, it's the exact effect you get if you scrub around in a non-linear editing platform, like Final Cut or Adobe Premiere, which is, I suspect, precisely where the idea came from: watching it, all I could think of was Lynch grabbing the mouse away from editor Duwayne Dunham, scrolling back and forth in increasing aesthetic delight, and ordering "do that!"

The aesthetic object that is the opening of Part 3 is so dumbfounding that I'm almost content to let it stop there, but of course the object is only as good as its affective response, and while I'm quickly getting the impression as I watch it that The Return is as completely subjective as any Lynch project ever has been, I can at least tell you what my response was. Namely, a sense of horrible disorientation and fear (woman with no eyes = creepy. Woman with obvious latex over her eye sockets = somehow creepier, in concert with the blurry cinematography) that becomes soothing and beautiful as it stretches on and on. The 2001 comparison was for a very specific reason: Cooper's voyage feels like the visual expression of a transcendent psycho-spiritual event, one in which the participant is acutely transformed by events that can only be roughly smudged in by the limitations of two-dimensional visual art. I mean, that's a gimme: while certainty about any plot developments in The Return is clearly a fool's game, we are watching the release of Cooper's psychic essence back into the physical realm.

At any rate, by the end of the three-tiered resurrection of Dale Cooper into the body of Dougie Jones (Tier 2 is Evil Cooper vomiting up garmonbozia and black sludge; Tier 3 is that beatifically terrifying wall outlet that sucks up Dougie and spits out Coop), Part 3 had left in me in such a state of blissful weariness that I was going to more or less uncritically applaud anything the show handed me, which is probably why I was so much less put off by Andy (Harry Goaz) and Lucy (Kimmy Robertson) this time compared to their previous appearance; they're still hapless idiots rather than charming small-town naïfs, but Michael Horse's grounding presence as their straight man works better here, and I will not pretend that my nostalgic appreciation for how the whole scene is a long-form riff on "Diane, I am holding in my hand a small box of chocolate bunnies", one of my favorite lines from the pilot.

But honestly, I don't think there's anything else weak enough to require that kind of receptive mood: the long scene of Dr. Jacoby (Russ Tamblyn) patiently spray-painting shovels gold with the help of a homemade hanging rig is the kind of thing apparently put in their with an eye towards testing people's patience - it strongly evokes the shuffling old waiter in Episode 8 - but I think is mostly calming and haunting if you're much on Lynch's wavelength at all (one thing I've noticed about The Return: it is much more clearly the work of a director with a passion for transcendental meditation than anything else he's done; so much of it is slow, go-nowhere moments designed seemingly to do nothing but blank out our minds). And the scene of Gordon Cole (Lynch) and Albert Rosenfield (Miguel Ferrer), though obviously fanservicey, is the good kind of fanservice, echoing with Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me in a way that feels productive rather than simply gratifying, though productive towards what ends, I cannot say.

Plus, I have to salute Lynch as both director and sound designer, and cinematographer Peter Deming for achieving the impossible: placing inside the garishly-lit, chaotically loud space of a Las Vegas casino, and treating it so softly and warmly that it feels downright paradisaical, rather than like the smokey, tacky hellhole it must surely be.

Anyway, I found all of it enjoyable, and much of it challenging, but after the dumb wonderment I take from the opening sequence, my main takeaway is that holy fuck, we are lucky to have the David Lynch/Kyle MacLachlan relationship. I ask sincerely, has MacLachlan ever been good in anything for another director? But he is world-historically great in Twin Peaks, and Part 3 is a bravura showcase of how much range he truly does have. He's playing four different characters in this episode, essentially: Dale Cooper, the shade of a man we once knew, alert and observant but wholly reactive; Evil Cooper, a brutal monster of a human who is struck with mortal fear here, and we need to be able to perceive and understand and sympathise with that fear, while still retaining the knowledge that he is, literally, personified evil; poor Dougie Jones, who we meet only long enough to see his childlike, disappointed surprise at learning that he never existed, and was only "manufactured for a purpose" - that purpose being to absorb the soul of Cooper, of course, but by whom and for what purpose (and, for that matter, which Cooper) will have to be questions for another day; and Cooper-within-Dougie, an automaton slowly grasping for human awareness through rote memorised delivery of words and actions. All four registers are performed impeccably - points to Evil Cooper for highest degree of difficulty, I'd imagine - and it leaves us with a split central performance that greatly humanises and centers the material in a richly-developed character, even if none of the four MacLachlans are necessarily "human" in the strictest sense. And as much as I love the pure, almost abstract emotional affect of the formalism of the opening 20 minutes, having that human anchor is important for tethering that affect to something psychologically relatable.

Grade: A+

Categories: david lynch, television, twin peaks