Magnetic Poles

No film could possibly earn such a monumental title as Cold War, and at 89 minutes, the new Polish film going by that title (or, anyway, that title in Polish) is hardly monumental besides. But that's okay, it's a masterpiece anyway, the best film yet made by director/co-writer Paweł Pawlikowski. And with his last film being the glorious 2013 character study Ida, being his best took some real doing.

The film spans a decade and a half in the middle of the 20th Century, starting in 1949 in the newly-Communised Poland, where two government musicologists, Wiktor (Tomasz Kot) and Irena (Agata Kulesza) are on a mission to record folk music. The reason for this, we learn soon enough, is that they're attempting to build a national touring company that will bring the traditional music of the good, noble peasantry to all the people of the country. At one stop, they take an audition from a young woman named Zula (Joanna Kulig), whose voice lacks the purity that Irena is looking for, but who makes up for it with sheer presence and personality. Wiktor takes both a professional and a personal interest in Zula, she reciprocates, and from there we're off to the races.

I pretty much mean that literally. Maybe the most singular thing about Cold War is the uncommon speed with which it peels through the years. The film is structured as a series of anecdotes which leap from year to year and city to city. Or perhaps we should favor the music which serves as a backdrop throughout the movie (the song "Two Hearts, Four Eyes", composed by the real-world analogues for Wiktor and Irena, is used in different genres throughout the film to suggest the passage of time and the corruption of Polish folk identity into a prop for authoritarian bureaucrats) and call it a series of verses. Over the course of the fleet running time, Wiktor, never very pleased with the Communists' control over his country, sneaks away into France, while Zula stays behind to hone her skills despite being called upon to sing increasingly hokey, contrived "people's" music written in a mode of Stalinist kitsch. The movie play like something of a condensation of all three Before... movies, as Wiktor and Zula re-encounter each other in various corners of Cold War Europe: Paris, Berlin, Zagreb. Those cities are of course not randomly chosen, with each serving as a symbol for this or that aspect of culture in those days (Paris = Westernised freedom and decadence, as particularly embodied by the jazz club that seems to be the only place the couple goes; Zagreb = an indeterminate space that's both Communist and anti-Soviet*), and the relationship between the two main characters functioning as a duel between different ways of survival (they are modeled after Pawlikowski's own parents, though it is not clear to me how far that extends).

Of course, it also functions as a love story between two people who would be extremely well-advised to get over each other, rather than ruining every moment of their lives trying to idealise a love affair that was more a matter of convenience and proximity to begin with. Like Ida, the film balances character psychology with political history rather nimbly, allowing Zula to be both The Polish Struggle To Find Meaning Under Soviet Rule and also just Zula, a passionate singer who's also a bit surly, prone to making self-destructive choices that also harm the people around her, and gifted with a peerlessly sarcastic sense of humor. Wiktor isn't just The Polish Expatriate Enjoying Freedom While Longing For The Motherland, he's a self-centered moron who can't stop obsessing over a woman much too young for him and wearing his self-pity like a badge. Both actors are absolutely wonderful, particularly, Kulig, who has to cope with the way that the script by Pawlikowski and Janusz Głowacki keeps drifting back to Wiktor's point of view, and manages to make her efforts to grab the film back from her scene partner double as Zula's dogged attempt to retain her personality beneath the weight of government-enforced non-art.

But I mentioned the film's speed. The film rockets through years in minutes, leaving almost more of the skeleton of an international love affair than the actual story of one; it exists as a collection of moments snatched out of time, to be treasured or regretted as need be, offering the suggestion of "what happened" rather than trying to pin it down and preserve it. Maybe we could go so far as to say that Cold War is ultimately about the futility of trying to bring history back to life in the movies; they cannot ever depict the past, they can only indicate it, sketch its outline, or offer a scribbled summary. Or maybe this too can be centered in these characters and this story, enacting in the film's very structure the constant tension and wearying quality of their lives in Cold War Europe, always moving forward and never given the luxury of relaxing and settling in one place and time.

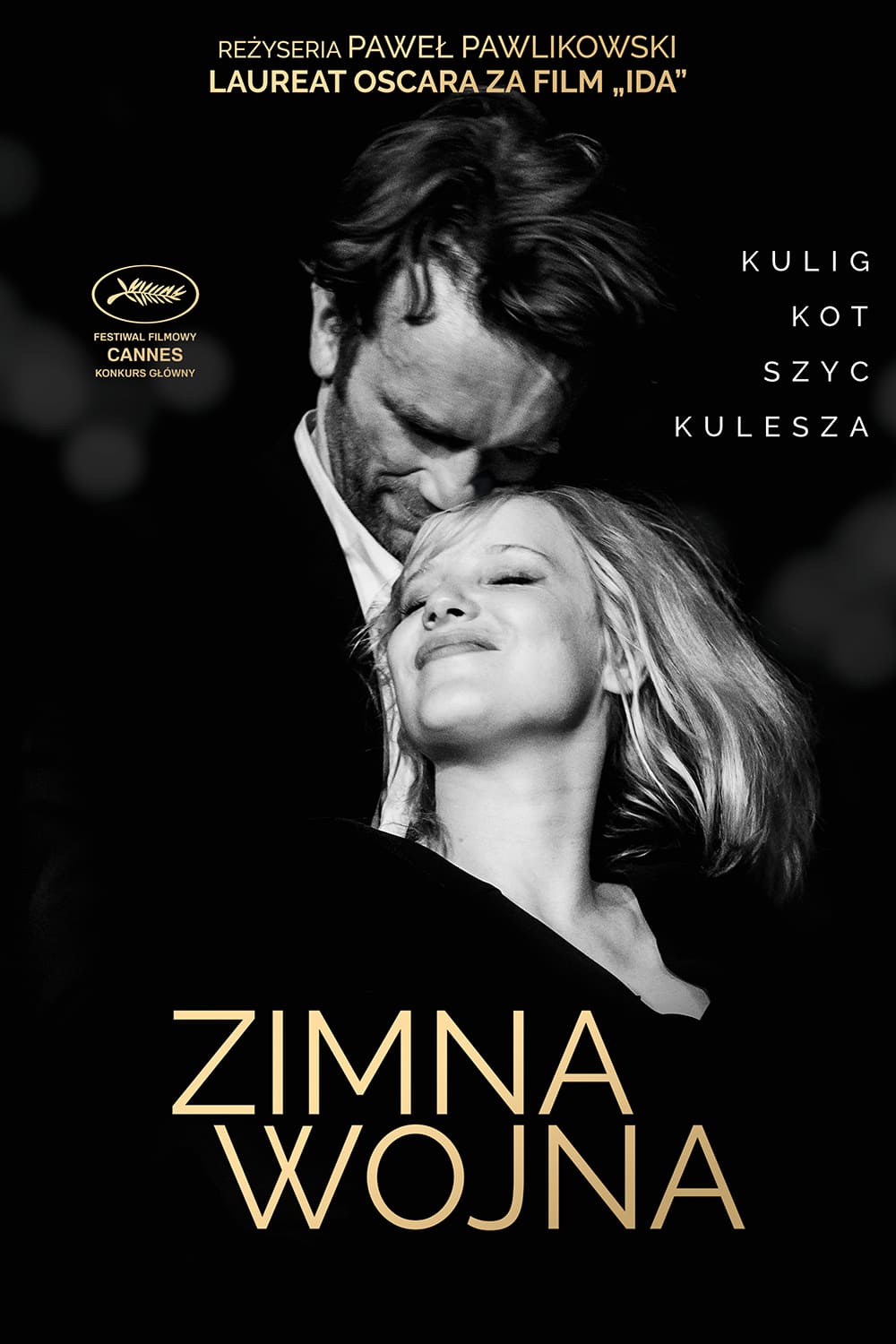

Besides its wonderfully frantic pace, the other most obviously noticeable element of Cold War is its look. As they did with Ida, Pawlikowski and cinematographer Łukasz Żal have used the standard Academy ratio, 1.37:1, to frame their immaculate, glossy black-and-white images. In this case, the square-ish image is being used in a most startling and unconventional way: not to box in the characters, the way it almost always is in contemporary filmmaking, but to exaggerate the openness of the space around them. The film's signature composition is to frame its characters from the chest up, but leave a good two-thirds or more of the frame open above their heads. It's a powerful, albeit kind of trite, use of negative space to represent the forces of culture, politics, and history crushing the characters down; somehow, it's used just sparingly enough that it never loses its impact, but always remains startling and heavy.

The film also makes great use of the ratio in more standard ways, letting the characters' faces fill the screen with their unstated hopes and tensions and sorrows (Kulig is, once again, just the absolute best at this). And sometimes it serves to bind them together in wide shots that center them against the world. Or sometimes, it allows them to leave and have their absence from those wide shots feel like the most solemnly hopeless thing in a world without hope - and thus we get the film's fantastic final shot, the best closing image of 2018 (particularly thanks to a ghostly little puff of wind that I kind of hope was just a happy accident, though it certainly seems intentional). At any rate, the film is exceptionally beautiful, but never just beautiful; the gorgeous images are always tinged with decay, clutter, or emptiness, a perfect visual embodiment of a Europe reeling from the end of a hideous war and torn against itself. The metaphors in Cold War aren't subtle in the least, but they work inordinately well, creating a love story that feels strangled by history, a character study and historical tone poem that triumphs on both of those levels.

*If you don't get the symbolic importance of Cold War-era Berlin, you would be better served by a history book than a movie review.

The film spans a decade and a half in the middle of the 20th Century, starting in 1949 in the newly-Communised Poland, where two government musicologists, Wiktor (Tomasz Kot) and Irena (Agata Kulesza) are on a mission to record folk music. The reason for this, we learn soon enough, is that they're attempting to build a national touring company that will bring the traditional music of the good, noble peasantry to all the people of the country. At one stop, they take an audition from a young woman named Zula (Joanna Kulig), whose voice lacks the purity that Irena is looking for, but who makes up for it with sheer presence and personality. Wiktor takes both a professional and a personal interest in Zula, she reciprocates, and from there we're off to the races.

I pretty much mean that literally. Maybe the most singular thing about Cold War is the uncommon speed with which it peels through the years. The film is structured as a series of anecdotes which leap from year to year and city to city. Or perhaps we should favor the music which serves as a backdrop throughout the movie (the song "Two Hearts, Four Eyes", composed by the real-world analogues for Wiktor and Irena, is used in different genres throughout the film to suggest the passage of time and the corruption of Polish folk identity into a prop for authoritarian bureaucrats) and call it a series of verses. Over the course of the fleet running time, Wiktor, never very pleased with the Communists' control over his country, sneaks away into France, while Zula stays behind to hone her skills despite being called upon to sing increasingly hokey, contrived "people's" music written in a mode of Stalinist kitsch. The movie play like something of a condensation of all three Before... movies, as Wiktor and Zula re-encounter each other in various corners of Cold War Europe: Paris, Berlin, Zagreb. Those cities are of course not randomly chosen, with each serving as a symbol for this or that aspect of culture in those days (Paris = Westernised freedom and decadence, as particularly embodied by the jazz club that seems to be the only place the couple goes; Zagreb = an indeterminate space that's both Communist and anti-Soviet*), and the relationship between the two main characters functioning as a duel between different ways of survival (they are modeled after Pawlikowski's own parents, though it is not clear to me how far that extends).

Of course, it also functions as a love story between two people who would be extremely well-advised to get over each other, rather than ruining every moment of their lives trying to idealise a love affair that was more a matter of convenience and proximity to begin with. Like Ida, the film balances character psychology with political history rather nimbly, allowing Zula to be both The Polish Struggle To Find Meaning Under Soviet Rule and also just Zula, a passionate singer who's also a bit surly, prone to making self-destructive choices that also harm the people around her, and gifted with a peerlessly sarcastic sense of humor. Wiktor isn't just The Polish Expatriate Enjoying Freedom While Longing For The Motherland, he's a self-centered moron who can't stop obsessing over a woman much too young for him and wearing his self-pity like a badge. Both actors are absolutely wonderful, particularly, Kulig, who has to cope with the way that the script by Pawlikowski and Janusz Głowacki keeps drifting back to Wiktor's point of view, and manages to make her efforts to grab the film back from her scene partner double as Zula's dogged attempt to retain her personality beneath the weight of government-enforced non-art.

But I mentioned the film's speed. The film rockets through years in minutes, leaving almost more of the skeleton of an international love affair than the actual story of one; it exists as a collection of moments snatched out of time, to be treasured or regretted as need be, offering the suggestion of "what happened" rather than trying to pin it down and preserve it. Maybe we could go so far as to say that Cold War is ultimately about the futility of trying to bring history back to life in the movies; they cannot ever depict the past, they can only indicate it, sketch its outline, or offer a scribbled summary. Or maybe this too can be centered in these characters and this story, enacting in the film's very structure the constant tension and wearying quality of their lives in Cold War Europe, always moving forward and never given the luxury of relaxing and settling in one place and time.

Besides its wonderfully frantic pace, the other most obviously noticeable element of Cold War is its look. As they did with Ida, Pawlikowski and cinematographer Łukasz Żal have used the standard Academy ratio, 1.37:1, to frame their immaculate, glossy black-and-white images. In this case, the square-ish image is being used in a most startling and unconventional way: not to box in the characters, the way it almost always is in contemporary filmmaking, but to exaggerate the openness of the space around them. The film's signature composition is to frame its characters from the chest up, but leave a good two-thirds or more of the frame open above their heads. It's a powerful, albeit kind of trite, use of negative space to represent the forces of culture, politics, and history crushing the characters down; somehow, it's used just sparingly enough that it never loses its impact, but always remains startling and heavy.

The film also makes great use of the ratio in more standard ways, letting the characters' faces fill the screen with their unstated hopes and tensions and sorrows (Kulig is, once again, just the absolute best at this). And sometimes it serves to bind them together in wide shots that center them against the world. Or sometimes, it allows them to leave and have their absence from those wide shots feel like the most solemnly hopeless thing in a world without hope - and thus we get the film's fantastic final shot, the best closing image of 2018 (particularly thanks to a ghostly little puff of wind that I kind of hope was just a happy accident, though it certainly seems intentional). At any rate, the film is exceptionally beautiful, but never just beautiful; the gorgeous images are always tinged with decay, clutter, or emptiness, a perfect visual embodiment of a Europe reeling from the end of a hideous war and torn against itself. The metaphors in Cold War aren't subtle in the least, but they work inordinately well, creating a love story that feels strangled by history, a character study and historical tone poem that triumphs on both of those levels.

*If you don't get the symbolic importance of Cold War-era Berlin, you would be better served by a history book than a movie review.