Baby mama

A review requested by Paul Royar, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Palindromes isn't merely an example of a kind of film we don't really have any more, it is a film that in some inadvertent way seems to be aware of that fact. The fifth feature written and directed by Todd Solondz opens with a morbid call-back to the second, with a title card announcing "In loving memory of Dawn Wiener". Dawn Wiener being the protagonist of Welcome to the Dollhouse, the film that made Solondz's career when it met with unexpected financial and critical success during its commercial release in the summer of 1996. Those were the salad days of the U.S. indie film industry, the middle and late '90s, and Solondz quickly became one of the major forces of that epoch, between Dollhouse and its in-your-face followup, the legendary, infamous Happiness of 1998.

There's a certain perfect elegance, surely accidental, to Solondz killing of Dawn in 2004, for this was around the time that wave of indie films started its decline. Indie films were still getting made - indie films are still getting made now, almost all the way to the 2020s - but not with the specific force that animated directors like Solondz, Neil LaBute, the early David O. Russell, the good Gus Van Sant, anybody who worked with Killer Films and producer Christine Vachon. This was an era of indie movies that really and truly wanted to set themselves aside from anything and everything mainstream, presenting hard, at times deeply unsettling and upsetting depictions of adult behavior, aggressively taunting and challenging the viewer. In 2004, it felt like it would be around forever, and by the time Solondz made his very next film, Life During Wartime, in 2009, it was at least implicitly advertised and received by critics with a vibe of "hey, remember that Todd Solondz fella? Well, he came back!"

And so: Dawn Wiener dies, and so does what we might well call the Welcome to the Dollhouse era in indie filmmaking. The film that springs from her death - or rather, her awkward, cringe-inducing funeral - is, appropriately, something of a summing-up for all of Solondz's work to that point: the characters of Dollhouse, the extreme content of Happiness, the formal experimentation of Storytelling, from 2001. What we have here is a sort of anti-coming-of-age movie, centered on Dawn's cousin Aviva; concerned, thanks to some ill-advised relative's offhand comment, that she might be on the same path as the suicidal Dawn, Aviva has a heart-to-heart with her mother Joyce (Ellen Barkin). The net result of this conversation is that Aviva commits, with single-minded devotion, to the idea that she wants most of all to be the mother to a whole lot of babies. And this is why, when she's around 13 years old, she deliberately has unprotected sex with Judah (Robert Agri), the inarticulate son of some family friends. She does get pregnant, sending Joyce and father Steve (Richard Masur) into frenzy that leads straight to an abortion clinic. The surgery goes wrong, and Dr. Fleischer (Stephen Singer) must perform an emergency hysterectomy to save Aviva's life; the girl doesn't realise this, though, and sets off on a hitchhiking journey to find a place where she can raise her family in peace. Along the way, she meets the sleazy trucker Joe (Stephen Adly Guirgis), falling in love with him after he rapes her; when he flees, she heads down a nearby river until she arrives at the home of the Sunshine Family, where beatific right-wing Christian Mama Sunshine (Debra Monk) takes care of a huge number of children with a variety of disabilities, while she and her husband Bo (Walter Bobbie) plan to murder abortionists.

That's more than enough to demonstrate that Palindromes is more or less entirely constructed out of elements designed to upset pretty much everybody who comes into contact with it, perhaps even more than Happiness was. To be fair, Solondz isn't just gathering offensive material with an intent to shock. He's partially doing that, undoubtedly. Shocking material is his bread and butter, after all, in keeping with the '90s indie film mission to épater some fucking bourgeoisie. But the reason that Solondz is more than just a snot-nosed stone-thrower, for all I've never really cared for him (though I do like Dollhouse quite a bit), is that he's clearly got some ideas to start shoving our way once he knocks us off kilter with things like statutory rape and onscreen sex between 13-year-olds and that most electric of all third rails in American culture, The Abortion Debate. Palindromes really wants us to think about what it presents: the way that 21st Century America shoves children into sexuality whether they're ready for it or not, while simultaneously sanctifying children as innocent doves of the purest snow in the face of all evidence. And while I don't think Solondz is as carefully even-handed as Solondz seems to think he is (we are definitely not invited to think of Mama Sunshine as anything but a kitschy freak, even with Monk's sympathetic, best-in-show performance reinstating some of her humanity), it's still admirable how much Palindromes wants to raise questions for us but let us do all the thinking and answering on our own.

So with that said, I do wish I actually liked the film. There are two reasons I don't, one of which is entirely subjective: I don't think it's funny. Of course, "the film about a botched abortion and child rape isn't funny" is not, on paper, surprising, except that Palindromes is very definitely a comedy, in very much the same vein as every other Solondz film I've seen. He was on the cutting edge of cringe humor in the 1990s, and while it's definitely true that cringe humor had become much more normalised in 2004 than it was in 1995, Palindromes is still some next-level stuff, primarily in the ghastly sexual relationships Aviva experiences with Judah and Joe, and even more so in everything involving the Sunshine Family, a very well-meaning group where everybody excepts everyone else as perfect and good despite their physical limitations, while singing incredibly godawful Christian Rock numbers as part of a hapless all-kid group, and while merrily spewing the most visceral, acidic hate for anybody who's not part of their very narrowly-defined branch of Christianity.

Once upon a time, I found cringe humor at least bold, if not always pleasurable or funny; age has turned me into a mirthless scold, I guess. But it seems sort of... easy? I will confess that the same indie movement of the '90s I just spent so many words sketching out mostly hasn't aged very well for me, except in a sort of nostalgic, "wow, they don't do that any more" register, largely because so many of those filmmakers were so self-consciously "Edgy", which increasingly feels to me more like a pose than a sustainable aesthetic strategy. And nobody was edgier than Solondz, who in Palindromes seems to be at exactly the point where he transitions from "I'm doing this because I need to plumb the depths of humanity for my art" to "I'm doing this because it's my brand". Anyway, as I said, it's all subjective, but I do find this film to be something of a huge bummer to watch; not that it shouldn't be I guess, but even Happiness isn't a "bummer".

The other reason I can't quite cotton to Palindromes has to do with its central aesthetic conceit, so central that it's a bit ridiculous of me to not bring it up till this point. See, the film is divided into nine chapters, each named for the single character (either real or symbolic) who most affects Aviva's life during those days, minutes, or weeks. And in the first eight of those chapters, she is played by a different actor (in the ninth, they all come back for brief moments). This is, first off, a very cool experiment. And second off, it's an experiment that doesn't yield any results. In principle, the most obvious reason to do this kind of thing is to show the process by which a 13-year-old girl finds her identity: she has to try out several different versions of herself in different situations, and then at the end synthesises all of these versions into her one true self. But Palindromes isn't telling that story: Aviva is in fact marked more by her uniform single-mindedness than by her self-doubt. And if that was the reason the film was using this most incredibly showy gimmick, it would make sense to start with the most "neutral" Aviva, the one that the rest of the world sees her as; instead, the Aviva of Chapter 1 ("Dawn") is Emani Sledge, one of two African-American actors playing the explicitly Jewish character.

There's also the problem that, of the eight performers, three (#2, Valerie Shusterov; #4, Rachel Corr; and #7, Shayna Levine) resemble each other so closely that the apparent value of having a different Aviva every time is somewhat lost. And after seven total unknowns, the eighth and final Aviva is played by Jennifer Jason Leigh, easily the most famous person in the cast (my apologies to the Ellen Barkin fans in the house), and other than some indistinct sense that you always save the headliner for last, it's not clear what benefit it is to the film to have Aviva suddenly played by a recognisable actor right at the end. The only time that handing off the role like this actually pays off in a specific, describable way is in Chapter 5, "Huckleberry", the one time that Aviva is played by a male (Will Denton): it's a wordless, dusk-set snapshot of a river voyage, with Aviva drifting along in a plastic kids' boat as Nathan Larson's main theme sings along on the score in a dreamily melancholy way. There's something in there about the way that American mythology views boys going off and having mischievous adventures as marvelous (the chapter title, the only one not repeated in dialogue, is an obvious Mark Twain reference), while girls doing the same is terrifying; it's by no means something the film develops, but it's there.

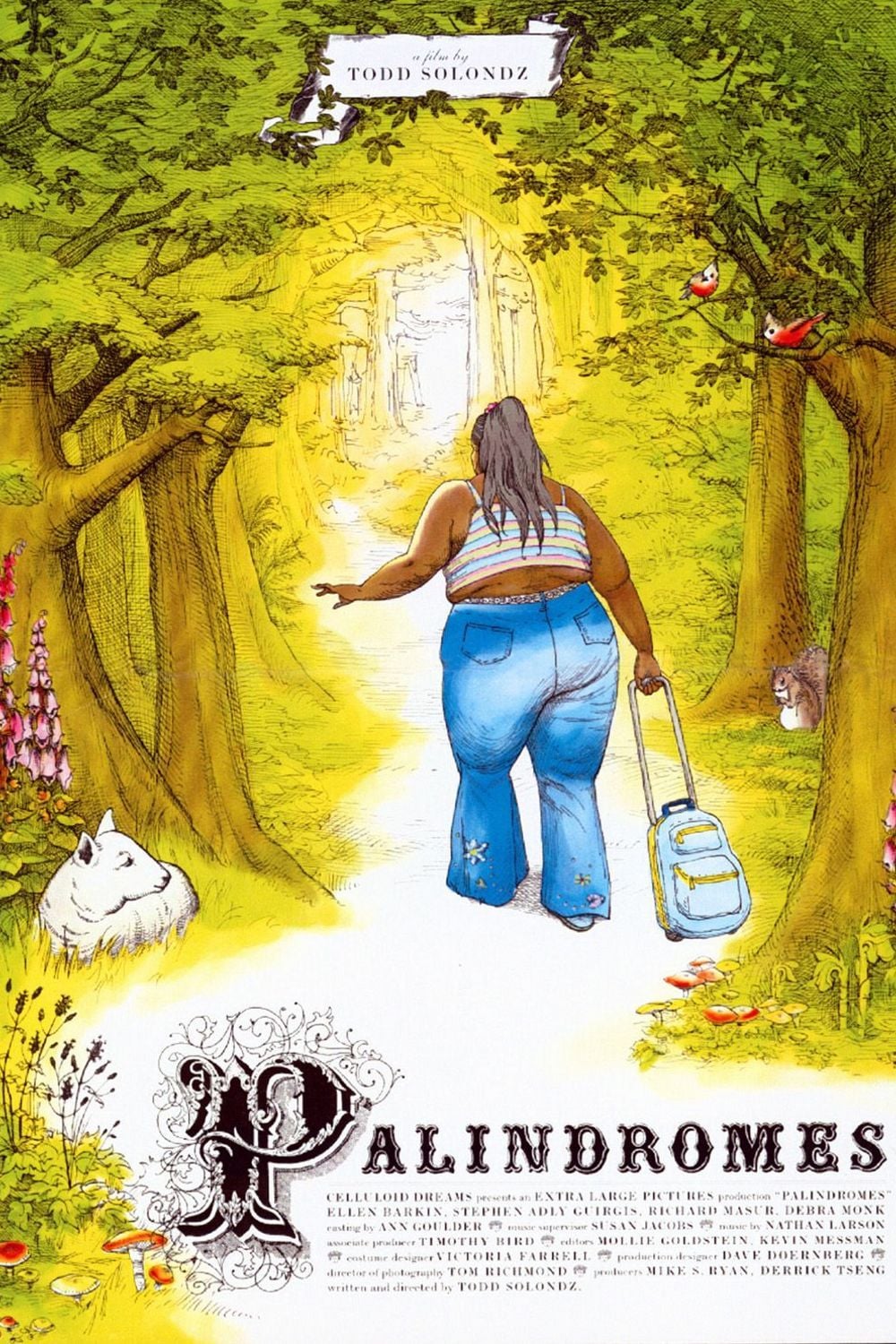

None of this is to say that there aren't pleasures here: all eight of the performances work, quite well. Sledge is adorably ebullient, Shusterov's nervous mumbling is tremendously humane, Hannah Freiman (from Chapter 3) exudes raw, confused terror quite well. Leigh's shy, sad baby of a character is heartbreaking, giving us the sense that Aviva has receded into a protective shell, having grown not at all from her experiences and quite apparently having been damaged by them. The best of the Avivas is Sharon Wilkins, who plays the character in the long, expansive Chapter 6, "Mama Sunshine"; she's physically the outlier of the group, an extremely overweight African-American woman, but she gets the closest to the confused, wary core of the character. She plays a mumbling, nervous runaway surrounded by friendly people who would hate her if they knew the truth about her past so precisely that it becomes quite impossible to remember that she's a fully-grown adult, looming over her castmates, even when you're looking straight at her doing so.

I don't want to give the film too much grief for its central casting conceit, then: it has given us quite a few marvelous performances to enjoy. At the same time, it's so much: this is the kind of huge, Brechtian-style gesture that so completely dominates the movie regardless of everything else within it, that it damn well better be doing something important. And I simply don't see that it is: it seems stuck entirely at the level of "what would happen if we tried..." I doubt that I'd have ever loved Palindromes, but I think I could at least remotely admire it, if not for the way its major central idea leaves it so emotionally distant.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Palindromes isn't merely an example of a kind of film we don't really have any more, it is a film that in some inadvertent way seems to be aware of that fact. The fifth feature written and directed by Todd Solondz opens with a morbid call-back to the second, with a title card announcing "In loving memory of Dawn Wiener". Dawn Wiener being the protagonist of Welcome to the Dollhouse, the film that made Solondz's career when it met with unexpected financial and critical success during its commercial release in the summer of 1996. Those were the salad days of the U.S. indie film industry, the middle and late '90s, and Solondz quickly became one of the major forces of that epoch, between Dollhouse and its in-your-face followup, the legendary, infamous Happiness of 1998.

There's a certain perfect elegance, surely accidental, to Solondz killing of Dawn in 2004, for this was around the time that wave of indie films started its decline. Indie films were still getting made - indie films are still getting made now, almost all the way to the 2020s - but not with the specific force that animated directors like Solondz, Neil LaBute, the early David O. Russell, the good Gus Van Sant, anybody who worked with Killer Films and producer Christine Vachon. This was an era of indie movies that really and truly wanted to set themselves aside from anything and everything mainstream, presenting hard, at times deeply unsettling and upsetting depictions of adult behavior, aggressively taunting and challenging the viewer. In 2004, it felt like it would be around forever, and by the time Solondz made his very next film, Life During Wartime, in 2009, it was at least implicitly advertised and received by critics with a vibe of "hey, remember that Todd Solondz fella? Well, he came back!"

And so: Dawn Wiener dies, and so does what we might well call the Welcome to the Dollhouse era in indie filmmaking. The film that springs from her death - or rather, her awkward, cringe-inducing funeral - is, appropriately, something of a summing-up for all of Solondz's work to that point: the characters of Dollhouse, the extreme content of Happiness, the formal experimentation of Storytelling, from 2001. What we have here is a sort of anti-coming-of-age movie, centered on Dawn's cousin Aviva; concerned, thanks to some ill-advised relative's offhand comment, that she might be on the same path as the suicidal Dawn, Aviva has a heart-to-heart with her mother Joyce (Ellen Barkin). The net result of this conversation is that Aviva commits, with single-minded devotion, to the idea that she wants most of all to be the mother to a whole lot of babies. And this is why, when she's around 13 years old, she deliberately has unprotected sex with Judah (Robert Agri), the inarticulate son of some family friends. She does get pregnant, sending Joyce and father Steve (Richard Masur) into frenzy that leads straight to an abortion clinic. The surgery goes wrong, and Dr. Fleischer (Stephen Singer) must perform an emergency hysterectomy to save Aviva's life; the girl doesn't realise this, though, and sets off on a hitchhiking journey to find a place where she can raise her family in peace. Along the way, she meets the sleazy trucker Joe (Stephen Adly Guirgis), falling in love with him after he rapes her; when he flees, she heads down a nearby river until she arrives at the home of the Sunshine Family, where beatific right-wing Christian Mama Sunshine (Debra Monk) takes care of a huge number of children with a variety of disabilities, while she and her husband Bo (Walter Bobbie) plan to murder abortionists.

That's more than enough to demonstrate that Palindromes is more or less entirely constructed out of elements designed to upset pretty much everybody who comes into contact with it, perhaps even more than Happiness was. To be fair, Solondz isn't just gathering offensive material with an intent to shock. He's partially doing that, undoubtedly. Shocking material is his bread and butter, after all, in keeping with the '90s indie film mission to épater some fucking bourgeoisie. But the reason that Solondz is more than just a snot-nosed stone-thrower, for all I've never really cared for him (though I do like Dollhouse quite a bit), is that he's clearly got some ideas to start shoving our way once he knocks us off kilter with things like statutory rape and onscreen sex between 13-year-olds and that most electric of all third rails in American culture, The Abortion Debate. Palindromes really wants us to think about what it presents: the way that 21st Century America shoves children into sexuality whether they're ready for it or not, while simultaneously sanctifying children as innocent doves of the purest snow in the face of all evidence. And while I don't think Solondz is as carefully even-handed as Solondz seems to think he is (we are definitely not invited to think of Mama Sunshine as anything but a kitschy freak, even with Monk's sympathetic, best-in-show performance reinstating some of her humanity), it's still admirable how much Palindromes wants to raise questions for us but let us do all the thinking and answering on our own.

So with that said, I do wish I actually liked the film. There are two reasons I don't, one of which is entirely subjective: I don't think it's funny. Of course, "the film about a botched abortion and child rape isn't funny" is not, on paper, surprising, except that Palindromes is very definitely a comedy, in very much the same vein as every other Solondz film I've seen. He was on the cutting edge of cringe humor in the 1990s, and while it's definitely true that cringe humor had become much more normalised in 2004 than it was in 1995, Palindromes is still some next-level stuff, primarily in the ghastly sexual relationships Aviva experiences with Judah and Joe, and even more so in everything involving the Sunshine Family, a very well-meaning group where everybody excepts everyone else as perfect and good despite their physical limitations, while singing incredibly godawful Christian Rock numbers as part of a hapless all-kid group, and while merrily spewing the most visceral, acidic hate for anybody who's not part of their very narrowly-defined branch of Christianity.

Once upon a time, I found cringe humor at least bold, if not always pleasurable or funny; age has turned me into a mirthless scold, I guess. But it seems sort of... easy? I will confess that the same indie movement of the '90s I just spent so many words sketching out mostly hasn't aged very well for me, except in a sort of nostalgic, "wow, they don't do that any more" register, largely because so many of those filmmakers were so self-consciously "Edgy", which increasingly feels to me more like a pose than a sustainable aesthetic strategy. And nobody was edgier than Solondz, who in Palindromes seems to be at exactly the point where he transitions from "I'm doing this because I need to plumb the depths of humanity for my art" to "I'm doing this because it's my brand". Anyway, as I said, it's all subjective, but I do find this film to be something of a huge bummer to watch; not that it shouldn't be I guess, but even Happiness isn't a "bummer".

The other reason I can't quite cotton to Palindromes has to do with its central aesthetic conceit, so central that it's a bit ridiculous of me to not bring it up till this point. See, the film is divided into nine chapters, each named for the single character (either real or symbolic) who most affects Aviva's life during those days, minutes, or weeks. And in the first eight of those chapters, she is played by a different actor (in the ninth, they all come back for brief moments). This is, first off, a very cool experiment. And second off, it's an experiment that doesn't yield any results. In principle, the most obvious reason to do this kind of thing is to show the process by which a 13-year-old girl finds her identity: she has to try out several different versions of herself in different situations, and then at the end synthesises all of these versions into her one true self. But Palindromes isn't telling that story: Aviva is in fact marked more by her uniform single-mindedness than by her self-doubt. And if that was the reason the film was using this most incredibly showy gimmick, it would make sense to start with the most "neutral" Aviva, the one that the rest of the world sees her as; instead, the Aviva of Chapter 1 ("Dawn") is Emani Sledge, one of two African-American actors playing the explicitly Jewish character.

There's also the problem that, of the eight performers, three (#2, Valerie Shusterov; #4, Rachel Corr; and #7, Shayna Levine) resemble each other so closely that the apparent value of having a different Aviva every time is somewhat lost. And after seven total unknowns, the eighth and final Aviva is played by Jennifer Jason Leigh, easily the most famous person in the cast (my apologies to the Ellen Barkin fans in the house), and other than some indistinct sense that you always save the headliner for last, it's not clear what benefit it is to the film to have Aviva suddenly played by a recognisable actor right at the end. The only time that handing off the role like this actually pays off in a specific, describable way is in Chapter 5, "Huckleberry", the one time that Aviva is played by a male (Will Denton): it's a wordless, dusk-set snapshot of a river voyage, with Aviva drifting along in a plastic kids' boat as Nathan Larson's main theme sings along on the score in a dreamily melancholy way. There's something in there about the way that American mythology views boys going off and having mischievous adventures as marvelous (the chapter title, the only one not repeated in dialogue, is an obvious Mark Twain reference), while girls doing the same is terrifying; it's by no means something the film develops, but it's there.

None of this is to say that there aren't pleasures here: all eight of the performances work, quite well. Sledge is adorably ebullient, Shusterov's nervous mumbling is tremendously humane, Hannah Freiman (from Chapter 3) exudes raw, confused terror quite well. Leigh's shy, sad baby of a character is heartbreaking, giving us the sense that Aviva has receded into a protective shell, having grown not at all from her experiences and quite apparently having been damaged by them. The best of the Avivas is Sharon Wilkins, who plays the character in the long, expansive Chapter 6, "Mama Sunshine"; she's physically the outlier of the group, an extremely overweight African-American woman, but she gets the closest to the confused, wary core of the character. She plays a mumbling, nervous runaway surrounded by friendly people who would hate her if they knew the truth about her past so precisely that it becomes quite impossible to remember that she's a fully-grown adult, looming over her castmates, even when you're looking straight at her doing so.

I don't want to give the film too much grief for its central casting conceit, then: it has given us quite a few marvelous performances to enjoy. At the same time, it's so much: this is the kind of huge, Brechtian-style gesture that so completely dominates the movie regardless of everything else within it, that it damn well better be doing something important. And I simply don't see that it is: it seems stuck entirely at the level of "what would happen if we tried..." I doubt that I'd have ever loved Palindromes, but I think I could at least remotely admire it, if not for the way its major central idea leaves it so emotionally distant.