Blockbuster History: Storms at sea

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: in Adrift, we get to see the real-life results of riding a small boat through a hurricane. Historically, the results are bad.

Wolfgang Peterson is an odd one. If one were to cherry-pick just the very best of the best of his 14 features, it would make him look like one of the all-timers: the stressful, exhausting submarine movie to end all submarine movies Das Boot, from 1981; the generation-defining 1984 fantasy The NeverEnding Story; one of the great specimens of '90s action cinema, In the Line of Fire; and if I'm feeling generous, the much-less-great but still pleasant '90s action movie Air Force One. And yet, how could we truly call "great" the filmmaker who also made the draggy Outbreak in 1995 and the dreary Poseidon in 2006? I bring up this last film, which every decent person has long since forgotten about, for the particular reason that, as bad as it is, it's the end of what we might as well call Peterson's "Bad Things Happen at Sea" cycle, which began with Das Boot and middled with our current subject, the 2000 popcorn tragedy The Perfect Storm. Not to spoil the review or anything, but you'll note that I didn't list this one when I was cherry-picking.

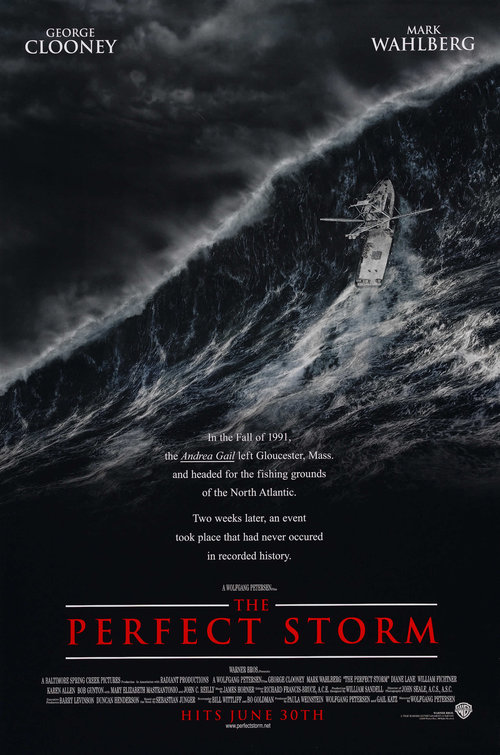

The film, written by Bill Wittliff, is based on Sebastian Junger's 1997 fictionalised non-fiction account of the 1991 "Perfect Storm", an unholy combination of a particularly big nor'easter and a Category 2 hurricane that blasted the whole of the Eastern Seaboard of North America, taking the lives of 13 humans in the process. Six of those were, spoiler alert, the crew of the Andrea Gail, a fishing boat out of Gloucester, Massachusetts, and it was the story of these men's death that formed the bulk of Junger's book. It's a weird thing to have a major summer tentpole movie that so forthrightly announced itself as the true story of how all the protagonists drowned - and that was very much front-and-center in the marketing of the movie back in the summer of 2000, when this became a big hit - but I think it's a good window into how The Perfect Storm applies itself to the task of being a giant crowd-pleasing summer movie. That is, it's a sort of awful, trivialising affair, one that led to two of the families of the dead men suing the filmmakers, and a third man's sister talking to the media about how much her brother was nothing like he seemed in the movie.

Put another way, this is a film that, beyond cynically, tells the story of the crew of the Andrea Gail not for the sake, but because the book was a big success, and because the turn of the millennium was a hot time for movies that could be sold entirely on the basis of their groundbreaking special effects, and because Titanic had just proven that people dying in visually spectacular shipwrecks in the Grand Banks region could mean huge box office. But we needn't appeal to the fact that this was all a true story to find it horribly dispiriting how the film treats its characters: it does a perfectly bad job just as a self-contained story in its own right.

The plot part of the movie is pretty straightforward. Captain Billy Tyne (George Clooney, in one of the very last roles of the "oh, you dumb TV actor, trying to be a movie star" phase of his career) has just returned to port, with a none-too-impressive haul of fish. Without actually saying it, the owner of the Andrea Gail, Bob Brown (Michael Ironside) makes it clear that Tyne will soon not be welcome in his employ if the captain's recent cold streak doesn't snap. In a fit of peevish despair, Tyne decides to take one more trip, in the waning days of the fishing season, out past the Grand Banks of Newfoundland to the Flemish Cap, far enough from any fishing town that it oughtn't be quite so overfished. And so he goes out with a quickly-assembled crew consisting of Bobby Shatford (Mark Walhberg, whose native born Massachusetts accent is awfully lonely in this cast), a neophyte whose relationship to Christina Cotter (Diane Lane) is starting to get really serious; Dale "Murph" Murphy (John C. Reilly), who's trying to make sure his relationship with his son survives his recent divorce; "Bugsy" Moran (John Hawkes), who has no luck with women, but has just managed to successfully flirt with the lonely Irene Johnson (Rusty Schwimmer) the very night before putting out to sea; David "Sully" Sullivan (William Fichtner), who has a long rivalry with Murph; and Alfred Pierre (Allen Payne), who has absolutely no personality and all, and in a stunning coincidence is also the solitary black person in the movie.

So that paragraph includes the entirety of what we get for character development in the whole movie. And that is much of the problem: since the hurricane and the sinking of the boat can really only account for a fragment of the running time, we spend a huge portion of the movie watching the six men go through their extremely uncompelling dramatic arcs (or really five, if we discount Alfred, and really four, since Sully is just a complication for Murph). The acting does not help out with this at all: it hardly needs mentioning that old-hat character actors like Reilly, Hawkes, and Fichtner can do great work with nothing parts, but they're not doing it here (Reilly, especially, sleepwalks through a trite part that nevertheless could surely have produced more). It's no surprise, then, that the less-reliable cast members can't deal with the underwritten characters, and that's not all of it: Lane is so lost that she manages to do a bad job of opening a window and then looking out of it. The only standout is Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio as Tyne's friendly rival captain Linda Greenlaw, and she gets hardly any screentime to make her striking impression.

With no interesting characters, the film basically consists of 80 minutes of tacky sentiment (the film opens with a mournful, lingering pan over a memorial plaque commemorating the Gloucester fisherman who've died at sea over the years, and it never really gets less thumping in its in appeals to Noble Sacrifice than that), augmented by John Seale's sunset-heavy cinematography, and James Horner's shameless, shameless music (it sounds like his scores for Apollo 13 and Titanic had a baby). Once the storm kicks up, the film at least starts to justify itself: the CGI waves and lumbering clouds haven't aged terribly well, but they were convincing enough in 2000 to net the film an Oscar nomination (so did the sound, which has aged well: the dialogue was almost 100% re-recorded in post-production when that was still uncommon, and it sounds terrific). The film does a good job of making the ocean seem very big and the Andrea Gail very small, which is at a certain point the only thing it absolutely must provide.

Still, it would be nice if it did more than it must. The spectacle isn't spectacular enough, nor is there enough of it (in a film that just grinds on and on through its 130 minutes, including a distracting and unnecessary subplot about another ship in the storm) to justify how boring it is to keep company with the non-people in the cast. The film has too obviously been made for the most mechanically commercial reasons, and that lack of passion or real belief in the story lays over the movie like a thick, suffocating blanket of the most tedious mediocrity. This should be a harrowing, grandiose nightmare of a film; instead, it's just annoying and long, and the total lack of interesting humans at the mercy of the waves is most of the reason why.

Wolfgang Peterson is an odd one. If one were to cherry-pick just the very best of the best of his 14 features, it would make him look like one of the all-timers: the stressful, exhausting submarine movie to end all submarine movies Das Boot, from 1981; the generation-defining 1984 fantasy The NeverEnding Story; one of the great specimens of '90s action cinema, In the Line of Fire; and if I'm feeling generous, the much-less-great but still pleasant '90s action movie Air Force One. And yet, how could we truly call "great" the filmmaker who also made the draggy Outbreak in 1995 and the dreary Poseidon in 2006? I bring up this last film, which every decent person has long since forgotten about, for the particular reason that, as bad as it is, it's the end of what we might as well call Peterson's "Bad Things Happen at Sea" cycle, which began with Das Boot and middled with our current subject, the 2000 popcorn tragedy The Perfect Storm. Not to spoil the review or anything, but you'll note that I didn't list this one when I was cherry-picking.

The film, written by Bill Wittliff, is based on Sebastian Junger's 1997 fictionalised non-fiction account of the 1991 "Perfect Storm", an unholy combination of a particularly big nor'easter and a Category 2 hurricane that blasted the whole of the Eastern Seaboard of North America, taking the lives of 13 humans in the process. Six of those were, spoiler alert, the crew of the Andrea Gail, a fishing boat out of Gloucester, Massachusetts, and it was the story of these men's death that formed the bulk of Junger's book. It's a weird thing to have a major summer tentpole movie that so forthrightly announced itself as the true story of how all the protagonists drowned - and that was very much front-and-center in the marketing of the movie back in the summer of 2000, when this became a big hit - but I think it's a good window into how The Perfect Storm applies itself to the task of being a giant crowd-pleasing summer movie. That is, it's a sort of awful, trivialising affair, one that led to two of the families of the dead men suing the filmmakers, and a third man's sister talking to the media about how much her brother was nothing like he seemed in the movie.

Put another way, this is a film that, beyond cynically, tells the story of the crew of the Andrea Gail not for the sake, but because the book was a big success, and because the turn of the millennium was a hot time for movies that could be sold entirely on the basis of their groundbreaking special effects, and because Titanic had just proven that people dying in visually spectacular shipwrecks in the Grand Banks region could mean huge box office. But we needn't appeal to the fact that this was all a true story to find it horribly dispiriting how the film treats its characters: it does a perfectly bad job just as a self-contained story in its own right.

The plot part of the movie is pretty straightforward. Captain Billy Tyne (George Clooney, in one of the very last roles of the "oh, you dumb TV actor, trying to be a movie star" phase of his career) has just returned to port, with a none-too-impressive haul of fish. Without actually saying it, the owner of the Andrea Gail, Bob Brown (Michael Ironside) makes it clear that Tyne will soon not be welcome in his employ if the captain's recent cold streak doesn't snap. In a fit of peevish despair, Tyne decides to take one more trip, in the waning days of the fishing season, out past the Grand Banks of Newfoundland to the Flemish Cap, far enough from any fishing town that it oughtn't be quite so overfished. And so he goes out with a quickly-assembled crew consisting of Bobby Shatford (Mark Walhberg, whose native born Massachusetts accent is awfully lonely in this cast), a neophyte whose relationship to Christina Cotter (Diane Lane) is starting to get really serious; Dale "Murph" Murphy (John C. Reilly), who's trying to make sure his relationship with his son survives his recent divorce; "Bugsy" Moran (John Hawkes), who has no luck with women, but has just managed to successfully flirt with the lonely Irene Johnson (Rusty Schwimmer) the very night before putting out to sea; David "Sully" Sullivan (William Fichtner), who has a long rivalry with Murph; and Alfred Pierre (Allen Payne), who has absolutely no personality and all, and in a stunning coincidence is also the solitary black person in the movie.

So that paragraph includes the entirety of what we get for character development in the whole movie. And that is much of the problem: since the hurricane and the sinking of the boat can really only account for a fragment of the running time, we spend a huge portion of the movie watching the six men go through their extremely uncompelling dramatic arcs (or really five, if we discount Alfred, and really four, since Sully is just a complication for Murph). The acting does not help out with this at all: it hardly needs mentioning that old-hat character actors like Reilly, Hawkes, and Fichtner can do great work with nothing parts, but they're not doing it here (Reilly, especially, sleepwalks through a trite part that nevertheless could surely have produced more). It's no surprise, then, that the less-reliable cast members can't deal with the underwritten characters, and that's not all of it: Lane is so lost that she manages to do a bad job of opening a window and then looking out of it. The only standout is Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio as Tyne's friendly rival captain Linda Greenlaw, and she gets hardly any screentime to make her striking impression.

With no interesting characters, the film basically consists of 80 minutes of tacky sentiment (the film opens with a mournful, lingering pan over a memorial plaque commemorating the Gloucester fisherman who've died at sea over the years, and it never really gets less thumping in its in appeals to Noble Sacrifice than that), augmented by John Seale's sunset-heavy cinematography, and James Horner's shameless, shameless music (it sounds like his scores for Apollo 13 and Titanic had a baby). Once the storm kicks up, the film at least starts to justify itself: the CGI waves and lumbering clouds haven't aged terribly well, but they were convincing enough in 2000 to net the film an Oscar nomination (so did the sound, which has aged well: the dialogue was almost 100% re-recorded in post-production when that was still uncommon, and it sounds terrific). The film does a good job of making the ocean seem very big and the Andrea Gail very small, which is at a certain point the only thing it absolutely must provide.

Still, it would be nice if it did more than it must. The spectacle isn't spectacular enough, nor is there enough of it (in a film that just grinds on and on through its 130 minutes, including a distracting and unnecessary subplot about another ship in the storm) to justify how boring it is to keep company with the non-people in the cast. The film has too obviously been made for the most mechanically commercial reasons, and that lack of passion or real belief in the story lays over the movie like a thick, suffocating blanket of the most tedious mediocrity. This should be a harrowing, grandiose nightmare of a film; instead, it's just annoying and long, and the total lack of interesting humans at the mercy of the waves is most of the reason why.