The imperial presidency

A review requested by Not Fenimore, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

No matter what the industry might like to say about itself every year at the Oscar, Hollywood films are, as a rule and by conscious design, ruthlessly stripped of political content (unless it's political content about the safely distant past). Hollywood films are in the business of making money from the largest possible audience, both within the United States and without, and taking explicit political stances is generally not a good strategy for making that happen.* So it should already make us take notice as something at least a little bit strange when a Hollywood film goes all-in on promoting specific policies.

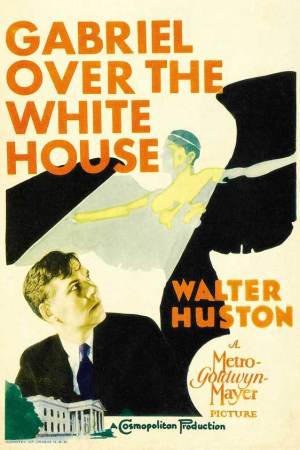

There's nothing "a little bit" strange about Gabriel Over the White House, a 1933 film produced by Walter Wanger for Cosmopolitan Pictures, and released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. It is quite possibly the most baffling political message film ever financed by a major studio and commercially released, though that commercial release only barely happened; MGM head Louis B. Mayer had grave doubts about the film's morality and toyed with burying it. As it stands, he was able to delay it for a while, though what good the delay did anybody, I cannot say.

So anyway, Gabriel Over the White House is the pro-dictator movie that MGM made that one time. Specifically, it's about how the problems facing the U.S. during the Great Depression could only be solved by a strongman making the hard decisions, as long as he was making those hard decisions from a left-wing perspective. But, like, moderately left-wing, none of that Communist stuff. It's basically Third Way propaganda, except if the other two ways were Benito Mussolini and Josef Stalin.

The film opens more or less at the exact moment that Judson C. Hammond (Walter Huston) is elected President, as part of an overall wave election that puts his party in power, with everybody very excited for the crony politics that are about to make them all very rich. This putters on for about a third of the 86-minute-long film (a good chunk shorter than its initial cut, edited in the hope of downplaying the worst of its message, and to remove an assassination attempt scene), with Hammond being pretty much shitty and craven, and surrounded by a bunch of equally shitty and craven men; the only real spot of light is his personal secretary, Hartley "Beek" Beekman (Franchot Tone), apparently the only hard-working moral man in Washington.

Things change when Hammond ends up in a car accident that puts him into a coma; during that time, he is visited by a cautiously nondescript gust of wind and shaft of light - possibly the archangel Gabriel, though despite the film's title going right there, the film proper remains hugely agnostic. Whatever it was, Hammond emerges from his coma a changed man: a morally stern crusader willing to do whatever it takes to right the problems facing America, whether it involves creating jobs for the armies of the unemployed by force of will, having bootleggers and gangsters executed after Soviet-style show trials, or coercing the rest of the world's nations into disarmament and peace by threatning to blow up the entire planet if he doesn't get his way.

Frankly, I don't have the god-damnedest idea what to do with any of this, other than to admire the gutsiness of its naïveté. If Warners had put this out, there'd be little to no doubt that it was a full-throated endorsement of Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose backstory vaguely resembles Hammond's (a patrician figure, well-connected in party politics, who went full-on class traitor in order to get things working again for the multitudes of the unemployed and poor), and who would, later in the 1930s, do more to invest the presidency with autocratic power than any other individual until... ever? George W. Bush? But that's suggesting something like clairvoyance on behalf of the filmmakers, working before the 1932 election had been held.

Anyway, trying to map Gabriel Over the White House onto anything like real-world politics is just plain goofy; this is a fantasy, pure and simple. The big takeaway here seems to be that somebody had ought to do something about the problems, darn it, and if the laws get in the way of him doing it, then the laws should just be revoked. It's adorably optimistic, almost; suggesting a level of genuine hope that good men given unlimited power will become even better men and Spoiler Alert, but really, I don't see how it's remotely possible to spoil the manifestly strange power of this movie; still, Spoiler Alert as soon as they've done their duty in manifesting God's plan, they'll die anyway, so it's not like we've invested dictatorial authority in someone who'd actually become a dictator for life. I mean, he does, but it's a real short life.

Anyway, it's interesting mostly for laying bare the hero-worship and sublimated desire for a benevolent tyrant that bubbles just underneath so much of American democracy, though I think it has grown stronger since the Reagan presidency than it was prior to then (maybe it's just that I've really only been paying attention in the 21st Century, though if nothing else, it was never explicit prior to the Donald Trump election campaign). I think it really matters a lot that Hammond's great successes are all left-wing, starting with his beneficent engagement with the hordes of desperate, unemployed men. The big totalitarian movements of the '30s were all right-wing: the Nazis, the Fascists, the Japanese imperialists, the Spanish Nationalists. By the time of Gabriel Over the White House, only the Fascists had really manifested, but there's still a definite vibe of "well, if their side can do it, why not ours?" just barely peeking out around the corners of the film. It's what pushes this from mildly disturbing to mildly disturbing and really fucking weird.

The weirdness is something to cling to. As propaganda for maybe the most single off-limits political idea one could hold in the United States, Gabriel Over the White House is honestly pretty drab and dull. Huston, at least, is genuinely great in the film - the only thing here for which the term "great" needs to bother showing up - bringing a pleasantly flippant meanness to the pre-reformed Hammond, and a warmth that cuts against the peremptory prickliness the script places on the character once he asserts himself. And director Gregory La Cava, who is I think quite underrated for the most part, is up to some interesting things in the first part; La Cava's gift was in capturing the seediness of everyday life in a way that didn't spoil the fun of glossy movie charm (his best film, My Man Godfrey, is a high-society screwball comedy doubling as a message movie about homelessness after all), and the chance to documentary the genial wickenedness of political corruption in Washington seems to have captured his imagination; the negative fascination with how parties work is like nothing else that side of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and that film is of course as carefully denuded of real politics as possible; Gabriel Over the White House is an unstinting message film, so that depiction of corruption has more of a hard-edged observational tone to it.

La Cava doesn't exactly bail out on the film once it goes in for authoritarianism; he and cinematographer Bert Glennon put in lots of literally sanctifying images of Hammond as an icon and moral light. As in, there's a scene where he stands surrounded by the ranks of the unemployed, and Huston has one carefully-aimed spotlight making him considerably brighter than everything else in the composition, but it's been arranged so that he appears to be glowing with some kind of internal holy force. It's a hell of a something, anyway.

What does happen in the last hour is that Carey Wilson's adapted screenplay starts to get very drearily talky: it's not just about the desirability of totalitarianism, it's about the bureaucracy of totalitarianism. Which is even weirder still, in its own right. But while the basic logline of Gabriel Over the White House promises a car crash of unmatched tawdriness, the actual effect of watching it is a series of lurches between repulsion, confusion, and endless boredom, as the movie really digs into the minutiae of Washington wrangling. The great propagandists for dictators understood that what you really need is an artful emotional appeal, and that's how we get the masterpieces of Leni Riefenstahl or decades' worth of rousing Soviet message movies. Somehow, despite being the most batshit crazy movie about American politics ever made, Gabriel Over the White House is also too sedate and sober-minded for its own good. The result is a damned hard film to parse and to talk about, and a film that's quite impossible to recommend; and yet, I think if you ever stumble across it, you will not find a more rewardingly fucked-up and inexplicable 86 minutes could ever be spent. This is a handsome, smart movie; a horrible, psychopathic movie; and a drowsy movie all built into one body, and it's a body with the single oddest political message ever offered by a major Hollywood studio. What's not to love? Other than "absolutely every last thing", I mean.

*There are exceptions, of course, as there always are: during the Depression, Warner Bros. in particular enthusiastically turned out as many left-wing message movies as the censors let it get away with, and there's the obvious matter of World War II and its glut of propaganda films. As an overall tendency, though, the principle that American studio films subscribe to a politically neutered philosophy - albeit reflexively pro-republicanism (with a lowercase "r"), pro-capitalism, and generally pro-military - seems so self-evident that I think it hardly needs defending.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

No matter what the industry might like to say about itself every year at the Oscar, Hollywood films are, as a rule and by conscious design, ruthlessly stripped of political content (unless it's political content about the safely distant past). Hollywood films are in the business of making money from the largest possible audience, both within the United States and without, and taking explicit political stances is generally not a good strategy for making that happen.* So it should already make us take notice as something at least a little bit strange when a Hollywood film goes all-in on promoting specific policies.

There's nothing "a little bit" strange about Gabriel Over the White House, a 1933 film produced by Walter Wanger for Cosmopolitan Pictures, and released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. It is quite possibly the most baffling political message film ever financed by a major studio and commercially released, though that commercial release only barely happened; MGM head Louis B. Mayer had grave doubts about the film's morality and toyed with burying it. As it stands, he was able to delay it for a while, though what good the delay did anybody, I cannot say.

So anyway, Gabriel Over the White House is the pro-dictator movie that MGM made that one time. Specifically, it's about how the problems facing the U.S. during the Great Depression could only be solved by a strongman making the hard decisions, as long as he was making those hard decisions from a left-wing perspective. But, like, moderately left-wing, none of that Communist stuff. It's basically Third Way propaganda, except if the other two ways were Benito Mussolini and Josef Stalin.

The film opens more or less at the exact moment that Judson C. Hammond (Walter Huston) is elected President, as part of an overall wave election that puts his party in power, with everybody very excited for the crony politics that are about to make them all very rich. This putters on for about a third of the 86-minute-long film (a good chunk shorter than its initial cut, edited in the hope of downplaying the worst of its message, and to remove an assassination attempt scene), with Hammond being pretty much shitty and craven, and surrounded by a bunch of equally shitty and craven men; the only real spot of light is his personal secretary, Hartley "Beek" Beekman (Franchot Tone), apparently the only hard-working moral man in Washington.

Things change when Hammond ends up in a car accident that puts him into a coma; during that time, he is visited by a cautiously nondescript gust of wind and shaft of light - possibly the archangel Gabriel, though despite the film's title going right there, the film proper remains hugely agnostic. Whatever it was, Hammond emerges from his coma a changed man: a morally stern crusader willing to do whatever it takes to right the problems facing America, whether it involves creating jobs for the armies of the unemployed by force of will, having bootleggers and gangsters executed after Soviet-style show trials, or coercing the rest of the world's nations into disarmament and peace by threatning to blow up the entire planet if he doesn't get his way.

Frankly, I don't have the god-damnedest idea what to do with any of this, other than to admire the gutsiness of its naïveté. If Warners had put this out, there'd be little to no doubt that it was a full-throated endorsement of Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose backstory vaguely resembles Hammond's (a patrician figure, well-connected in party politics, who went full-on class traitor in order to get things working again for the multitudes of the unemployed and poor), and who would, later in the 1930s, do more to invest the presidency with autocratic power than any other individual until... ever? George W. Bush? But that's suggesting something like clairvoyance on behalf of the filmmakers, working before the 1932 election had been held.

Anyway, trying to map Gabriel Over the White House onto anything like real-world politics is just plain goofy; this is a fantasy, pure and simple. The big takeaway here seems to be that somebody had ought to do something about the problems, darn it, and if the laws get in the way of him doing it, then the laws should just be revoked. It's adorably optimistic, almost; suggesting a level of genuine hope that good men given unlimited power will become even better men and Spoiler Alert, but really, I don't see how it's remotely possible to spoil the manifestly strange power of this movie; still, Spoiler Alert as soon as they've done their duty in manifesting God's plan, they'll die anyway, so it's not like we've invested dictatorial authority in someone who'd actually become a dictator for life. I mean, he does, but it's a real short life.

Anyway, it's interesting mostly for laying bare the hero-worship and sublimated desire for a benevolent tyrant that bubbles just underneath so much of American democracy, though I think it has grown stronger since the Reagan presidency than it was prior to then (maybe it's just that I've really only been paying attention in the 21st Century, though if nothing else, it was never explicit prior to the Donald Trump election campaign). I think it really matters a lot that Hammond's great successes are all left-wing, starting with his beneficent engagement with the hordes of desperate, unemployed men. The big totalitarian movements of the '30s were all right-wing: the Nazis, the Fascists, the Japanese imperialists, the Spanish Nationalists. By the time of Gabriel Over the White House, only the Fascists had really manifested, but there's still a definite vibe of "well, if their side can do it, why not ours?" just barely peeking out around the corners of the film. It's what pushes this from mildly disturbing to mildly disturbing and really fucking weird.

The weirdness is something to cling to. As propaganda for maybe the most single off-limits political idea one could hold in the United States, Gabriel Over the White House is honestly pretty drab and dull. Huston, at least, is genuinely great in the film - the only thing here for which the term "great" needs to bother showing up - bringing a pleasantly flippant meanness to the pre-reformed Hammond, and a warmth that cuts against the peremptory prickliness the script places on the character once he asserts himself. And director Gregory La Cava, who is I think quite underrated for the most part, is up to some interesting things in the first part; La Cava's gift was in capturing the seediness of everyday life in a way that didn't spoil the fun of glossy movie charm (his best film, My Man Godfrey, is a high-society screwball comedy doubling as a message movie about homelessness after all), and the chance to documentary the genial wickenedness of political corruption in Washington seems to have captured his imagination; the negative fascination with how parties work is like nothing else that side of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and that film is of course as carefully denuded of real politics as possible; Gabriel Over the White House is an unstinting message film, so that depiction of corruption has more of a hard-edged observational tone to it.

La Cava doesn't exactly bail out on the film once it goes in for authoritarianism; he and cinematographer Bert Glennon put in lots of literally sanctifying images of Hammond as an icon and moral light. As in, there's a scene where he stands surrounded by the ranks of the unemployed, and Huston has one carefully-aimed spotlight making him considerably brighter than everything else in the composition, but it's been arranged so that he appears to be glowing with some kind of internal holy force. It's a hell of a something, anyway.

What does happen in the last hour is that Carey Wilson's adapted screenplay starts to get very drearily talky: it's not just about the desirability of totalitarianism, it's about the bureaucracy of totalitarianism. Which is even weirder still, in its own right. But while the basic logline of Gabriel Over the White House promises a car crash of unmatched tawdriness, the actual effect of watching it is a series of lurches between repulsion, confusion, and endless boredom, as the movie really digs into the minutiae of Washington wrangling. The great propagandists for dictators understood that what you really need is an artful emotional appeal, and that's how we get the masterpieces of Leni Riefenstahl or decades' worth of rousing Soviet message movies. Somehow, despite being the most batshit crazy movie about American politics ever made, Gabriel Over the White House is also too sedate and sober-minded for its own good. The result is a damned hard film to parse and to talk about, and a film that's quite impossible to recommend; and yet, I think if you ever stumble across it, you will not find a more rewardingly fucked-up and inexplicable 86 minutes could ever be spent. This is a handsome, smart movie; a horrible, psychopathic movie; and a drowsy movie all built into one body, and it's a body with the single oddest political message ever offered by a major Hollywood studio. What's not to love? Other than "absolutely every last thing", I mean.

*There are exceptions, of course, as there always are: during the Depression, Warner Bros. in particular enthusiastically turned out as many left-wing message movies as the censors let it get away with, and there's the obvious matter of World War II and its glut of propaganda films. As an overall tendency, though, the principle that American studio films subscribe to a politically neutered philosophy - albeit reflexively pro-republicanism (with a lowercase "r"), pro-capitalism, and generally pro-military - seems so self-evident that I think it hardly needs defending.