Pictures worth a thousand words

In ten feature-length documentaries made over a 35-year span, Errol Morris has played with different styles, different tones, different genres (he is, in no small part, the reason we can speak about "different genres" of documentary film in the first place), and different intentions, but one thing has remained constant. Ten times out of ten, he calculatedly positions himself as an outsider, fighting tooth and nail to find some path in to the innermost truth of whatever it is that he's trained his camera on, with the clear assumption that the artist's relationship to his subject is at least slightly antagonist and dubious. He finds people fascinating and worth of affection; but he also finds them to be deft liars - often so deft, they don't know that they're doing it.

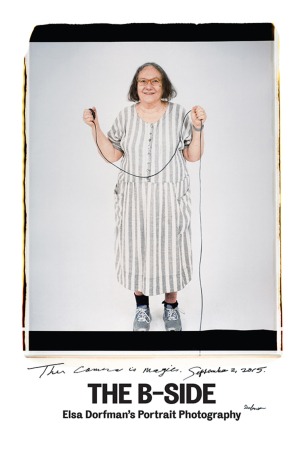

So if nothing else, The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman's Portrait Photography counts as the biggest break Morris has ever made from his traditional method of working. The director's eleventh non-fiction feature is also the first thing he's ever made that I would primarily describe as "nice". Elsa Dorfman, the film's subject isn't somebody that Morris chooses to fence with; she's somebody that he's content to sit in front of, basking in her presence and uncritically soaking in her lifetime of accumulated wisdom.

If that almost necessarily means that The B-Side is probably the most acutely "minor" film Morris has made, so be it. I will say this on its behalf, at least: the director makes an excellent case for Dorfman as a hell of a human being and a hell of an artist, somebody who's more than worthy of the tidy little love letter that Morris here provides. (I suppose I should offer this bit of disclosure: I was in the audience of the film's world premiere, as was Dorfman, who received a besotted standing ovation at the end of it. I also had a chance to briefly chat with her later on, and my God but she is a hell of a human being, and seemingly too self-deprecating to be aware of it. So yes, I'm unquestionably biased).

"And who," you are surely wondering by this point, "is Elsa Dorfman?" Answering that question is the project of the film, of course, but for starters, she's a very lovely 80-year-old woman who lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts, just down the street from Errol Morris himself, and that's certainly not an incidental part of why The B-Side is so warm and friendly - the filmmaker and the subject are friends. But of course Morris undoubtedly has lots of friends that he doesn't make the subject of documentaries, and that gets us to Dorfman's more significant claim to historical importance. She is a woman who, in her early adulthood in New York, started to cross the paths of several major figures in the East Coast literary scene, most significantly Allen Ginsburg, who became a great friend till the end of his life. Somewhere along the way, her connections in the publishing world paved the way to her 1974 book of photographs, Elsa's Housebook: A Woman's Photojournal, collecting a few years' worth of carefully candid snapshots of life and the people she knew.

Skip ahead a bit, and Dorfman became one of the small number of artists to work extensively with Polaroid's rare large-format self-developing film (in part through blind chance - in addition to Dorfman and Morris, Cambridge is also the home of the Polaroid Corporation - and in part through doggedness, bothering the Polaroid people until they finally agreed to let her lease one of the small number of large-format cameras indefinitely), and she spend most of the '80s, '90s, and '00s as a portrait photographer, taking two photographs of her clients. They could choose to take one of the 20" x 24" prints home, and the reject would end up in Dorfman's permanent collection - the B-sides of the title.

There's nothing flashy or complex about the movie whatsoever. Morris sets up a few cameras in a circle around Dorfman as she sits in her archive, to facilitate cutting, and lets her talk at length about her work process, the challenges of being a woman artist at different points in history, and her philosophies of art, all of them stirred up in no particular order. Dorfman plainly doesn't regard herself as interesting enough to be the subject of a movie, and Morris doesn't necessarily force her; until the words "Allen Ginsburg" are first spoken, there's nothing in The B-Side to make you think this is anything other than one of Morris's "colorful local eccentric" portraits, in the Gates of Heaven/Fast, Cheap & Out of Control mode. And even though Dorfman turns out to be rather more significant (if no less eccentric) than the subjects of those movies, that is the version of Morris we're closest to here, the more laid-back, "let's see what people are like when you get to know them" phase of his career that he largely abandoned in the 2000s. But I would maybe call this my favorite of all Morrises (I've increasingly come around to the position of Roger Ebert, that Gates of Heaven is his masterpiece and one of the singularly important works of modern American cinema), and seeing him return to that mode is an exceptional pleasure.

So anyway, the point of all this is that we spend a short time that feels longer - the film is 76 minutes, and I'll admit that they're not very well-paced - getting to hang out with Elsa, looking at a lot of her photographs, hearing her talk about what she thinks happens inside people's brains when they've got a camera on them. She has the admirable directness of age, and watching her talk about her photographs becomes an engaging lecture in seeing somebody who knows a hell of a lot about portrait photography frankly dissecting what does or doesn't work in any given image, free of ego but also free of feigned modesty. Along the way, she drops casually profound thoughts about the relationship of the medium and the art, the medium and the artist, and without her ever stridently declaring a biographical theory of everything, it becomes very clear that if there had never been self-developing 20" x 24" Polaroid film, it's very unlikely that the particular Elsa Dorfman we see before us would have ever come into being.

Which would be a heinous shame, because that Elsa Dorfman is an amazingly thoughtful, insightful person, and very much worth getting to know. The pleasures of The B-Side are the simplest kind, as old as the act of storytelling: hearing someone who has lived a full life describing their experiences in a synthetic, overarching narrative, with lessons for us all if we want them, or just the joy of hearing a natural raconteur (who would undoubtedly consider herself much too shy for such a word) toss ideas and stories in the air. It is, in effect, a film about rapturously staring at a very awesome old person and hearing what they have to say. It's not challenging or artistically ravishing or anything like that, but it forges a penetrating, enriching human connection between the viewer and the subject, and if that's not the stuff of excellent cinema, then what possibly could be?

So if nothing else, The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman's Portrait Photography counts as the biggest break Morris has ever made from his traditional method of working. The director's eleventh non-fiction feature is also the first thing he's ever made that I would primarily describe as "nice". Elsa Dorfman, the film's subject isn't somebody that Morris chooses to fence with; she's somebody that he's content to sit in front of, basking in her presence and uncritically soaking in her lifetime of accumulated wisdom.

If that almost necessarily means that The B-Side is probably the most acutely "minor" film Morris has made, so be it. I will say this on its behalf, at least: the director makes an excellent case for Dorfman as a hell of a human being and a hell of an artist, somebody who's more than worthy of the tidy little love letter that Morris here provides. (I suppose I should offer this bit of disclosure: I was in the audience of the film's world premiere, as was Dorfman, who received a besotted standing ovation at the end of it. I also had a chance to briefly chat with her later on, and my God but she is a hell of a human being, and seemingly too self-deprecating to be aware of it. So yes, I'm unquestionably biased).

"And who," you are surely wondering by this point, "is Elsa Dorfman?" Answering that question is the project of the film, of course, but for starters, she's a very lovely 80-year-old woman who lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts, just down the street from Errol Morris himself, and that's certainly not an incidental part of why The B-Side is so warm and friendly - the filmmaker and the subject are friends. But of course Morris undoubtedly has lots of friends that he doesn't make the subject of documentaries, and that gets us to Dorfman's more significant claim to historical importance. She is a woman who, in her early adulthood in New York, started to cross the paths of several major figures in the East Coast literary scene, most significantly Allen Ginsburg, who became a great friend till the end of his life. Somewhere along the way, her connections in the publishing world paved the way to her 1974 book of photographs, Elsa's Housebook: A Woman's Photojournal, collecting a few years' worth of carefully candid snapshots of life and the people she knew.

Skip ahead a bit, and Dorfman became one of the small number of artists to work extensively with Polaroid's rare large-format self-developing film (in part through blind chance - in addition to Dorfman and Morris, Cambridge is also the home of the Polaroid Corporation - and in part through doggedness, bothering the Polaroid people until they finally agreed to let her lease one of the small number of large-format cameras indefinitely), and she spend most of the '80s, '90s, and '00s as a portrait photographer, taking two photographs of her clients. They could choose to take one of the 20" x 24" prints home, and the reject would end up in Dorfman's permanent collection - the B-sides of the title.

There's nothing flashy or complex about the movie whatsoever. Morris sets up a few cameras in a circle around Dorfman as she sits in her archive, to facilitate cutting, and lets her talk at length about her work process, the challenges of being a woman artist at different points in history, and her philosophies of art, all of them stirred up in no particular order. Dorfman plainly doesn't regard herself as interesting enough to be the subject of a movie, and Morris doesn't necessarily force her; until the words "Allen Ginsburg" are first spoken, there's nothing in The B-Side to make you think this is anything other than one of Morris's "colorful local eccentric" portraits, in the Gates of Heaven/Fast, Cheap & Out of Control mode. And even though Dorfman turns out to be rather more significant (if no less eccentric) than the subjects of those movies, that is the version of Morris we're closest to here, the more laid-back, "let's see what people are like when you get to know them" phase of his career that he largely abandoned in the 2000s. But I would maybe call this my favorite of all Morrises (I've increasingly come around to the position of Roger Ebert, that Gates of Heaven is his masterpiece and one of the singularly important works of modern American cinema), and seeing him return to that mode is an exceptional pleasure.

So anyway, the point of all this is that we spend a short time that feels longer - the film is 76 minutes, and I'll admit that they're not very well-paced - getting to hang out with Elsa, looking at a lot of her photographs, hearing her talk about what she thinks happens inside people's brains when they've got a camera on them. She has the admirable directness of age, and watching her talk about her photographs becomes an engaging lecture in seeing somebody who knows a hell of a lot about portrait photography frankly dissecting what does or doesn't work in any given image, free of ego but also free of feigned modesty. Along the way, she drops casually profound thoughts about the relationship of the medium and the art, the medium and the artist, and without her ever stridently declaring a biographical theory of everything, it becomes very clear that if there had never been self-developing 20" x 24" Polaroid film, it's very unlikely that the particular Elsa Dorfman we see before us would have ever come into being.

Which would be a heinous shame, because that Elsa Dorfman is an amazingly thoughtful, insightful person, and very much worth getting to know. The pleasures of The B-Side are the simplest kind, as old as the act of storytelling: hearing someone who has lived a full life describing their experiences in a synthetic, overarching narrative, with lessons for us all if we want them, or just the joy of hearing a natural raconteur (who would undoubtedly consider herself much too shy for such a word) toss ideas and stories in the air. It is, in effect, a film about rapturously staring at a very awesome old person and hearing what they have to say. It's not challenging or artistically ravishing or anything like that, but it forges a penetrating, enriching human connection between the viewer and the subject, and if that's not the stuff of excellent cinema, then what possibly could be?

Categories: documentaries, errol morris, warm fuzzies