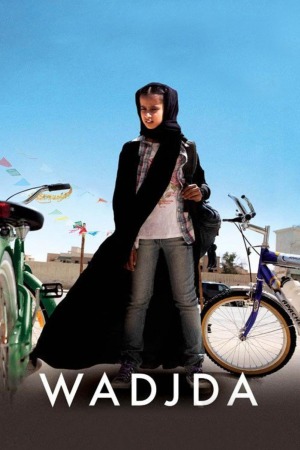

The girl and the bike

A review requested by a contributor who wishes to remain anonymous, with thanks for donating to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

The second-most interesting thing about the 2012 film Wadjda is that it the first movie shot, in its entirety, in Saudi Arabia. The most interesting thing is that it was the first feature film directed by a Saudi woman. Let's be clear, that's not a way of slighting the rest of the film - those are both very distinctive achievements, enough to make Wadjda one of the most singularly groundbreaking movies of the 2010s.

The film hiding beneath those milestones is certainly not groundbreaking. Writer-director Haifaa al-Mansour by her admission took inspiration from Vittorio De Sica's 1948 Bicycle Thieves, the film that codified Italian Neorealism as a major artistic force (Wadjda even includes, as a central plot element, a bicycle). And neo-neorealism, over the next several decades, has become the de facto style for socially-conscious filmmakers in emerging and established film industries alike, using the raw material of the real world to tell stories of everyday people. Wadjda makes no effort at all to break from this tendency, though it's hard to fault it: it is socially conscious, after all, deeply concerned with real life and the real world, and especially with the way that women are so horribly subjugated within it.

It's not a polemic, though, but a light little dramedy about a precocious child (another major borrowing from Bicycle Thieves), who finds herself unexpectedly and unhappily intersecting with her country's nastily restrictive treatment of its female citizens. 10-year-old Wadjda (Waad Mohammed), a resident of Riyadh, wants a bike. That's pretty much the beginning and end of it. She wants a bike because her best friend Abdullah (Abdullrahman Al Gohani) already has a bike, and he really wants to race with her, and she wants the same. What neither child has quite grasped, being just young enough that the concerns of adult society are still a strange & ridiculous concept, is that in Saudi Arabia, riding bikes is on the very long list of behaviors considered unacceptable for women. Wadjda's mother (Reem Abdullah) therefore refuses to buy one (she's concerned that the bicycle seat will destroy her daughter's hymen), and Wadjda's father (Sultan Al Assaf) barely seems to care that he even has a daughter, living far apart from his family, as he toys with the idea of taking on a second wife.

And so begins a series of what I can only think to call "shenanigans", as Wadjda tries to scrape up the 800 riyals to buy the bike her own damn self. This causes no small amount of angst and anguish for the adults around her, until she eventually throws herself into studying the Qur'an, surely a sign of her decision to abandon this folly and lean to be a proper Saudi young woman. Or because she's entered a competition based on a knowledge of the Qur'an, with a top prize of 1000 riyals.

It's the last bit that speaks to the spiky sense of humor that Wadjda displays throughout, and which is, I think, the primary reason why it doesn't feel like more of a harangue By all means, the script doesn't shy away from layering its themes and messages on pretty thickly: while the children are treated as naïve innocents, simply trying to go about the business of having fun, the adults are all more or less immediately slotted into obvious, schematic roles, clearly delineating Which Part Of Society They Represent. And the plot involves Wadjda growing aware of the social structure around her, which sees her as bound to an extraordinarily narrow range of possible behaviors, and which views even mild expressions of personal flair as something dubious and wrong-headed. Al-Mansour very clearly has a lesson she wants to teach us about the way women suffer in Saudi Arabia (movie theaters have not existed in that country since the 1980s, and there is only a limited cinema culture; Wadjda was almost certainly designed primarily for export), and leave absolutely no room for missing that lesson.

Still, there's no real value in a sober, grim-faced sociology lesson that's unbearable to watch, and so it turns out that Wadjda is, rather surprisingly, a substantially fun movie. This has everything to do with its star, first-time (and only time) actor Mohammed. Going all the way back to the very dawn of neorealism, Shoeshine, casting child non-actors has been a fairly easy way to guarantee a certain level of adorable appeal for a project; even when things are going horribly for all concerned, the naturalness and lack of self-consciousness that obtains from letting a kid be a kid on camera has done a lot of good for a lot of movies. There's more to Wadjda, and Wadjda, than just plugging a child into a script and letting the magic happen. Mohammed has a terrific ability to project a sense of wary intelligence, figuring out more than the adults around her want her to, and also backing off on what she reveals to them; she's a cunning and thoughtful figure, not a thoughtlessly innocent one, and watching her puts us in the role of silent co-conspirator against the entire edifice of Saudi culture. She's the cool friend who's a little bit more rebellious than we'd ever dare to be, and watching her hack her way through the conflicts facing her is delightful and invigorating, on top of the feeling of righteousness it entails.

Wadjda herself is the secret ingredient that makes the film click so neatly. It's a perfectly satisfactory piece of filmmaking, though hampered by the rule requiring al-Mansour to sit in a van during the exterior scenes - of which there are many - communicating with the cast and crew (mostly imported from Germany) via walkie-talkies. The result is a certain brittleness in how the scenes unfold, giving the whole thing a very written feeling. The film captures, very strongly, the feeling of place in the streets and apartments of Riyadh, but it's not so great at placing human beings in those places. Having a lead with Mohammed's presence and ease in front of the camera does a lot to erase that problem; so does the lovely location photography by Lutz Reitemeier, and the bright, culturally indeterminate score by Max Richter. I wouldn't go so far as to call any part of Wadjda bad; there are parts that are distinctly limited, by virtue of the production's own limitations, or the rhetorical needs of the story. But the heart of it is passionate and breezy, able to treat highly consequential matters with a light, entertaining touch. With al-Mansour currently completing her British-made second feature, I eagerly look forward to seeing what she can do when given a freer hand to exercise that light touch.

The second-most interesting thing about the 2012 film Wadjda is that it the first movie shot, in its entirety, in Saudi Arabia. The most interesting thing is that it was the first feature film directed by a Saudi woman. Let's be clear, that's not a way of slighting the rest of the film - those are both very distinctive achievements, enough to make Wadjda one of the most singularly groundbreaking movies of the 2010s.

The film hiding beneath those milestones is certainly not groundbreaking. Writer-director Haifaa al-Mansour by her admission took inspiration from Vittorio De Sica's 1948 Bicycle Thieves, the film that codified Italian Neorealism as a major artistic force (Wadjda even includes, as a central plot element, a bicycle). And neo-neorealism, over the next several decades, has become the de facto style for socially-conscious filmmakers in emerging and established film industries alike, using the raw material of the real world to tell stories of everyday people. Wadjda makes no effort at all to break from this tendency, though it's hard to fault it: it is socially conscious, after all, deeply concerned with real life and the real world, and especially with the way that women are so horribly subjugated within it.

It's not a polemic, though, but a light little dramedy about a precocious child (another major borrowing from Bicycle Thieves), who finds herself unexpectedly and unhappily intersecting with her country's nastily restrictive treatment of its female citizens. 10-year-old Wadjda (Waad Mohammed), a resident of Riyadh, wants a bike. That's pretty much the beginning and end of it. She wants a bike because her best friend Abdullah (Abdullrahman Al Gohani) already has a bike, and he really wants to race with her, and she wants the same. What neither child has quite grasped, being just young enough that the concerns of adult society are still a strange & ridiculous concept, is that in Saudi Arabia, riding bikes is on the very long list of behaviors considered unacceptable for women. Wadjda's mother (Reem Abdullah) therefore refuses to buy one (she's concerned that the bicycle seat will destroy her daughter's hymen), and Wadjda's father (Sultan Al Assaf) barely seems to care that he even has a daughter, living far apart from his family, as he toys with the idea of taking on a second wife.

And so begins a series of what I can only think to call "shenanigans", as Wadjda tries to scrape up the 800 riyals to buy the bike her own damn self. This causes no small amount of angst and anguish for the adults around her, until she eventually throws herself into studying the Qur'an, surely a sign of her decision to abandon this folly and lean to be a proper Saudi young woman. Or because she's entered a competition based on a knowledge of the Qur'an, with a top prize of 1000 riyals.

It's the last bit that speaks to the spiky sense of humor that Wadjda displays throughout, and which is, I think, the primary reason why it doesn't feel like more of a harangue By all means, the script doesn't shy away from layering its themes and messages on pretty thickly: while the children are treated as naïve innocents, simply trying to go about the business of having fun, the adults are all more or less immediately slotted into obvious, schematic roles, clearly delineating Which Part Of Society They Represent. And the plot involves Wadjda growing aware of the social structure around her, which sees her as bound to an extraordinarily narrow range of possible behaviors, and which views even mild expressions of personal flair as something dubious and wrong-headed. Al-Mansour very clearly has a lesson she wants to teach us about the way women suffer in Saudi Arabia (movie theaters have not existed in that country since the 1980s, and there is only a limited cinema culture; Wadjda was almost certainly designed primarily for export), and leave absolutely no room for missing that lesson.

Still, there's no real value in a sober, grim-faced sociology lesson that's unbearable to watch, and so it turns out that Wadjda is, rather surprisingly, a substantially fun movie. This has everything to do with its star, first-time (and only time) actor Mohammed. Going all the way back to the very dawn of neorealism, Shoeshine, casting child non-actors has been a fairly easy way to guarantee a certain level of adorable appeal for a project; even when things are going horribly for all concerned, the naturalness and lack of self-consciousness that obtains from letting a kid be a kid on camera has done a lot of good for a lot of movies. There's more to Wadjda, and Wadjda, than just plugging a child into a script and letting the magic happen. Mohammed has a terrific ability to project a sense of wary intelligence, figuring out more than the adults around her want her to, and also backing off on what she reveals to them; she's a cunning and thoughtful figure, not a thoughtlessly innocent one, and watching her puts us in the role of silent co-conspirator against the entire edifice of Saudi culture. She's the cool friend who's a little bit more rebellious than we'd ever dare to be, and watching her hack her way through the conflicts facing her is delightful and invigorating, on top of the feeling of righteousness it entails.

Wadjda herself is the secret ingredient that makes the film click so neatly. It's a perfectly satisfactory piece of filmmaking, though hampered by the rule requiring al-Mansour to sit in a van during the exterior scenes - of which there are many - communicating with the cast and crew (mostly imported from Germany) via walkie-talkies. The result is a certain brittleness in how the scenes unfold, giving the whole thing a very written feeling. The film captures, very strongly, the feeling of place in the streets and apartments of Riyadh, but it's not so great at placing human beings in those places. Having a lead with Mohammed's presence and ease in front of the camera does a lot to erase that problem; so does the lovely location photography by Lutz Reitemeier, and the bright, culturally indeterminate score by Max Richter. I wouldn't go so far as to call any part of Wadjda bad; there are parts that are distinctly limited, by virtue of the production's own limitations, or the rhetorical needs of the story. But the heart of it is passionate and breezy, able to treat highly consequential matters with a light, entertaining touch. With al-Mansour currently completing her British-made second feature, I eagerly look forward to seeing what she can do when given a freer hand to exercise that light touch.