Henry: Portrait of a Killer

I'll tell you what, Collateral Beauty only wishes it could Collateral Beauty as well as The Book of Henry does. This summer's entry in the "uplifting sentimental treacle made by people who learned about humanity by studying our robots" genre has, like that film, a plot swerve so unbelievably apeshit that I cannot imagine how even the most craven, cynical, cocaine-wracked executive would imagine that it could possibly work. Even worse, because... well, I'd rather not talk about what happens in The Book of Henry. It is a film that deserves to be seen cold, though even knowing what happens in the middle (but not the end, a whole other mountain of staggering horse crap), I still found myself agape at the belief that any of this would work.

And I do mean any. It's easy, once you've seen the film, to hang on the wild gyrations of its plot, but even without that, this would be a supremely bad movie. The demented twists are merely what makes it so bad that it's worth seeing - but not, for God's sake, in a theater. Wait for Netflix for this shit - instead of so bad that you despair for the future of character-driven cinema. Because these are not characters, these are... these are...

Alright. So Henry Carpenter (Jaeden Lieberher) is 11 years old, and he is a genius. "Genius" is underselling it. He can predict ever little swerve and swoop in the stock market so accurately that he's managed to bring his single mother's waitressing paychecks up to a checking account worth $650,000, and a stock portfolio worth substantially more. In his spare time, he has picked up a working knowledge of medical science sufficient for him to glance at an MRI for a few seconds and then discuss a treatment regimen with a gobsmacked doctor. For fun, he plots out convoluted schemes for committing the perfect murder, with the hopes of someday assassinating his next-door neighbor, Police Commissioner Glenn Sickelman (Dean Norris).

That's not even close to being the twist. That's what you can pick up just from half-attending to the film's trailer. So here we have a pint-sized Übermensch, gravely concluding that vigilante justice is the only corrective to the sphere of corruption protecting Sickleman, who is at least beating his stepdaughter, Henry's classmate Christina (Maddie Ziegler), and likely worse - the film is appallingly coy on this point, showily coy, even. But then, this is a film in which watching Christina dance relatively anonymous ballet moves gives an adult the flash of insight that the girl's being abused, so perhaps it just doesn't have a clue what "coy" means.

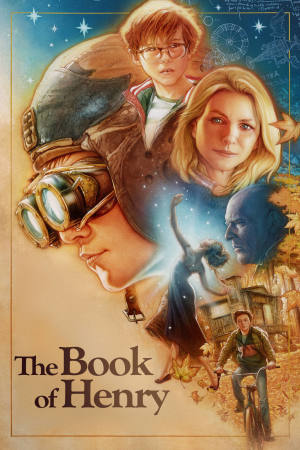

So far, so good: Tween Batman, right? Right, except that the whole entire movie, right up to the Drew Struzan-aping poster, has the treacly vibe of an '80s Amblin movie for the whole family. Michael Giacchino's score laughs and sparkles with the joy of a childhood afternoon, John Schwartzman's cinematography bathes everything in that perfect sun-dappled Norman Rockwell aura that is the exact thing you hire John Schwartzman to do, Colin Trevorrow directs with a wide-eyed attention to the specialness of childhood, filtering as much of the film as he can manage through Henry and his awestruck younger brother Peter (Jacob Tremblay). It's a Steven Spielberg homage as complete as anything in J.J. Abram's wet dreams, so cozily retrograde in every element of its aesthetics that it's actively shocking when something like an iPad wanders into frame. And it is, I want to reiterate, about an 11-year-old boy planning to murder a molester because of his ruthlessly purefied ethical code.

I'm sorry, an 11-year-old boy planning to goad his mother into said murder. The boys' mom, Susan (Naomi Watts), is comfortable in the life her son has set up, being a tender and loving mom to Peter, and not hiding her amazement at Henry whatsoever, nor questioning his authority, nor following-up any attempt to assert mom-hood over him. I mean, eventually she does. That's the entire arc of the film, sort of: Susan's laborious road to realising that, in fact, even the world's smartest 11-year-old is still an 11-year-old, and his notions should not necessarily be followed like the Word of God. Though given the breadth and depth of Henry's wisdom, divinity might be the only reasonable explanation for what the hell all is going on. The nature of how she makes this breakthrough, and how she expresses it, is such that it might have been better for all concerned if she hadn't bothered.

There are, I am sure, ways of making this work. Just by altering the tone, even; it would require only a slight push to Gregg Hurwitz's screenplay, exactly as written, for this to be a black comedy. The characters are already caricatured enough for that: Susan is dumb as hell, and Henry is a lifeless robot, a clichéd idea of what "super smart kid" looks like that goes wildly far off the mark. That's really where this falls apart completely, I think: the characters. I mean, we'll buy a hell of a lot if the characterisation is there, right? Perhaps not this. But there's no denying that even without the ridiculous story, these are a whole lot of badly manhandled characters. There is, just to pick one thing somewhat at random, the whole matter of Christina: the character whose suffering is central to everything else in the plot, and just about the least-developed character in the whole film, defined entirely by saggy eyelids and limp bangs. We learn more about sexy doctor David Daniels (Lee Pace), and his mystifyingly poor choice of timing when it comes to flirting; we learn more about brassy waitress Sheila (Sarah Silverman, badly channeling Jennifer Tilly), and her crippling alcoholism that the the film forgets about like a small baby being distracted by jingling keys. And neither of these characters is exactly a prize of screenwriting; at one point, Hurtwitz committed to paper, and everybody else followed along happily, a scene in which Sheila sadly kisses Henry on the lips, a moment that might be sweetly melancholic if she weren't a worn-out alcoholic, and he an emotionless automaton. Oh, and eleven fucking years old.

Other than Peter - and, somewhat distressingly, the wretch Glenn - not a solitary character in the movie behaves in a way that slightly mimics humanity, and this is indeed baked into the very meat of the film. What on earth must it be like to be the mother of such a singular child as Henry? Where does his gift come from? What are the challenges of parenting such a being? Don't ask Susan, she's too busy playing Gears of War and letting her preteen son manage her bills. There's an entire movie sitting in plain sight just in the backstory of The Book of Henry, and nobody involved seemed to notice. So we just get a lot of utterly inexplicable choices by utterly inexplicable people, and it's all treated with delicately saccharine sentimentality, like all of this is normal, somehow. Managing the characters isn't the film's strong suit, nor is managing tone - if I can hazard near to spoiler territory, the film intercuts a soooo-cuuuuute elementary school talent show with stalking scenes involving military-grade weaponry, and you can see exactly what Trevorrow and Hurwitz thought they were up to (Hitchcockian tension through irony), but Jesus, do they not get anywhere close - nor is simply presenting basic coherent plot details, by the final 20 minutes of the movie.

Watts gets the worst of this, by far: she has the least-possible character (the film simultaneously treats Susan as dysfunctionally idiotic and as a cool mom, and roots for her nonstop while obviously doubting that she could even tie her shoes without help), and the only thing in the film resembling an emotional arc. It's depressing to watch; her career hasn't exactly been at its high point, but she deserves more than this. Actually, I maybe overstate my case. Henry might be a more impossible character: a smug, rude sociopath that we're supposed to find appealing, wise, and righteous. He is the absolute worst kind of child-written-by-adults character, and everything about him severely misjudges the capacity for the tween protagonist of a warm-and-fuzzy snapshot of suburban Americana to also be a Sherlock Holmes-level mastermind and emotional black hole. Change Henry, and The Book of Henry might actually work; but then, change Henry, and The Book of Henry would need to be reconceived from top to bottom, leaving no plot detail in place.

And other than robbing us of what's sure to be 2017's best "can you believe this fucking shit?" so-bad-it's-great movie, I can think of no downside to scrapping the whole damn thing and walking away.

And I do mean any. It's easy, once you've seen the film, to hang on the wild gyrations of its plot, but even without that, this would be a supremely bad movie. The demented twists are merely what makes it so bad that it's worth seeing - but not, for God's sake, in a theater. Wait for Netflix for this shit - instead of so bad that you despair for the future of character-driven cinema. Because these are not characters, these are... these are...

Alright. So Henry Carpenter (Jaeden Lieberher) is 11 years old, and he is a genius. "Genius" is underselling it. He can predict ever little swerve and swoop in the stock market so accurately that he's managed to bring his single mother's waitressing paychecks up to a checking account worth $650,000, and a stock portfolio worth substantially more. In his spare time, he has picked up a working knowledge of medical science sufficient for him to glance at an MRI for a few seconds and then discuss a treatment regimen with a gobsmacked doctor. For fun, he plots out convoluted schemes for committing the perfect murder, with the hopes of someday assassinating his next-door neighbor, Police Commissioner Glenn Sickelman (Dean Norris).

That's not even close to being the twist. That's what you can pick up just from half-attending to the film's trailer. So here we have a pint-sized Übermensch, gravely concluding that vigilante justice is the only corrective to the sphere of corruption protecting Sickleman, who is at least beating his stepdaughter, Henry's classmate Christina (Maddie Ziegler), and likely worse - the film is appallingly coy on this point, showily coy, even. But then, this is a film in which watching Christina dance relatively anonymous ballet moves gives an adult the flash of insight that the girl's being abused, so perhaps it just doesn't have a clue what "coy" means.

So far, so good: Tween Batman, right? Right, except that the whole entire movie, right up to the Drew Struzan-aping poster, has the treacly vibe of an '80s Amblin movie for the whole family. Michael Giacchino's score laughs and sparkles with the joy of a childhood afternoon, John Schwartzman's cinematography bathes everything in that perfect sun-dappled Norman Rockwell aura that is the exact thing you hire John Schwartzman to do, Colin Trevorrow directs with a wide-eyed attention to the specialness of childhood, filtering as much of the film as he can manage through Henry and his awestruck younger brother Peter (Jacob Tremblay). It's a Steven Spielberg homage as complete as anything in J.J. Abram's wet dreams, so cozily retrograde in every element of its aesthetics that it's actively shocking when something like an iPad wanders into frame. And it is, I want to reiterate, about an 11-year-old boy planning to murder a molester because of his ruthlessly purefied ethical code.

I'm sorry, an 11-year-old boy planning to goad his mother into said murder. The boys' mom, Susan (Naomi Watts), is comfortable in the life her son has set up, being a tender and loving mom to Peter, and not hiding her amazement at Henry whatsoever, nor questioning his authority, nor following-up any attempt to assert mom-hood over him. I mean, eventually she does. That's the entire arc of the film, sort of: Susan's laborious road to realising that, in fact, even the world's smartest 11-year-old is still an 11-year-old, and his notions should not necessarily be followed like the Word of God. Though given the breadth and depth of Henry's wisdom, divinity might be the only reasonable explanation for what the hell all is going on. The nature of how she makes this breakthrough, and how she expresses it, is such that it might have been better for all concerned if she hadn't bothered.

There are, I am sure, ways of making this work. Just by altering the tone, even; it would require only a slight push to Gregg Hurwitz's screenplay, exactly as written, for this to be a black comedy. The characters are already caricatured enough for that: Susan is dumb as hell, and Henry is a lifeless robot, a clichéd idea of what "super smart kid" looks like that goes wildly far off the mark. That's really where this falls apart completely, I think: the characters. I mean, we'll buy a hell of a lot if the characterisation is there, right? Perhaps not this. But there's no denying that even without the ridiculous story, these are a whole lot of badly manhandled characters. There is, just to pick one thing somewhat at random, the whole matter of Christina: the character whose suffering is central to everything else in the plot, and just about the least-developed character in the whole film, defined entirely by saggy eyelids and limp bangs. We learn more about sexy doctor David Daniels (Lee Pace), and his mystifyingly poor choice of timing when it comes to flirting; we learn more about brassy waitress Sheila (Sarah Silverman, badly channeling Jennifer Tilly), and her crippling alcoholism that the the film forgets about like a small baby being distracted by jingling keys. And neither of these characters is exactly a prize of screenwriting; at one point, Hurtwitz committed to paper, and everybody else followed along happily, a scene in which Sheila sadly kisses Henry on the lips, a moment that might be sweetly melancholic if she weren't a worn-out alcoholic, and he an emotionless automaton. Oh, and eleven fucking years old.

Other than Peter - and, somewhat distressingly, the wretch Glenn - not a solitary character in the movie behaves in a way that slightly mimics humanity, and this is indeed baked into the very meat of the film. What on earth must it be like to be the mother of such a singular child as Henry? Where does his gift come from? What are the challenges of parenting such a being? Don't ask Susan, she's too busy playing Gears of War and letting her preteen son manage her bills. There's an entire movie sitting in plain sight just in the backstory of The Book of Henry, and nobody involved seemed to notice. So we just get a lot of utterly inexplicable choices by utterly inexplicable people, and it's all treated with delicately saccharine sentimentality, like all of this is normal, somehow. Managing the characters isn't the film's strong suit, nor is managing tone - if I can hazard near to spoiler territory, the film intercuts a soooo-cuuuuute elementary school talent show with stalking scenes involving military-grade weaponry, and you can see exactly what Trevorrow and Hurwitz thought they were up to (Hitchcockian tension through irony), but Jesus, do they not get anywhere close - nor is simply presenting basic coherent plot details, by the final 20 minutes of the movie.

Watts gets the worst of this, by far: she has the least-possible character (the film simultaneously treats Susan as dysfunctionally idiotic and as a cool mom, and roots for her nonstop while obviously doubting that she could even tie her shoes without help), and the only thing in the film resembling an emotional arc. It's depressing to watch; her career hasn't exactly been at its high point, but she deserves more than this. Actually, I maybe overstate my case. Henry might be a more impossible character: a smug, rude sociopath that we're supposed to find appealing, wise, and righteous. He is the absolute worst kind of child-written-by-adults character, and everything about him severely misjudges the capacity for the tween protagonist of a warm-and-fuzzy snapshot of suburban Americana to also be a Sherlock Holmes-level mastermind and emotional black hole. Change Henry, and The Book of Henry might actually work; but then, change Henry, and The Book of Henry would need to be reconceived from top to bottom, leaving no plot detail in place.

And other than robbing us of what's sure to be 2017's best "can you believe this fucking shit?" so-bad-it's-great movie, I can think of no downside to scrapping the whole damn thing and walking away.