Blockbuster History Presents Arthuriana Week: The Cartoon (No, the Other Cartoon)

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: director Guy Ritchie's King Arthur: Legend of the Sword reminds us of the wide range of approaches that filmmakers have taken towards staging the Matter of Britain across the decades. It gives me great pleasure to spend a full week delving into some of the many other flavors of King Arthur films that have preceded Ritchie's contemporary stab at the material.

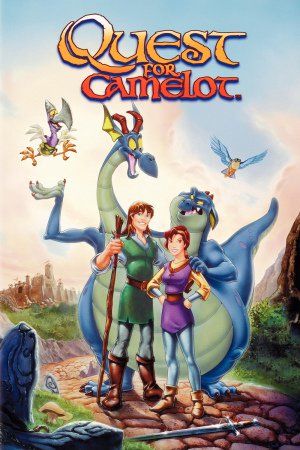

We must say this of Quest for Camelot, it's alarmingly comprehensive: if there's something that traditionally-animated family movies were doing in the 1990s, and it was terrible, you can bet that it shows up somewhere in the 1998 film's haggard 86 minutes. Cut that down to 77 minutes if you don't stick around for the credits, and that would be a shame, since you'd then miss out on no fewer than three reprises of some of the anodyne ballads that make up the film's soundtrack.

Anyway, yes, the 1990s, maybe the single most interesting period (not the same as "good") in the history of American animation. The triumphant artistic - and much more to the point, financial - resurrection of Walt Disney Feature Animation at the end of the 1980s with The Little Mermaid, and the increasing box office success of all of its films up to the record-setting performance of The Lion King in 1994, proved to be a call to arms. For the first time in the history of American cinema, there was a concerted effort by multiple different companies to muscle into Disney's territory, and so the decade is pockmarked with little efforts which almost uniformly came to naught. And as traditional animation was thus puking itself to death, Toy Story ever-so-casually up-ended the entire marketplace and redefined what "animation" even referred to. Meanwhile, The Simpsons was busily making television a safe home for snappy, adult-focused cartooning, and that is where 2-D animation has cozily lived ever since, at least as far as the American industry cares.

So anyway, a wild time, very transformational, lots of interesting things and awful things jostling around, and Quest for Camelot managed to get all of the awful things and none of the interesting ones. The film is part of Warner Bros' persistent effort to get into the theatrical animation game, some three decades after a much different incarnation of the studio killed of its legendary animation division and the iconic Looney Tunes/Merry Melodies series of short cartoons. For four consecutive years, Warner's released some kind of animated project: Space Jam in 1996, the adorable Cats Don't Dance in 1997. The latter wasn't an in-house production; it was the last work of the short-lived Turner Feature Animation, released by Warner Bros. in the wake of the great Time Warner merger of 1996. Following its completion, Turner Feature Animation and Warner Feature Animation combined forces under the latter name, and as Cats Don't Dance was buried in a pauper's grave by a virtually non-existent marketing campaign (despite solid reviews and rapturous praise within the animation industry), the newly bulked-up studio flung itself into Quest for Camelot. When the film ended up tanking, Warner's lost interest in animated features for the most part, and dug another pauper's grave for The Iron Giant, released in 1999 to outright rhapsodic reviews, and it wouldn't be until 15 years later with The Lego Movie that the studio finally decided to take another crack at the whole "animated feature" thing.

All of which is largely besides the point, and the point is that Quest for Camelot is dogshit. It copies the Disney Renaissance narrative model in every detail, without understanding why that formula works: this is particularly horrible for a film coming almost exactly in the middle between 20th Century Fox's Anastasia (directed by Disney defector Don Bluth) and DreamWorks's The Prince of Egypt (produced by Disney defector Jeffrey Katzenberg), both of which also copy Disney in virtually every way but do it extremely well. Both of those movies are also pretty well-made, if not quite at the unassailable technical level of Mulan-era Disney. Quest for Camelot is very much not that good, which is even actually a little surprising: the exact same studio would be capable of the sublime The Iron Giant only a little more than a year later, and while I hate Space Jam very much, it's certainly not because of the technical quality of its animation. Hell, even Cats Don't Dance looks pretty wonderful, considering the lack of real budgetary resources.

But nope, Quest for Camelot simply can't keep up. It boasts some profoundly ugly character designs, of virtually every human character: they all have blocky rectangular faces with huge lantern jaws, even the women, and noses like lumps of clay. The villain is animated with a series of facial jerks and twitches and eye rolls that are, I suppose, meant to imply how psychotic he is all the time, but which are just massively off-putting. Everybody else moves in stiff lines, like unusually well-colored versions of the old Hanna-Barbera TV characters (and wouldn't you know: Hanna-Barbera eventually turned into Turner Feature Animation). In one aerial shot, we see people dancing in circle shapes, and where the circles intersect, characters move straight through each other. It's hideous and awful and sad, and it's definitely not the worst thing about the movie. I mean, at least it's mostly functional as a work of animation. It was made for proper money and by people trained in their craft (albeit people who were being crushed to death by busybody executives).

The worst thing about the movie is a tie, I'd say, between the story, the humor, the music, and the characters, so I guess we might sum it up as "everything other than the animation". We arrive in medieval England ten years after the young King Arthur (Pierce Brosnan) pulled the sword Excalibur from a stone - in Stonehenge, apparently - and established the stronghold of Camelot. To celebrate the anniversary, Arthur has gathered all the knights of the Round Table to sing "United We Stand", the first of Carole Bayer Sager & David Foster's seven original songs, and the one that feels the most like a Broadway number. An insipid one, but in the face of the equally insipid ballads and power ballads to come (and one very weird villain number), I'll take what I can get. Arthur's celebration is cut short, sadly when the fidgety, overtly evil knight Ruber (Gary Oldman) announces that this is all bullshit and he wants to kill the king. Ruber? God almighty, even First Knight at least took its villain's name (a villain with very nearly identical motivations to Ruber) from the actual Arthur legends. Anyway, Ruber's plan is foiled by Lionel (Gabriel Byrne) - Lionel? - a knight who sacrifices himself to save the king. This does mean, sadly, that Lionel leaves behind a wife, Juliana (Jane Seymour), and a brave daughter, Kayley (Sarah Rayne as a child, Jessalyn Gilsig as a young woman, and sung by Andrea Corr, clearly to get all those kids who were huge The Corrs fans glued to their seats), who wants nothing more than to be a knight in Camelot.

Another ten years go by, and Ruber launches his second attack, sending a griffin (Broncon Pinchot) to steal Excalibur. A strangely antagonistic falcon manages to force the griffin into dropping the sword in a thatch of sentient thorn bushes, or something, and from there springs a tale. See, the first thing Ruber does after the sword goes missing is to kidnap Juliana, whom he knows his is his ticket into Camelot, and also to use a magic potion to transform his lackeys into weapon-human hybrids. He also creates a rooster with the head of an axe. This rooster, which gains the power of human speech in the process (and the voice of annoying sitcom star Jaleel White), was introduced in a series of short scenes where he tries to hit on the hens in Juliana and Kayley's farmyard, but keeps getting thwarted by his big, angry hen wife. If any solitary thing in Quest for Camelot managed to scrape through the wall of despairing mediocrity to really make me sit up and notice, and ask in a plaintive tone, "what the hell?", it was that subplot.

The point is, Kayley has to find Excalibur before Ruber does, and she does this with the help of Garrett (Cary Elwes), a young blind man who wanted to be a knight until an accident where a horse apparently stepped on his face, which seems like it might have more pronounced side-effects than blindness. Also helping out are that magical falcon, Ayden (squawked by Frank Welker), the trusted pet of the wizard Merlin (Sir John Gielgud), and a two-headed dragon named Devon (Eric Idle) and Cornwall (Don Rickles).This all follows the only plot it ever could - one that has very little in common with Vera Chapman's book The King's Damosel, its official source - with Kayley proving to be plucky and resourceful, alongside the plucky and resourceful Garrett. Devon and Cornwall are resourceful, but perhaps not "plucky", but they do learn to love each other, and that's sufficient for the kiddie movie boilerplate. It's not the familiarity that rankles, though, but the colossal ineptitude. Everything throughout Quest for Camelot is done in a half-assed, awkward way, starting with the thinly-sketched characters, and the vague performances (Oldman is the only cast member who makes a strong impression, and it's definitely not for good reasons).

Not that the actors can be blamed, necessarily. The script is stitched together in a clunky way, with no real cause-and-effect chain between most of what happens. The plot basically disappears for a huge chunk of the middle, when it's just several adventure slapstick bits and dreadful musical numbers. Such dreadful musical numbers. "The Prayer", an Oscar-nominee, is decent enough, though Céline Dion is a wildly unconvincing singing double for Jane Seymour. The rest are all some shade of terrible, mostly because they are banal; but in the case of the dragons' comic duet, because it has a robotic, monotonous rhythm, and requires us to listen to Don Rickles's singing voice.

Anyway, there's just nothing pleasurable to be scraped out from any of this. Some of the creature designs are fun; the griffin, particularly, is occasionally a striking example of the dramatic dark mode favored by Don Bluth. The humans, though, are powerfully unappealing visually, and combined with the trite lessons and one-note personalities, it's hard to regard any of them with anything other than loathing. The comedy is pathetically anachronistic, doing very little other than using modern slang incongruously and not having punchlines. And the film boasts the single worst marriage of traditional animation with CGI that I've ever seen, in the form of a giant stone ogre that was nowhere near ready for audiences to see it, even before the rest of the characters were badly pasted atop it.

Also, the ogre farts a fart so powerful that it shoots Ruber into a cave wall like a bullet from a gun. Because really, why wouldn't it?

We must say this of Quest for Camelot, it's alarmingly comprehensive: if there's something that traditionally-animated family movies were doing in the 1990s, and it was terrible, you can bet that it shows up somewhere in the 1998 film's haggard 86 minutes. Cut that down to 77 minutes if you don't stick around for the credits, and that would be a shame, since you'd then miss out on no fewer than three reprises of some of the anodyne ballads that make up the film's soundtrack.

Anyway, yes, the 1990s, maybe the single most interesting period (not the same as "good") in the history of American animation. The triumphant artistic - and much more to the point, financial - resurrection of Walt Disney Feature Animation at the end of the 1980s with The Little Mermaid, and the increasing box office success of all of its films up to the record-setting performance of The Lion King in 1994, proved to be a call to arms. For the first time in the history of American cinema, there was a concerted effort by multiple different companies to muscle into Disney's territory, and so the decade is pockmarked with little efforts which almost uniformly came to naught. And as traditional animation was thus puking itself to death, Toy Story ever-so-casually up-ended the entire marketplace and redefined what "animation" even referred to. Meanwhile, The Simpsons was busily making television a safe home for snappy, adult-focused cartooning, and that is where 2-D animation has cozily lived ever since, at least as far as the American industry cares.

So anyway, a wild time, very transformational, lots of interesting things and awful things jostling around, and Quest for Camelot managed to get all of the awful things and none of the interesting ones. The film is part of Warner Bros' persistent effort to get into the theatrical animation game, some three decades after a much different incarnation of the studio killed of its legendary animation division and the iconic Looney Tunes/Merry Melodies series of short cartoons. For four consecutive years, Warner's released some kind of animated project: Space Jam in 1996, the adorable Cats Don't Dance in 1997. The latter wasn't an in-house production; it was the last work of the short-lived Turner Feature Animation, released by Warner Bros. in the wake of the great Time Warner merger of 1996. Following its completion, Turner Feature Animation and Warner Feature Animation combined forces under the latter name, and as Cats Don't Dance was buried in a pauper's grave by a virtually non-existent marketing campaign (despite solid reviews and rapturous praise within the animation industry), the newly bulked-up studio flung itself into Quest for Camelot. When the film ended up tanking, Warner's lost interest in animated features for the most part, and dug another pauper's grave for The Iron Giant, released in 1999 to outright rhapsodic reviews, and it wouldn't be until 15 years later with The Lego Movie that the studio finally decided to take another crack at the whole "animated feature" thing.

All of which is largely besides the point, and the point is that Quest for Camelot is dogshit. It copies the Disney Renaissance narrative model in every detail, without understanding why that formula works: this is particularly horrible for a film coming almost exactly in the middle between 20th Century Fox's Anastasia (directed by Disney defector Don Bluth) and DreamWorks's The Prince of Egypt (produced by Disney defector Jeffrey Katzenberg), both of which also copy Disney in virtually every way but do it extremely well. Both of those movies are also pretty well-made, if not quite at the unassailable technical level of Mulan-era Disney. Quest for Camelot is very much not that good, which is even actually a little surprising: the exact same studio would be capable of the sublime The Iron Giant only a little more than a year later, and while I hate Space Jam very much, it's certainly not because of the technical quality of its animation. Hell, even Cats Don't Dance looks pretty wonderful, considering the lack of real budgetary resources.

But nope, Quest for Camelot simply can't keep up. It boasts some profoundly ugly character designs, of virtually every human character: they all have blocky rectangular faces with huge lantern jaws, even the women, and noses like lumps of clay. The villain is animated with a series of facial jerks and twitches and eye rolls that are, I suppose, meant to imply how psychotic he is all the time, but which are just massively off-putting. Everybody else moves in stiff lines, like unusually well-colored versions of the old Hanna-Barbera TV characters (and wouldn't you know: Hanna-Barbera eventually turned into Turner Feature Animation). In one aerial shot, we see people dancing in circle shapes, and where the circles intersect, characters move straight through each other. It's hideous and awful and sad, and it's definitely not the worst thing about the movie. I mean, at least it's mostly functional as a work of animation. It was made for proper money and by people trained in their craft (albeit people who were being crushed to death by busybody executives).

The worst thing about the movie is a tie, I'd say, between the story, the humor, the music, and the characters, so I guess we might sum it up as "everything other than the animation". We arrive in medieval England ten years after the young King Arthur (Pierce Brosnan) pulled the sword Excalibur from a stone - in Stonehenge, apparently - and established the stronghold of Camelot. To celebrate the anniversary, Arthur has gathered all the knights of the Round Table to sing "United We Stand", the first of Carole Bayer Sager & David Foster's seven original songs, and the one that feels the most like a Broadway number. An insipid one, but in the face of the equally insipid ballads and power ballads to come (and one very weird villain number), I'll take what I can get. Arthur's celebration is cut short, sadly when the fidgety, overtly evil knight Ruber (Gary Oldman) announces that this is all bullshit and he wants to kill the king. Ruber? God almighty, even First Knight at least took its villain's name (a villain with very nearly identical motivations to Ruber) from the actual Arthur legends. Anyway, Ruber's plan is foiled by Lionel (Gabriel Byrne) - Lionel? - a knight who sacrifices himself to save the king. This does mean, sadly, that Lionel leaves behind a wife, Juliana (Jane Seymour), and a brave daughter, Kayley (Sarah Rayne as a child, Jessalyn Gilsig as a young woman, and sung by Andrea Corr, clearly to get all those kids who were huge The Corrs fans glued to their seats), who wants nothing more than to be a knight in Camelot.

Another ten years go by, and Ruber launches his second attack, sending a griffin (Broncon Pinchot) to steal Excalibur. A strangely antagonistic falcon manages to force the griffin into dropping the sword in a thatch of sentient thorn bushes, or something, and from there springs a tale. See, the first thing Ruber does after the sword goes missing is to kidnap Juliana, whom he knows his is his ticket into Camelot, and also to use a magic potion to transform his lackeys into weapon-human hybrids. He also creates a rooster with the head of an axe. This rooster, which gains the power of human speech in the process (and the voice of annoying sitcom star Jaleel White), was introduced in a series of short scenes where he tries to hit on the hens in Juliana and Kayley's farmyard, but keeps getting thwarted by his big, angry hen wife. If any solitary thing in Quest for Camelot managed to scrape through the wall of despairing mediocrity to really make me sit up and notice, and ask in a plaintive tone, "what the hell?", it was that subplot.

The point is, Kayley has to find Excalibur before Ruber does, and she does this with the help of Garrett (Cary Elwes), a young blind man who wanted to be a knight until an accident where a horse apparently stepped on his face, which seems like it might have more pronounced side-effects than blindness. Also helping out are that magical falcon, Ayden (squawked by Frank Welker), the trusted pet of the wizard Merlin (Sir John Gielgud), and a two-headed dragon named Devon (Eric Idle) and Cornwall (Don Rickles).This all follows the only plot it ever could - one that has very little in common with Vera Chapman's book The King's Damosel, its official source - with Kayley proving to be plucky and resourceful, alongside the plucky and resourceful Garrett. Devon and Cornwall are resourceful, but perhaps not "plucky", but they do learn to love each other, and that's sufficient for the kiddie movie boilerplate. It's not the familiarity that rankles, though, but the colossal ineptitude. Everything throughout Quest for Camelot is done in a half-assed, awkward way, starting with the thinly-sketched characters, and the vague performances (Oldman is the only cast member who makes a strong impression, and it's definitely not for good reasons).

Not that the actors can be blamed, necessarily. The script is stitched together in a clunky way, with no real cause-and-effect chain between most of what happens. The plot basically disappears for a huge chunk of the middle, when it's just several adventure slapstick bits and dreadful musical numbers. Such dreadful musical numbers. "The Prayer", an Oscar-nominee, is decent enough, though Céline Dion is a wildly unconvincing singing double for Jane Seymour. The rest are all some shade of terrible, mostly because they are banal; but in the case of the dragons' comic duet, because it has a robotic, monotonous rhythm, and requires us to listen to Don Rickles's singing voice.

Anyway, there's just nothing pleasurable to be scraped out from any of this. Some of the creature designs are fun; the griffin, particularly, is occasionally a striking example of the dramatic dark mode favored by Don Bluth. The humans, though, are powerfully unappealing visually, and combined with the trite lessons and one-note personalities, it's hard to regard any of them with anything other than loathing. The comedy is pathetically anachronistic, doing very little other than using modern slang incongruously and not having punchlines. And the film boasts the single worst marriage of traditional animation with CGI that I've ever seen, in the form of a giant stone ogre that was nowhere near ready for audiences to see it, even before the rest of the characters were badly pasted atop it.

Also, the ogre farts a fart so powerful that it shoots Ruber into a cave wall like a bullet from a gun. Because really, why wouldn't it?