She's so unusual

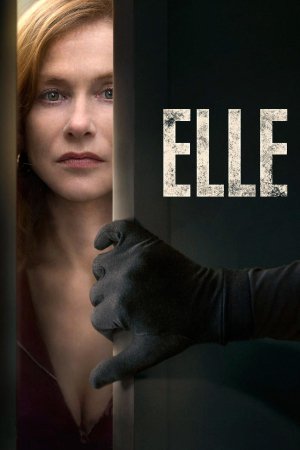

The fact that Elle isn't punishingly unpleasant is maybe the most unpleasant thing about it. One longs for the film to tip fully over into brutal viciousness, so we could be sure that it's got the proper outrage about its sordid subject matter; or for it to go all-in on sleazy exploitation, so we could appreciate it as high trash. Instead, it's 130 minutes of making us feel just horrible about how delectably easy it is to watch this pitch-black comic rape thriller.

In other words, after a ten-year hiatus from making features (and even way back in 2006, Black Book was itself a return from a decently long break), Paul Verhoeven is back. This time, he's teamed up with Isabelle Huppert, which is such a perfect pair - cinema's two greatest provocateurs about demented sexual behavior, together at last! - that I'm a little bit stunned it's never happened before, and that it only barely happened this time. Verhoeven had initially planned to film this adaptation of Philippe Djian's 2012 novel Oh... in the United States, from a screenplay in English by David Birke. But when no anglophone movie star would take a second look at the enormously disturbing screenplay, he switched gears and returned to Djian's own France, where psychologically bent, fearsomely controversial stories that indelicately treat upon delicate matters are much more common than they are in Hollywood. Huppert, for her part, had been interested in the main character from the moment she first read the novel, and pounced on the project as soon as it was retooled (with a translation of Birke's screenplay by Harold Manning).

The film that emerges is a lot of things, most of them nasty, many of them uncomfortably hilarious. Huppert plays Michèle Leblanc, an executive at a video game company, an emotionally unavailable mother, a regretful ex-wife, a resentful daughter, an unfaithful friend, a dirty-minded neighbor, and, as of the film's opening scene, a rape survivor. Taken all together, Michèle is one of the great characters of this or any one of several recent years. She's outwardly unpleasant in most ways, almost a stereotype of sexist assumptions about powerful women, yet with the film yoking itself to her POV and never budging from it for a single frame, we invariably take her side on everything, even when it seems like she's unquestionably in the wrong from any objective outside standpoint. In one of the film's many perverse touches, she is herself offers the most explicit hatred of theoretically empowered in the movie, lashing out against her aging mother Irène (Judith Magre) for taking a much younger stud as a lover, and attacking her son Vincent (Jonas Bloquet) for letting himself be cowed by his strong-willed, promiscuous, pregnant girlfriend Josie (Alice Isaaz). The first time we see her in her guise as an executive, it's as she complains that a female character in the game being raped by the player-controlled demon isn't writhing orgasmically enough, apparently the very next day after she is herself raped. She is a figure of contradictions, you might say.

The film's treatment of sexual assault is astonishingly hard to get a handle on, and I'm not going to succeed in doing so, though it is in most ways the central aspect of the film. After all, the first thing we see about Michèle is the attack. The second, however, is that she seems thoroughly pragmatic and unruffled about it. Annoyed as hell, but... but what? That is, in most ways, the central question of Elle, and the best I've got is that Michèle, a ruthless person used to wielding power against everyone in her life, is thrown for a loop by discovering that she's capable of being hurt. She is quite traumatised by her experience, of course, but it's not the trauma that upsets her - it's the knowledge that she can be traumatised. That she is a feeling person who can be terrified and threatened and made to feel diminished by someone else's actions against her. These are all things that do not fit into her self-narrative, and I think that most of the exorbitantly fucked-up things that transpire over the course of Elle's running time can be read as Michèle's attempt to restore that narrative.

This is absolutely not a nice movie, and if someone were to maintain that it's vile trash for the way it depicts rape, I can't think of a single reasonable counterargument. But being nice, or even being moral, is not the only thing that art can or should do, and Elle is completely absorbing as a character study. Huppert is outlandishly great - I would definitely not want to pick between her performance here or in Things to Come, though this one appears to have the higher degree of difficulty. Michèle is, in all the ways I can think of, the ultimate Isabelle Huppert character: intensely, intimidatingly smart, and raw with carnality, and full of mildly self-deprecating irony, and able to project a facade of complete opacity, only that same opacity ends up letting us understand what's going on inside of her head more than extreme, vivid emotion would. The film's structure does some of Huppert's acting for her; because it opens so repulsively and aggressively, we have absolutely no chance of forgetting what happened to her, and we naturally read that into her behavior. The rape echoes over the whole film, even when Michèle's sardonic wit takes over and turn the thing into a practically Wildean comedy of manners (I'd heard the film was comic; I was nevertheless definitely not prepared to laugh out loud as often or as hard as I did at the idiotic absurdities Michèle has to face and her withering way of dealing with them), and that lends it a sickening feeling, a feeling that we are doing something bad and dirty by enjoying the movie.

That, of course, is the Verhoeven touch, and its present from the very first shot: as we hear the thumps and screams the attack, we find ourselves staring right into the face of an adorably alert cat watching with unnerving interest. It can't help but be amusing - it isn't amusing, but it can't help but be anyway (later on, Michèle scoops the cat up and admonishes "You could have at least scratched him" in her most affectionate "you're such a kitty!" voice - the fact that the character is making light of the attack that way is far less disorienting than the fact that Huppert has a "you're such a kitty!" voice). What's going on here seems to be somewhat the French equivalent of what Verhoeven was doing with his American movies, exaggerating the extremes of the national cinema: our affection for violent entertainment with RoboCop, our giggling prurience about sex with Showgirls, both of them together with Basic Instinct. In Elle's case, that's the French cinema's boundless enthusiasm for portraying fucked-up sexual kinks in dourly lurid tones, usually calculated to make the audience hate themselves for having a libido. And it should be noted that Huppert is no stranger to this genre herself: prior to her annus mirabilis of 2016, my favorite of her performances was in 2001's The Piano Teacher;, a lacerating portrayal of sexual repression manifesting as self-harm that would form quite a joyless but awfully telling double feature with Elle. That film, you see, is by Michael Haneke, who's kind of like the mirror universe Verhoeven: both delight in making savagely provocative films that insult every social norm they can lay their hands on, but Haneke does it with an angry snarl and Verhoeven with a sleazy laugh. And I think that viewing Elle as the sleazy, funny Piano Teacher is kind of the perfect approach.

In both cases, after all, extreme (and extremely unpalatable) sexual masochism is depicted, but neither is "about" sex; they're both about the character of a woman whose tormented past has fundamentally shifted her personality in ways that lead to disturbing behavior , and both women are funneled through Huppert's amazingly restrained expressions and movements. Michèle is more dynamic, complicated, and thoroughly disquieting than Erika Kohut, with a hell of a lot more plot threads to tie into a single character (the relationship between Michèle and any one of her son, mother, ex-husband, business partner, spree killer father, and rapist would be sufficient to power an entire feature, and Huppert gets to do something with all of them); that's part of what makes Elle so hugely compelling. Not least of the character's complexity is that she is so funny, that she is so appealing and attractive in her acidic tongue and faultless reaction shots - Huppert, as should come as no surprise, has note-perfect comic timing - and not, apparently, as a defense mechanism against her horrifying experience, but because she's that good at compartmentalising.

I don't want to over-sell the degree to which this is he Isabelle Huppert Show: it's still ace filmmaking, altogether, especially the editing by Job ter Burg (one of the only members of the predominately French crew to have worked with Verhoeven before), which punches up both the comedy and the tension as Michèle feels increasingly vulnerable; if for nothing but the gut-wrenching suddenness with which flashbacks to the rape interrupt the action, I'd say that Verhoeven and ter Burg had achieved something quite splendid in the cut, and that's only the flashiest editing, not the best. The best is probably the analytical dissection of the room where Michèle hosts a militantly bourgois Christmas dinner, and also where a perfectly-timed snort of derision proved to be just about the funniest thing I saw in a 2016 film. There's also much adore in Stéphane Fontaine's lightly diffuse cinematography, and his way of capturing Christmas lights as something beautiful and tacky, and the production design by Laurent Ott, which surrounds Michèle with windows, an elegant affectation that turns into a literalisation of her feeling of being constantly spied and preyed upon.

It is, however, mostly the Isabelle Huppert Show, and that's just fine. Verhoeven's meticulously deliberate bad taste and discomfiting mélange of brutality and wit might be what makes Elle so disturbingly watchable; Huppert's plunge into the darkness and fortitude of her character make it great cinema. Whatever else is true of Elle, it is a singularly rich character study.

In other words, after a ten-year hiatus from making features (and even way back in 2006, Black Book was itself a return from a decently long break), Paul Verhoeven is back. This time, he's teamed up with Isabelle Huppert, which is such a perfect pair - cinema's two greatest provocateurs about demented sexual behavior, together at last! - that I'm a little bit stunned it's never happened before, and that it only barely happened this time. Verhoeven had initially planned to film this adaptation of Philippe Djian's 2012 novel Oh... in the United States, from a screenplay in English by David Birke. But when no anglophone movie star would take a second look at the enormously disturbing screenplay, he switched gears and returned to Djian's own France, where psychologically bent, fearsomely controversial stories that indelicately treat upon delicate matters are much more common than they are in Hollywood. Huppert, for her part, had been interested in the main character from the moment she first read the novel, and pounced on the project as soon as it was retooled (with a translation of Birke's screenplay by Harold Manning).

The film that emerges is a lot of things, most of them nasty, many of them uncomfortably hilarious. Huppert plays Michèle Leblanc, an executive at a video game company, an emotionally unavailable mother, a regretful ex-wife, a resentful daughter, an unfaithful friend, a dirty-minded neighbor, and, as of the film's opening scene, a rape survivor. Taken all together, Michèle is one of the great characters of this or any one of several recent years. She's outwardly unpleasant in most ways, almost a stereotype of sexist assumptions about powerful women, yet with the film yoking itself to her POV and never budging from it for a single frame, we invariably take her side on everything, even when it seems like she's unquestionably in the wrong from any objective outside standpoint. In one of the film's many perverse touches, she is herself offers the most explicit hatred of theoretically empowered in the movie, lashing out against her aging mother Irène (Judith Magre) for taking a much younger stud as a lover, and attacking her son Vincent (Jonas Bloquet) for letting himself be cowed by his strong-willed, promiscuous, pregnant girlfriend Josie (Alice Isaaz). The first time we see her in her guise as an executive, it's as she complains that a female character in the game being raped by the player-controlled demon isn't writhing orgasmically enough, apparently the very next day after she is herself raped. She is a figure of contradictions, you might say.

The film's treatment of sexual assault is astonishingly hard to get a handle on, and I'm not going to succeed in doing so, though it is in most ways the central aspect of the film. After all, the first thing we see about Michèle is the attack. The second, however, is that she seems thoroughly pragmatic and unruffled about it. Annoyed as hell, but... but what? That is, in most ways, the central question of Elle, and the best I've got is that Michèle, a ruthless person used to wielding power against everyone in her life, is thrown for a loop by discovering that she's capable of being hurt. She is quite traumatised by her experience, of course, but it's not the trauma that upsets her - it's the knowledge that she can be traumatised. That she is a feeling person who can be terrified and threatened and made to feel diminished by someone else's actions against her. These are all things that do not fit into her self-narrative, and I think that most of the exorbitantly fucked-up things that transpire over the course of Elle's running time can be read as Michèle's attempt to restore that narrative.

This is absolutely not a nice movie, and if someone were to maintain that it's vile trash for the way it depicts rape, I can't think of a single reasonable counterargument. But being nice, or even being moral, is not the only thing that art can or should do, and Elle is completely absorbing as a character study. Huppert is outlandishly great - I would definitely not want to pick between her performance here or in Things to Come, though this one appears to have the higher degree of difficulty. Michèle is, in all the ways I can think of, the ultimate Isabelle Huppert character: intensely, intimidatingly smart, and raw with carnality, and full of mildly self-deprecating irony, and able to project a facade of complete opacity, only that same opacity ends up letting us understand what's going on inside of her head more than extreme, vivid emotion would. The film's structure does some of Huppert's acting for her; because it opens so repulsively and aggressively, we have absolutely no chance of forgetting what happened to her, and we naturally read that into her behavior. The rape echoes over the whole film, even when Michèle's sardonic wit takes over and turn the thing into a practically Wildean comedy of manners (I'd heard the film was comic; I was nevertheless definitely not prepared to laugh out loud as often or as hard as I did at the idiotic absurdities Michèle has to face and her withering way of dealing with them), and that lends it a sickening feeling, a feeling that we are doing something bad and dirty by enjoying the movie.

That, of course, is the Verhoeven touch, and its present from the very first shot: as we hear the thumps and screams the attack, we find ourselves staring right into the face of an adorably alert cat watching with unnerving interest. It can't help but be amusing - it isn't amusing, but it can't help but be anyway (later on, Michèle scoops the cat up and admonishes "You could have at least scratched him" in her most affectionate "you're such a kitty!" voice - the fact that the character is making light of the attack that way is far less disorienting than the fact that Huppert has a "you're such a kitty!" voice). What's going on here seems to be somewhat the French equivalent of what Verhoeven was doing with his American movies, exaggerating the extremes of the national cinema: our affection for violent entertainment with RoboCop, our giggling prurience about sex with Showgirls, both of them together with Basic Instinct. In Elle's case, that's the French cinema's boundless enthusiasm for portraying fucked-up sexual kinks in dourly lurid tones, usually calculated to make the audience hate themselves for having a libido. And it should be noted that Huppert is no stranger to this genre herself: prior to her annus mirabilis of 2016, my favorite of her performances was in 2001's The Piano Teacher;, a lacerating portrayal of sexual repression manifesting as self-harm that would form quite a joyless but awfully telling double feature with Elle. That film, you see, is by Michael Haneke, who's kind of like the mirror universe Verhoeven: both delight in making savagely provocative films that insult every social norm they can lay their hands on, but Haneke does it with an angry snarl and Verhoeven with a sleazy laugh. And I think that viewing Elle as the sleazy, funny Piano Teacher is kind of the perfect approach.

In both cases, after all, extreme (and extremely unpalatable) sexual masochism is depicted, but neither is "about" sex; they're both about the character of a woman whose tormented past has fundamentally shifted her personality in ways that lead to disturbing behavior , and both women are funneled through Huppert's amazingly restrained expressions and movements. Michèle is more dynamic, complicated, and thoroughly disquieting than Erika Kohut, with a hell of a lot more plot threads to tie into a single character (the relationship between Michèle and any one of her son, mother, ex-husband, business partner, spree killer father, and rapist would be sufficient to power an entire feature, and Huppert gets to do something with all of them); that's part of what makes Elle so hugely compelling. Not least of the character's complexity is that she is so funny, that she is so appealing and attractive in her acidic tongue and faultless reaction shots - Huppert, as should come as no surprise, has note-perfect comic timing - and not, apparently, as a defense mechanism against her horrifying experience, but because she's that good at compartmentalising.

I don't want to over-sell the degree to which this is he Isabelle Huppert Show: it's still ace filmmaking, altogether, especially the editing by Job ter Burg (one of the only members of the predominately French crew to have worked with Verhoeven before), which punches up both the comedy and the tension as Michèle feels increasingly vulnerable; if for nothing but the gut-wrenching suddenness with which flashbacks to the rape interrupt the action, I'd say that Verhoeven and ter Burg had achieved something quite splendid in the cut, and that's only the flashiest editing, not the best. The best is probably the analytical dissection of the room where Michèle hosts a militantly bourgois Christmas dinner, and also where a perfectly-timed snort of derision proved to be just about the funniest thing I saw in a 2016 film. There's also much adore in Stéphane Fontaine's lightly diffuse cinematography, and his way of capturing Christmas lights as something beautiful and tacky, and the production design by Laurent Ott, which surrounds Michèle with windows, an elegant affectation that turns into a literalisation of her feeling of being constantly spied and preyed upon.

It is, however, mostly the Isabelle Huppert Show, and that's just fine. Verhoeven's meticulously deliberate bad taste and discomfiting mélange of brutality and wit might be what makes Elle so disturbingly watchable; Huppert's plunge into the darkness and fortitude of her character make it great cinema. Whatever else is true of Elle, it is a singularly rich character study.

Categories: french cinema, paul verhoeven, thrillers, tis the season, unfunny comedies