Poetry in motion

Only a director as reliably extraordinary as Jim Jarmusch could make a movie as sensitive and heartbreaking as Paterson and have it feel vaguely disappointing. I cannot speak for any other fans of the director's work, but what I like most about his now twelve narrative features is how the best of them seriously interrogate and challenge the basic assumptions and formulas of narrative storytelling, even in the apparent guise of building a straightforward genre exercise. He happens to be coming off of two films that have done this particularly aggressively: 2009's The Limits of Control (inarguably his "hardest" movie), and 2013's Only Lovers Left Alive (which I greatly underestimated when it was new, and I harbor some hope I'm doing the same thing with Paterson), which makes it all the more upsetting that Paterson isn't just more conventional than that pair of uniquely unconventional experiments; it seems possible to me that this is the most conventional feature Jarmusch has ever made.

That's absolutely not to say that he's "sold out" or some damn thing, and by any reasonably objective standard, Paterson is a glory: a striking character study written with intelligence, performed with uniquely subtle sensitivity, and making outstanding use of a particular location by drawing upon both its geography and cultural makeup. That location being Paterson, New Jersey, a city of some significance not just historically, but artistically: long before Jarmusch set his sights on it, poet William Carlos Williams wrote his own Paterson, teasing out the city as a representation of all America. Jarmusch's Paterson doesn't have nearly such airy intentions: instead, it's a deep dive into the life of one man over one week. His name is also Paterson, and he's a bus driver played by Adam Driver, which is a nimble bit of doubling that was almost certainly a coincidence, but ties in nicely with everything else that the movie is doing.

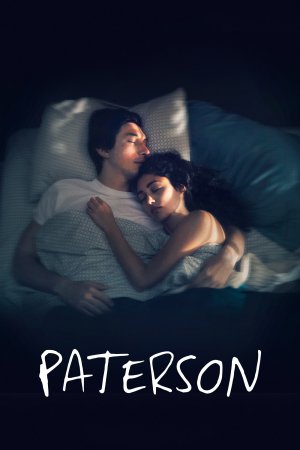

For as it turns out, Jarmusch's Paterson is a descendant of Williams's Paterson in more than just setting. As has been done a few times, but not recently that I can think of and not in such a thoroughgoing way, the film is structured according to the principles of poetry, not narrative. Which is to say, it's long on imagery and longer on what we might call rhetorical devices, including repetition and parallelism - the basic unit of Paterson-the-movie is the single day, always beginning with the same shot of Paterson-the-man and his girlfriend Laura (Golshifteh Farahani) lying in bed, and generally proceeding through the same order of events, though the specific details are always a touch different. The exact cadence of his conversations with his supervisor Donny (Rizwan Manji) shifts, he eavesdrops on a different conversation between passengers on his bus, he encounters different sets of twins, or doppelgängers, or whatever we want to make of the film's extensive population of individuals who precisely resemble each other. Perhaps we're not even supposed to assume that these people and conversations and encounters all literally exist, but that they're simply extensions of Paterson's brain, visual representations of how he thinks about the world. Because he's also a poet, our Paterson, and Paterson is mostly a film about how he thinks about the things he encounters before transforming them into writing.

It would be extremely easy for the film to belabor this, as a Marty-style "the working class has a soul, man" affair. Thank God Almighty that it doesn't. In fact, Jarmusch barely registers that this could be regarded as any kind of surprise at all; it's simply who Paterson is. Driver plays the role with an extremely satisfying lack of fuss or gilded soulfulness, which proves to be a godsend for the movie; with no special pleading that we should regard Paterson as any kind of prophet or philosopher, the film doesn't get tangled up in grandiose statements about what art is or does, how it's made, how it's consumed. Instead, we're invited to regard poetry as an act, rather than a belief system - a miraculously unromantic notion that treats poem-writing with far more dignity than all the movies that have, swooning, sketched it out as a thunderbolt of inspiration. We see Paterson tinker and labor, attempting to reformat his emotional experiences into words, as an act of communication and of self-analysis. Driver's thoughtful, slightly perturbed facial expressions are perfectly attenuated to increase this sense, allowing him the yearning soul of a poet without losing sight of the concrete facts of the town of Paterson, the house and the bed and the amazingly expressive, contemplative bulldog Marvin (posthumous Palme Dog winner Nellie) who lives with Paterson and Laura, and is by any reasonable yardstick the film's third most interesting and well-realised character.

Paterson is, in short, a feature-length exploration of the linkages between routine, unexceptional daily life and the creation of art, and the kind of personality it takes to transform one into the other. It does this incredibly well, not just through its regimented structure but also its equally repetitive and formulaic visuals, which have adopted the status of punctuation marks - never periods, but always semicolons and commas and the like - by the time the film ends. The few dramatically unexceptional events depicted in the film are, in this scheme, like the unexpected bursts of imagery that give a poem its emotional force - the sensual "they were delicions / so sweet / and cold" that forcefully pays off the quotidian "I have eaten / the plums / that were in / the icebox", to use the example of the one William Carlos Williams poem that shows up prominently in the film's script.

The extraordinarily persuasive everyday-ness is so strong, in fact, that it's a crushing disappointment when Jarmusch abandons it on the last two days of his week; without giving away what happens, Paterson very swiftly becomes exactly the story you would predict, with exactly the clichéd crisis that you'd expect this movie was leading up to if it was some hokey, sentimental bullshit about the striving power of the poet's heart in the face of setbacks. I'm not going to go all the way around to "the ending ruins Paterson", especially because the ending is quite good, with a Japanese tourist (Nagase Masatoshi) on hand to return this to the realm of Jarmusch's more characteristically wry absurdism (among other things, the character is an apparent nod back to the director's Mystery Train). It is the climax that almost ruins Paterson, turning it into something trite and obvious and overdone, and along with the handful of dangling concepts and inexplicable moments, it's enough to make a by-all-means very great film feel like it got something small but critical wrong.

That's absolutely not to say that he's "sold out" or some damn thing, and by any reasonably objective standard, Paterson is a glory: a striking character study written with intelligence, performed with uniquely subtle sensitivity, and making outstanding use of a particular location by drawing upon both its geography and cultural makeup. That location being Paterson, New Jersey, a city of some significance not just historically, but artistically: long before Jarmusch set his sights on it, poet William Carlos Williams wrote his own Paterson, teasing out the city as a representation of all America. Jarmusch's Paterson doesn't have nearly such airy intentions: instead, it's a deep dive into the life of one man over one week. His name is also Paterson, and he's a bus driver played by Adam Driver, which is a nimble bit of doubling that was almost certainly a coincidence, but ties in nicely with everything else that the movie is doing.

For as it turns out, Jarmusch's Paterson is a descendant of Williams's Paterson in more than just setting. As has been done a few times, but not recently that I can think of and not in such a thoroughgoing way, the film is structured according to the principles of poetry, not narrative. Which is to say, it's long on imagery and longer on what we might call rhetorical devices, including repetition and parallelism - the basic unit of Paterson-the-movie is the single day, always beginning with the same shot of Paterson-the-man and his girlfriend Laura (Golshifteh Farahani) lying in bed, and generally proceeding through the same order of events, though the specific details are always a touch different. The exact cadence of his conversations with his supervisor Donny (Rizwan Manji) shifts, he eavesdrops on a different conversation between passengers on his bus, he encounters different sets of twins, or doppelgängers, or whatever we want to make of the film's extensive population of individuals who precisely resemble each other. Perhaps we're not even supposed to assume that these people and conversations and encounters all literally exist, but that they're simply extensions of Paterson's brain, visual representations of how he thinks about the world. Because he's also a poet, our Paterson, and Paterson is mostly a film about how he thinks about the things he encounters before transforming them into writing.

It would be extremely easy for the film to belabor this, as a Marty-style "the working class has a soul, man" affair. Thank God Almighty that it doesn't. In fact, Jarmusch barely registers that this could be regarded as any kind of surprise at all; it's simply who Paterson is. Driver plays the role with an extremely satisfying lack of fuss or gilded soulfulness, which proves to be a godsend for the movie; with no special pleading that we should regard Paterson as any kind of prophet or philosopher, the film doesn't get tangled up in grandiose statements about what art is or does, how it's made, how it's consumed. Instead, we're invited to regard poetry as an act, rather than a belief system - a miraculously unromantic notion that treats poem-writing with far more dignity than all the movies that have, swooning, sketched it out as a thunderbolt of inspiration. We see Paterson tinker and labor, attempting to reformat his emotional experiences into words, as an act of communication and of self-analysis. Driver's thoughtful, slightly perturbed facial expressions are perfectly attenuated to increase this sense, allowing him the yearning soul of a poet without losing sight of the concrete facts of the town of Paterson, the house and the bed and the amazingly expressive, contemplative bulldog Marvin (posthumous Palme Dog winner Nellie) who lives with Paterson and Laura, and is by any reasonable yardstick the film's third most interesting and well-realised character.

Paterson is, in short, a feature-length exploration of the linkages between routine, unexceptional daily life and the creation of art, and the kind of personality it takes to transform one into the other. It does this incredibly well, not just through its regimented structure but also its equally repetitive and formulaic visuals, which have adopted the status of punctuation marks - never periods, but always semicolons and commas and the like - by the time the film ends. The few dramatically unexceptional events depicted in the film are, in this scheme, like the unexpected bursts of imagery that give a poem its emotional force - the sensual "they were delicions / so sweet / and cold" that forcefully pays off the quotidian "I have eaten / the plums / that were in / the icebox", to use the example of the one William Carlos Williams poem that shows up prominently in the film's script.

The extraordinarily persuasive everyday-ness is so strong, in fact, that it's a crushing disappointment when Jarmusch abandons it on the last two days of his week; without giving away what happens, Paterson very swiftly becomes exactly the story you would predict, with exactly the clichéd crisis that you'd expect this movie was leading up to if it was some hokey, sentimental bullshit about the striving power of the poet's heart in the face of setbacks. I'm not going to go all the way around to "the ending ruins Paterson", especially because the ending is quite good, with a Japanese tourist (Nagase Masatoshi) on hand to return this to the realm of Jarmusch's more characteristically wry absurdism (among other things, the character is an apparent nod back to the director's Mystery Train). It is the climax that almost ruins Paterson, turning it into something trite and obvious and overdone, and along with the handful of dangling concepts and inexplicable moments, it's enough to make a by-all-means very great film feel like it got something small but critical wrong.