Universal Horror: Post no gills

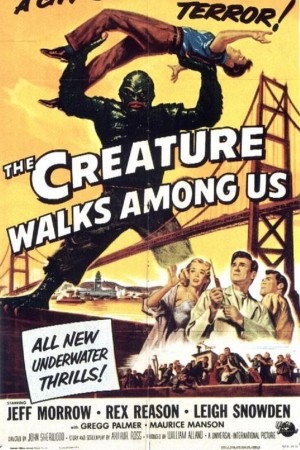

Like many another film lucky enough to share a series with a real piece of crap, the 1956 sci-fi/horror film The Creature Walks Among Us had a nice, easy, eminently surmountable bar to clear. That being, in this case, to be better than 1955's Revenge of the Creature, an endlessly tedious film about which I have absolutely nothing nice to say beyond to note its value as an historic document. The Creature Walks Among Us (to date, the third and last film officially starring Universal's Gill Man, though they've been trying to get a remake off the ground for well more than a decade) at least manages to hit that target, no matter what sins it commits in its own right. It's slow moving in places one really wishes it weren't, but nothing it does is as thoroughly enervating as the previous film's ages-long sequences set in Marineland aquariums. If nothing else, it's different enough to be admirably batshit crazy.

For the second movie running, a group of people refuse to believe the evidence of the last movie, in which the Gill Man from the Amazon jungle (Ricou Browning returns once again for the underwater scenes; this time, Don Megowan fills the suit on land) was shot quite dead before sinking to the bottom of a body of water. This time, the Gill Man hunt consists of four scientists: Dr. Thomas Morgan (Rex Reason, an excellent name for an actor playing a scientist in a '50s movie), Dr. Borg (Maurice Manson), Dr. Johnson (James Rawley), and leading the whole team, the brittle Dr. William Barton (Jeff Morrow). There are two other people along for the trip: their guide from the coast of Florida into the Everglades, Jed Grant (Gregg Palmer), and Dr. Barton's considerably younger wife Marcia (Leigh Snowden). We learn a couple of things early on, one of which is that Marcia is a terrible person: practically the first action she performs is to cheerfully start taking potshots at sharks with with a rifle, cheerily announcing that she killed two for no good goddamn reason other than she was bored and the gun was like, right there; later, she'll endanger the entire mission through her petulant insistence on going swimming and diving so deep that she starts to hallucinate. The other thing is that we still like Marcia much, much, much, much, much more than her husband, who lacks even the slightest vestigial trace of a positive character trait: he's peremptory and cruel in his applications of science, and an utter monster of paranoid jealousy and overt, intense emotional abuse towards his wife. He's such a rotter of a chauvinist pig that even the other '50s movie male scientists are made acutely uncomfortable by it.

So these will be the people we spend most of the film's 78 minutes with, and we thereby come to the first point of utterly strange behavior that The Creature Walks Among Us is up to: this is a marital drama, straight-up. It is, first and foremost, about the wretched meanness of Barton, who possesses his trophy wife with more vicious hatred than anything that resembles even a bent version of love, and how Marcia tries to deal with it by finding some solace in her flirtations with Jed (who's no real prize himself, for that matter, but making love to Herman Göring would seem like a trade-up after years of marriage to William Barton), thereby making him even angrier, and even more chilly and punishing in his attitudes. This is the story: the happenings of the Gill Man, and how he comes to walk among us, are there more to flesh out the story of the toxic Barton marriage than to serve as the main narrative thrust in their own right.

So that's... an approach. I have to credit Arthur Ross for refusing to simply replicate the beats of the script he co-wrote for the first Creature from the Black Lagoon. The question of whether the thing he provided is actually preferable to that perhaps remains open. The Creature Walks Among Us is not a terribly fast-moving thing, and it is unambiguously draining to spend time around such an unpleasant experience, particularly given that nobody walks into a movie like this because they were psychologically prepped for an ascetic domestic drama. It would be no different than if the entire fourth episode of Scenes from a Marriage depicted, in real time, Erland Josephson's desperate attempt to fight off an army of were-lizards. There's subverting audience expectations, and then there's missing the goddamn point.

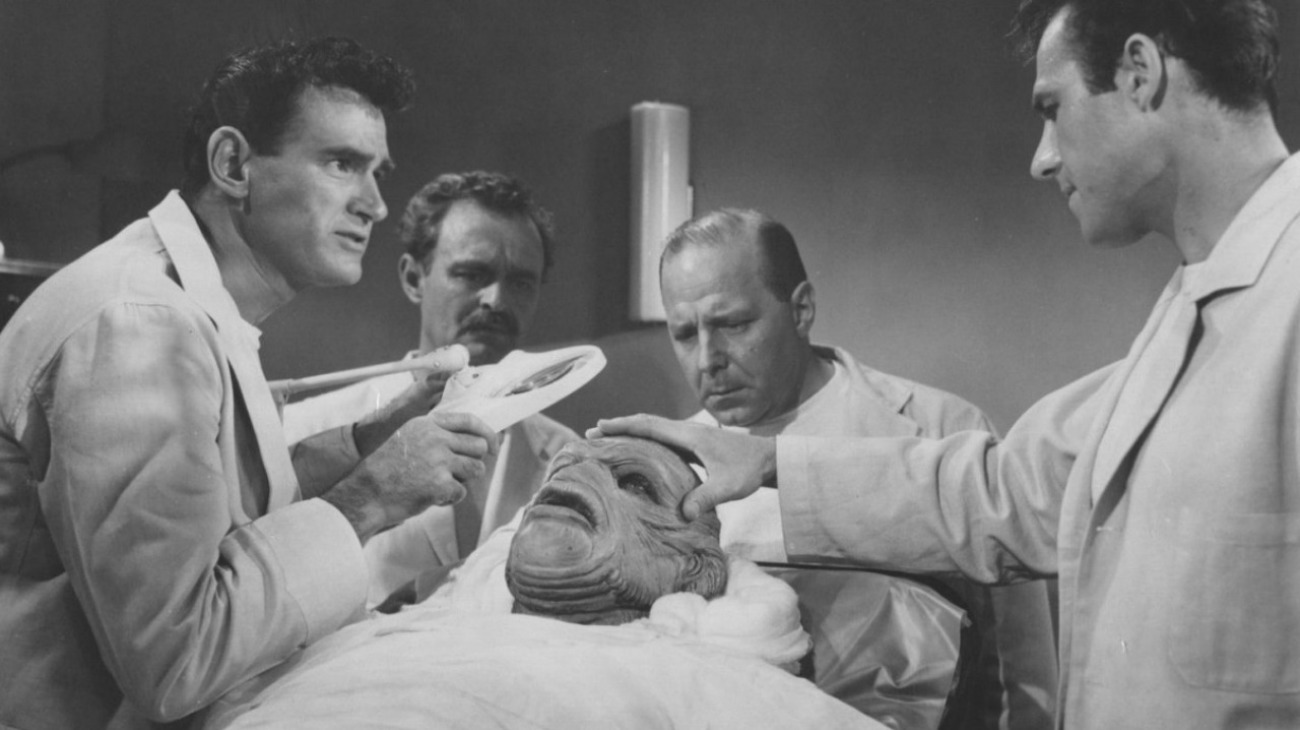

Still, Ross succeeds in writing characters who feel plausibly, recognisably human in ways that Martin Berkeley's script for Revenge of the Creature doesn't even attempt. We sure as hell are grading on a curve here, but that is sometimes the only way to keep one's soul intact. So anyway, the team captures the Gill Man, but in the process accidentally set him on fire. The scientists are amazed to discover that as his scaly surface burns away, he's left with much softer, almost human-like skin; the even more amazing discovery is that he has something approximately analogous to human lungs, and can in principle breathe air; the most amazing of all is that, in the span of hours, their attempt to save him by giving him a tracheotomy somehow accelerates the growth of his lungs, effectively turning him into an air-breathing land animal, not a water-breathing fish-man. This is also an approach, and the kind that you stumble upon, I think, when you secretly detest the series you're working on and simply want to ruin it so badly that nobody will ever be able to restore it.

That being said, the smoother, more humanGill Lung Man suit designed for this film is acutely creepy and offers Megowan vastly more room to emote and put across something of the creature's turmoil than any of his predecessors. This is a very obviously feeling Gill Man, one that we generally feel a lot sorrier for than any of the disposable, interchangeable, unlikable humans responsible for his plight; but he is also a Gill Man who looks even more like some kind of impossibility vomited out by nature during one of her nastier moods, getting us closer to proper, lasting horror than anything the series has done. Notwithstanding the trashy goofiness of the premise, which could only ever have been concocted in the feverish world of the '50s drive-in movie, The Creature Walks Among Us offers enough genuinely arresting visuals that it remains memorable and effective almost despite itself. One longs to know what the same monster in a more stable, appropriate, effective storyline might have yielded.

I have much the same feeling about the film's obvious best scene, a nighttime hunt through the Everglades, slowly plowing through the river to find the Gill Man. The film's director, John Sherwood, was almost exclusively an assistant director, but throughout the film, he manages to show how much he learned from a collection of great and mediocre artists; the film generally looks good, regardless of what else is falling down. Even so, the nighttime sequence is a cut above: shot by cinematographer Maury Gertsman in some of the most dauntingly pitch black night-for-night sequences you could ever hope to see, the screen often filling up with nothing but darkness, a few spots of lighter objects on the surface of the water, and occasional reflected light on the water itself. It is wonderfully atmospheric, the one place where Sherwood achieves the same kind of "let us permit the camera to linger and observe" strategy that Jack Arnold employed in Creature from the Black Lagoon to make the river and lagoon such vivid locations (of course, it's the strategy that Arnold then used in Revenge of the Creature to make Marineland seem like an unending purgatory). It's a great sequence that earnestly deserves a better movie, but at least it's something. I would certainly not want to imagine the grinding story of Barton's constant abuse of his wife without this unexpectedly stylish genre film treating hiding right there in the middle of it.

Reviews in this series

Creature from the Black Lagoon (Arnold, 1954)

Revenge of the Creature (Arnold, 1955)

The Creature Walks Among Us (Sherwood, 1956)

For the second movie running, a group of people refuse to believe the evidence of the last movie, in which the Gill Man from the Amazon jungle (Ricou Browning returns once again for the underwater scenes; this time, Don Megowan fills the suit on land) was shot quite dead before sinking to the bottom of a body of water. This time, the Gill Man hunt consists of four scientists: Dr. Thomas Morgan (Rex Reason, an excellent name for an actor playing a scientist in a '50s movie), Dr. Borg (Maurice Manson), Dr. Johnson (James Rawley), and leading the whole team, the brittle Dr. William Barton (Jeff Morrow). There are two other people along for the trip: their guide from the coast of Florida into the Everglades, Jed Grant (Gregg Palmer), and Dr. Barton's considerably younger wife Marcia (Leigh Snowden). We learn a couple of things early on, one of which is that Marcia is a terrible person: practically the first action she performs is to cheerfully start taking potshots at sharks with with a rifle, cheerily announcing that she killed two for no good goddamn reason other than she was bored and the gun was like, right there; later, she'll endanger the entire mission through her petulant insistence on going swimming and diving so deep that she starts to hallucinate. The other thing is that we still like Marcia much, much, much, much, much more than her husband, who lacks even the slightest vestigial trace of a positive character trait: he's peremptory and cruel in his applications of science, and an utter monster of paranoid jealousy and overt, intense emotional abuse towards his wife. He's such a rotter of a chauvinist pig that even the other '50s movie male scientists are made acutely uncomfortable by it.

So these will be the people we spend most of the film's 78 minutes with, and we thereby come to the first point of utterly strange behavior that The Creature Walks Among Us is up to: this is a marital drama, straight-up. It is, first and foremost, about the wretched meanness of Barton, who possesses his trophy wife with more vicious hatred than anything that resembles even a bent version of love, and how Marcia tries to deal with it by finding some solace in her flirtations with Jed (who's no real prize himself, for that matter, but making love to Herman Göring would seem like a trade-up after years of marriage to William Barton), thereby making him even angrier, and even more chilly and punishing in his attitudes. This is the story: the happenings of the Gill Man, and how he comes to walk among us, are there more to flesh out the story of the toxic Barton marriage than to serve as the main narrative thrust in their own right.

So that's... an approach. I have to credit Arthur Ross for refusing to simply replicate the beats of the script he co-wrote for the first Creature from the Black Lagoon. The question of whether the thing he provided is actually preferable to that perhaps remains open. The Creature Walks Among Us is not a terribly fast-moving thing, and it is unambiguously draining to spend time around such an unpleasant experience, particularly given that nobody walks into a movie like this because they were psychologically prepped for an ascetic domestic drama. It would be no different than if the entire fourth episode of Scenes from a Marriage depicted, in real time, Erland Josephson's desperate attempt to fight off an army of were-lizards. There's subverting audience expectations, and then there's missing the goddamn point.

Still, Ross succeeds in writing characters who feel plausibly, recognisably human in ways that Martin Berkeley's script for Revenge of the Creature doesn't even attempt. We sure as hell are grading on a curve here, but that is sometimes the only way to keep one's soul intact. So anyway, the team captures the Gill Man, but in the process accidentally set him on fire. The scientists are amazed to discover that as his scaly surface burns away, he's left with much softer, almost human-like skin; the even more amazing discovery is that he has something approximately analogous to human lungs, and can in principle breathe air; the most amazing of all is that, in the span of hours, their attempt to save him by giving him a tracheotomy somehow accelerates the growth of his lungs, effectively turning him into an air-breathing land animal, not a water-breathing fish-man. This is also an approach, and the kind that you stumble upon, I think, when you secretly detest the series you're working on and simply want to ruin it so badly that nobody will ever be able to restore it.

That being said, the smoother, more human

I have much the same feeling about the film's obvious best scene, a nighttime hunt through the Everglades, slowly plowing through the river to find the Gill Man. The film's director, John Sherwood, was almost exclusively an assistant director, but throughout the film, he manages to show how much he learned from a collection of great and mediocre artists; the film generally looks good, regardless of what else is falling down. Even so, the nighttime sequence is a cut above: shot by cinematographer Maury Gertsman in some of the most dauntingly pitch black night-for-night sequences you could ever hope to see, the screen often filling up with nothing but darkness, a few spots of lighter objects on the surface of the water, and occasional reflected light on the water itself. It is wonderfully atmospheric, the one place where Sherwood achieves the same kind of "let us permit the camera to linger and observe" strategy that Jack Arnold employed in Creature from the Black Lagoon to make the river and lagoon such vivid locations (of course, it's the strategy that Arnold then used in Revenge of the Creature to make Marineland seem like an unending purgatory). It's a great sequence that earnestly deserves a better movie, but at least it's something. I would certainly not want to imagine the grinding story of Barton's constant abuse of his wife without this unexpectedly stylish genre film treating hiding right there in the middle of it.

Reviews in this series

Creature from the Black Lagoon (Arnold, 1954)

Revenge of the Creature (Arnold, 1955)

The Creature Walks Among Us (Sherwood, 1956)