Sexual behavior in the human male

A review requested by Robert J, with thanks for contributing to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

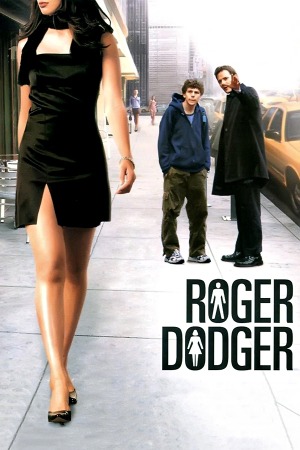

A person with the slightest knowledge of contemporary American film style and genre could accurately date Roger Dodger to the first three years of the 2000s based solely on onscreen evidence, and I'm not even counting the ethereally youthful face of Baby Jesse Eisenberg, 18 years old at the release of this, his first feature. The film is a very particular kind of indie that came out in a relatively narrow window of time; it's a dialogue-driven character study focused on sexual psychology that has the approximate rhythms of a comedy but is filled with so much acid that it's hard to say, in good faith, that it's "funny". It also wears its low-scale production with considerable pride, wielding such a small number of locations and characters that at times it feels more like a theatrical piece that wandered into the movies almost in defiance of the traditional expectations of what the proper dimensions of cinema should be. It is exactly right that it came out in 2002, the same year as Secretary and Igby Goes Down: something about that trifecta (and Roger Dodger and Igby Goes Down, in particular, are impossible for me to mentally segregate for some reason), which all received their commercial release in the United States during a seven-week span that autumn, feels like the last gasp of a certain breed of talky character study which used to dominate the conversation around "independent cinema" at a time when "independent cinema" was something large numbers of people still talked about.

Roger Dodger happens to hearken back to one of the earlier hits in that same breed of indie, Neil LaBute's black-hearted In the Company of Men from 1997 (which actually was a stage play first, and I don't have wonder if that model is part of what gives Roger Dodger its theatrical texture). They are both stories about two men bonding, after a fashion, designed primarily to showcase the awful depths of meanness and savagery that can be reached by arrogant masculinity. Our alpha male for the evening is one Roger Swanson (Campbell Scott), who never gets any particularly more appealing than we we meet him at a chic New York business lunch with three co-workers - including his boss, Joyce (Isabella Rossellini) - as he regales them with his dubious sociological theories about the battle of the sexes (capsule version: men are useless mounds of flesh, women are vaguely evil), expressed in terms so purposefully crude that we get the impression, not that Roger is a boor, but that he wants to see how uncomfortable he can make the people around him, just as a lark. This is, indeed, the only social strategy he seems to know. After he's dumped by his current fuck buddy - who is also Joyce, as it so happens, and somehow, Roger seems so reptilian by this point that it feels like the ethical lapse is worse on his side - he immediately plunges himself into the singles bars, where his primary method of attracting women is to express complex, hugely insulting and aggressive readings of their psychological state, and assuring them that he'll be happy to let them vent their rage against an absent father figure by having sex with them. Implicitly, this works sometimes, though we never see that happen.

Right about here is where Roger's 16-year-old nephew Nick (Eisenberg), the son of his estranged sister, shows up. In town for a college visit, the virginal nerd shows up unannounced to ask for a place to sleep, and to get some advice from his uncle on how to stop being such a nerd, or at least such a virgin, and this is advice that Roger is eager to impart. Over the course of the movie, he imparts lesson after lesson onto Nick, all of those lessons based in the most nihilistic and toxic understanding of how people function. It's not even good advice; Roger's approach to courtship is apparently to bully women into wanting to have sex, and striking until he lucks his way into finding someone who doesn't immediately recoil from him. It's hard to say exactly what's motivating him: a desire to sexually humiliate the young boy out of boredom, the hope of weaponising another man in the fight against the female sex, or maybe (and most horribly of all) the belief that this is actually how the world works. The film does offer one very leading glimpse into Roger's philosophy: the man, an advertising copywriter, describes his job as making people feel miserable enough about themselves to buy what he wants to sell, and you'd have to be paying no attention at all to miss that this is an exact description of his approach to sex. An approach that he watches fail in real time as the bumbling, nervous Nick manages to outdo him in impressing a pair of 30something women, Andrea (Elizabeth Berkley) and Sophie (Jennifer Beals), simply by being honest and talking to them like they have inner lives that he's interested in learning more about.

The great, unanswerable sin of Roger Dodger is the same as so, so many script-heavy indie films for generations: it's never really very interesting to look at. I keep talking about it as theatrical, which can mean a few different things, but the one I mean is that it would be fundamentally the same experience if you saw these same four actors reciting their dialogue in an empty black box theater. Writer-director Dylan Kidd (a first-timer whose career petered out after his 2004 follow-up p.s.) is by no means without talent, but his interest is clearly much more in the performances and words, and I suppose that's fine. The words, after all, are generally quite good; sometimes prone to stating overtly what would be better-suited to implication (such as the "I make people hate themselves for money" speech), but generally an impressive contribution to that body of films in which over-literate New Yorkers vomit a barrage of finely-shaped syllables in the belief that sophistication and wit make up for having no inner self. Parts of it are a little over-written, the clear result of a screenwriter in love with language just a little bit more than he's in love with character logic, but it's nothing that the film can't survive.

Meanwhile, the performances are absolutely superb, and that's where the film wants to live. The quartet of Scott, Eisenberg, Berkley, and Beals, around him the great majority of the film revolves, are each perfect in their own way. The women have the trickier parts: it is very important to the way the film functions that we understand everything going on in Andrea and Sophie's heads without the script ever breaking away from its tight alignment to Roger's perspective, which falls entirely on the acting: questions of why the pair doesn't leap back from Roger and Nick immediately, why the women allow themselves to become fascinated by a teenage boy, and how much of Roger's bullying they can take before snapping are answered solely in things like facial expressions and posture, since the script is structurally incapable of answering them, by design.

Scott, however, makes the movie. Roger Dodger is a wallow in the depths of toxic masculinity; that is its primary reason for being. "Here is a very awful man," the film states, "and here is what it looks like when you life a lifestyle wherein you shall never be seriously be called to account for being so awful". There's a stab at showing he's in some way dimly aware that his life is a fetid swamp of self-serving behavior, in the last few scenes where he stops trying to ruin Nick, but I'm not entirely sure I buy them; Kidd has too convincingly shown how perfect Roger has become at not confronting the ramifications of his actions for one long night of the soul to turn him. Anyway, my point is that this could be simply miserable and vile, and it's not, and that is almost entirely on Scott's performance. For the film to be watchable, not to mention for it to be believable that any woman would ever have sex with Roger, he needs to be in some way charismatic, and Scott provides this. For it to be true to its themes, we must also never, ever like him, and Scott provides this also.

It's a tremendous piece of empathetic acting that makes it very clear exactly what Roger believes and how his actions follow along in crisp, stately logic from that point, but which never finds the actor requesting our sympathy or love. Scott is not afraid to make Roger ice cold and utterly cruel, even as he delights in juggling Kidd's dialogue and beam at the women he flirts with throughout the film with the unthreatening handsomeness of a living Ken doll. In one key scene where he's been embarrassed by Nick and responds by embarrassing the boy right back, Scott delves into something nastier still than mere coldness: there's a raging tantrum caught in the back of his throat as he snarls out lines. The performance is a perfect balance of "let us understand, intimately, why Roger behaves this way" and "let us righteously condemn him for his behavior", and that balance is the central motivating force of the entire film. If we don't find him in some way charming, the film would be too bitter for words; as it is, he's to reason that Roger Dodger is, when all is said and done, a bright and snappy comedy, or at least "comedy", and the source of most of the appeal of a film that bets everything on its human characters.

A person with the slightest knowledge of contemporary American film style and genre could accurately date Roger Dodger to the first three years of the 2000s based solely on onscreen evidence, and I'm not even counting the ethereally youthful face of Baby Jesse Eisenberg, 18 years old at the release of this, his first feature. The film is a very particular kind of indie that came out in a relatively narrow window of time; it's a dialogue-driven character study focused on sexual psychology that has the approximate rhythms of a comedy but is filled with so much acid that it's hard to say, in good faith, that it's "funny". It also wears its low-scale production with considerable pride, wielding such a small number of locations and characters that at times it feels more like a theatrical piece that wandered into the movies almost in defiance of the traditional expectations of what the proper dimensions of cinema should be. It is exactly right that it came out in 2002, the same year as Secretary and Igby Goes Down: something about that trifecta (and Roger Dodger and Igby Goes Down, in particular, are impossible for me to mentally segregate for some reason), which all received their commercial release in the United States during a seven-week span that autumn, feels like the last gasp of a certain breed of talky character study which used to dominate the conversation around "independent cinema" at a time when "independent cinema" was something large numbers of people still talked about.

Roger Dodger happens to hearken back to one of the earlier hits in that same breed of indie, Neil LaBute's black-hearted In the Company of Men from 1997 (which actually was a stage play first, and I don't have wonder if that model is part of what gives Roger Dodger its theatrical texture). They are both stories about two men bonding, after a fashion, designed primarily to showcase the awful depths of meanness and savagery that can be reached by arrogant masculinity. Our alpha male for the evening is one Roger Swanson (Campbell Scott), who never gets any particularly more appealing than we we meet him at a chic New York business lunch with three co-workers - including his boss, Joyce (Isabella Rossellini) - as he regales them with his dubious sociological theories about the battle of the sexes (capsule version: men are useless mounds of flesh, women are vaguely evil), expressed in terms so purposefully crude that we get the impression, not that Roger is a boor, but that he wants to see how uncomfortable he can make the people around him, just as a lark. This is, indeed, the only social strategy he seems to know. After he's dumped by his current fuck buddy - who is also Joyce, as it so happens, and somehow, Roger seems so reptilian by this point that it feels like the ethical lapse is worse on his side - he immediately plunges himself into the singles bars, where his primary method of attracting women is to express complex, hugely insulting and aggressive readings of their psychological state, and assuring them that he'll be happy to let them vent their rage against an absent father figure by having sex with them. Implicitly, this works sometimes, though we never see that happen.

Right about here is where Roger's 16-year-old nephew Nick (Eisenberg), the son of his estranged sister, shows up. In town for a college visit, the virginal nerd shows up unannounced to ask for a place to sleep, and to get some advice from his uncle on how to stop being such a nerd, or at least such a virgin, and this is advice that Roger is eager to impart. Over the course of the movie, he imparts lesson after lesson onto Nick, all of those lessons based in the most nihilistic and toxic understanding of how people function. It's not even good advice; Roger's approach to courtship is apparently to bully women into wanting to have sex, and striking until he lucks his way into finding someone who doesn't immediately recoil from him. It's hard to say exactly what's motivating him: a desire to sexually humiliate the young boy out of boredom, the hope of weaponising another man in the fight against the female sex, or maybe (and most horribly of all) the belief that this is actually how the world works. The film does offer one very leading glimpse into Roger's philosophy: the man, an advertising copywriter, describes his job as making people feel miserable enough about themselves to buy what he wants to sell, and you'd have to be paying no attention at all to miss that this is an exact description of his approach to sex. An approach that he watches fail in real time as the bumbling, nervous Nick manages to outdo him in impressing a pair of 30something women, Andrea (Elizabeth Berkley) and Sophie (Jennifer Beals), simply by being honest and talking to them like they have inner lives that he's interested in learning more about.

The great, unanswerable sin of Roger Dodger is the same as so, so many script-heavy indie films for generations: it's never really very interesting to look at. I keep talking about it as theatrical, which can mean a few different things, but the one I mean is that it would be fundamentally the same experience if you saw these same four actors reciting their dialogue in an empty black box theater. Writer-director Dylan Kidd (a first-timer whose career petered out after his 2004 follow-up p.s.) is by no means without talent, but his interest is clearly much more in the performances and words, and I suppose that's fine. The words, after all, are generally quite good; sometimes prone to stating overtly what would be better-suited to implication (such as the "I make people hate themselves for money" speech), but generally an impressive contribution to that body of films in which over-literate New Yorkers vomit a barrage of finely-shaped syllables in the belief that sophistication and wit make up for having no inner self. Parts of it are a little over-written, the clear result of a screenwriter in love with language just a little bit more than he's in love with character logic, but it's nothing that the film can't survive.

Meanwhile, the performances are absolutely superb, and that's where the film wants to live. The quartet of Scott, Eisenberg, Berkley, and Beals, around him the great majority of the film revolves, are each perfect in their own way. The women have the trickier parts: it is very important to the way the film functions that we understand everything going on in Andrea and Sophie's heads without the script ever breaking away from its tight alignment to Roger's perspective, which falls entirely on the acting: questions of why the pair doesn't leap back from Roger and Nick immediately, why the women allow themselves to become fascinated by a teenage boy, and how much of Roger's bullying they can take before snapping are answered solely in things like facial expressions and posture, since the script is structurally incapable of answering them, by design.

Scott, however, makes the movie. Roger Dodger is a wallow in the depths of toxic masculinity; that is its primary reason for being. "Here is a very awful man," the film states, "and here is what it looks like when you life a lifestyle wherein you shall never be seriously be called to account for being so awful". There's a stab at showing he's in some way dimly aware that his life is a fetid swamp of self-serving behavior, in the last few scenes where he stops trying to ruin Nick, but I'm not entirely sure I buy them; Kidd has too convincingly shown how perfect Roger has become at not confronting the ramifications of his actions for one long night of the soul to turn him. Anyway, my point is that this could be simply miserable and vile, and it's not, and that is almost entirely on Scott's performance. For the film to be watchable, not to mention for it to be believable that any woman would ever have sex with Roger, he needs to be in some way charismatic, and Scott provides this. For it to be true to its themes, we must also never, ever like him, and Scott provides this also.

It's a tremendous piece of empathetic acting that makes it very clear exactly what Roger believes and how his actions follow along in crisp, stately logic from that point, but which never finds the actor requesting our sympathy or love. Scott is not afraid to make Roger ice cold and utterly cruel, even as he delights in juggling Kidd's dialogue and beam at the women he flirts with throughout the film with the unthreatening handsomeness of a living Ken doll. In one key scene where he's been embarrassed by Nick and responds by embarrassing the boy right back, Scott delves into something nastier still than mere coldness: there's a raging tantrum caught in the back of his throat as he snarls out lines. The performance is a perfect balance of "let us understand, intimately, why Roger behaves this way" and "let us righteously condemn him for his behavior", and that balance is the central motivating force of the entire film. If we don't find him in some way charming, the film would be too bitter for words; as it is, he's to reason that Roger Dodger is, when all is said and done, a bright and snappy comedy, or at least "comedy", and the source of most of the appeal of a film that bets everything on its human characters.