Loved and lost

Whatever else we can say about it, L'attesa is hella art film. If you fell asleep in 1965 and just woke up, you'd probably find nothing exceptional about it, assuming that all European (and especially Italian) "serious cinema" was like this: gorgeously shot, minimally paced, perhaps more ambiguous than it needs to be, chilly and arch in its depiction of human behavior to the point that the characters feel like abstractions than psychological beings. I mean every last one of those things as a compliment, but I won't hold it against you if it sounds instead like I've described something icy and airless. It is both of those.

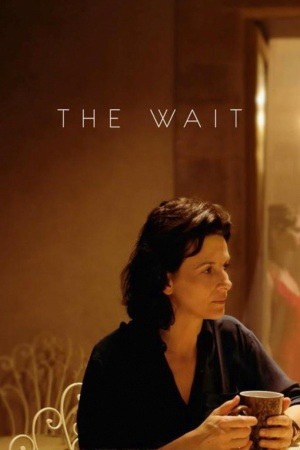

The scenario is one of those things that exists solely to give actors a chance to work through a gamut of challenges (and indeed, the script by director Piero Messina and his colleagues is derived from playwright Luigi Pirandello, who made "throw random and/or arbitrary challenges at actors" into an entire career): Giuseppe is dead. The film never entirely confirms this, but Messina leaves precious little doubt in the way that various side characters look sandblasted with guilt and grief anytime his name is mentioned (frankly, not only does it seem pretty clear that Giuseppe is dead, it seems pretty clear that he killed himself). But what we definitely know for sure is that Giuseppe is someplace not here, and the house where he used to be is closed up for mourning, with nobody mourning harder than Anna (Juliette Binoche), Giuseppe's mother. And who do you suppose should arrive at this sad place than Jeanne (Lou de Laâge, a teen star managing the shift to art films well, though she's much too callow to pull focus from her co-star)), the fiancée that Giuseppe never told his mother about.

Clarifying that her brother has passed away, and that Giuseppe will be showing up in a few days - Easter Sunday, of all metaphorically freighted possibilities - Anna invites Jeanne to stay and wait (The Wait is the English translation of the film's title). This is theoretically an act of kindness to the young woman, but it is pretty clear to watch them interact that Anna is desperately hungry: for what, we have to rely mostly on implication and Binoche's superb performance, but some of it, surely, is a chance to learn more about her son and in some way resurrect him by imagining him as a man rather than a son. Some of it is the possibility of watching Jeanne glide through life as young people will, and snatch some vicarious pleasure through seeing Jeanne have all the fun that Anna can't, and maybe never did.

I don't want to race past it too fast: this is a grandmaster-level performance from Binoche. It's been a few years since we've seen her do something really, genuinely hard, and it's a glorious privilege to be reminded of what she's capable of when she sets her mind to it. Apparently design, Anna as a script construction is all notes and fragments, ideas about how the character should function that aren't necessarily given concrete life. We might honestly ask ourselves if this is for any other reason so that the film can be properly esoteric and artfully cryptic (which isn't nothing - there's something about the way that L'attesa demands attentive viewing that in turn rewards us for unpacking the film ourselves rather than have it chewed up and predigested for us) but it at least gives Binoche plenty of room to work with small gestures and expressions that build outward from the pencil sketch she's been provided with. The resulting character is an astonishment, seething, raw-nerve emotions that are all kept buried deep below the surface - not as an act of subterfuge, but due to the numbing effects of potent depression and grief. If it's possible for something to be expressionistically underplayed, Binoche achieves that here: the way she non-verbally depicts Anna's state of mind through weary poses and lifeless movements, or even just the limited set of expressions she fixes onto her face throughout, has the emphatic over-the-top presence of really fine silent movie acting from a more theatrical rather than realist tradition, and yet the limited dialogue and the hushed way Binoche delivers it suggests to our sound-trained eyes and ears that she's barely doing anything at all.

Anyway, Binoche leaves L'attesa as an extraordinarily wracking depiction of grief so intense and regenerating that it shades into derangement. In fairness, she is not alone. Messina cut his teeth training under Paolo Sorrentino, and like that director, he has a knack for depicting upper-class spaces as expressions of character psychology not as on a metaphorical or symbolic level, but tonally (this also means that the not-insignificant population of Sorrentino haters would be well-served by passing L'attesa by; it feels very much in the fashion of his work, only with a much darker emotional edge and extremely narrow geographic confinement). He and cinematographer Francesco Di Giacomo have set up quite the array of striking imagery, too, gorgeous compostions of soft, quiet, melancholy spaces, with the repetition of set-ups, locations, or even just structural shapes providing a rhythm and shape to the film that accentuates the tension between Anna and Jeanne as the latter grows more and more restless while the former becomes more desperate; so too does the relative lack of variety or flexibility in the midst of the non-stop parade of perfectly designed, graphically satisfying compositions serve to increase an aura of depressed hopelessness.

It's all very sophisticated in aesthetic conception and execution, I think, though fairly blunt in its emotional message: loss causes enormous pain. That's really all there is to it, and the rest of the movie is variations on what that pain is and how it manifests; in the lies Anna tells both to satisfy herself and to protect Jeanne; in the raw-skinned presence of every misery Binoche can conjure up and then not express except through innuendo and asides; in the general hushed, sepulchral air of the thing. Which is, in turn, its appeal: seeing a simple feeling expressed with great artistry and intensity. In which respect, it's every respect the Italian art movie, and I know too many people with a built-in resistance to such things to act like this is a slam-dunk masterpiece for the ages. But it knocked me for a loop, anyway.

The scenario is one of those things that exists solely to give actors a chance to work through a gamut of challenges (and indeed, the script by director Piero Messina and his colleagues is derived from playwright Luigi Pirandello, who made "throw random and/or arbitrary challenges at actors" into an entire career): Giuseppe is dead. The film never entirely confirms this, but Messina leaves precious little doubt in the way that various side characters look sandblasted with guilt and grief anytime his name is mentioned (frankly, not only does it seem pretty clear that Giuseppe is dead, it seems pretty clear that he killed himself). But what we definitely know for sure is that Giuseppe is someplace not here, and the house where he used to be is closed up for mourning, with nobody mourning harder than Anna (Juliette Binoche), Giuseppe's mother. And who do you suppose should arrive at this sad place than Jeanne (Lou de Laâge, a teen star managing the shift to art films well, though she's much too callow to pull focus from her co-star)), the fiancée that Giuseppe never told his mother about.

Clarifying that her brother has passed away, and that Giuseppe will be showing up in a few days - Easter Sunday, of all metaphorically freighted possibilities - Anna invites Jeanne to stay and wait (The Wait is the English translation of the film's title). This is theoretically an act of kindness to the young woman, but it is pretty clear to watch them interact that Anna is desperately hungry: for what, we have to rely mostly on implication and Binoche's superb performance, but some of it, surely, is a chance to learn more about her son and in some way resurrect him by imagining him as a man rather than a son. Some of it is the possibility of watching Jeanne glide through life as young people will, and snatch some vicarious pleasure through seeing Jeanne have all the fun that Anna can't, and maybe never did.

I don't want to race past it too fast: this is a grandmaster-level performance from Binoche. It's been a few years since we've seen her do something really, genuinely hard, and it's a glorious privilege to be reminded of what she's capable of when she sets her mind to it. Apparently design, Anna as a script construction is all notes and fragments, ideas about how the character should function that aren't necessarily given concrete life. We might honestly ask ourselves if this is for any other reason so that the film can be properly esoteric and artfully cryptic (which isn't nothing - there's something about the way that L'attesa demands attentive viewing that in turn rewards us for unpacking the film ourselves rather than have it chewed up and predigested for us) but it at least gives Binoche plenty of room to work with small gestures and expressions that build outward from the pencil sketch she's been provided with. The resulting character is an astonishment, seething, raw-nerve emotions that are all kept buried deep below the surface - not as an act of subterfuge, but due to the numbing effects of potent depression and grief. If it's possible for something to be expressionistically underplayed, Binoche achieves that here: the way she non-verbally depicts Anna's state of mind through weary poses and lifeless movements, or even just the limited set of expressions she fixes onto her face throughout, has the emphatic over-the-top presence of really fine silent movie acting from a more theatrical rather than realist tradition, and yet the limited dialogue and the hushed way Binoche delivers it suggests to our sound-trained eyes and ears that she's barely doing anything at all.

Anyway, Binoche leaves L'attesa as an extraordinarily wracking depiction of grief so intense and regenerating that it shades into derangement. In fairness, she is not alone. Messina cut his teeth training under Paolo Sorrentino, and like that director, he has a knack for depicting upper-class spaces as expressions of character psychology not as on a metaphorical or symbolic level, but tonally (this also means that the not-insignificant population of Sorrentino haters would be well-served by passing L'attesa by; it feels very much in the fashion of his work, only with a much darker emotional edge and extremely narrow geographic confinement). He and cinematographer Francesco Di Giacomo have set up quite the array of striking imagery, too, gorgeous compostions of soft, quiet, melancholy spaces, with the repetition of set-ups, locations, or even just structural shapes providing a rhythm and shape to the film that accentuates the tension between Anna and Jeanne as the latter grows more and more restless while the former becomes more desperate; so too does the relative lack of variety or flexibility in the midst of the non-stop parade of perfectly designed, graphically satisfying compositions serve to increase an aura of depressed hopelessness.

It's all very sophisticated in aesthetic conception and execution, I think, though fairly blunt in its emotional message: loss causes enormous pain. That's really all there is to it, and the rest of the movie is variations on what that pain is and how it manifests; in the lies Anna tells both to satisfy herself and to protect Jeanne; in the raw-skinned presence of every misery Binoche can conjure up and then not express except through innuendo and asides; in the general hushed, sepulchral air of the thing. Which is, in turn, its appeal: seeing a simple feeling expressed with great artistry and intensity. In which respect, it's every respect the Italian art movie, and I know too many people with a built-in resistance to such things to act like this is a slam-dunk masterpiece for the ages. But it knocked me for a loop, anyway.