Whatever I feel like I wanna do, gosh!

A review requested by Carter Smith, with thanks for contributing to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

There's going to be a lot of wholly subjective, first-person claims in this review, I am sorry to say. But comedy is notoriously subjective and this is a specifically notoriously subjective comedy we have in front of us, and it is important that I lay out all my biases at the front, because the critic who feigns objectivity where he has none is an irresponsible & wicked critic. Anyway, the thing is that Napoleon Dynamite never had a chance with me from the start. Back in the summer of 2004, you may perhaps recall, there was an extraordinary fetish for the movie among the kind of high school and college students of a sufficiently adventurous bent that they'd track down indie movies in the first place, even non-threatening and wholly mainstream indies like this one. It was the quotable movie for the under-25 set, which meant that, years before I finally forced myself to sit through, it felt like I'd already seen the whole thing; and there is no hope for a comedy wherein you've already heard and not laughed at most of the jokes. It is impossible, in that kind of hyped-up environment, to experience the sense of delightfully astonished discovery that makes films like Napoleon Dynamite into word-of-mouth hits in the first place.

That being said, I looked forward, in an intellectually curious way, to seeing the film again with a decade and change of buffering from the thickest part of its faddish acclaim, to maybe have a chance to respond to it from a place of anything that wasn't ice-cold hostility. And in the end, while I still do not like Napoleon Dynamite, and I do not find it in any way funny, I certainly dislike it less. And there's stuff going on inside of it that I had previously failed to credit, though I won't swear that it's good stuff.

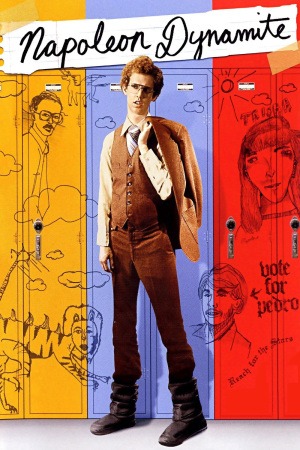

The film, written by husband-and-wife team Jerusha and Jared Hess - Jared also directed - is an almost entirely plotless amble around Preston, Idaho, the filmmakers' hometown. Our entry point and protagonist into this world is 16-year-old Napoleon Dynamite (Jon Heder), an exemplar of all those things we think about when the word "nerd" is spoken: tacky clothes, tunnel vision about his private obsessions, a near-complete lack of interest in communicating with other people in a normal way. His world is full of eccentrics no less insular than he, though for the most part they lack his frustrated hostility towards the world: some of the most important figures include his much older brother Kip (Aaron Ruell), who lives with him and their grandmother (Sandy Martin); Deb (Tina Marjorino), a shy entrepreneur who works odd jobs to raise money for college; Pedro (Efren Ramirez), a transfer student with an eerily unflappable mien, who becomes Napoleon's best and only real friend, and vice versa; and Rico (Jon Gries), Napoleon and Kip's uncle, who comes to watch the house while their grandma recovers from a dune buggy accident. Things don't really happen in any of their lives until almost the very end; mostly, it's just snippets of people trying to pass the time in a flyspeck like Preston, a place they've all lived so long that they don't even have the context to explain why they find it boring.

There are a lot of ways you could take this kind of anti-directional, slice-of-life storytelling; the one that Napoleon Dynamite picks is absurdist comedy, which I frankly don't think works very well. With its highly stylised performances of characters defined through their idiosyncratic interests, it's self-consciously "punchy" editing, and its squared-off compositions, Napoleon Dynamite resembles nothing so much as a Wes Anderson film, like so very many other indie movies of the early-to-mid 2000s. Except that Jared Hess and cinematographer Munn Powell, working from an ultra-relaxed, observational perspective shoot the film with a great deal of scratchy, dusty realism - the compositions might be completely indebted to Anderson, but the textures are from a wholly different mode of indie filmmaking altogether, one steeped in the documentary impulse and anxious to capture places with as much authenticity and detail as can be.

It's a unique combination, I have to give it that; I can't pretend, though, that it feels me with very much pleasure to watch it. The naturalism in the cinematography ties in with an overall laid-back approach, in which moments are paced out slowly, the actors themselves move slowly; it has the sleepy humid sensibility of, to name the first contemporaneous director who jumps to mind, David Gordon Green (though without Green's Malickian awe for the cinematic image). A hybrid Green and Anderson, two of the most celebrated indie auteurs of the early '00s, was surely going to happen, but it just as surely was going to turn into the odd duck that we have here. For me, it's a specific combination of absurd attitude and languid rhythm that absolutely murders the comedy. I can't tell the people who laugh at Napoleon Dynamite that they're wrong; funny can only be a matter of taste. But in this particular instance, I'm not even sure what's meant to be funny, I don't even see the shape of the humor: it seems like a bunch of strange, half-alien people talking in stilted ways, with Heder often launching into a braying howl of impatience with the morons around him that feels to me much too angry to ever laugh with it, or at it.

All of that being true, I have to admit that in one key respect, I had the film pegged wrong at first. Watching Napoleon Dynamite the first time felt like an exercise in complete rancidity: the Hesses seemed to hold every last one of their characters in deep contempt, looking on them as dimwitted rubes, and using Napoleon's curt sense of superiority half of the time as a tool for cutting down the rest of their cast, half of the time as a way of mocking Napoleon himself, who frequently seemed to be the butt of jokes that were nothing so much as mocking potshots at an autistic kid. I'm still not quite sure that I'm off-base with that last part: the film's concept of "socially awkward nerd" comes uncomfortably close to a high-functioning form of autism, and the writers do not seem to be at all aware of this as they encourage us to find Napoleon to be, minimally, a bit of a weirdo, albeit a self-defined one. I was wrong about the rest. Napoleon Dynamite loves its characters a lot, loves all of their quirks, wants to see them all win. But it loves them from a very specific place, one that discourages outsiders from tapping into that love. I've heard from too many people on the film's wavelength, who've come from the sorts of places that it depicts, that this is exactly right, and these are note-perfect characters treated with dignity and affection, for me to assume that it's not true. I don't see it at all, and I find there to be something distinctly sour-tasting in how long the film lingers on its characters doubling-down on their awkwardness.

And yet, if you walk into the film looking for sweetness, as I did this time, you can tell where it's hiding. The film opens with the White Stripes' "We're Going to Be Friends", a quiet little acoustic guitar ode to childhood friendships and being nice to people, and the plot, such as it is, consists of Napoleon, Deb, and Pedro, three people with no friendships between them, forming a nice little trio of mutual support. It's very Nice - in fact, it's very Nice in a very Mormon way, though not one single thing that happens onscreen that makes that explicit. But the Hesses and Heder are Mormons, and the Church embraced and promoted the film in 2004 and has pushed it ever since, and there's a very big, smiling, sanitary quality to the film that bears out the idea that it is a movie for Mormons to enjoy, if not in any way a message film. It's clean - there's not any word harsher than "crap", there's no lasting violence, and, despite the fact that it's set in high school and includes multiple dating subplots, there is not the faintest whisper of sex. Beyond doubt, it's friendly and harmless and welcoming, but in a creepily effortful way. To my mind, anyway.

The film strains to combine all of its impulses: its celebration of those who don't fit in and those who come from the least cosmopolitan places that movies don't care about; its arch, performative approach to characters; its down-to-earth aesthetic. Nothing coheres, and the effect is almost never funny to me (there are some well-crafted visual jokes, admittedly; but I can't say that I ever once laughed at a line of dialogue). People obviously get something out of this, and I haven't the right to begrudge them that: but in Napoleon and his friends, I barely recognise human beings at all, let alone human beings I have known in my life, and without that spark of familiar feeling, I simply don't think there's any way to get on this very singular film's wavelength.

There's going to be a lot of wholly subjective, first-person claims in this review, I am sorry to say. But comedy is notoriously subjective and this is a specifically notoriously subjective comedy we have in front of us, and it is important that I lay out all my biases at the front, because the critic who feigns objectivity where he has none is an irresponsible & wicked critic. Anyway, the thing is that Napoleon Dynamite never had a chance with me from the start. Back in the summer of 2004, you may perhaps recall, there was an extraordinary fetish for the movie among the kind of high school and college students of a sufficiently adventurous bent that they'd track down indie movies in the first place, even non-threatening and wholly mainstream indies like this one. It was the quotable movie for the under-25 set, which meant that, years before I finally forced myself to sit through, it felt like I'd already seen the whole thing; and there is no hope for a comedy wherein you've already heard and not laughed at most of the jokes. It is impossible, in that kind of hyped-up environment, to experience the sense of delightfully astonished discovery that makes films like Napoleon Dynamite into word-of-mouth hits in the first place.

That being said, I looked forward, in an intellectually curious way, to seeing the film again with a decade and change of buffering from the thickest part of its faddish acclaim, to maybe have a chance to respond to it from a place of anything that wasn't ice-cold hostility. And in the end, while I still do not like Napoleon Dynamite, and I do not find it in any way funny, I certainly dislike it less. And there's stuff going on inside of it that I had previously failed to credit, though I won't swear that it's good stuff.

The film, written by husband-and-wife team Jerusha and Jared Hess - Jared also directed - is an almost entirely plotless amble around Preston, Idaho, the filmmakers' hometown. Our entry point and protagonist into this world is 16-year-old Napoleon Dynamite (Jon Heder), an exemplar of all those things we think about when the word "nerd" is spoken: tacky clothes, tunnel vision about his private obsessions, a near-complete lack of interest in communicating with other people in a normal way. His world is full of eccentrics no less insular than he, though for the most part they lack his frustrated hostility towards the world: some of the most important figures include his much older brother Kip (Aaron Ruell), who lives with him and their grandmother (Sandy Martin); Deb (Tina Marjorino), a shy entrepreneur who works odd jobs to raise money for college; Pedro (Efren Ramirez), a transfer student with an eerily unflappable mien, who becomes Napoleon's best and only real friend, and vice versa; and Rico (Jon Gries), Napoleon and Kip's uncle, who comes to watch the house while their grandma recovers from a dune buggy accident. Things don't really happen in any of their lives until almost the very end; mostly, it's just snippets of people trying to pass the time in a flyspeck like Preston, a place they've all lived so long that they don't even have the context to explain why they find it boring.

There are a lot of ways you could take this kind of anti-directional, slice-of-life storytelling; the one that Napoleon Dynamite picks is absurdist comedy, which I frankly don't think works very well. With its highly stylised performances of characters defined through their idiosyncratic interests, it's self-consciously "punchy" editing, and its squared-off compositions, Napoleon Dynamite resembles nothing so much as a Wes Anderson film, like so very many other indie movies of the early-to-mid 2000s. Except that Jared Hess and cinematographer Munn Powell, working from an ultra-relaxed, observational perspective shoot the film with a great deal of scratchy, dusty realism - the compositions might be completely indebted to Anderson, but the textures are from a wholly different mode of indie filmmaking altogether, one steeped in the documentary impulse and anxious to capture places with as much authenticity and detail as can be.

It's a unique combination, I have to give it that; I can't pretend, though, that it feels me with very much pleasure to watch it. The naturalism in the cinematography ties in with an overall laid-back approach, in which moments are paced out slowly, the actors themselves move slowly; it has the sleepy humid sensibility of, to name the first contemporaneous director who jumps to mind, David Gordon Green (though without Green's Malickian awe for the cinematic image). A hybrid Green and Anderson, two of the most celebrated indie auteurs of the early '00s, was surely going to happen, but it just as surely was going to turn into the odd duck that we have here. For me, it's a specific combination of absurd attitude and languid rhythm that absolutely murders the comedy. I can't tell the people who laugh at Napoleon Dynamite that they're wrong; funny can only be a matter of taste. But in this particular instance, I'm not even sure what's meant to be funny, I don't even see the shape of the humor: it seems like a bunch of strange, half-alien people talking in stilted ways, with Heder often launching into a braying howl of impatience with the morons around him that feels to me much too angry to ever laugh with it, or at it.

All of that being true, I have to admit that in one key respect, I had the film pegged wrong at first. Watching Napoleon Dynamite the first time felt like an exercise in complete rancidity: the Hesses seemed to hold every last one of their characters in deep contempt, looking on them as dimwitted rubes, and using Napoleon's curt sense of superiority half of the time as a tool for cutting down the rest of their cast, half of the time as a way of mocking Napoleon himself, who frequently seemed to be the butt of jokes that were nothing so much as mocking potshots at an autistic kid. I'm still not quite sure that I'm off-base with that last part: the film's concept of "socially awkward nerd" comes uncomfortably close to a high-functioning form of autism, and the writers do not seem to be at all aware of this as they encourage us to find Napoleon to be, minimally, a bit of a weirdo, albeit a self-defined one. I was wrong about the rest. Napoleon Dynamite loves its characters a lot, loves all of their quirks, wants to see them all win. But it loves them from a very specific place, one that discourages outsiders from tapping into that love. I've heard from too many people on the film's wavelength, who've come from the sorts of places that it depicts, that this is exactly right, and these are note-perfect characters treated with dignity and affection, for me to assume that it's not true. I don't see it at all, and I find there to be something distinctly sour-tasting in how long the film lingers on its characters doubling-down on their awkwardness.

And yet, if you walk into the film looking for sweetness, as I did this time, you can tell where it's hiding. The film opens with the White Stripes' "We're Going to Be Friends", a quiet little acoustic guitar ode to childhood friendships and being nice to people, and the plot, such as it is, consists of Napoleon, Deb, and Pedro, three people with no friendships between them, forming a nice little trio of mutual support. It's very Nice - in fact, it's very Nice in a very Mormon way, though not one single thing that happens onscreen that makes that explicit. But the Hesses and Heder are Mormons, and the Church embraced and promoted the film in 2004 and has pushed it ever since, and there's a very big, smiling, sanitary quality to the film that bears out the idea that it is a movie for Mormons to enjoy, if not in any way a message film. It's clean - there's not any word harsher than "crap", there's no lasting violence, and, despite the fact that it's set in high school and includes multiple dating subplots, there is not the faintest whisper of sex. Beyond doubt, it's friendly and harmless and welcoming, but in a creepily effortful way. To my mind, anyway.

The film strains to combine all of its impulses: its celebration of those who don't fit in and those who come from the least cosmopolitan places that movies don't care about; its arch, performative approach to characters; its down-to-earth aesthetic. Nothing coheres, and the effect is almost never funny to me (there are some well-crafted visual jokes, admittedly; but I can't say that I ever once laughed at a line of dialogue). People obviously get something out of this, and I haven't the right to begrudge them that: but in Napoleon and his friends, I barely recognise human beings at all, let alone human beings I have known in my life, and without that spark of familiar feeling, I simply don't think there's any way to get on this very singular film's wavelength.