This is the story of a girl

A review requested by Alex, with thanks for contributing to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

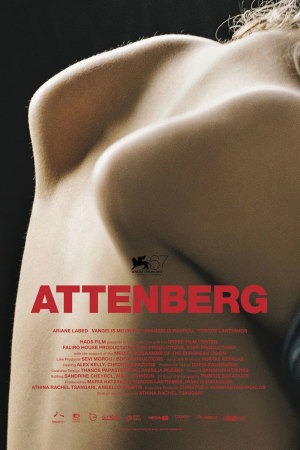

The line on 2010's Attenberg, established during its 2012 U.S. release in my hearing, but possibly older, is that it is a warped and weird and delectably perverse entry into the 21st Century's tradition of demented Greek films, and I will have to say, I really didn't see that at all. Though I also only knew about the film that it was produced by Yorgos Lanthimos, director of the titanically fucked-up Dogtooth, and features him in a small role as somebody who has what I think is simulated sex with the protagonist (also, Attenberg is the kind of film where it pays to hedge your bets over whether the sex scenes were simulated or not), and walking into very nearly any film prepped for Dogtooth Redux is going to necessarily make it seem tame.

Instead, what I got was a top-tier slice of life drama about an emotionally stilted 23-year-old, Marina (Ariane Labed), marching mirthlessly through life in a coastal city on the backside of the industrial age, while her father Spyros (Vangelis Mourikis) is steadily dying in the local hospital. If there is anything of Dogtooth in it, it would only be that both films are about young adults who have not developed sexually in a way that's normal - and even that only takes us as far as Marina being resolutely disinterested in and somewhat disgusted by physical intimacy, without it going deep into the red on the "Inappropriate and Awful" meter. Unusual, yes, and the film goes out of its way to feint at incest but it really doesn't have the heart to pretend like that's really what it wants to be on about.

The film that most tenaciously hung around my brain throughout Attenberg was, instead, Fucking Åmål, Lukas Moodysson's 1998 treatise on unformed adolescent female sexuality in a lifeless small town on the water. That film is steadily realist, while Attenberg's director, Athina Rachel Tsangari, uses realism as a vessel for what turns out to be a not very realistic movie at all. Though in any given individual shot, you'd probably assume that you were looking at something very plain and unadorned and all about people inhabiting naturalistic spaces that have barely been retouched by the filmmakers. But the emotions are quite honest, anyway: whatever else it does (and that's more than it appears to be), Attenberg is primarily an exploration into what it feels like to be the willfully closed-off Marina, who constructs a vision of human culture through her habitual viewing of nature documentaries (the film's title is a corruption of David Attenborough's surname), with her character filtered through three very different relationship with people more mature than she is, who treat her (perhaps inappropriately) like a peer. These are her father, an atheist with increasingly melancholy and sardonic thoughts on the world; her best friend Bella (Evangelia Randou), a sexually promiscuous young woman who helps Marina play-act sex in what reads as an appropriation of same-sex attraction more than an example of it; and an unnamed engineer (Lanthimos), in town on business, who enters into a sexual relationship with Marina that evolves quite slowly, and with a weird twist on eroticism. It's not every day you get to see a movie where the most striking sex scene involves a man helping a woman get dressed after they didn't even get in bed together.

As is maybe clear from all that, Attenberg lives in a peculiar valley between neorealism and something more kinked up and theatrical. And it's absolutely great. I loved Dogtooth> and I think that it's going to live longer in the memory of cinephiles (because it is better), but Attenberg has all of that film's unafraid grappling with malformed sexual psychology and aggressively casual portrayal nudity and fucking, in a friendlier, more "useful" vessel. For when all is said and done, Marina feels like a relatively normal human being with relatively normal emotions, depicted with only a little bit of irony. Attenberg is surprisingly funny in the bleakest, blackest way (mostly due to Spyros's increasingly morbid comfort with the reality that he will be dying very soon, and the quippy way he and Marina plan for that event), and its portrayal of the ways a bored 23-year-old keeps herself distracted results in a loose, shambling narrative almost entirely filled up with aimless hang-out moments. Yet the confidence with which the film moves towards its inevitable end points, and the easy rhythm with which Tsangari and editors Sandrine Cheyrol and Matthew Johnson switch between each of the three threads of Marina's life (that is, which person she's sharing scenes with), keep the film driving forward with exceptional momentum for a film in which, basically, only two things happen. I don't suppose I want to see a version of this movie that's a whole lot longer than 97 minutes, but in its current incarnation, it flies by and is surprisingly gripping.

It's not a "what happens" sort of movie, anyway, it's a "who does it happen to" movie, and Marina is a terrific character: given enough unique and even off-putting baggage in Tsangari's screenplay that she seems much too specific to stand in for All Women In Their Early 20s, which of course is exactly why she's so extraordinarily good at being exactly such a stand-in. Labed's performance is absolutely outstanding, playing the character's awkwardness and standoffish hostility in a way that's never "likable", exactly - she's not sniffing around for sympathy, certainly - but which makes Marina emerge as so coherent and comprehensible within her own head that she becomes tremendously easy to sympathise and empathise with, despite being comprised almost solely of sharp, unfriendly angles. The film gives itself over to her completely: even the framing of images by cinematographer Thimios Bakatakis is an extrapolation of Marina's mindset. Every shot in the movie is arranged on 90° angles, either directly facing the characters or directly to the side, and most of the action takes place in rigid, lateral movements, underscoring her flat, unimaginative views on what the world and people are like. When the film breaks free from this geometric precision, the sense of raw emotional abandon hits all the harder because of how conspicuously aberrant it is.

The prickly, sexually frank, physically messy film is undoubtedly more off-putting than I'm letting on, but I was onboard with it from the first moment (its most off-putting, as Bella tries to teach Marina how to kiss with mouth and tongue contortions that evoke Cronenerg). The combination of naturalism and deeply sardonic, satiric writing and formalized behavior is sufficiently unusual and well-executed that the mere energy of the film carries it rather far; that it is also an incisive study of a marvelously unusual protagonist pushes it into "great lost films of the 2010s" territory. I am horribly dismayed that it took me four years to catch up with it.

The line on 2010's Attenberg, established during its 2012 U.S. release in my hearing, but possibly older, is that it is a warped and weird and delectably perverse entry into the 21st Century's tradition of demented Greek films, and I will have to say, I really didn't see that at all. Though I also only knew about the film that it was produced by Yorgos Lanthimos, director of the titanically fucked-up Dogtooth, and features him in a small role as somebody who has what I think is simulated sex with the protagonist (also, Attenberg is the kind of film where it pays to hedge your bets over whether the sex scenes were simulated or not), and walking into very nearly any film prepped for Dogtooth Redux is going to necessarily make it seem tame.

Instead, what I got was a top-tier slice of life drama about an emotionally stilted 23-year-old, Marina (Ariane Labed), marching mirthlessly through life in a coastal city on the backside of the industrial age, while her father Spyros (Vangelis Mourikis) is steadily dying in the local hospital. If there is anything of Dogtooth in it, it would only be that both films are about young adults who have not developed sexually in a way that's normal - and even that only takes us as far as Marina being resolutely disinterested in and somewhat disgusted by physical intimacy, without it going deep into the red on the "Inappropriate and Awful" meter. Unusual, yes, and the film goes out of its way to feint at incest but it really doesn't have the heart to pretend like that's really what it wants to be on about.

The film that most tenaciously hung around my brain throughout Attenberg was, instead, Fucking Åmål, Lukas Moodysson's 1998 treatise on unformed adolescent female sexuality in a lifeless small town on the water. That film is steadily realist, while Attenberg's director, Athina Rachel Tsangari, uses realism as a vessel for what turns out to be a not very realistic movie at all. Though in any given individual shot, you'd probably assume that you were looking at something very plain and unadorned and all about people inhabiting naturalistic spaces that have barely been retouched by the filmmakers. But the emotions are quite honest, anyway: whatever else it does (and that's more than it appears to be), Attenberg is primarily an exploration into what it feels like to be the willfully closed-off Marina, who constructs a vision of human culture through her habitual viewing of nature documentaries (the film's title is a corruption of David Attenborough's surname), with her character filtered through three very different relationship with people more mature than she is, who treat her (perhaps inappropriately) like a peer. These are her father, an atheist with increasingly melancholy and sardonic thoughts on the world; her best friend Bella (Evangelia Randou), a sexually promiscuous young woman who helps Marina play-act sex in what reads as an appropriation of same-sex attraction more than an example of it; and an unnamed engineer (Lanthimos), in town on business, who enters into a sexual relationship with Marina that evolves quite slowly, and with a weird twist on eroticism. It's not every day you get to see a movie where the most striking sex scene involves a man helping a woman get dressed after they didn't even get in bed together.

As is maybe clear from all that, Attenberg lives in a peculiar valley between neorealism and something more kinked up and theatrical. And it's absolutely great. I loved Dogtooth> and I think that it's going to live longer in the memory of cinephiles (because it is better), but Attenberg has all of that film's unafraid grappling with malformed sexual psychology and aggressively casual portrayal nudity and fucking, in a friendlier, more "useful" vessel. For when all is said and done, Marina feels like a relatively normal human being with relatively normal emotions, depicted with only a little bit of irony. Attenberg is surprisingly funny in the bleakest, blackest way (mostly due to Spyros's increasingly morbid comfort with the reality that he will be dying very soon, and the quippy way he and Marina plan for that event), and its portrayal of the ways a bored 23-year-old keeps herself distracted results in a loose, shambling narrative almost entirely filled up with aimless hang-out moments. Yet the confidence with which the film moves towards its inevitable end points, and the easy rhythm with which Tsangari and editors Sandrine Cheyrol and Matthew Johnson switch between each of the three threads of Marina's life (that is, which person she's sharing scenes with), keep the film driving forward with exceptional momentum for a film in which, basically, only two things happen. I don't suppose I want to see a version of this movie that's a whole lot longer than 97 minutes, but in its current incarnation, it flies by and is surprisingly gripping.

It's not a "what happens" sort of movie, anyway, it's a "who does it happen to" movie, and Marina is a terrific character: given enough unique and even off-putting baggage in Tsangari's screenplay that she seems much too specific to stand in for All Women In Their Early 20s, which of course is exactly why she's so extraordinarily good at being exactly such a stand-in. Labed's performance is absolutely outstanding, playing the character's awkwardness and standoffish hostility in a way that's never "likable", exactly - she's not sniffing around for sympathy, certainly - but which makes Marina emerge as so coherent and comprehensible within her own head that she becomes tremendously easy to sympathise and empathise with, despite being comprised almost solely of sharp, unfriendly angles. The film gives itself over to her completely: even the framing of images by cinematographer Thimios Bakatakis is an extrapolation of Marina's mindset. Every shot in the movie is arranged on 90° angles, either directly facing the characters or directly to the side, and most of the action takes place in rigid, lateral movements, underscoring her flat, unimaginative views on what the world and people are like. When the film breaks free from this geometric precision, the sense of raw emotional abandon hits all the harder because of how conspicuously aberrant it is.

The prickly, sexually frank, physically messy film is undoubtedly more off-putting than I'm letting on, but I was onboard with it from the first moment (its most off-putting, as Bella tries to teach Marina how to kiss with mouth and tongue contortions that evoke Cronenerg). The combination of naturalism and deeply sardonic, satiric writing and formalized behavior is sufficiently unusual and well-executed that the mere energy of the film carries it rather far; that it is also an incisive study of a marvelously unusual protagonist pushes it into "great lost films of the 2010s" territory. I am horribly dismayed that it took me four years to catch up with it.