Of gods and men

"Who's that then?"

"I dunno, must be a king."

"Why?"

"He hasn't got shit all over him."

-Monty Python and the Holy Grail

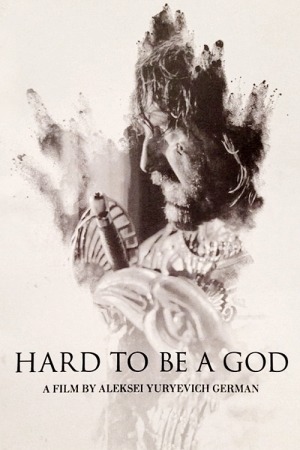

There is much shit in Hard to Be a God. That's by no means the film's most salient aspect, but it's probably the thing that's hardest to stop noticing, once you start. I have not seen any of the five previous films made by legendary Russian filmmaker Aleksei German, who spent years trying to make the film, years actually shooting it, and years completing the edit, and died in the winter of 2013, only months before the film's premiere. My understanding is that one of the commonalities between them all is that they are generally worn-down and weary in their aesthetic; in that respect, this is perhaps merely the culmination of a career's obsession. It is a film whose vision of the world is of overwhelming corruption: it is dominated with mud, shit, sweat, blood, and a general sense of filth so deep-set that a lifetime of hot showers could never get rid of it all.

Written by German and his wife Svetlana Karmalita, this is the second adaptation of the 1964 novel by brothers Arkady & Boris Strugatsky (following a West Germany-USSR co-production from 1989 which I've only learned this very minute includes Werner Herzog in its cast, so now I'll be making a priority of tracking that down in an English-friendly incarnation), which finds us on an alien planet that looks almost indistinguishable from medieval Europe. As we learn in a cursory opening narration and then never hear of again, a team of scientists from Earth have arrived and embedded themselves into the fabric of society, establishing themselves as the leaders of the native civilization (presumably through advanced technological knowledge; it's the first of many things the film takes great pleasure in leaving obscure). The leader of this team, Don Rumata (Leonid Yarmolnik) has spent much time attempting to nudge the alien society forward, as far as we thing of "forward" going in Earth terms, attempting to manipulate culture solely from within and on its own terms, without bringing all kinds of awesome spaceman technology to bear. You might say that he is a kind of a god, and executing his mission in such benighted circumstances is hard.

(Alternately, you might hear the film's title, and immediately flash to the musical number "It's Tough to Be a God" from DreamWorks Animation's The Road to El Dorado from 2000. And if you did, I look forward to seeing you in our private, shared circle of Hell).

As I understand it, without the benefit of having read the book - oh, the ignorance I'm confessing to in this review! - Hard to Be a God started its life as a semi-critical metaphorical examination of how the Soviet government sent emissaries from the cities to the country, in order to educate the illiterate peasant population in the ways of 20th Century technology and proper Communist living; the film, conceived during the Communist period, in production during Putin's first term as president, and largely completed during Medvedev's tenure, maybe has political resonances with any or all of those periods. It is certainly about the futility of leadership, iron-fisted or otherwise; Rumata might well be a god or something like it, but not a very impressive one, and he has been rather more absorbed by the squalor surrounding him than instrumental in reducing its omnipresence.

Nothing about the film is at all as clear and nice as I've just made it out: that's the result of two viewings (one baffled and entranced; one entranced and at least slightly less baffled) and a lot of reading what other people have said. The film is driven by ideas, but in the grand tradition of Soviet philosophical narrative, it doesn't want to let you have them like it's tossing out candy at a parade. This is Art Cinema at its most willful and intentionally daunting, demanding a fully engaged viewer who is all set to be as patient as it takes - for obvious reasons, the film most English-language critics have compared this Russian-made allegory in a medieval setting is Tarkovsky's Andrei Rublev, and I'd be a liar if I said that wasn't a helpful way to think about it, but it's the Hungarian Sátántangó that I kept going back to. Like that film, Hard to Be a God makes something of a sport out of its duration, always testing a little bit to see if we've exhausted ourselves; like that film, it gets uncommonly dense narrative and thematic mileage out of things that would apparently have nothing to do with narrative or theme, like camera movement and squelchy, wet production design (on the subject of obvious comparisons, formalism had nothing to do with why I first thought of Sátántangó

At a certain point, in fact, I think the best way to process Hard to Be a God is to just let it be a sensory experience, because it's an all-enveloping one. None of us, of course, know what the actual Middle Ages might have looked or sounded like, but German's crew puts in a strong bid here. The production design is such a key component of what the film is that it's credited to three people, Sergei Kokovkin, Georgiy Kropachyov, and Elena Zhukova. Their cumulative effort is one of the great large-scale movie sets of recent memory, a whole town made out of decaying wood and crudely assembled masonry, looking simultaneously ancient and hardly strong enough to have survived for two weeks without collapsing. Helping to bring this setting to life is an incredibly involving sound mix, one that's certainly exaggerated and poppy far beyond the point of naturalism (as I understand it, the film was shot entirely without sound, so that every last noise and word we hear was crafted in post-production), but it creates a feeling of intense over-stimulation that feels, as it were, realer than real. The impression isn't that we're taking the place of an observer who's part of this world, but an observer who is brand new to it, and is instantaneously disoriented by it. Which applies as much to the murky way the story expresses itself as to the heightened mise en scène, maybe.

If part of the film's appeal as a kind of hypnotic spectacle is this overclocked realism, another part is the artful, very showy unrealism of its cinematography, executed by Vladimir Ilin and Yuri Klimenko. This is entirely in black and white: sharp, glowing black-and-white, that intermixes shots in which everything is in blurry greyscale with shots so high contrast that it nearly resembles a Frank Miller comic. It's at once dreamily impressionistic and uncomfortably textural: the monochromatic images draw maximum attention to the slightest changes in the textures of all the things we see.

Just as impressive is the way that the film employs its long takes. Very long takes at times, but ones that hide themselves by consciously and purposefully shifting perspective and position in ways that mimic relatively straightforward editing patterns. It's a way of further messing with our sense of stability, of course, as well as constantly shifting our focus while reinforcing spatial continuity. The film's world is highly interconnected; it depicts a very fleshed-out society teeming with people as they interact within a certain environment that dictates how those interactions can play out. The way the film is shot allows us to experience different aspects of that society, while also stressing its unity. The very curious result is a film that seems to have only three characters, and Rumata is the only one who is a human being (Yarmolnik gives a terrific performance, too, hard and miserable with just enough arch dignity that you can see where, once upon a time, that "god" appellation came from): the others are The Town and The People, and the three-way interplay is the heart of the film.

Hard to Be a God is seemingly built out of contradictions: the way the cinematography divides and unifies simultaneously is one, as is the heightened sense of the real through wholly unreal aesthetics. The narrative and philosophy are also powered by contradictions: between the desire to do good for people, and only being able to perpetuate ugliness; between the depiction of humans as rational figures with great potential, and as howling animals living in filth. The experience of watching it is another contradiction: it is exhilarating and wholly beautiful, while also being deeply unpleasant and unattractive. The last of these is what makes it an exceptionally hard thing to ever recommend to anybody, but I can't shake the feeling that it's one of the most important films of the 2010s. Check back in with me in three or ten or forty years.