In the jungle

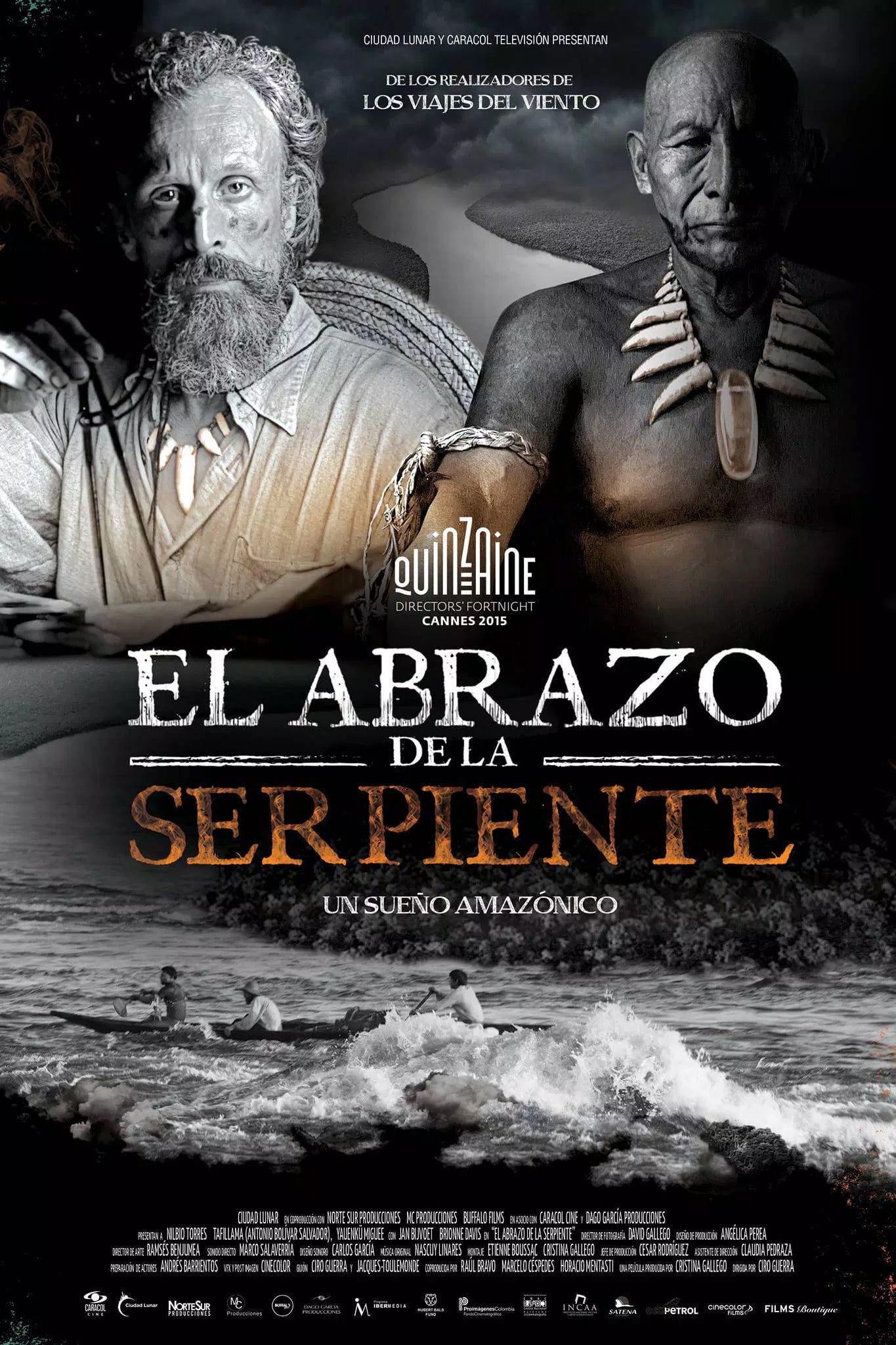

There's something deliciously off-kilter about folding a story about the abuse and genocide of indigenous South American cultures into what amounts to a mismatched buddy comedy (minus any jokes), and for that alone, Embrace of the Serpent - Colombia's first-ever nominee in the Best Foreign Language Film category at the Oscars - would deserve our full attention. Add to that how the film does this twice in two parallel narratives, each centered around the same man at two widely different points in his life; add as well that it ends up as a period costume drama biopic, and lastly add that it has as one of its major sequences a horror-movie layover in a messianic cult leader's compound that plays like Fellini remaking Apocalypse Now. Now we're getting someplace really special.

The film is the third feature by director Ciro Guerra, co-writing a screenplay by Jacques Toulemonde Vidal that's based on the diaries of two white ethnographers, Theodor Koch-Grunberg of Germany and Richard Evans Schultes of the United States. Fictionalised iterations of both of those people show up in the movie (played by Jan Bijvoet and Brionne Davis, respectively), in both cases requiring the guidance of Karamakate, the last surviving member of a tribe wiped out by European rubber plantations, played by Nilbio Torres when he encounters Theo in 1909, by Antonio Bolivar when he is tracked down by Evan in 1940. In both cases, the white man is in need of a rare flower that Karamakate alone can hunt down, Theo because he is dying of some hideous tropical disease, Evan because he's collecting data on the traditional healing qualities of plants and found his curiosity piqued by reading Theo's old journals. In 1909, Karamakate snipes at Theo, and Theo's more thoroughly Westernised native guide Manduca (Yauenkü Migue) with sharp and on-point criticisms of Europeans' endless ability to fuck things up; in 1940, he is reflective and tired, and much gentler with Evan, but still unwilling to let the American lose sight of the fact that he's an unwanted interloper.

It all sounds schematic when it's laid out like that, but in the execution, Embrace of the Serpent is a great deal more fluid and elliptical than that. It's built by feeling and intuition more than labored script parallels - for example, it never actually gets around to confirming that Karamakate is the same person in both time periods until most of the way to the end, and the drift from 1909 to 1940 and back is never done for what we'd mostly consider self-evident reasons. There's absolutely no hint that the film "actually" takes place in 1940, and is flashing back to 1909, nor do Guerra and cinematographer David Gallego visually distinguish the two time periods, capturing everything in the same jaw-droppingly gorgeous, contrasty black and white. Nor does anything onscreen help to make any kind of distinction: the two white men are the only visual component of the film that denotes any particular time period whatsoever. So the whole movie ends up blurring into an eternal present, one that only seems by sheer accent to take place on either side of a 31-year-span (and it also feels mostly incidental that the more modern of the storylines is set 75 years prior to the film's release).

Embrace of the Serpent derives a lot from its perpetual now-ness, and also contrasts it with an almost unfathomable sense of age and detachment; the contrast between the two moods is a driving force in the film. Torres plays young Karamakate with punchy, contemporary energy, sharply opposed to Bijvoet's creaky way of playing Theo in such a theatrical way that it feels like he's trying to situate the film another hundred years further in the past; Bolivar's older Karamakate has absorbed some of that creakiness, but filters it through an interior-looking style of acting that comes off as maybe the most modern thing in the film. The fact that this is all in black and white obviously gives it a sense of timelessness, and yet the harshness and cleanness of the cinematography never leaves us with any illusion that we're looking at a meaningfully old movie.

What this all lends to the film is a thoroughly disconcerting mixture of awareness of our separation from the content of the film (which is, after all, about knowledge, culture, and people who have been irrevocably lost), mixed indivisibly from a sense that this is taking place right now, this minute, in front of us (since the film is, after all, about desperately trying to find some way to keep alive wisdom and experience in the face of destruction that's surely coming any moment in the future). In principle, all of this should be at least somewhat obnoxious: it's basically an ethnographic piece based on the perspective of aliens to the culture being depicted (the film notes in a chillingly dispassionate title card at the end that Koch-Grunberg and Schultes's diaries represent the only documentary record of the peoples they interacted with), but there are very, very few dramatic ethnographic films in my experience that seem so completely unmodulated by an outsider's perspective. It undoubtedly helps matters that Karamakate is so much more interesting than the sickly Theo or the callow Evan, and that the two actors playing him are given so much more space for interesting, sophisticated personality-building.

If all that makes the film sound medicinal, or God forbid, prestigious (it is an Oscar-nominee, after all), fear not! Embrace of the Serpent is certainly more interesting than that, and unabashedly eager to try out weird and unpredictable artistry. High-contrast black and white movies aren't exactly commonplace, nor are films that smudge their plots like this. At times, it falls into the expected: a climactic drugged-up vision is striking but not because it is in any way unusual, and the whole matter of that messianic cult, while astonishingly unnerving both in terms of writing and the bleak visuals that come into play (there's a wide shot from a high angle through a window that freaked me out more than it had any apparent reason to), has the unmistakable tang of "let's throw something batshit crazy at the movie now, because why not!" But for the most part, this is nervy, ambitious filmmaking, fully deserving its top prize from the 2015 Cannes Directors' Fortnight. It is not always perfect, and every so often it leans on its themes a bit more heavily than I tend to care for, but this is uncommonly close that that "from the visionary mind of" stuff that they talk about sometimes, and if Guerra wants to do exactly the same next time around, I'm all for it.

The film is the third feature by director Ciro Guerra, co-writing a screenplay by Jacques Toulemonde Vidal that's based on the diaries of two white ethnographers, Theodor Koch-Grunberg of Germany and Richard Evans Schultes of the United States. Fictionalised iterations of both of those people show up in the movie (played by Jan Bijvoet and Brionne Davis, respectively), in both cases requiring the guidance of Karamakate, the last surviving member of a tribe wiped out by European rubber plantations, played by Nilbio Torres when he encounters Theo in 1909, by Antonio Bolivar when he is tracked down by Evan in 1940. In both cases, the white man is in need of a rare flower that Karamakate alone can hunt down, Theo because he is dying of some hideous tropical disease, Evan because he's collecting data on the traditional healing qualities of plants and found his curiosity piqued by reading Theo's old journals. In 1909, Karamakate snipes at Theo, and Theo's more thoroughly Westernised native guide Manduca (Yauenkü Migue) with sharp and on-point criticisms of Europeans' endless ability to fuck things up; in 1940, he is reflective and tired, and much gentler with Evan, but still unwilling to let the American lose sight of the fact that he's an unwanted interloper.

It all sounds schematic when it's laid out like that, but in the execution, Embrace of the Serpent is a great deal more fluid and elliptical than that. It's built by feeling and intuition more than labored script parallels - for example, it never actually gets around to confirming that Karamakate is the same person in both time periods until most of the way to the end, and the drift from 1909 to 1940 and back is never done for what we'd mostly consider self-evident reasons. There's absolutely no hint that the film "actually" takes place in 1940, and is flashing back to 1909, nor do Guerra and cinematographer David Gallego visually distinguish the two time periods, capturing everything in the same jaw-droppingly gorgeous, contrasty black and white. Nor does anything onscreen help to make any kind of distinction: the two white men are the only visual component of the film that denotes any particular time period whatsoever. So the whole movie ends up blurring into an eternal present, one that only seems by sheer accent to take place on either side of a 31-year-span (and it also feels mostly incidental that the more modern of the storylines is set 75 years prior to the film's release).

Embrace of the Serpent derives a lot from its perpetual now-ness, and also contrasts it with an almost unfathomable sense of age and detachment; the contrast between the two moods is a driving force in the film. Torres plays young Karamakate with punchy, contemporary energy, sharply opposed to Bijvoet's creaky way of playing Theo in such a theatrical way that it feels like he's trying to situate the film another hundred years further in the past; Bolivar's older Karamakate has absorbed some of that creakiness, but filters it through an interior-looking style of acting that comes off as maybe the most modern thing in the film. The fact that this is all in black and white obviously gives it a sense of timelessness, and yet the harshness and cleanness of the cinematography never leaves us with any illusion that we're looking at a meaningfully old movie.

What this all lends to the film is a thoroughly disconcerting mixture of awareness of our separation from the content of the film (which is, after all, about knowledge, culture, and people who have been irrevocably lost), mixed indivisibly from a sense that this is taking place right now, this minute, in front of us (since the film is, after all, about desperately trying to find some way to keep alive wisdom and experience in the face of destruction that's surely coming any moment in the future). In principle, all of this should be at least somewhat obnoxious: it's basically an ethnographic piece based on the perspective of aliens to the culture being depicted (the film notes in a chillingly dispassionate title card at the end that Koch-Grunberg and Schultes's diaries represent the only documentary record of the peoples they interacted with), but there are very, very few dramatic ethnographic films in my experience that seem so completely unmodulated by an outsider's perspective. It undoubtedly helps matters that Karamakate is so much more interesting than the sickly Theo or the callow Evan, and that the two actors playing him are given so much more space for interesting, sophisticated personality-building.

If all that makes the film sound medicinal, or God forbid, prestigious (it is an Oscar-nominee, after all), fear not! Embrace of the Serpent is certainly more interesting than that, and unabashedly eager to try out weird and unpredictable artistry. High-contrast black and white movies aren't exactly commonplace, nor are films that smudge their plots like this. At times, it falls into the expected: a climactic drugged-up vision is striking but not because it is in any way unusual, and the whole matter of that messianic cult, while astonishingly unnerving both in terms of writing and the bleak visuals that come into play (there's a wide shot from a high angle through a window that freaked me out more than it had any apparent reason to), has the unmistakable tang of "let's throw something batshit crazy at the movie now, because why not!" But for the most part, this is nervy, ambitious filmmaking, fully deserving its top prize from the 2015 Cannes Directors' Fortnight. It is not always perfect, and every so often it leans on its themes a bit more heavily than I tend to care for, but this is uncommonly close that that "from the visionary mind of" stuff that they talk about sometimes, and if Guerra wants to do exactly the same next time around, I'm all for it.