Universal Horror: Out of sight, out of his mind

The Universal horror movie is at heart a pre-WWII phenomenon; after The Wolf Man, released less than a week after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, the studio's genre films would never rise above "decent enough", and usually didn't even hit that threshold, until they finally gave up making them in the middle of the decade. Things were never worse than in 1944, when Universal released four films, three of them among the worst examples of horror in the history of the big studios up to that point: the thoroughly derivative The Mummy's Ghost and The Mummy's Curse were absolute dreck, slapdash B-filmmaking that oozed contempt for itself and its audience, and House of Frankenstein is even worse, disjointed gobbets of storytelling good for little else than besmirching the already tattered reputations of the studio's Big 3 monsters.

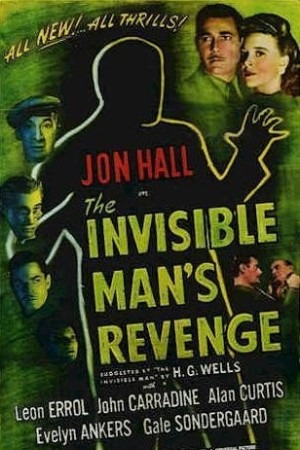

With that kind of context surrounding it, The Invisible Man's Revenge looks pretty damn good, almost. At the very least, it can't be accused of the sin common to all three of its stablemates, that it doesn't give a shit about telling any kind of unique story: if anything, the film's worst element is how much story it's trying to get through. This return to horror from the comedy of The Invisible Woman and the goofy spy adventures of Invisible Agent is no kind of retread at all, but a story that looks at the combined efforts of all four "Invisible" films preceding it, and decides that the right thing to do will be to resemble none of them whatsoever.

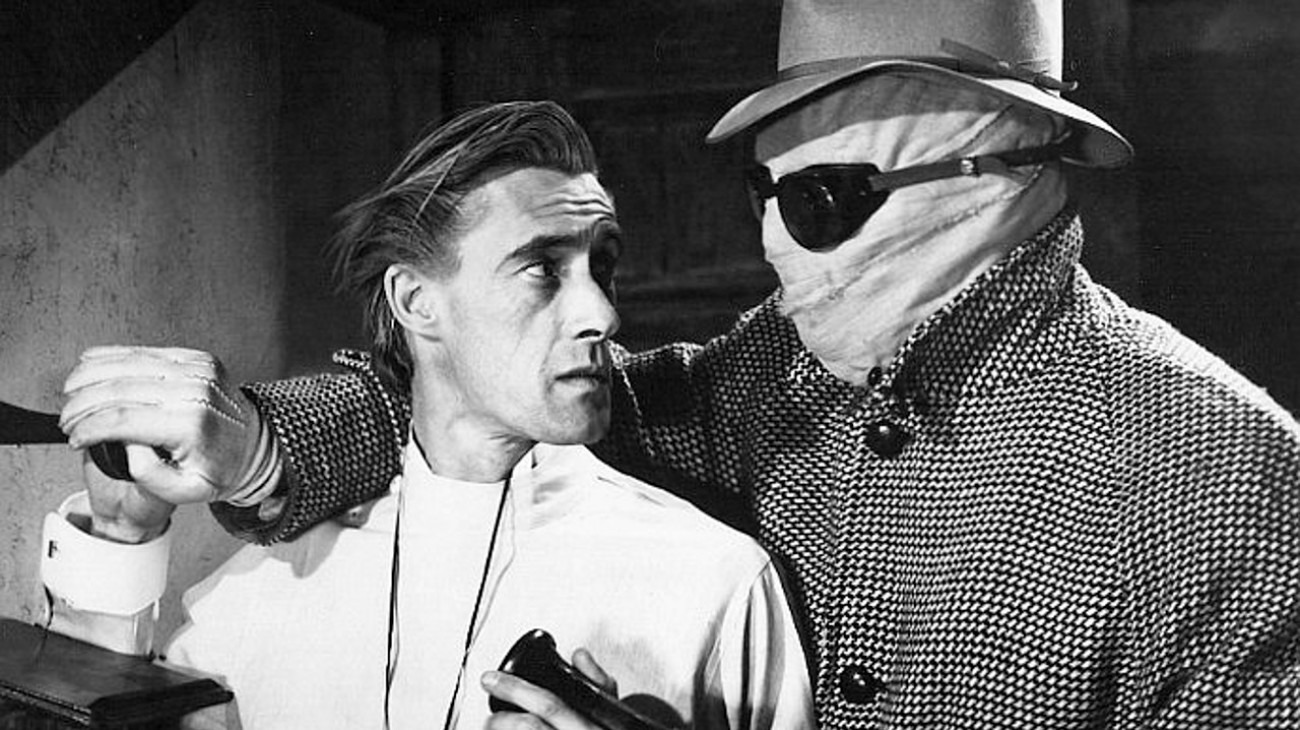

The title is no mere flight of rhetorical fancy: revenge is the life's blood of this story, written by Universal's Sherlock Holmes specialist, Bertram Millhauser. We jump right into it in the very first scene, which posits in screaming headlines that a bona-fide crazy psycho nutjob by the name of Robert Griffin (Jon Hall, who was also Invisible Agent's invisible agent) has escaped from the institution in Africa where he was meant to be safely held away for the rest of time, and of course the first thing he does is to sneak back into England from whence he came many years ago, hunting for his old colleagues, the Herricks. Seems that once upon a time, he and the couple, Irene (Gale Sondergaard) and Jasper (Lester Matthews) were trying to make their fortunes in diamonds out in British Tanganyika, when a possibly on-purpose accident left Griffin seemingly dead and the Herricks in sole control of their diamond mine. After wandering the continent with amnesia, Griffin has finally come back to his senses, and he wants his share of the money. The only problem is, Jasper has been entirely terrible at keeping that money all in one place, and the Herricks now totter on the edge of going broke. In a panic, Irene serves Griffin a drugged drink, and they throw him out in a blind haze, causing him to very nearly drown.

Griffin is saved by the poor drunk Herbert Higgins (Leon Errol), who decides to use Griffin's information to blackmail the Herricks rather than help the crazy bastard out himself. This turns things even worse for Griffin, who is at his wits' end when he happens to stumble across a charming old loony scientist by the name of Peter Drury (John Carradine). Drury, wouldn't you know, has figured out how to turn animals invisible, and he's been itching to try his technique out on a human, only no human has been reduced to such desperate circumstances to take on his madcap scheme. Griffin, naturally enough, leaps at the chance to have the ability to wreak vengeance on the Herricks, now that they've maybe intentionally tried to kill him twice, and all the world without being seen. His subsequent reign of terror attracts the expected attention from the local police, and an intrepid local reporter by the name of Mark Foster (Alan Curtis) - who, as good fate has it, has just recently started courting the Herricks' daughter, Julie (Evelyn Ankers), who has quickly become the focus of Griffin's obsessions.

That's the mercilessly pared-down version of the first half of the 78-minute movie, which is as much to say that The Invisible Man's Revenge is an enormously busy motion picture. Maybe not to its benefit - probably not to its benefit, though of course I'm we'd all rather have the curlicues of betrayal and madness, and the multiplicity of plotlines, that's on display in this film, than the miserable smallness of The Mummy's Curse. Nothing in this movie makes all that much sense - the layover with that wretch Higgins in particular feels like Millhauser or somebody was trying the relate the plot of a particularly vivid, realistic dream and it got tangled up with the screenplay - and much of it is left frustratingly vague: just how culpable are the Herricks, anyway? But there's all lot of urgency, anyway, and if that's the best thing we're going to get from the studio worker bees still toiling to put horror movies together at this late date, well, it could surely be much worse. Director Ford Beebe (for whom this represents, impossibly, his closest approach to A-level filmmaking) fully commits to the hectic pacing of the movie, though in a really specific, peculiar way: he moves the actors through each scene with a great deal more attention to the scene itself than to the flow between them. They are pieced together like individual playlets, each with a miniaturized conflict and set of goals all its own - the net result should feel absolutely horrible, yet somehow it doesn't; it gives the drama a sense of moment-by-moment conflict that the overall whirlwind of the movie mightn't be able to achieve on its own.

Along the way, the film indulges in yet more of the series' customarily great visual effects, courtesy of John P. Fulton: a scene in which Drury brings a dog back to visibility is astonishing not just for the fact that the ability to stage it so faultlessly existed in 1944, but also that the censors at the Hays Office didn't lose their damned minds when they saw it. Later on, there's a marvelous scene in which the invisible Griffin dips his arm into an aquarium, displacing the water in a most unnerving, unnatural way; he subsequently splashes the water onto his face, which then becomes partially visible, like a melting wax figure suspended in space, a look of deep cruelty on his features. It is, a mere five movies in, the first time that this horror franchise does something genuinely and deeply horrifying.

Overall, though, the effects are lower in ambition and creativity than in any film since the first Invisible Man, where just having the effects in the first place was ambitious enough. The other big showcase scene, in which Griffin puckishly screws around with darts, is absurdly hokey-looking, and absolutely interminable as a comic interjection that hasn't the smallest sense of humor to its credit. At a certain point, all that manic pacing runs out, and the films ends in its most insipd run of scenes, with a lot of fussy business and shameless contrivances puffing out the film's last 20 minutes - not an minor portion of the whole, mind you.

Exacerbating matters, the cast is almost uniformly banal. Hall's attempts to play an insane menace are slightly less dull than his joshing portrayal of a different Griffin in Invisible Agent, but we're a long way from Claude Rains and Vincent Price. Leon Errol is scuzzy enough to make more of an impression than the vanilla Curtis and Ankers, or the campy Sondergaard, but he's barely in the movie. The only human onscreen who really threatens to make The Invisible Man's Revenge a great deal of fun to watch is Carradine, in one of the standout moments of an infamously erratic career - you never know if you're going to get deliriously hammy Carradine, or stiff and petulant Carradine, but Drury finds us in the company of the exceedingly rare subtle and graceful Carradine. It helps that the role is one of the most fascinating "tampering in God's domain" scientists of the '40s: thoughtful and reflective, with a clear moral backbone, making choices from a position of great consideration rather than hubris. The only madness to this mad doctor is present as a little twinkle in Carradine's eye; beyond that, he's actually quite a dignified, rock-steady figure, and the actor thrives in the presence of such unexpected complexity.

He's ushered out of the film rather suddenly, though, with a lot of movie left, and oh, how The Invisible Man's Revenge suffers for his absence. There's nobody to root for, which is part of a problem; there's nobody interesting enough to want to watch them even if we're not rooting for them, which is all of a problem. For a film made during the waning years of classic Universal horror, it's got a lot going for it in terms of atmosphere (the lakeside where Griffin nearly meets his early end is one of the last great locations in the studio's horror canon), the effects hold up, and it's not aching with cheapness, like all of the latter mummy films so painfully do. Even so, it simply doesn't land: the whole in this case is less than the sum of its parts, and the last serious invisible man film for nearly a half-century proves to be rather disappointingly tedious to get through.

Reviews in this series

The Invisible Man (Whale, 1933)

The Invisible Man Returns (May, 1940)

The Invisible Woman (Sutherland, 1940)

Invisible Agent (Marin, 1942)

The Invisible Man's Revenge (Beebe, 1944)

Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man (Lamont, 1951)

With that kind of context surrounding it, The Invisible Man's Revenge looks pretty damn good, almost. At the very least, it can't be accused of the sin common to all three of its stablemates, that it doesn't give a shit about telling any kind of unique story: if anything, the film's worst element is how much story it's trying to get through. This return to horror from the comedy of The Invisible Woman and the goofy spy adventures of Invisible Agent is no kind of retread at all, but a story that looks at the combined efforts of all four "Invisible" films preceding it, and decides that the right thing to do will be to resemble none of them whatsoever.

The title is no mere flight of rhetorical fancy: revenge is the life's blood of this story, written by Universal's Sherlock Holmes specialist, Bertram Millhauser. We jump right into it in the very first scene, which posits in screaming headlines that a bona-fide crazy psycho nutjob by the name of Robert Griffin (Jon Hall, who was also Invisible Agent's invisible agent) has escaped from the institution in Africa where he was meant to be safely held away for the rest of time, and of course the first thing he does is to sneak back into England from whence he came many years ago, hunting for his old colleagues, the Herricks. Seems that once upon a time, he and the couple, Irene (Gale Sondergaard) and Jasper (Lester Matthews) were trying to make their fortunes in diamonds out in British Tanganyika, when a possibly on-purpose accident left Griffin seemingly dead and the Herricks in sole control of their diamond mine. After wandering the continent with amnesia, Griffin has finally come back to his senses, and he wants his share of the money. The only problem is, Jasper has been entirely terrible at keeping that money all in one place, and the Herricks now totter on the edge of going broke. In a panic, Irene serves Griffin a drugged drink, and they throw him out in a blind haze, causing him to very nearly drown.

Griffin is saved by the poor drunk Herbert Higgins (Leon Errol), who decides to use Griffin's information to blackmail the Herricks rather than help the crazy bastard out himself. This turns things even worse for Griffin, who is at his wits' end when he happens to stumble across a charming old loony scientist by the name of Peter Drury (John Carradine). Drury, wouldn't you know, has figured out how to turn animals invisible, and he's been itching to try his technique out on a human, only no human has been reduced to such desperate circumstances to take on his madcap scheme. Griffin, naturally enough, leaps at the chance to have the ability to wreak vengeance on the Herricks, now that they've maybe intentionally tried to kill him twice, and all the world without being seen. His subsequent reign of terror attracts the expected attention from the local police, and an intrepid local reporter by the name of Mark Foster (Alan Curtis) - who, as good fate has it, has just recently started courting the Herricks' daughter, Julie (Evelyn Ankers), who has quickly become the focus of Griffin's obsessions.

That's the mercilessly pared-down version of the first half of the 78-minute movie, which is as much to say that The Invisible Man's Revenge is an enormously busy motion picture. Maybe not to its benefit - probably not to its benefit, though of course I'm we'd all rather have the curlicues of betrayal and madness, and the multiplicity of plotlines, that's on display in this film, than the miserable smallness of The Mummy's Curse. Nothing in this movie makes all that much sense - the layover with that wretch Higgins in particular feels like Millhauser or somebody was trying the relate the plot of a particularly vivid, realistic dream and it got tangled up with the screenplay - and much of it is left frustratingly vague: just how culpable are the Herricks, anyway? But there's all lot of urgency, anyway, and if that's the best thing we're going to get from the studio worker bees still toiling to put horror movies together at this late date, well, it could surely be much worse. Director Ford Beebe (for whom this represents, impossibly, his closest approach to A-level filmmaking) fully commits to the hectic pacing of the movie, though in a really specific, peculiar way: he moves the actors through each scene with a great deal more attention to the scene itself than to the flow between them. They are pieced together like individual playlets, each with a miniaturized conflict and set of goals all its own - the net result should feel absolutely horrible, yet somehow it doesn't; it gives the drama a sense of moment-by-moment conflict that the overall whirlwind of the movie mightn't be able to achieve on its own.

Along the way, the film indulges in yet more of the series' customarily great visual effects, courtesy of John P. Fulton: a scene in which Drury brings a dog back to visibility is astonishing not just for the fact that the ability to stage it so faultlessly existed in 1944, but also that the censors at the Hays Office didn't lose their damned minds when they saw it. Later on, there's a marvelous scene in which the invisible Griffin dips his arm into an aquarium, displacing the water in a most unnerving, unnatural way; he subsequently splashes the water onto his face, which then becomes partially visible, like a melting wax figure suspended in space, a look of deep cruelty on his features. It is, a mere five movies in, the first time that this horror franchise does something genuinely and deeply horrifying.

Overall, though, the effects are lower in ambition and creativity than in any film since the first Invisible Man, where just having the effects in the first place was ambitious enough. The other big showcase scene, in which Griffin puckishly screws around with darts, is absurdly hokey-looking, and absolutely interminable as a comic interjection that hasn't the smallest sense of humor to its credit. At a certain point, all that manic pacing runs out, and the films ends in its most insipd run of scenes, with a lot of fussy business and shameless contrivances puffing out the film's last 20 minutes - not an minor portion of the whole, mind you.

Exacerbating matters, the cast is almost uniformly banal. Hall's attempts to play an insane menace are slightly less dull than his joshing portrayal of a different Griffin in Invisible Agent, but we're a long way from Claude Rains and Vincent Price. Leon Errol is scuzzy enough to make more of an impression than the vanilla Curtis and Ankers, or the campy Sondergaard, but he's barely in the movie. The only human onscreen who really threatens to make The Invisible Man's Revenge a great deal of fun to watch is Carradine, in one of the standout moments of an infamously erratic career - you never know if you're going to get deliriously hammy Carradine, or stiff and petulant Carradine, but Drury finds us in the company of the exceedingly rare subtle and graceful Carradine. It helps that the role is one of the most fascinating "tampering in God's domain" scientists of the '40s: thoughtful and reflective, with a clear moral backbone, making choices from a position of great consideration rather than hubris. The only madness to this mad doctor is present as a little twinkle in Carradine's eye; beyond that, he's actually quite a dignified, rock-steady figure, and the actor thrives in the presence of such unexpected complexity.

He's ushered out of the film rather suddenly, though, with a lot of movie left, and oh, how The Invisible Man's Revenge suffers for his absence. There's nobody to root for, which is part of a problem; there's nobody interesting enough to want to watch them even if we're not rooting for them, which is all of a problem. For a film made during the waning years of classic Universal horror, it's got a lot going for it in terms of atmosphere (the lakeside where Griffin nearly meets his early end is one of the last great locations in the studio's horror canon), the effects hold up, and it's not aching with cheapness, like all of the latter mummy films so painfully do. Even so, it simply doesn't land: the whole in this case is less than the sum of its parts, and the last serious invisible man film for nearly a half-century proves to be rather disappointingly tedious to get through.

Reviews in this series

The Invisible Man (Whale, 1933)

The Invisible Man Returns (May, 1940)

The Invisible Woman (Sutherland, 1940)

Invisible Agent (Marin, 1942)

The Invisible Man's Revenge (Beebe, 1944)

Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man (Lamont, 1951)

Categories: horror, science fiction, the cinema of wwii, thrillers, universal horror