A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away...

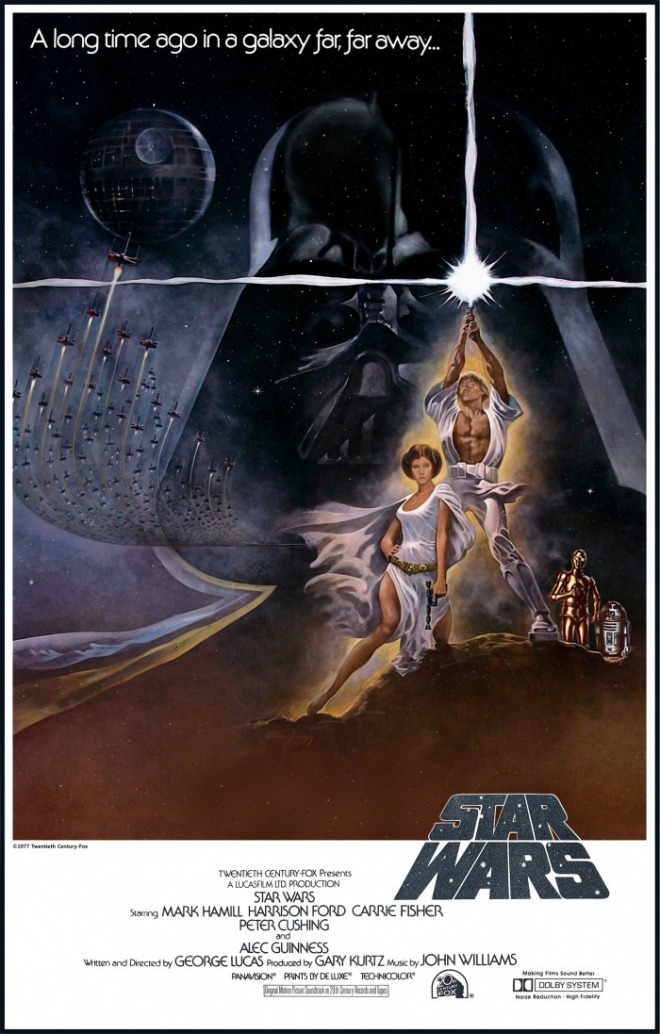

The focus of this review being its subject's position in the context of filmmaking in 1977, it is not based upon the series of "Special Edition" re-releases in theaters and on home video that have routinely happened since 1997. Instead, I take as my source material the "Despecialized Edition" reconstruction by fan editor Harmy of something akin to the original 1977 release. Legality notwithstanding, it is at present the closest we have to the original theatrical cut of a movie whose original theatrical cut was one of the defining cultural events of the 20th Century. My conscience is clear.

Let us attempt a mental exercise of incredible difficulty: dearest readers, I have faith that you can follow me, though it will be a struggle for us all. Let us disregarded the accumulated knowledge of nearly four decades - of three wholly distinct generations of filmgoers - and of the subsequent history of the film industries of every nation - let us attempt to intellectually locate ourselves in the summer of 1977, and try to imagine what we might think of Star Wars as if it was nothing but a movie. As if it was no more obviously important than the "killer nature" flick Day of the Animals or the Mummad Ali self-starring biopic The Greatest, either one of which we might just as easily have decided to check out on this hotter-than-average weekend of 25 May.

What do we find, if we strip away the accretions of iconic sounds and images, and the foreknoweldge of its many sequels and the almost uncountable number of films copying it in some way, and the awareness that this one film fundamentally changed the way commercial movies would be marketed thereafter? What is this film, in and of itself, and how does it work? These are terrifying questions to consider, but let us please do our best.

Now the reason I think it's most important to force ourselves into this 1977 mindset, beyond the fact that considering the film-as-film really is just so much more pleasurable and revelatory than considering the film-as-icon, is that it allows us to step back from the tediousness of received wisdom about Star Wars and its place in history. As everybody knows, this film and 1975's Jaws are the mean ol' popcorn films that made too much money and ruined the New Hollywood Cinema all by themselves without any other cultural contexts that need to be looked at. But for my part, I think it's much more interesting to consider how those films fit into the filmmaking culture of their time, rather than how they murdered it, or whatever. I of course admit that one can't make the claim that Star Wars is meaningfully part of the New Hollywood without having a sense of consciously swimming against orthodoxy (it's not obviously New Hollywood in the same way that Jaws is, once you decide to stop hating Jaws for existing), but that doesn't mean that it can't also be kind of true.

For one thing, try as we might want to, it doesn't make sense to forbid George Lucas from his generation of directors, since one of the primary things he brings to Star Wars is the sense of heightened film literacy and especially the awareness of film history that are one of the key aspects of '70s American filmmaking. As I'm sure we're all aware by now, Star Wars is really just a remake of Kurosawa Akira's 1958 jidaigeki adventure The Hidden Fortress, seasoned with elements of the old Flash Gordon serial, but that's in and of itself the dream project of an unapologetic film buff. Besides, it's a perfectly satisfying remake of The Hidden Fortress at that, filtering Kurosawa's Western-leaning but essentially Japanese aesthetic back through the quintessentially American giddiness that Kurosawa was replying to in the first place.

But it goes deeper than just "I went to film school!" influences. It's a fundamentally daft thing to say about a space fantasy with laser swords and wizards, but there's a basis of working class realism that sets Star Wars apart from most of the popcorn films it birthed, including its own sequels. For a huge portion of its first half - and by the way, I assume everyone is okay if I don't even nod to a plot summary, right? It's Star Wars, for chrissakes. So hopefully I can just say "everything before they take off from Mos Eisley, which happens 53 minutes into the 121-minute film", and you don't need more to go on than that. Because that's the point I have in mind when I talk about the first half, which is surprisingly grounded and thoroughly non-mythic.

The relatively low budget afforded to the film by 20th Century Fox (convinced that it was going to flop) necessitated some of that, I am sure. Still, it's striking to have a sense of the Star Wars universe and then go back to see how much of it takes place in some sandy crap corner of nowhere, one that's frankly not very attractive. Star Wars is one of the key films in popularising the "used future" aesthetic that would dominate much of science fiction cinema in the years that followed: everything we see, from the bleached white corridors of the first spaceship to the gunmetal interiors of the Death Star, has a distinctly banged-about utilitarian look, but that's never truer than in the scenes set in the Tatooine backwater where Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) suffers sullenly in the manner of bored teen boys since time immemorial. Nothing in the film looks new: the habitations look like they were just barely carved out of the desert, and the desert immediately set itself to swallowing them back up; the giant sandcrawler that the scavenging Jawas sell their after-market droids from has the definite appearance of being more rust than metal. John Barry's production design is fucking tired, with none of the gleam of pulp sci-fi, only a sense of everything being so shitty that everybody stopped paying attention to how shitty it is, and Gilbert Taylor's grainy cinematography, fully embracing the nature of '70s film stock to make everything look brown, adds a disarming sense of raw realism.

It's the film that famously made everybody finally stop thinking about Watergate and Vietnam; and yet it absolutely subscribes to the worn-out sensibility that blanketed American filmmaking in the wake of those societal schisms. It just does so more at the level of visuals and setting than in its narrative.

All of that being said, let's please not bury the fact that Star Wars is still a huge crowdpleaser, and it's quite easy to understand why audiences in '77 took it that way. It is a triumph of spectacular cinema, quite literally from the first shot after the expository crawl ends: the shot of an Imperial Star Destroyer purring angrily over our heads as it moves forward in all its dumbfounding hugeness is one of the great opening scenes in all of popcorn movies. I might even go farther, and say that all of the subsequent history of American blockbuster filmmaking is a response to that Star Destroyer, and the way it is framed to completely dominate our perception, and the way that it uses bleeding-edge visual effects to suck us into the film's reality. That the shot retains its primordial impact even now is almost beyond belief; it must have been a genuinely transformative experience when it was new and unprecedented.

It's worth lingering a bit on how the film works to make its overwhelming sensory impact, because Star Wars represents one of the great achievements in history of assembling a population of terrific craftspeople to build a movie, and Lucas and producer Gary Kurtz proved to be masters at picking the right names, more than at being storytellers, maybe. The film makes its impact through the accumulation of details, like Ben Burtt's sound effects (go ahead, make the lightsaber noise; now remind yourself that once upon a time, somebody had to consciously decide that's what it should sound like), or John Dykstra's astonishing special effects, the most weighty, plausible spaceships that had ever been seen in the movies and the first time since 2001: A Space Odyssey nine years earlier that filmmakers seem to have genuinely cared about sinking so much time into a physically authentic (ignoring the improbable physics) depiction of space. Hell, even the second unit photographers included among their number Carroll Ballard and Tak Fujimoto.

Of course, the most famous of the offscreen collaborators on Star Wars is composer John Williams, and it's no exaggeration to declare him as the individual human most responsible for the film's effect. Star Wars is preposterously laden with music, wonderfully invigorating and endlessly iconic music - I do not know what percentage of the film has some manner of instrumentation underneath the action, but it is surely a very high number. Famously, Williams borrowed the idea of leitmotif, specific cues attached to specific characters or concepts, from the operas of Richard Wagner; it's only a small jump to accuse Star Wars of behaving like an opera itself, where the constant fluctuation of music or even just tuneless sub-musical atmosphere (as in the tractor beam deactivation) guides our response to the film at a level totally divorced from the plot and imagery. Perhaps you saw the Auralnauts video from 2014 that removed the score from the final scene: aye, it's played as a gag, but it's also a terrifically useful study in what Williams actually did - he didn't just tell us how to feel (though that is absolutely part of what he did: the binary sunset is another extremely clear example of that principle at work), he was to a large degree telling us what was happening, such that I'd far rather watch the movie with no dialogue than with no music, and not just because a lot more of the dialogue than we generally want to admit is quite terrible.

Might as well run with it, now that it's come up: Lucas's screenplay for Star Wars is absolutely not great. The story is perfectly fine, though clichéd enough that defending its clichés as an archetypal "hero's journey" has been going on since late in 1977. The best elements about the scenario come from the way that Lucas reintroduces the same themes of teenage wistfulness animating his previous film, American Graffiti: Luke Skywalker basically is an amalgamation of that film's Curt Henderson and John Milner, a gearhead (the way he talks about landspeeders is a direct sci-fi analogue for the kind of young man who knows everything about cars) with a yearning sense that he's not living the life he wants, and a constant pressure to take on responsibility without actually being accorded the dignity of adulthood that's the chief source of that yearning. All of that is great stuff. At the level of dialogue, though, the film has more than its share of howlers - the famous one is "But I was going into Tosche Station to pick up some power converters", a line that Hamill delivers in the most petulant whine he could scrape up, and I have almost as little affection for the momentum-shattering swamp of "It's not impossible. I used to bullseye womp rats in my T-16 back home, they're not much bigger than two meters". And even when it's not meeting Harrison Ford's famous denunciation - "You can write this shit, George, but you can't say it" - the film is burdened by flaccid expository dialogue, in which characters fussily remind each other of things they already know; often things they already know that we already know too. It's easy to look to the dreaded prequel trilogy as the point where Lucas began to let his procedural politics infect his storytelling, but there's quite a bit of that present already in Star Wars, too - the scene where the board of the Death Star talks through the recent dissolution of the Imperial Senate is preposterously niggling in this regard.

There is, in fact, quite a lot missing from the human level of Star Wars, not just because the essentialised characters have stupid things to say. Apostasy of apostasies, I don't have terribly favorable feelings towards the three co-leads: Hamill plays Luke as so guileless that he's almost more of an idiot than a rural innocent, and Ford's smug cockiness is intensely one-note; the point where he comes back to save Luke in the Death Star attack feels nothing like the emergence of a secret nobility we knew was there all along, since Ford as done nothing to foreshadow it. And I don't know what the hell Carrie Fisher is up to, with her eerily crisp pronunciations and the turn-on-a-switch way she dials up her emotions: seriously, look at the way she plays her character's shock at learning Alderaan is to be destroyed, and tell me that it's a natural reaction.

On the other hand, the film's supporting cast is much stronger: this will of course happen when Alec Guinness and a horrifyingly sallow Peter Cushing deign to be part of your space opera. Cushing especially: with his hollow cheeks and staring eyes, he's faultlessly threatening as the banal kind of pure evil. Guiness, meanwhile, provided a level of warmth and authority that help paper over how Obi-Wan Kenobi is almost nothing but a backstory dispensing machine (and it's worth always keeping an eye on him: some of his very best work happens in the background of wide shots). And of course, as we move to the less well-established members of the cast, we arrive at the excellent one-two punch of David Prowse's dominating physicality and James Earl Jones's sharp cruelty to create Darth Vader; I am also invariably charmed by the amount of personality Peter Mayhew is able to force through his body language under all that fur as Chewbacca.

Good writing or not, the film has a certain something that makes it entirely easy to understand why people went so absolutely nuts for it: big, bold claims about good and evil with characters who immediately slot into one side or the other based just on how they look (other than Han, the only remotely complex figure in the movie - no accident that he's wearing black and white). It is an easy film, made easier by the simple writing and the pulverising Williams score telling us exactly what to think.

But that does not mean it's artless. The film is great at - not at "world building", which I was about to say. Great at world exploring: in letting a parade of details that receive no comment passing by, whether it's the array of creatures in the cantina, or the droids in the far distance on the Death Star, or the layout of Luke's home, or the fact that a whole movie's worth of colorful flyboys are tossed at us with no introduction. And Lucas, for all of his stilted work as a writer and with actors, had a hell of an eye: the use of depth, of fitting business in the corners of frames where we can observe it or not, and the tensions between characters as a function of how our eye moves between them: all of these things are splendidly on point. Here's a representative shot: the division between Luke and the rest of the frame emphasises his feeling of loneliness (he's just seen his aunt and uncle, burned to death); the unstressed action of C-3PO carrying corpses to the fire morbidly echoes the death we've just scene, the prominence of the landspeeder silently implies the decision to move on to whatever landscapes are to follow.

I will not use the word "sophisticated", but even so, Star Wars is a terrific piece of visual storytelling, and of emotions being produced through image. It is elegant, fluid, graceful, maybe even intuitively cinematic: even the most boring frames (there are a lot of isolated close-ups with too much empty space) are fit by the team of editors into a rhythm that lends them individual weight and impact. The fact that it's in service to such an aggressively pedestrian screenplay is disappointing, of course, and that part of the film's legacy should be loudly bemoaned. Still, even if its status as "like nothing that went before" is grossly overstated, Star Wars is a hell of a drug, the kind of movie that seems almost purposely designed to convince all but the most jaded members of its audience of the expressive power of the medium.

Reviews in this series

Star Wars (Lucas, 1977)

The Empire Strikes Back (Kershner, 1980)

Return of the Jedi (Marquand, 1983)

Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace (Lucas, 1999)

Star Wars: Episode II - Attack of the Clones (Lucas, 2002)

Star Wars: Episode III - Revenge of the Sith (Lucas, 2005)

Star Wars: The Force Awakens (Abrams, 2015)

Star Wars: The Last Jedi (Johnson, 2017)

Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker (Abrams, 2019)

Let us attempt a mental exercise of incredible difficulty: dearest readers, I have faith that you can follow me, though it will be a struggle for us all. Let us disregarded the accumulated knowledge of nearly four decades - of three wholly distinct generations of filmgoers - and of the subsequent history of the film industries of every nation - let us attempt to intellectually locate ourselves in the summer of 1977, and try to imagine what we might think of Star Wars as if it was nothing but a movie. As if it was no more obviously important than the "killer nature" flick Day of the Animals or the Mummad Ali self-starring biopic The Greatest, either one of which we might just as easily have decided to check out on this hotter-than-average weekend of 25 May.

What do we find, if we strip away the accretions of iconic sounds and images, and the foreknoweldge of its many sequels and the almost uncountable number of films copying it in some way, and the awareness that this one film fundamentally changed the way commercial movies would be marketed thereafter? What is this film, in and of itself, and how does it work? These are terrifying questions to consider, but let us please do our best.

Now the reason I think it's most important to force ourselves into this 1977 mindset, beyond the fact that considering the film-as-film really is just so much more pleasurable and revelatory than considering the film-as-icon, is that it allows us to step back from the tediousness of received wisdom about Star Wars and its place in history. As everybody knows, this film and 1975's Jaws are the mean ol' popcorn films that made too much money and ruined the New Hollywood Cinema all by themselves without any other cultural contexts that need to be looked at. But for my part, I think it's much more interesting to consider how those films fit into the filmmaking culture of their time, rather than how they murdered it, or whatever. I of course admit that one can't make the claim that Star Wars is meaningfully part of the New Hollywood without having a sense of consciously swimming against orthodoxy (it's not obviously New Hollywood in the same way that Jaws is, once you decide to stop hating Jaws for existing), but that doesn't mean that it can't also be kind of true.

For one thing, try as we might want to, it doesn't make sense to forbid George Lucas from his generation of directors, since one of the primary things he brings to Star Wars is the sense of heightened film literacy and especially the awareness of film history that are one of the key aspects of '70s American filmmaking. As I'm sure we're all aware by now, Star Wars is really just a remake of Kurosawa Akira's 1958 jidaigeki adventure The Hidden Fortress, seasoned with elements of the old Flash Gordon serial, but that's in and of itself the dream project of an unapologetic film buff. Besides, it's a perfectly satisfying remake of The Hidden Fortress at that, filtering Kurosawa's Western-leaning but essentially Japanese aesthetic back through the quintessentially American giddiness that Kurosawa was replying to in the first place.

But it goes deeper than just "I went to film school!" influences. It's a fundamentally daft thing to say about a space fantasy with laser swords and wizards, but there's a basis of working class realism that sets Star Wars apart from most of the popcorn films it birthed, including its own sequels. For a huge portion of its first half - and by the way, I assume everyone is okay if I don't even nod to a plot summary, right? It's Star Wars, for chrissakes. So hopefully I can just say "everything before they take off from Mos Eisley, which happens 53 minutes into the 121-minute film", and you don't need more to go on than that. Because that's the point I have in mind when I talk about the first half, which is surprisingly grounded and thoroughly non-mythic.

The relatively low budget afforded to the film by 20th Century Fox (convinced that it was going to flop) necessitated some of that, I am sure. Still, it's striking to have a sense of the Star Wars universe and then go back to see how much of it takes place in some sandy crap corner of nowhere, one that's frankly not very attractive. Star Wars is one of the key films in popularising the "used future" aesthetic that would dominate much of science fiction cinema in the years that followed: everything we see, from the bleached white corridors of the first spaceship to the gunmetal interiors of the Death Star, has a distinctly banged-about utilitarian look, but that's never truer than in the scenes set in the Tatooine backwater where Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) suffers sullenly in the manner of bored teen boys since time immemorial. Nothing in the film looks new: the habitations look like they were just barely carved out of the desert, and the desert immediately set itself to swallowing them back up; the giant sandcrawler that the scavenging Jawas sell their after-market droids from has the definite appearance of being more rust than metal. John Barry's production design is fucking tired, with none of the gleam of pulp sci-fi, only a sense of everything being so shitty that everybody stopped paying attention to how shitty it is, and Gilbert Taylor's grainy cinematography, fully embracing the nature of '70s film stock to make everything look brown, adds a disarming sense of raw realism.

It's the film that famously made everybody finally stop thinking about Watergate and Vietnam; and yet it absolutely subscribes to the worn-out sensibility that blanketed American filmmaking in the wake of those societal schisms. It just does so more at the level of visuals and setting than in its narrative.

All of that being said, let's please not bury the fact that Star Wars is still a huge crowdpleaser, and it's quite easy to understand why audiences in '77 took it that way. It is a triumph of spectacular cinema, quite literally from the first shot after the expository crawl ends: the shot of an Imperial Star Destroyer purring angrily over our heads as it moves forward in all its dumbfounding hugeness is one of the great opening scenes in all of popcorn movies. I might even go farther, and say that all of the subsequent history of American blockbuster filmmaking is a response to that Star Destroyer, and the way it is framed to completely dominate our perception, and the way that it uses bleeding-edge visual effects to suck us into the film's reality. That the shot retains its primordial impact even now is almost beyond belief; it must have been a genuinely transformative experience when it was new and unprecedented.

It's worth lingering a bit on how the film works to make its overwhelming sensory impact, because Star Wars represents one of the great achievements in history of assembling a population of terrific craftspeople to build a movie, and Lucas and producer Gary Kurtz proved to be masters at picking the right names, more than at being storytellers, maybe. The film makes its impact through the accumulation of details, like Ben Burtt's sound effects (go ahead, make the lightsaber noise; now remind yourself that once upon a time, somebody had to consciously decide that's what it should sound like), or John Dykstra's astonishing special effects, the most weighty, plausible spaceships that had ever been seen in the movies and the first time since 2001: A Space Odyssey nine years earlier that filmmakers seem to have genuinely cared about sinking so much time into a physically authentic (ignoring the improbable physics) depiction of space. Hell, even the second unit photographers included among their number Carroll Ballard and Tak Fujimoto.

Of course, the most famous of the offscreen collaborators on Star Wars is composer John Williams, and it's no exaggeration to declare him as the individual human most responsible for the film's effect. Star Wars is preposterously laden with music, wonderfully invigorating and endlessly iconic music - I do not know what percentage of the film has some manner of instrumentation underneath the action, but it is surely a very high number. Famously, Williams borrowed the idea of leitmotif, specific cues attached to specific characters or concepts, from the operas of Richard Wagner; it's only a small jump to accuse Star Wars of behaving like an opera itself, where the constant fluctuation of music or even just tuneless sub-musical atmosphere (as in the tractor beam deactivation) guides our response to the film at a level totally divorced from the plot and imagery. Perhaps you saw the Auralnauts video from 2014 that removed the score from the final scene: aye, it's played as a gag, but it's also a terrifically useful study in what Williams actually did - he didn't just tell us how to feel (though that is absolutely part of what he did: the binary sunset is another extremely clear example of that principle at work), he was to a large degree telling us what was happening, such that I'd far rather watch the movie with no dialogue than with no music, and not just because a lot more of the dialogue than we generally want to admit is quite terrible.

Might as well run with it, now that it's come up: Lucas's screenplay for Star Wars is absolutely not great. The story is perfectly fine, though clichéd enough that defending its clichés as an archetypal "hero's journey" has been going on since late in 1977. The best elements about the scenario come from the way that Lucas reintroduces the same themes of teenage wistfulness animating his previous film, American Graffiti: Luke Skywalker basically is an amalgamation of that film's Curt Henderson and John Milner, a gearhead (the way he talks about landspeeders is a direct sci-fi analogue for the kind of young man who knows everything about cars) with a yearning sense that he's not living the life he wants, and a constant pressure to take on responsibility without actually being accorded the dignity of adulthood that's the chief source of that yearning. All of that is great stuff. At the level of dialogue, though, the film has more than its share of howlers - the famous one is "But I was going into Tosche Station to pick up some power converters", a line that Hamill delivers in the most petulant whine he could scrape up, and I have almost as little affection for the momentum-shattering swamp of "It's not impossible. I used to bullseye womp rats in my T-16 back home, they're not much bigger than two meters". And even when it's not meeting Harrison Ford's famous denunciation - "You can write this shit, George, but you can't say it" - the film is burdened by flaccid expository dialogue, in which characters fussily remind each other of things they already know; often things they already know that we already know too. It's easy to look to the dreaded prequel trilogy as the point where Lucas began to let his procedural politics infect his storytelling, but there's quite a bit of that present already in Star Wars, too - the scene where the board of the Death Star talks through the recent dissolution of the Imperial Senate is preposterously niggling in this regard.

There is, in fact, quite a lot missing from the human level of Star Wars, not just because the essentialised characters have stupid things to say. Apostasy of apostasies, I don't have terribly favorable feelings towards the three co-leads: Hamill plays Luke as so guileless that he's almost more of an idiot than a rural innocent, and Ford's smug cockiness is intensely one-note; the point where he comes back to save Luke in the Death Star attack feels nothing like the emergence of a secret nobility we knew was there all along, since Ford as done nothing to foreshadow it. And I don't know what the hell Carrie Fisher is up to, with her eerily crisp pronunciations and the turn-on-a-switch way she dials up her emotions: seriously, look at the way she plays her character's shock at learning Alderaan is to be destroyed, and tell me that it's a natural reaction.

On the other hand, the film's supporting cast is much stronger: this will of course happen when Alec Guinness and a horrifyingly sallow Peter Cushing deign to be part of your space opera. Cushing especially: with his hollow cheeks and staring eyes, he's faultlessly threatening as the banal kind of pure evil. Guiness, meanwhile, provided a level of warmth and authority that help paper over how Obi-Wan Kenobi is almost nothing but a backstory dispensing machine (and it's worth always keeping an eye on him: some of his very best work happens in the background of wide shots). And of course, as we move to the less well-established members of the cast, we arrive at the excellent one-two punch of David Prowse's dominating physicality and James Earl Jones's sharp cruelty to create Darth Vader; I am also invariably charmed by the amount of personality Peter Mayhew is able to force through his body language under all that fur as Chewbacca.

Good writing or not, the film has a certain something that makes it entirely easy to understand why people went so absolutely nuts for it: big, bold claims about good and evil with characters who immediately slot into one side or the other based just on how they look (other than Han, the only remotely complex figure in the movie - no accident that he's wearing black and white). It is an easy film, made easier by the simple writing and the pulverising Williams score telling us exactly what to think.

But that does not mean it's artless. The film is great at - not at "world building", which I was about to say. Great at world exploring: in letting a parade of details that receive no comment passing by, whether it's the array of creatures in the cantina, or the droids in the far distance on the Death Star, or the layout of Luke's home, or the fact that a whole movie's worth of colorful flyboys are tossed at us with no introduction. And Lucas, for all of his stilted work as a writer and with actors, had a hell of an eye: the use of depth, of fitting business in the corners of frames where we can observe it or not, and the tensions between characters as a function of how our eye moves between them: all of these things are splendidly on point. Here's a representative shot: the division between Luke and the rest of the frame emphasises his feeling of loneliness (he's just seen his aunt and uncle, burned to death); the unstressed action of C-3PO carrying corpses to the fire morbidly echoes the death we've just scene, the prominence of the landspeeder silently implies the decision to move on to whatever landscapes are to follow.

I will not use the word "sophisticated", but even so, Star Wars is a terrific piece of visual storytelling, and of emotions being produced through image. It is elegant, fluid, graceful, maybe even intuitively cinematic: even the most boring frames (there are a lot of isolated close-ups with too much empty space) are fit by the team of editors into a rhythm that lends them individual weight and impact. The fact that it's in service to such an aggressively pedestrian screenplay is disappointing, of course, and that part of the film's legacy should be loudly bemoaned. Still, even if its status as "like nothing that went before" is grossly overstated, Star Wars is a hell of a drug, the kind of movie that seems almost purposely designed to convince all but the most jaded members of its audience of the expressive power of the medium.

Reviews in this series

Star Wars (Lucas, 1977)

The Empire Strikes Back (Kershner, 1980)

Return of the Jedi (Marquand, 1983)

Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace (Lucas, 1999)

Star Wars: Episode II - Attack of the Clones (Lucas, 2002)

Star Wars: Episode III - Revenge of the Sith (Lucas, 2005)

Star Wars: The Force Awakens (Abrams, 2015)

Star Wars: The Last Jedi (Johnson, 2017)

Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker (Abrams, 2019)