The frozen North

A review requested by Scott, with thanks for contributing to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

We live in an age when anime - an imprecise term that I try not to use very often, since it doesn't inherently mean anything besides "animation made in Japan", which strikes me as condescending at least, but let's not get bogged down in that kind of aside just yet - I say again, an age in which anime is pretty well understood to be somehow more serious, artistic, and worthy of consideration than other forms of animation. This was not always the case. At its origin, Japanese animation was stuck in the same ghetto as its American and Soviet counterparts: fantasies of one sort of another, generally made for children and generally at a level of quality that wasn't much better than "good enough for children".

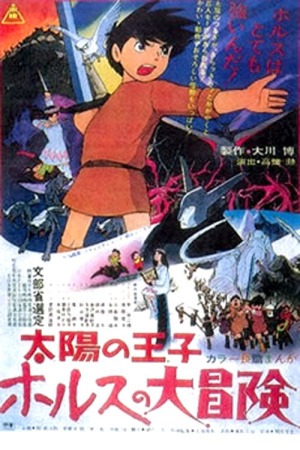

No one film or one studio was responsible for changing that state of affairs in Japan any more than in the Soviet Union (where the shift happened somewhat earlier), but you could do a lot worst in trying to pick the one movie that birthed the modern, artistic animated film for a more discerning audience in that country than a 1968 release that has gone by at least a couple of different English-language titles over the years: I gather that the original Japanese is closest to The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun, but it's much likelier you'll encounter it these days in the anglosphere as Hols, Prince of the Sun, and when it was first shown in the United States, it was thanks to AIP's television division, which provided a rather undemanding dub under the name The Little Norse Prince (and it is this title, and this dub, that you'll encounter if you look for it on any of the major streaming sites - and while I'd want that to be nobody's only exposure to the film, it's absolutely worth it.). Regardless of what the hell we are to call it, it's the movie that is to Japanese animation as that church picnic in Liverpool where John Lennon and Paul McCartney met was to rock and roll: the movie's director was first-timer Takahata Isao, and one of the key animators was Miyazaki Hayao. This was their first collaboration together, and it kicked off an artistic partnership that led to some of the greatest achievements in Japanese animation in the 1970s before resulting in the foundation of Studio Ghibli in the mid-'80s.

It's so easy to over-read that magnificent future into Horus, Prince of the Sun, which isn't just their show - in fact, not even primarily their show, really, since the director of animation, and therefore the man most singularly responsible for the film's visuals, was Otsuka Yasuo (though Miyazaki, along with a few other lead animators, helped Otsuka with the character designs). But this isn't merely an important footnote in Ghibli history: Horus is a splendid film in its own right, one of the most accomplished animated features up to that point in history, from anywhere in the world. It's visually rich like virtually nothing else Japan had produced yet: a clear attempt to meet the standard-bearers at the Disney studios on their own battleground and even surpass them (for it started production in 1965, by which point Disney's aesthetic decline from the lavishness of its 1950s Silver Age had already clearly manifested itself), with a great deal of time and care spent in getting everything perfectly right.

The results speak for themselves. In terms of technique, the film is best-known probably for a tremendous battle between the title character and a giant, murderous pike, which is simply one of the great animated movie monsters ever accomplished, lightning fast, and thick with muscle that twists and jerks with extraordinary fury. It is as great a setpiece as a fantastic adventure could possibly hope for. And every bit as impressive is the character animation - even more impressive, perhaps, because the pike battle demands that you notice it. Whereas the characters, for the most part, are the round little cartoon blobs of any random sample of children's animation in the 1950s or 1960s, but the animators poured so much time and intention into the details of how those soft, ovoid faces would move that the characters are as sophisticated in their range of expression as the more detailed, vividly realistic characters of Disney at its height. It's an extraordinary achievement, maybe even an unprecedented one in its native industry: the soulfulness of the main characters all the way down to the striking reactions of non-characters in comic cutaways are perfectly drafted and animated at a level of fluidity rare in Japanese animation of any generation.

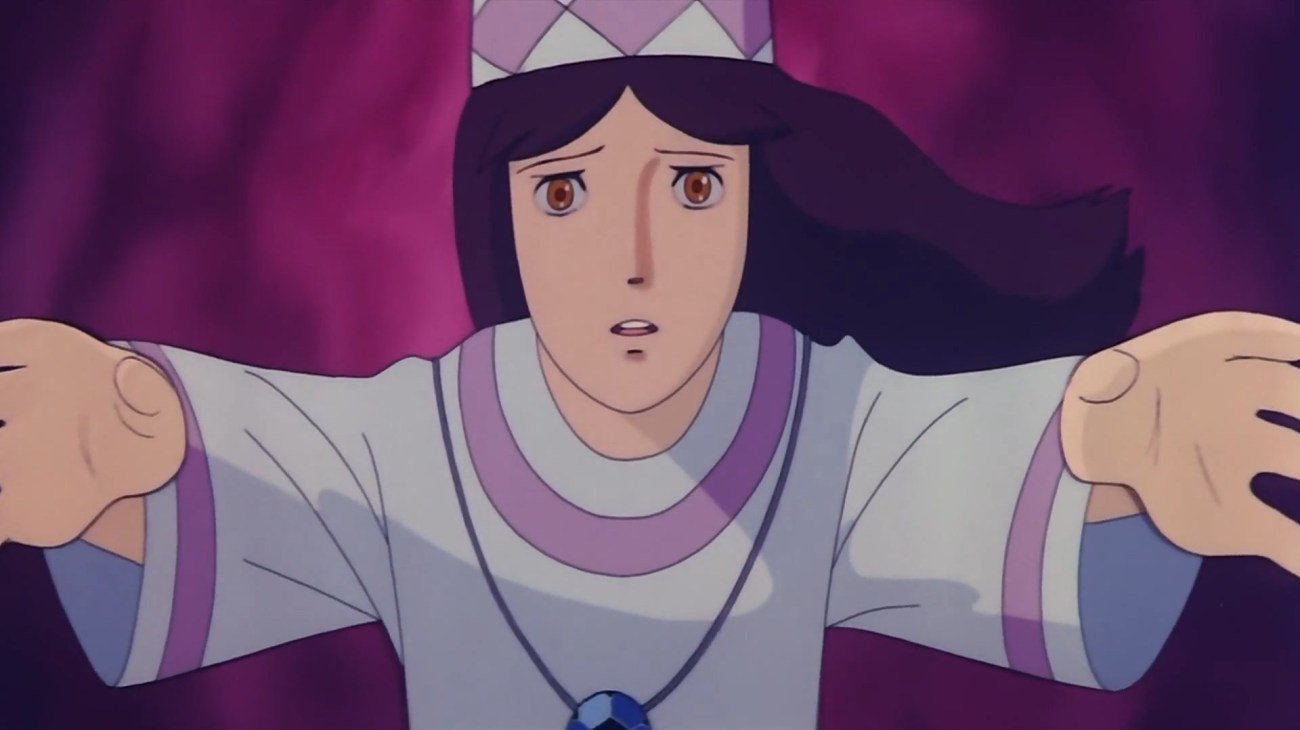

Every bit as impressive, and every bit as foretelling of Ghibli's great achievements to come, is the storytelling. Taken as its basic ingredients, Horus looks like pure fairy tale boilerplate, and in fact the story is ultimately descended from a piece of Ainu folklore. Horus (Okata Hisako) lives out in the wild with his aging father (Yokomori Hisashi), where he one day encounters a rock giant (Yokouchi Tadashi) while escaping from a pack of particularly monstrous wolves. From the giant's shoulder, he plucks an ancient magical sword, thus proving his great fate: he, with his talking bear cub friend Koro (Asai Yukari), shall return to the land of his father's birth to fight a wicked ice demon named Grunwald (Hira Mikijiro). In so doing, he becomes the hero of a small fishing village, and meets a haunted young woman with an ethereal singing voice, Hilda (Ichihara). She is, as it transpires, Grunwald's sister, and initially just a pawn in his attempt to control Horus and destroy the village. But she longs to do good just as much as Horus, only it comes harder to her.

There's nothing about this that's not a kid's movie. But oh, how much more sophisticated and nuanced it is than "kid's movie" implies. The title and first act notwithstanding, this is not just a flouncy adventure about a Chosen One boy with a magic sword. What it turns out to be, first, is a story of how that boy finds himself part of a community, which is depicted mostly by centering on a few key characters, but emphasising the needs of the village as a whole, with the villains those who prefer advancement and power over the greater communal good. Second, it's the story of Hilda, a far more dynamic character than Horus ever comes close to being. Her moral struggle, which dominates the second half of the movie, makes her the first in a grand tradition of young female characters that the future Ghibli artists would take to such great heights in films like My Neighbor Totoro, Spirited Away, and The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. I have not, of course, seen every animated feature made prior to 1968, so I can only go so far as to say that Hilda is the most psychologically complex animated protagonist up to that point that I know of, not that exists, period. But I wouldn't be the slightest bit surprised to learn that such was exactly the case.

In Hilda, Takahata and the story development team (which mostly consisted of Otsuka and the key animators) created a truly groundbreaking animated figure: delicated and conflicted in her visual expressions, deeply intriguing and challenging in her relationship to her sense of morality. It is she, more than anything else, that makes Horus, Prince of the Sun a truly great landmark in grown-up animation, and even as the film feels rather juvenile compared to just about anything that we'd stack it up against nearly a half-century later, Hilda is still as strong as animated protagonists get. Naturally, for this complexity and depth, the film underperformed at the box office; but it was immediately recognised for its greatness and ambition by those who needed to recognise it, and it has managed to acquire the legacy it deserved even if it took some doing to get it there.

We live in an age when anime - an imprecise term that I try not to use very often, since it doesn't inherently mean anything besides "animation made in Japan", which strikes me as condescending at least, but let's not get bogged down in that kind of aside just yet - I say again, an age in which anime is pretty well understood to be somehow more serious, artistic, and worthy of consideration than other forms of animation. This was not always the case. At its origin, Japanese animation was stuck in the same ghetto as its American and Soviet counterparts: fantasies of one sort of another, generally made for children and generally at a level of quality that wasn't much better than "good enough for children".

No one film or one studio was responsible for changing that state of affairs in Japan any more than in the Soviet Union (where the shift happened somewhat earlier), but you could do a lot worst in trying to pick the one movie that birthed the modern, artistic animated film for a more discerning audience in that country than a 1968 release that has gone by at least a couple of different English-language titles over the years: I gather that the original Japanese is closest to The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun, but it's much likelier you'll encounter it these days in the anglosphere as Hols, Prince of the Sun, and when it was first shown in the United States, it was thanks to AIP's television division, which provided a rather undemanding dub under the name The Little Norse Prince (and it is this title, and this dub, that you'll encounter if you look for it on any of the major streaming sites - and while I'd want that to be nobody's only exposure to the film, it's absolutely worth it.). Regardless of what the hell we are to call it, it's the movie that is to Japanese animation as that church picnic in Liverpool where John Lennon and Paul McCartney met was to rock and roll: the movie's director was first-timer Takahata Isao, and one of the key animators was Miyazaki Hayao. This was their first collaboration together, and it kicked off an artistic partnership that led to some of the greatest achievements in Japanese animation in the 1970s before resulting in the foundation of Studio Ghibli in the mid-'80s.

It's so easy to over-read that magnificent future into Horus, Prince of the Sun, which isn't just their show - in fact, not even primarily their show, really, since the director of animation, and therefore the man most singularly responsible for the film's visuals, was Otsuka Yasuo (though Miyazaki, along with a few other lead animators, helped Otsuka with the character designs). But this isn't merely an important footnote in Ghibli history: Horus is a splendid film in its own right, one of the most accomplished animated features up to that point in history, from anywhere in the world. It's visually rich like virtually nothing else Japan had produced yet: a clear attempt to meet the standard-bearers at the Disney studios on their own battleground and even surpass them (for it started production in 1965, by which point Disney's aesthetic decline from the lavishness of its 1950s Silver Age had already clearly manifested itself), with a great deal of time and care spent in getting everything perfectly right.

The results speak for themselves. In terms of technique, the film is best-known probably for a tremendous battle between the title character and a giant, murderous pike, which is simply one of the great animated movie monsters ever accomplished, lightning fast, and thick with muscle that twists and jerks with extraordinary fury. It is as great a setpiece as a fantastic adventure could possibly hope for. And every bit as impressive is the character animation - even more impressive, perhaps, because the pike battle demands that you notice it. Whereas the characters, for the most part, are the round little cartoon blobs of any random sample of children's animation in the 1950s or 1960s, but the animators poured so much time and intention into the details of how those soft, ovoid faces would move that the characters are as sophisticated in their range of expression as the more detailed, vividly realistic characters of Disney at its height. It's an extraordinary achievement, maybe even an unprecedented one in its native industry: the soulfulness of the main characters all the way down to the striking reactions of non-characters in comic cutaways are perfectly drafted and animated at a level of fluidity rare in Japanese animation of any generation.

Every bit as impressive, and every bit as foretelling of Ghibli's great achievements to come, is the storytelling. Taken as its basic ingredients, Horus looks like pure fairy tale boilerplate, and in fact the story is ultimately descended from a piece of Ainu folklore. Horus (Okata Hisako) lives out in the wild with his aging father (Yokomori Hisashi), where he one day encounters a rock giant (Yokouchi Tadashi) while escaping from a pack of particularly monstrous wolves. From the giant's shoulder, he plucks an ancient magical sword, thus proving his great fate: he, with his talking bear cub friend Koro (Asai Yukari), shall return to the land of his father's birth to fight a wicked ice demon named Grunwald (Hira Mikijiro). In so doing, he becomes the hero of a small fishing village, and meets a haunted young woman with an ethereal singing voice, Hilda (Ichihara). She is, as it transpires, Grunwald's sister, and initially just a pawn in his attempt to control Horus and destroy the village. But she longs to do good just as much as Horus, only it comes harder to her.

There's nothing about this that's not a kid's movie. But oh, how much more sophisticated and nuanced it is than "kid's movie" implies. The title and first act notwithstanding, this is not just a flouncy adventure about a Chosen One boy with a magic sword. What it turns out to be, first, is a story of how that boy finds himself part of a community, which is depicted mostly by centering on a few key characters, but emphasising the needs of the village as a whole, with the villains those who prefer advancement and power over the greater communal good. Second, it's the story of Hilda, a far more dynamic character than Horus ever comes close to being. Her moral struggle, which dominates the second half of the movie, makes her the first in a grand tradition of young female characters that the future Ghibli artists would take to such great heights in films like My Neighbor Totoro, Spirited Away, and The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. I have not, of course, seen every animated feature made prior to 1968, so I can only go so far as to say that Hilda is the most psychologically complex animated protagonist up to that point that I know of, not that exists, period. But I wouldn't be the slightest bit surprised to learn that such was exactly the case.

In Hilda, Takahata and the story development team (which mostly consisted of Otsuka and the key animators) created a truly groundbreaking animated figure: delicated and conflicted in her visual expressions, deeply intriguing and challenging in her relationship to her sense of morality. It is she, more than anything else, that makes Horus, Prince of the Sun a truly great landmark in grown-up animation, and even as the film feels rather juvenile compared to just about anything that we'd stack it up against nearly a half-century later, Hilda is still as strong as animated protagonists get. Naturally, for this complexity and depth, the film underperformed at the box office; but it was immediately recognised for its greatness and ambition by those who needed to recognise it, and it has managed to acquire the legacy it deserved even if it took some doing to get it there.

Categories: adventure, animation, japanese cinema, takahata isao