Summer of Blood: 21st Century Horror - This is Halloween

All this happened years ago, and it's long since time to get over it, but it's really and truly baffling that Warner Bros. saw fit to handle Trick 'r Treat so shabbily. Having taken on the feature directorial debut of Bryan Singer's protégé Michael Dougherty (who co-wrote both X2 and Superman Returns for the director), financed by Legendary Pictures and Singer's company Bad Hat Harry, Warner's announced a release date in time for Halloween 2007, only to cancel it at the last minute. That clearly spoke to a lack of faith in the project, though it's hard to say why: the film's December, 2007 premiere at the Butt-Numb-a-Thon festival in Austin was enormously well-received, as was its tour of the horror festival circuit over 2008. The film quickly took on the aspect of a legend, loved by all who knew it and lusted after by those who didn't. And still Warner sat on it. Finally, in October 2009 - two years and one day after its initially-scheduled release date - the company released it straight to DVD.

Not an impressive fate for one of the only obvious instant classics of horror in the first decade of the 21st Century. Trick 'r Treat is not entirely without lumps, but it's a film wherein even the most apparent flaws are so clearly a function of Dougherty's commitment to his muse, a refusal to compromise the personality of the material even slightly, that its flaws simply don't "count". And its strengths are as distinctive and impressive as anything else from its generation of American horror.

This despite having a seemingly insurmountable strike against it from the start: Trick 'r Treat is an anthology film. Anthologies, even horror anthologies, that are uniformly solid do exist, but anthologies with at least one obviously poor segment are much, much more common. Dougherty's script massages things by letting the stories bleed into each other, and he and cinematographer Glen MacPherson do splendid work unifying each of the four stories with an overall sense of thick autumnal night air, while giving each of them enough of a distinct visual style that we can usually tell where we are just at a glance. So it's not as bluntly divided against itself as it might have been, to its benefit.

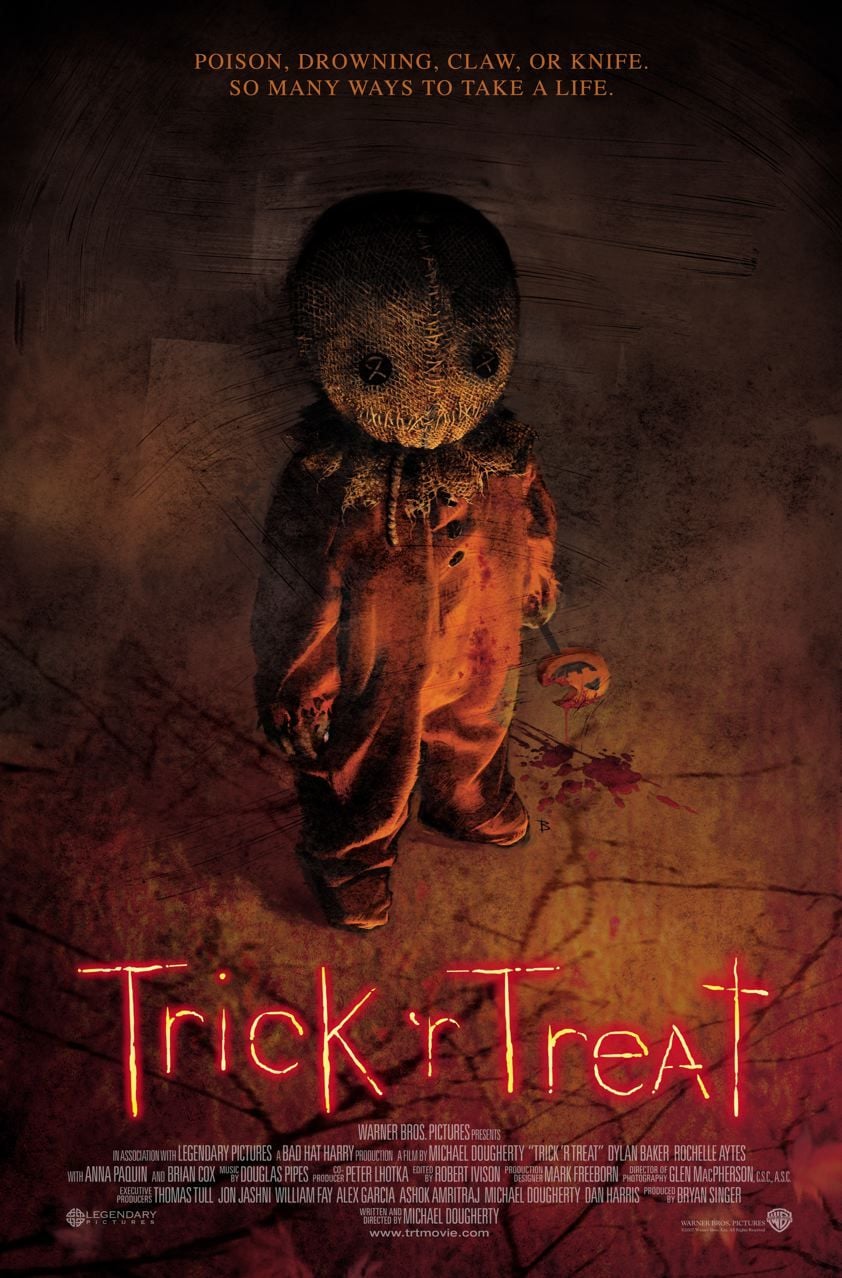

Taken as a whole, the idea of each of the four segments (plus a prologue is basically the same: obey the traditions of Halloween, whatever "tradition" might mean in a given context, even the traditions that Dougherty appears mostly to have invented on the spot. The spirit of Halloween, present to witness and punish those who transgress against these traditions, is a little boy-shaped thing with tattered orange footie pajamas and a burlap mask that vaguely resembles a face; his name is Sam (Quinn Lord), which I take to be short for "Samhain", the Gaelic holiday retrofitted into Halloween. "Samhain" also appears in dialogue, and I am unduly impressed by the fact that it is pronounced correctly ("Sow-win").

The first thing we see is a snippet of a vintage safety video about trick or treating, that cuts to a glowing jack-o'-lantern smile against a pitch black field. It's as direct a reference to the opening credits of the seminal Halloween as I expect that Dougherty wanted to try to get away with, equal parts "I love you and I want to do what you did" and "okay, I can take over now". That jack-o'-lantern, when we see it, belongs to Emma (Leslie Bibb) and Henry (Tahmoh Penikett), a married couple on their way back from a costume party. Emma extinguishes the candle, over Henry's playful objections, and sets herself semi-indifferently to the task of taking down a few of the sheets from the many ghost decorations in the couple's yard, while he gets a porn video set up. Bloody limbs and creepy figures standing at a distance and staring abound, all turning out to be feints; the actual attack on Emma occurs without any set-up at all. It's mechanically perfect, a dance of false scares that distract us from the real scare until it cuts our throat with a jagged pumpkin lollipop.

Between the graceful staging of the scares, the concise, appealing character relationship established in just a few lines between Bibb and Penikett, and the wonderful visuals made by MacPherson's thick and gloomy lighting of the wonderfully evocative neighborhood location (the production design is by Mark Freeborn and the set decoration by Rose Marie McSherry), we've seen everything, in embryonic form, that Trick 'r Treat has in store, somewhere in this wonderfully self-contained anecdote. The rest is all expansion.

The four stories, in the order that they take prominence, center on Steven Wilkins (Dylan Baker), the principal of the local middle school, whose enthusiasm for the nastiest traditions of Halloween leads him to spike the candy he gives out with cyanide, and even this isn't the bleakest thing that happens when bratty kid Charlie (Brett Kelly) shows up; Macy (Britt McKillip), Sara (Isabelle Deluce), Schrader (Jean-Luc Bilodeau), and Chip (Alberto Ghisi), a group of young friends who play a prank on Rhonda (Samm Todd), an autistic girl, by recalling the grisly local story of how a busload of special needs students were driven into a flooded quarry at their parents' behest, and using this as the basis for a mean joke about zombiefied children; Laurie (Anna Paquin), a college-aged virgin whose sister Danielle (Lauren Lee Smith) and friends Maria (Rochelle Aytes) and Janet (Moneca Delain) try to set her up with a guy for their slutty costume party; and Mr. Kreeg (Brian Cox), who hates children and Halloween, and chases away trick or treaters. For this most singular rejection of the spirit of the season, he is particularly targeted by Sam. The mode is very EC Comics: each of the stories ends with a karmic shocker of some kind, and in one case an out-and-out twist (one that is deliciously foreshadowed all over the place; enough to make my least-favorite plotline on first viewing my favorite on a second). And the point is emphatically not anything deeper than a quick jolt of the creeps, exactly as you'd hope to get if you and three buddies were swapping stories around a campfire some Halloween night.

That's easily the film's greatest strength: it is the most Halloweenish Halloween movie of all (something that even Halloween itself, with its charmingly dubious "California summer in Midwestern autumn drag" looks, could never claim). If there is an aspect of Halloween festivities that's not covered by the movie, I can't name it: children play-acting at spooky rituals, adults dressing in filthy costumes, news reporters dutifully spitting out inauthentically cheery boilerplate about some town's overly enthusiastic embrace of extreme kitsch in pursuit of tourism dollars. And the look of the thing! There's no better depiction of the inky blackness of a fall night punctuated by the warm lights of houses and candles on the books, from the opening scene all the way to a climactic jump scare consisting of nothing but Kreeg's terrified discovery that his whole yard has been filled with flickering jack-o'-lanterns, a shot that's as beautiful in its glistening blackness as it is unnerving.

With such a grand creation of a sustained mood, it's little surprise that Trick 'r Treat is top-shelf horror: if not scary, as such, then admirably suffused with the chilliness and mystery of a good ghost story, crossed with the inventive violence of the better slasher films. The reliance on stillness is a gratifying strength, particularly given the frenetic era of horror that the film was made during: the wide shots of Sam standing and observing, repeated throughout the film, are a terrific way of quietly reinforcing a baseline of ominous calm, and most of the tensest moments in the film are also the slowest (this is particularly true in the fog-coated abandoned quarry of the kids' subplot, from its choked-off sound design to the simple little "bye-bye" gesture at its end). But it's no weaker when it opens the throttle: the most shocking gore effects, which I cannot talk about because they qualify as the film's one absolute spoiler, are extremely impressive and particularly unsettling in both conception and execution, especially given how frequently such effects have gone wrong in other movies. Really, as far as the nuts and bolts of horror goes, the film only commits one enormous misstep: it should never let us see underneath Sam's burlap mask, because the blankness of his expression is worth far more than the frankly squirrelly idea for what we eventually see of him.

Is this the film's only actual flaw? Probably not. Not every performance is equally good, particularly in Laurie's segment, where Paquin significantly outclasses all of her scene partners. And it's not one of those horror movies that allow much room for talking up its fascinating character arcs and social commentary: this really is all about the joy and pleasure of sharing scary stories. That's hardly a little thing; in fact, it is much too easy to overlook just how important it is. And to claim that it's the only card Trick 'r Treat has to play is doing no more than accusing the film of being an exemplary addition to a tradition of hair-raising anecdotes older than cinema itself.

Body Count: 9 in the present, plus the 8 children in the flashback to the schoolbus massacre, plus a number devoured in a murderous orgy whose number I cannot satisfactorily arrive at. But I think "not fewer than 23" is a good estimate.

Not an impressive fate for one of the only obvious instant classics of horror in the first decade of the 21st Century. Trick 'r Treat is not entirely without lumps, but it's a film wherein even the most apparent flaws are so clearly a function of Dougherty's commitment to his muse, a refusal to compromise the personality of the material even slightly, that its flaws simply don't "count". And its strengths are as distinctive and impressive as anything else from its generation of American horror.

This despite having a seemingly insurmountable strike against it from the start: Trick 'r Treat is an anthology film. Anthologies, even horror anthologies, that are uniformly solid do exist, but anthologies with at least one obviously poor segment are much, much more common. Dougherty's script massages things by letting the stories bleed into each other, and he and cinematographer Glen MacPherson do splendid work unifying each of the four stories with an overall sense of thick autumnal night air, while giving each of them enough of a distinct visual style that we can usually tell where we are just at a glance. So it's not as bluntly divided against itself as it might have been, to its benefit.

Taken as a whole, the idea of each of the four segments (plus a prologue is basically the same: obey the traditions of Halloween, whatever "tradition" might mean in a given context, even the traditions that Dougherty appears mostly to have invented on the spot. The spirit of Halloween, present to witness and punish those who transgress against these traditions, is a little boy-shaped thing with tattered orange footie pajamas and a burlap mask that vaguely resembles a face; his name is Sam (Quinn Lord), which I take to be short for "Samhain", the Gaelic holiday retrofitted into Halloween. "Samhain" also appears in dialogue, and I am unduly impressed by the fact that it is pronounced correctly ("Sow-win").

The first thing we see is a snippet of a vintage safety video about trick or treating, that cuts to a glowing jack-o'-lantern smile against a pitch black field. It's as direct a reference to the opening credits of the seminal Halloween as I expect that Dougherty wanted to try to get away with, equal parts "I love you and I want to do what you did" and "okay, I can take over now". That jack-o'-lantern, when we see it, belongs to Emma (Leslie Bibb) and Henry (Tahmoh Penikett), a married couple on their way back from a costume party. Emma extinguishes the candle, over Henry's playful objections, and sets herself semi-indifferently to the task of taking down a few of the sheets from the many ghost decorations in the couple's yard, while he gets a porn video set up. Bloody limbs and creepy figures standing at a distance and staring abound, all turning out to be feints; the actual attack on Emma occurs without any set-up at all. It's mechanically perfect, a dance of false scares that distract us from the real scare until it cuts our throat with a jagged pumpkin lollipop.

Between the graceful staging of the scares, the concise, appealing character relationship established in just a few lines between Bibb and Penikett, and the wonderful visuals made by MacPherson's thick and gloomy lighting of the wonderfully evocative neighborhood location (the production design is by Mark Freeborn and the set decoration by Rose Marie McSherry), we've seen everything, in embryonic form, that Trick 'r Treat has in store, somewhere in this wonderfully self-contained anecdote. The rest is all expansion.

The four stories, in the order that they take prominence, center on Steven Wilkins (Dylan Baker), the principal of the local middle school, whose enthusiasm for the nastiest traditions of Halloween leads him to spike the candy he gives out with cyanide, and even this isn't the bleakest thing that happens when bratty kid Charlie (Brett Kelly) shows up; Macy (Britt McKillip), Sara (Isabelle Deluce), Schrader (Jean-Luc Bilodeau), and Chip (Alberto Ghisi), a group of young friends who play a prank on Rhonda (Samm Todd), an autistic girl, by recalling the grisly local story of how a busload of special needs students were driven into a flooded quarry at their parents' behest, and using this as the basis for a mean joke about zombiefied children; Laurie (Anna Paquin), a college-aged virgin whose sister Danielle (Lauren Lee Smith) and friends Maria (Rochelle Aytes) and Janet (Moneca Delain) try to set her up with a guy for their slutty costume party; and Mr. Kreeg (Brian Cox), who hates children and Halloween, and chases away trick or treaters. For this most singular rejection of the spirit of the season, he is particularly targeted by Sam. The mode is very EC Comics: each of the stories ends with a karmic shocker of some kind, and in one case an out-and-out twist (one that is deliciously foreshadowed all over the place; enough to make my least-favorite plotline on first viewing my favorite on a second). And the point is emphatically not anything deeper than a quick jolt of the creeps, exactly as you'd hope to get if you and three buddies were swapping stories around a campfire some Halloween night.

That's easily the film's greatest strength: it is the most Halloweenish Halloween movie of all (something that even Halloween itself, with its charmingly dubious "California summer in Midwestern autumn drag" looks, could never claim). If there is an aspect of Halloween festivities that's not covered by the movie, I can't name it: children play-acting at spooky rituals, adults dressing in filthy costumes, news reporters dutifully spitting out inauthentically cheery boilerplate about some town's overly enthusiastic embrace of extreme kitsch in pursuit of tourism dollars. And the look of the thing! There's no better depiction of the inky blackness of a fall night punctuated by the warm lights of houses and candles on the books, from the opening scene all the way to a climactic jump scare consisting of nothing but Kreeg's terrified discovery that his whole yard has been filled with flickering jack-o'-lanterns, a shot that's as beautiful in its glistening blackness as it is unnerving.

With such a grand creation of a sustained mood, it's little surprise that Trick 'r Treat is top-shelf horror: if not scary, as such, then admirably suffused with the chilliness and mystery of a good ghost story, crossed with the inventive violence of the better slasher films. The reliance on stillness is a gratifying strength, particularly given the frenetic era of horror that the film was made during: the wide shots of Sam standing and observing, repeated throughout the film, are a terrific way of quietly reinforcing a baseline of ominous calm, and most of the tensest moments in the film are also the slowest (this is particularly true in the fog-coated abandoned quarry of the kids' subplot, from its choked-off sound design to the simple little "bye-bye" gesture at its end). But it's no weaker when it opens the throttle: the most shocking gore effects, which I cannot talk about because they qualify as the film's one absolute spoiler, are extremely impressive and particularly unsettling in both conception and execution, especially given how frequently such effects have gone wrong in other movies. Really, as far as the nuts and bolts of horror goes, the film only commits one enormous misstep: it should never let us see underneath Sam's burlap mask, because the blankness of his expression is worth far more than the frankly squirrelly idea for what we eventually see of him.

Is this the film's only actual flaw? Probably not. Not every performance is equally good, particularly in Laurie's segment, where Paquin significantly outclasses all of her scene partners. And it's not one of those horror movies that allow much room for talking up its fascinating character arcs and social commentary: this really is all about the joy and pleasure of sharing scary stories. That's hardly a little thing; in fact, it is much too easy to overlook just how important it is. And to claim that it's the only card Trick 'r Treat has to play is doing no more than accusing the film of being an exemplary addition to a tradition of hair-raising anecdotes older than cinema itself.

Body Count: 9 in the present, plus the 8 children in the flashback to the schoolbus massacre, plus a number devoured in a murderous orgy whose number I cannot satisfactorily arrive at. But I think "not fewer than 23" is a good estimate.

Categories: anthology films, gorgeous cinematography, horror, summer of blood